|

THE GLENKENS

AND now we come to the heart of the matter. Every

traveller's road in Galloway leads him at long and last to the Glenkens –and

yet they want a railway, and set poets to ask for it!

Stormy

Music.

But we who are of the older day prefer to think of the

Glenkens as it was in the year of Bothwell Brig, when a certain William

Gordon, of Earlstoun, rode away through these sweet holms and winding paths

south toward the Duchene. Nowhere, to my thinking, is the world so gracious

as between the green woodlands of Earlstoun and the grey Duchrae Craigs. For

(writes the hero) "the pools of the Water of Ken slept, now black, now

silver, beneath us. They were deep set about with the feathers of the

birches, and had the green firs standing bravely like men-at-arms on every

rocky knoll. Then the strath opened out, and we saw Ken flow silver-clear

between the greenest and floweriest banks in the world. The Black Craig of

Dee loomed on our right side as we rode, sulky after the burning of last

year's heather. And the great Kells range sank slowly behind us, ridge

behind ridge of hills whose very names make a storm of music-Millyea,

Milldown, Millfire, Corscrine, and the haunted fastnesses of the Meaull of

Garryhom in the head end of Carsphairn. The reapers were out in the high

fields about Gordonston by daybreak, with their crooked reaping-hooks in

their hands, busily grasping the handfuls of grain and cutting them through

with a pleasant ‘risp' of sound. Cocks crowed early that morning, for they

knew it was going to be a day of fervent heat. It would be as well,

therefore, to have the pursuit of slippery worm and rampant caterpillar over

betimes in the dawning. Then each chanticleer could stand in the shade and

scratch himself applausively with alternate foot all the hot noontide, while

the wives clucked and nestled in the dusty holes along the banks,

interchanging intimate reflections upon the moral character of the giddier

and more skittish young pullets of the farmyard."

Furthermore, I have another reason for remembering the

Glenkens. It was a favourite cycling route of Sweetheart's and mine–in the

good years when cats were kittens, and dogs were puppies, and sheep were

lambs, and Sweethearts had not yet grown up!

"We skimmed under the imminent side of the Bennan Hill, now

purple and golden-brown with the heather and the dying bracken. On our

right, by the lochside of Ken, we passed the little cottage which thirty

years ago was known to all in the neighbourhood as Snuffy Point, from an

occupant who was said to use so much snuff that the lake was coloured for

half a mile round of a deep brown tint whenever he sneezed. A little farther

on is a deep tunnel of green leaves, down which we looked. It leads to

Kenmure Castle. Sweetheart and I always stop just here to dream. It seems as

if we could stretch our arms and float down into the wavering infinitude of

stirring leaves.

"In another minute we had come to the summit of the hill,

and were sliding smoothly down the long, cleanly-kept street of New

Galloway. Not a cur barked in our track–a fact so very remarkable that

Sweetheart asked why.

“' Because New Galloway is a royal burgh,' I said for a

complete answer.

“We passed the entrance to that fascinating Clattering-shaws

road, which leads through the wildest scenery that can be reached by wheels

in the south of Scotland. Soon we were steering northward along the green

holms of the Ken, and, as we looked to the west, the sun was beginning to

sit low on the horizon." 1

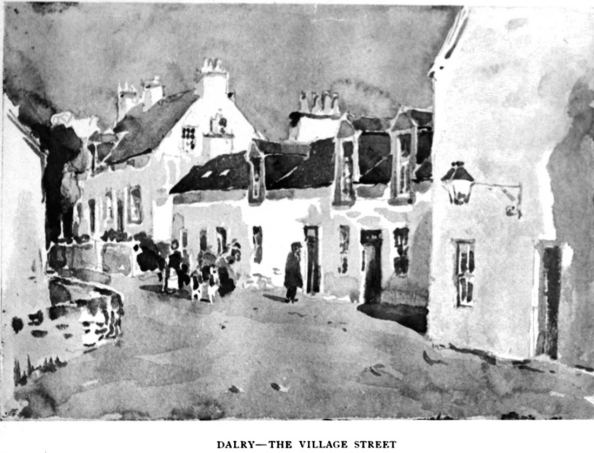

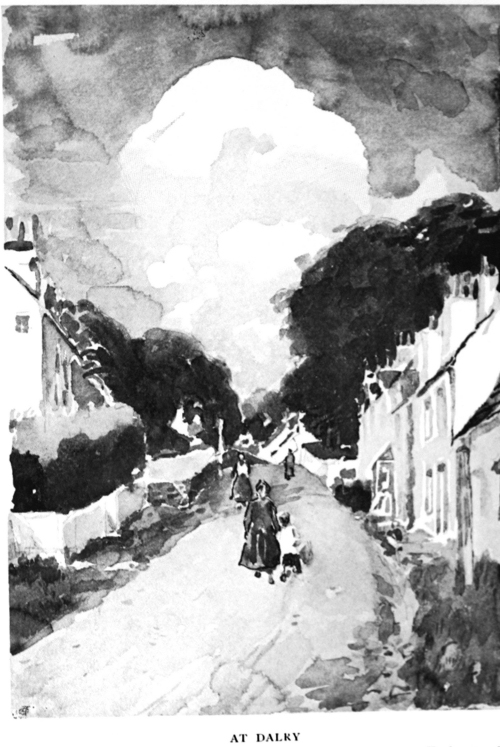

One may spend, as I have done, many hospitable months in

Dairy, housed somewhere in the bright smiling village clambering up its long

slope, or, better still, provided for in the comfortable Lochinvar Hotel. It

is a fine centre for excursions–yet better as a starting-place for the

hill-climber, the botanist, the photographer. There is interest on every

side–the strange, sweet solitudes of the Garpel and Jean's Waa's; the wide

moorland expanse of Lochinvar Loch, Knockman lying far up, lost among the

hills–and, best of all, the old Castle of Earlstoun, the home of Sir

Alexander Gordon, the famous “Bull of Earlstoun," of his scarcely less

famous wife, with her "Contendings " and" Witnessings," and the house, too,

from which came forth Mary, the wife of John MacMillan, "the Cameronian

Apostle," and the first minister of the United Societies.2

There is a beautiful walk from Allangibbon Bridge to the

ruins of Earlstoun, along the waterside, which is quite as lovely to-day as

when John MacMillan traversed it on his way to cast out the devils that had

taken possession of the breast of Alexander Gordon.

"I passed,” he says, “by the little clachan of St. John's

Town of Dairy, leaving it stretching away up the brae-face on my right hand.

A little way beyond the kirk I struck into

1 “ Sweetheart Travellers," p. 226. (Wells Gardner. Darton, &

Co.)

2 It is necessary to apply to the proprietor of Earlstoun,

Mr. Forbes of Callendar. for permission to visit the historic site. Mr.

Forbes grants such orders readily nod courteously, but during his absence it

is well not to go to the castle ruins unprovided with his pass. as a

protection against the Ignorance or insolence or temporary subordinates.

the fringing woods of Earlstoun, which like an army of

trainbands in Lincoln green, beset the grey tower.

The

Clachan of Dairy.

"I was on the sheltered walk along which I had once before

come with her. The water alternately gloomed and sparkled beneath. The fish

sulked and waved The lazy tails, anchored in the water-swirls below the

falls, their heads steady to the stream as the needle to the pole.

"The green of summer was yet untouched by autumn frosts,

save for a russet hair or two on the outmost plumes of the birks that wept

above the stream." 1

The dismantling of Earlstoun is of quite recent date, and

the cornices and ornaments were still fairly complete about 1867, when I

first visited it. I remember there was water in the well at the time–the

Well by the Gate, from which young William Gordon desired so much to drink,

lying and looking across at the home of his youth, presently a garrison of

the oppressor of the Brethren.

"But more and more the desire for the sweet well water of

the gateway tower came to me as I lay parched with thirst, and more than the

former yearning for home things. It seemed that no wine of sunny France, no

golden juice of Xeres, could ever be one-half so sweet as the water of that

Earlstoun well–' that is beside the gate.'

"I remember saying over and over to myself these words,

which I had often heard my father read as he took the Book. ‘0 that one

would give me to drink of the water of the Well of Bethlehem that is beside

the Gate.' So I rose out of the lair where I was, took off my shoes and

stockings, and went down to the riverside. Ken Water is very low at that

season, and, looking over, I could see the fish lying in the black pools

with their noses up stream, waiting for a spate to run into the shallows of

the bums. I declare that, had my mind not been set on the well-house, I

should have stripped there and then for a plunge after them. But in a trice

I had crossed the river, wading to my middle in the clear, warm pool. I

think

1 “The Standard-Bearer," p. 287. (Methuen.)

it was surely the only time that man ever waded Ken to get a

drink of water." 1

“The House of Earlstoun sits bonny above it’s river side,

and there are few fairer waters in this land than the Ken Water. Also, it

looks its bonniest in the early morning when the dew is on all sides, and a

stillness like the peace of God lies on the place. I do not expect the

Kingdom of Heaven very much to surpass Earlstoun on a Sabbath morning in

June, when the bees are in the roses. And, indeed, I shall be well content

with that."

But it was little of that peace which the Gordons knew

during the times of the Covenant. Calm and dignified William Gordon, the

elder, was slain on the eve of Bothwell Brig, though he had not taken any

part in the conflict.

Alexander and his younger brother were haled from prison to

prison. Jean Hamilton, Alexander's wife, was called upon to Huffer for the

faith that was in her, as we shall see hereafter.

But the popular mind dwells longest upon Sandy–as it does

about the memory of all those physically strong, violent men who are yet,

like Samson, full of human weaknesses.

Most famous of all Sandy's feats was his clearing of the

King's Privy Council for Scotland when the fit of anger took him. It was

appointed that he should be tortured, as was then the way with those who

refused to answer, and, as would be said of an elephant, he went suddenly

must.

Sandy and

the Privy Council.

Then the black wrath of his long imprisonment suddenly

boiling over, Sandy took hold on the great iron bar before him and bent his

strength to it–which, when he was roused, was Iike the strength of Samson.

With one rive he tore it from its fastenings, roaring all the while with

that terrible voice of his, which used to set the cattle wild with fear when

they heard it, and which even affrighted men grown and bearded. “The two men

in masks sprang upon him, but he seized them one in each hand and cuffed and

buffeted them against the wall, till I thought he had splattered their

brains on the stones. Indeed, I looked

1 " The Men of the Moss-Hags,” p. 204. (lsbister & Co.)

to see. But though there was blood enough, there were no

brains to speak of. . .

“Then very hastily some of the Council rose to their feet

to call the guard, but the door had been locked during the meeting, and none

for a moment could open it. It was fearsome to see Sandy. His form seemed to

tower to the ceiling. A yellow foam, like spume of the sea, dropped from his

lips. He roared at the Council with open mouth, and twirled the bar over his

head. With one leap he sprang over the barrier, and at this all the

councillors drew their cloaks about them and rushed pell-mell for the door,

with Sandy thundering at their heels with his iron bar. It was all

wonderfully fine to watch. For Sandy, with more sense than might have been

expected of him, being so raised, lundered them about the broadest of their

cloaks with the bar, till the building was filled with the cries of the

mighty Privy Council of Scotland. I declare I laughed heartily, though under

sentence of death, and felt that, well as I thought I had borne myself,

Sandy the Bull had done a thousand times better.

"Then from several doors the soldiery came rushing in, and

in short space Sandy, after levelling a good file with his gaud of iron, was

overpowered by numbers. Nevertheless, he continued to struggle till they

twined him helpless in coils of rope. In spite of all, it furnished work for

the best part of a company to take him to the Castle, whither, 'for a change

of air,' and to relieve his madness, he was remanded, by order of the

Council when next they met. But there was no more heard of examining Sandy

by torture.

“And it was a tale in the city for many a day how Sandy

Gordon cleared the chamber of the Privy Council." 1

At this time it was that Alexander Gordon's wife was turned

out of house and home, and I have thought it worth while to reprint a letter

telling of her expulsion and her troubles, as well as a more extended

narrative of her husband's adventures. The one is genuinely hers, copied

word for word, the other true in substance and fact, but written in

1 “ The Men of the Moss-Hags," p. 376. (Isbister & Co.)

imitation of Jean Hamilton's style. It will not require any

great critical skill to distinguish the real from the imitation.

"DEAR MISTRESS" (50 it runs),–“ your letter did yield great

satisfaction to me, and now I have good words to tell you. The Lord is doing

great things for me. Colvin and Clavers (Cornel) have put us out of all that

we have, so that we know not where to go.

"I am for the present in a cot-house. Oh, blessed cottage!

As soon as my enemies began to roar against me, so quickly came my kind Lord

to me and did take my part. He made even mine enemies to favour me, and He

gave me kindly welcome to this cottage.

"Well may I say that His yoke is easy and His burden light.

" Dear Mistress Jean, praise God on my behalf, and cause

all that love Him to praise Him on my behalf. I fear that I miscarry under

His kind hand.

“Colvin is reigning here like a prince, getting ‘His Honour'

at every word. But he hath not been rude to me. He gave me leave to take out

all that I had. What matters suffering after alI! But, oh! the sad

fallings-away of some! I cannot give a full account of them.

" I have nothing to write on but a stone by the waterside,

and know not how soon the enemy may be upon me. I entreat you to send me

your advice what to do. The enemy said to me that I should not get to stay

in Galloway gif I went not to their kirk.

“They said I should not even stay in Scotland, {or they

would pursue me to the far end of it, but I should be forced to go to their

church. The persecution is great. There are many families that are going to

leave their houses and go out of the land. Gif you have not sent my former

letter let it not now go, but send this as quickly as you can. I fear our

friends will be much concerned. I have written that Alexander may not

venture to come home. I entreat that you will write that to him and close

mine within yours. I have not backed his. Send me all your news. Remember me

to all friends. I desire to be reminded to them.

“I rest, in haste, your loving friend and servant,

”JEAN HAMILTON."

Now, I declare that this letter made me think better than

ever before of Sandy's wife, for I am not gifted with appropriate and

religious reflections in the writing of letters myself. But very greatly do

I admire the accomplishment Jean Hamilton was in time of peace greatly

closed up within herself; but in the time of extrusion and suffering her

narrow heart expanded. Notwithstanding the strange writing-desk of stone by

the waterside, the letter is well written, but the great number of words

which had been blurred and corrected as to their spelling, reveal the

turmoil and anxiety of the writer. |