|

THE COUNTRY OF THE LOCHS

Galloway

Names.

THE Scot has the primitive instinct of nomenclature. When

his name does not begin with" Mac," or end in "son," he is generally a

Wright, a Herd, a Shepherd, a Crock Gallowav Herd, a Smith, a Black, a

Brown, a Grey, or a Reid. His houses, when not name Imaginatively but

obscurely in the aboriginal Gaelic, are Blinkbonnies, Huss-o'-Bields,

Hermitages, Glowerower-'ems, and Cuddlecozies. Beyond the Dungeon o' Buchan,

the Black Craig o' Dec looks to the three Cairnsmores, and the most

northerly of these passes on the regard to the Hill o' the Windy Standard.

These are picturesque compounds, mostly of Saxon speech; the others, that

is, nine out of ten place-names in Galloway, arc still more sonorous and

imaginative in Erse.

“Listen I Ben Cairn and Ben Yelleray, Craigronald,

Neldricken, Mulwharchar, and the Rig 0' the Star, Loch Macaterick and Loch

Enoch, Loch Valley and lonely Loch Moan–it is as if the grim primeval

spirits had sat up there, each on his own particular mountain-top, and

bandied polysyllables instead of bombarding each other with granite

boulders.” 1

And in this encounter the country of the lochs does more

than its share. All these last-quoted names are to be found between Loch

Macaterick and the Glen of Trool. And a dozen more, fully as strange, though

not quite so sonorous. occur to me as I write–such as the Jarkness, Loch

Aron, the Breesha, the Snibe, the Spear o' the Merrick, and the Dungeon o'

Buchan.

Lawless-looking names they are, and two hundred years and

more ago they marked the abiding-place of a most lawless folk. So at least

tradition, uniform and authentic, avers. Nor does the account given in "The

Raiders” seem much exaggerated.

“The greater part of these tribes herded together in the

upper hill-country–the No Man's Sheriffdom, on the borders of the three

counties of Kirkcudbright, Wigtoun, and Ayr–were broken men from the Border

clans and septs–wild Eliots, bystart Beatties from the debateable land, or

even outlaw Scots fleeing from the wrath of their own chief, the Warden of

the Marches. With them there were the Macatericks, a sept of cairds (sturdy

rascals) from the wilder parts of North Carrick and the Upper Ward.

“All these outlaw folk used to plunder the men of the

middle hills till the Lesmahago Whigs rose into power, in the high days of

Presbytery before the return of Charles Stewart, the second of the name,

weary fa' him! Then these, being decent God-fearing men, of a dour and lofty

spirit, and all joined very close by the tie of a common religion, and by

the Covenants (National and Solemn League), rose and made an end of the

Macatericks, driving them forth of their country with fire and sword.

“Those who escaped betook themselves to the wilds of the

moorlands, where no writ ran, no law was obc)'ed, and no

1 “Cinderella” p. 329 (James Clarke & Co.)

warrant was good unless countersigned with a musket. In the

dark days of the Killing, this country (which seems fitted to be the great

sanctuary of the persecuted), was more unsafe for them than any part in the

wilds. For this reason that there were always informers there who, for hire,

would bring the troopers on the poor hunted wretches, cowering with their

ragged clothes and tender consciences in moss-hags and among the great rocks

of granite.

"Then in the times which followed, all the land was swiftly

pacified, save only the 'cairds' country–the cairds being the association of

the outlaw clans that had gathered there. It seems strange that, so long as

their depredations were within bounds, no man interfered with their

marauding, so that they took many cattle, and as many sheep as they had need

of. As to their country itself, no man had the lairdship of it, though my

Lords Stewart of Garlies have long claimed some rights over it. For

centuries the whole of it belonged to the country of the Kennedies, and all

the world knows that they were no better than they should be. As for lifting

a drove of cattle from the lowlands, it had been done by every Macaterick

for generations, though generally from Carrick or the Machars, where the

people are less warlike than in Galloway itself."

1

In making the journey to Enoch, fatiguing enough in any

case, the beauty of hill and water is so amazing that the traveller (if he

takes my advice) will see as much as he can, draw, photograph, observe,

and–read all about it in the next copy of “The Raiders" which comes under

his hand.

But, since such is my duty, I will say a word about each of

the lochs in order. First, there are the twin lochs of Glenhead,

picturesque" gowpenfuls" of water hidden among the heather–no more than a

foretaste of what is to come.

High up on the side of Craiglee, too, lies the Dhu Loch, a

kind of weird, oblong, giant's bath, quite near the summit of the

ridge–sullen and black, overhung by grey crags, and deep to the very

edge–altogether one of the most impressive sights

1 “The Raiders," p. 127. (T. Fisher Unwin.)

on all the face of the moorland. It seems a place where a

murder might have been done, and the body disposed of (with a stone or so in

the neuk of a plaid), without the least trouble.

We look down upon Loch Valley from mounds of glacial

moraine huge and thick. The remains of the broken dam can still be made out

at the beginning of the burn–broken through by that outburst which my friend

Mr. MacMillan was witness of–not by that which is described by Mr. Patrick

Heron.

Loch

Valley.

"When we came to the southern side of Loch Valley, whence

the Gairland Bum issues, we saw a strange and surprising sight: There was a

deep trench, the upper part of which had been recently cut through by alley.

The hands of man, for the rubbish lay all about where the spades had been at

work. The ends of a weir across the outlet of the loch were yet to be seen

jutting into the rushing waters. This had evidently been constructed with

considerable care, and certainly with immense labour. But now it was cut

clean through, and we could see where their sappers had first set their

picks; the power of the flood had done the rest. So great had been the force

of the water that the passage was clean cut as with a knife down to the bed

rock. The deep knoll of sand and jingling stones, which lies like a barrier

across the mouth of the loch, had been severed as one cuts sweet-milk

cheese, and the black waters were yet pouring out from under the arch of ice

that spanned the loch as out of a cave in some frozen Tartarus."

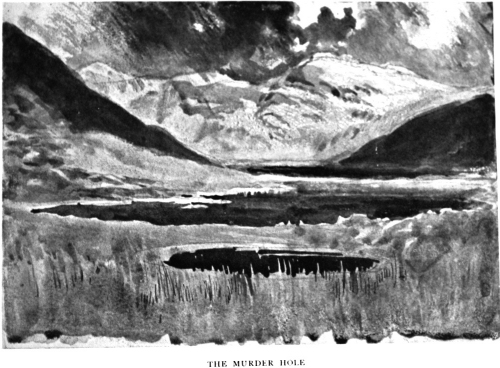

The Murder

Hole.

To this follows a space of crag and rock, and then,

tortuously disposed in a rocky basin, with frowning heights rising about it

on all sides, is Loch Neldricken. We have crossed the Mid-burn near the old

sheep rees, and it is lucky for us if we have managed the transit without

wetting our feet. For the Mid-burn is an unruly stream and often comes

raging down, uncontrollable as the Gairland itself. The sheep-rees, where

for defence the assailants of the raider Faas are said to have sheltered,

are indeed “solidly built of great granite stones like n fortress, based

upon the unshaken ribs of the hills.”

But, strangest of all the strange things about Loch

Neldricken, is that circle of dull, oily-looking water surrounded with tall

reeds towards its north-western shore, which has been named "The Murder

Hole,"

Patrick Heron had experience of it one winter's night,

when, as he says, "I sallied forth, binding my ice-runners of curved iron to

my feet at' the little inlet where the Mid-bum issues-too strong and fierce

ever to freeze, save only at the edges where the frost and spray hung in

fringes, reaching down cold fingers to clasp the rapid waters.

"Away to the left stretched Loch Neldricken, the midmost of

the three lochs of that wild high region–Valley, Neldricken, and topmost

Enoch. I set foot gingerly on the smooth, black ice, with hardly even a

sprinkling of snow upon it. For the winds had swept away the little feathery

fall, and the surface was smooth as glass beneath my feet.

"I was carried swiftly along, and there, not twenty yards

before me, like a hideous black demon's eye looking up at me, lay the

unplumbed depths of the Murder Hole, in which, for the second time, I came

nigh to being my own victim. I remembered the tales told of it. It never

froze; it was never whitened with snow. With open mouth it lay ever waiting,

like an insatiable beast, for its tribute of human life; it never gave up a

body committed to its depths, or broke a murderer's trust.

"The thin ice swayed beneath me, but did not crack–which

was the worse sign, for it was brittle and weakened by the reeds. The lip of

the horrid place seemed to shoot out at me, and the reeds opened to show me

the way. I had let myself down on all fours as I came among the rushes; now

I laid hold of them as I swept along, and so came to a standstill out a

little way from that black verge."1

Somebody (I do not remember who) once remarked to me that

there was more bad weather in "The Raiders" than in any half-dozen books he

had ever read. And going over its pages for the purposes of this writing, I

have been struck

1 “The Raiders," p. 348. (T. Fisher Unwin.)

with the justness of the remark. It is certain that we do get

a good many assorted kinds of evil weather in Galloway, and at such times it

is better to be at home than on the slippery screes between Neldricken and

Craignairny.

Still there is “something naturally prood in the heart of

man," as the wisest and best of herds once remarked to me, “and puir

craiturs that we are, we actually talc' a pleasure in outfacing the

Almichty's ain elements!”

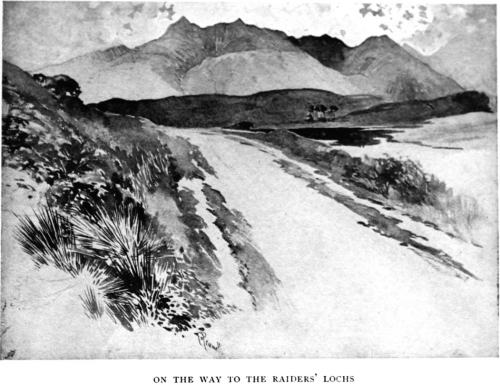

From Neldricken, the Rig of Enoch is seen to hang above us

like a mural fortification. Little Loch Arron we leave away to the left. It

is little more than a mountain tarn. For now all our thoughts are intent on

Enoch–it is at once the most remote of Galloway lochs and the strangest

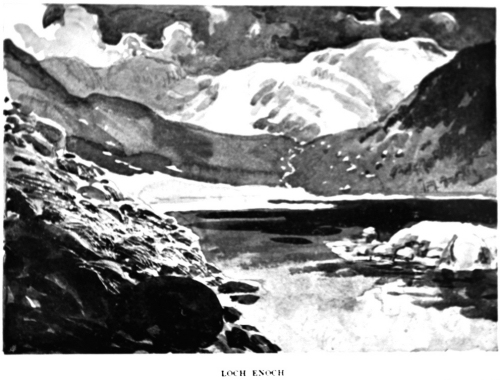

Loch

Enoch.

Yet it is pleasant to be on Enoch-side when the sun

shines–not so marvellous, indeed, as to see its whitening surges through the

driving snow-swirls as the Loch En short fierce days of winter close in.

Still, even so, and in the summer weather, there is ever a sense up there

that somehow heaven is near, and the evil things of the earth remote. "Not

with change of sky changes the mind of man," saith the proverb. But where

Enoch is held up to the firmament as upon a dandling palm of granite rock by

Nature, the Great Mother, the souls of men seem indeed to grow larger and

simpler as they only stand and look.

A few steps to the right along the ridge, and we can gaze

down into the great basin of the Dungeon of Buchan. Here was built the Sheil

of Hector Faa, and it was from this eyrie that his daughter Joyce looked out

for his coming.

“Behind her, almost from her heels, fell away the great

cauldron of the Dungeon of Buchan, wherein the white ground-mists crawled

and swelled–now hiding from sight, and now revealing the three famous

lakelets–the Round Loch, the Long Loch, and the Dry. There were also in the

Dungeon gulf cloud-swirls, that seemed to bubble and circle upwards like the

boiling of a pot. Yet all was still and silent up at the Sheil so that the

faint streak of wood smoke from the fire on the hearth rose straight up the

cliff front, and was lost among the heather and rugged brushwood above. Down

in the cauldron itself, however, there was a veering unequal wind, or,

rather, strife of winds, teasing the mist into wisps white as lambs' wool

and light as blown gossamer."

Indeed, often as I have stood on this spot, I never

remember to have looked into Buchan's Dungeon without seeing something

brewing there. As soon as the sun begins to wester on the finest day of

summer, with the first shadows, the cloud drifts and mist spume begin to

weave a veil over the huge cauldron. The herds are used to call this

phenomenon "the boiling of the pot."

This was what Patrick Heron saw when first he came to Enoch

upon his fateful quest:–

“Presently I found myself on the topmost ledge of all, and

crawling a few paces I looked down upon the desolate waste of Loch Enoch

under the pale light of the stars. It is not possible that I should be able

to tell what I saw, yet I shall try.

The

Dungeon of Buchan.

“I saw a weird wide world, new and strange, not fairly out

of chaos–nor yet approven of God; but rather such a scene as there may be on

the farther side of the moon, which no man hath seen nor can' see. I thought

with some woe and pity on the poor souls condemned, though It were by their

own crimes, to sojourn there. I thought also that, had I been a dweller so

far from ordinances and the cheerful faces of men, it might be that I had

been no better than the outlaw men. And I blamed myself that I had been so

slack and careless in my attendance on religion, promising (for the comfort

of my soul as I lay thus breathing and looking) that when I should be back

in Rathan, May and I should ride each day to church upon a good horse, she

behind me upon a pillion–and the thought put marrow into me. But whether

grace or propinquity was in my mind, who shall say? At any rate I bethought

me that God could not destroy a youth of such excellent intentions.

“But this is what I saw, as clearly as the light

pennitted:1 huge conical hill in front, the Hill of the Star, glimmering

snow-sprinkled, as it rose above the desolations of Loch

Enoch and the depths of Buchan's Dungeon. To the right were the great steeps

of the Merrick, bounding upward to heaven like the lowest steps of Jacob's

ladder. Then Loch Enoch beneath, very black, set in a grey whiteness of

sparse snow and sheeted granite. Last of all I saw in the midst the Island

of Outlaws, and on it, me thought, a glimmering light."

1

It is a far cry to Loch Enoch, but how much farther to Loch

Macaterick and Macaterick's Cove. Sound in wind and limb are those who can

make the journey there and back in a single day. Indeed the cave itself is

not worth going so far to see. One hole in the ground is much like another,

and Macaterick's (at least in its present state), is the meanest of holes

and the humblest of caverns. But it is quite likely that in two hundred

years there may have been some subsidence, and that when Macaterick was a

householder there, the cave of the bold cateran was somewhat more worthy of

his reputation.

As in the days of the Covenant, however, the way to it is

still by the side of a burn which they call the Eglin Lane, a long bare

water, slow and peaty, but with some trout of size in it. Also forth from

the broads of Loch Macaterick there comes another bum with clearer sparkling

water and much sand in the pools. There were trout in both, as one might see

by stealing up to the edge of the brow and looking over quickly. But owing

to the drought there was water only in the pools of Eglin, and often but the

smallest trickle beneath the stones.

“We started just when the heated haze of the afternoon was

clearing with the first early-falling chill of even. The hills were casting

shadows upon each other towards the Dungeon and Loch Enoch, and as we went,

we heard the grey crow crook and the muckle corbie cry ‘Glonk,' somewhere

over by the Slock of the Hooden. They had got a lamb to themselves, or a

dead sheep, belike.

“Then after a long while we found ourselves under the

1 "The Raiders," p. 357. (T. Fisbrr Unwin..)

front of the Dungeon Hill, which is the wildest and most

precipitous in all that country. They say that when it thunders there, all

the lightnings of heaven join together to play upon the rocks of the

Dungeon. And. indeed. it looks like it. For, most of the rocks there are

rent and shattered, as though a giant had broken them and thrown them about

in his play.

“Beneath this wild and rocky place we kept our way, till,

across the rounded head of the Hill of the Star, we caught a glimpse of the

dim country of hag and heather that lay beyond.

“Then we held up the brae that is called the Gadlach, where

is the best road over the burn of Palscaig. and so up into the great wide

valley through which runs the Eglin Lane. So guiding ourselves by our marks,

we held a straight course for the corner of the Back Hill of the Star in

which the hiding place was.

“I give no nearer direction to the famous Cove Macaterick

for the plainest reasons, though it is there to this day, and the herds ken

it well. But who knows how soon the times may grow troublous again, and the

Cove reassert its ancient safety. But all that I will say is, that if you

want to find Cove Macaterick, WiIliam Howatson, the herd of the Merrick, or

douce John Macmillan that dwells at Bongill in the Howe of Trool, can take

you there–that is, if your legs be able to carry you, and you can prove

yourself neither outlaw nor king's soldier. And this word also I say, that

in the process of your long journeying you will find out, that though any

bairn may write a story-book, it takes a man to herd the Merrick.

“So in all good time we came to the place. It is half-way

up a clint of high rocks overlooking Loch Macaterick, and the hillside is

bosky all about with bushes, both birk and self-sown mountain-ash. The mouth

of the cavern is quite hidden in the summer by the leaves, and in the winter

by the mat of interlacing branches and ferns. Above, there is a

diamond-shaped rock, which ever threatens to come down and block

the entrance to the cave. Which indeed it is bound to do some

day.

“Wat and I put aside the tangle and crawled within the

black mouth of the cavern one at a time, till we came to a wider part, for

the whole place is exceedingly narrow and constricted." 1

" Now the cove upon the hillside is not wet and chill as

almost all sea caves are, where the water stands on the floor and drips from

every crevice. But it was at least fairly dry, if not warm, and had been

roughly laid with bog-wood dug from the flowes, not squared at all, but only

filled in with heather tops till the floor was elastic like the many-plied

carpets of Whitehall.

“There was, as I have said, an inner and an outer cave, one

opening out of the other, each apartment being about sixteen feet every way,

but much higher towards the roof. And so it remained till late years, when,

as I hear from the herd of the Shalloch, the rocks of the gairy face have

settled more down upon themselves, and so much contracted the space. But the

cave remains to this day on the Back Hill of the Star over the waters of

Loch Macaterick. And the place is still very lonely. Only the whaups, the

emes, and the mountain sheep cry there, even as they did in our hiding

times."

The which is all very true, and a wonderful wild place is

Loch Macaterick, but the ernes have fled, and the cave has grown yet

smaller, so that I would not desire to mislead the unwary. Still because of

the wildness of the scenery, the strange shores of the loch, and also for

the joy of having been in one of the loneliest places in Scotland, there is

always a peculiar pleasure in looking back on the days we spent in that

wilderness. Given length of days and strength of limb, I mean to go that way

again before I die.

Moreover, one can come back singing to music or his own

composition the Rhyme of the Star Wife, perhaps that very lady who murdered

the herd laddie by putting arsenic

1 “The Men or the Moss-Hags," p. 273 (lsbister & Co.)

in his broth, as the shepherds are keen to relate. 'This is

the stanza :–

“The Slock, Milquharker. and Craignine,

The Breeshie and Craignaw,

Are the five best hills for corklit,

That ever the Star wife saw."

And what corklit is, you find out when you get there!

|