|

THE HEART OF GALLOWAY, FOUR GALLOWAY FARMS

I.–THE FARM BY

THE WATERSIDE

THE

DUCHRAE OF BALMAGHIE

I BEGIN this book of set

purpose with that which interests me most–with what set its stamp deepest

upon me, in these bright days when the sun had not long risen, and the feel

of morning was in the blood.

The Farm I know best.

The farm I know best is

also the loveliest for situation. It lies nestled in green holm crofts. The

purple moors ring it half round, north and south. To the eastward pinewoods

once stood ranked and ready like battalions clad in indigo and Lincoln green

against the rising sun–that is, till one fell year when the woodmen swarmed

all along the slopes and the ring of axes was heard everywhere. The earliest

scent I can remember is that of fresh pine chips, among which my mother laid

me while she and her brothers gathered "kindling" among the yet

In the Fir Wood.

unfallen giants. Too young

to walk, I had to be carried picka-back to the wood. But I can remember with

a strange clearness the broad spread of the moor beneath over which we had

come, the warmth of the shawl in which I was wrapped, the dreamy scent of

the newly cut fir-chips in which they had left me nested-above all, I recall

a certain bit of blue sky that looked down at me with so friendly a wink, as

a white racing cloud passed high overhead.

Such is the first

beginning that I remember of that outdoor life, to which ever since my eyes

have kept themselves wide-open. Of indoor things one only is earlier.

The Plum-Coulored Cradle.

It was a warm harvest

day–early September, most likely–all the family out at the oats, following

the slow sweep of the scythe or the crisper crop of the reaping-hook.

Silence in the little kitchen of the Duchrae! Only my grandmother padding

softly about in her list slippers (or hoshens), baking farles of cake on the

"girdle," the round plate of iron described by Froissart. The door and

windows were open, and without there spread that silence in comparison with

which the hush of a kirkyard is almost company–the silence of a Scottish

farmyard in the first burst of harvest.

And I–what was I doing? I

know not, but this I do know–that I came to myself lying under the hood of

an old worm-eaten cradle of a worn plum-colour, staring at my own bare toes

which I had set up on the bar at the cradlefoot!

These two memories,

out-door and in-door, have stood out clear and distinct all my life, and do

so now. Nor could I have been told of them afterwards, for there was nothing

in either which concerns any but myself.

The Loch came after. It

lay beneath, at what seemed a Sabbath day's journey from the house of

Duchrae, down a wonderful loaning, full of infinite marvels. Beyond a little

stile tbere was a group of oak trees, from one of which a swing depended.

There was also a sugar-plum tree, under which I first learned the difference

which exists between meum and tuum, a little brook that rippled across the

road (now, I fear, ignominiously conveyed in a drain-pipe), at which the

horses were watered night and morning, and where I gat myself muddied and

soaking–but afterwards, upon discovery, also well warmed.

Then close by the highway

is an unforgotten little elbow of road. The loaning runs straight up and

down now, but you can still see the bend of the old path and the green

bank–nay, only I know where to look for that–the bank on which my mother sat

and sang me "The Lord's my Shepherd" on Sabbath afternoons.

For of all those who were

a part of these things, only one now remains upon the earth. The rest are

over the hill yonder, in the Balmaghie kirkyard, the sweetest and the

sunniest God's Acre in Scotland, and since such things must needs be,

doubtless a right desirable place for any tired wanderer's resting grave.

Then through the gate–no,

the yett–and you are on the road to New Galloway. But keep straight forward

a little way, and you will find the quaintest and most delicious bridge

across the narrows of Woodhall Loch, just where the Lane of Dee runs down to

feed the Black Water of Dee through a paradise of pebbly shallows and reedy

pools. Still black stretches they are also, all abloom with the loveliest

white water-lilies anchored in lee of beds of blonde meadowsweet and red

willow-herb.

A Heavenly Place for Youth.

Such a heavenly place for a

boy to spend his youth in! The water-meadows, rich with long deep grass that

one could hide in standing erect, bog-myrtle bushes, hazel-nuts, and

brambles big as prize gooseberries and black as–well, as our mouths when we

had done eating them. Woods of tall Scotch firs stood up on one hand, oak

and ash on the other. Out in the wimpling fairway of the Black Lane, the

Hollan Isle lay anchored. Such a place for nuts! You could get back-loads

and back-loads of them to break your teeth upon in the winter forenights.

You could ferry across a raft laden with them. Also, and most likely, you

could fall off the raft yourself and be well-nigh drowned. You might play

hide-and-seek about the Camp, which (though marked "probably Roman" in the

Survey Map) is no Roman camp at all, but instead only the last fortification

of the Levellers in Galloway–those brave but benighted cottiers and crofters

who rose in belated rebellion because the lairds shut them out from their

poor moorland pasturages and peat-mosses.

The Levellers.

Their story is told in

that more recent supplement to "The Raiders" entitled "The Dark 0' the

Moon."1 There the record of their deliberations and exploits is

in the main truthfully enough given, and the fact is undoubted that they

finished their course within their entrenched camp upon the Duchrae bank,

defying the king's troops with their home-made pikes and rusty old

Covenanting swords.

"There is a ford (says

this chronicle) over the Lane of Grennoch, near where the clear brown stream

detaches itself from the narrows of the loch, and a full mile before it

unites its slow-moving lily-fringed stream with the Black Water 0' Dee

rushing down from its granite moorlands."

The Lane of Grennoch

seemed to that comfortable English drover, Mr. Job Brown, like a bit of

Warwickshire let into the moory boggish desolations of Galloway. But even as

he lifted his eyes from the lily-pools where the broad leaves were already

browning and turning up at the edges, lo! there, above him, peeping through

the russet heather of a Scottish October, was a boulder of the native rock

of the province, lichened and water-worn, of which the poet sings–

“See yonder on tbe hillside

scaur,

Up amang the heather near

and far,

Wha Granny Granite, auld

Granny Granite,

Gimin' wi' her grey teeth."

If the

traveller will be at the pains to cross the Lane of

The "Roman Camp."

Grennoch, or, as it is now

more commonly called, the Duchrae Lane, a couple of hundred yards north of

the bridge, he will find a way past an old cottage, the embowered

pleasure-house of many a boyish dream, out upon the craggy face of the Crae

Hill. Then over the trees and hazel bushes of the Hollan Isle, he will have

(like Captain Austin Tredennis) a view of the entire defences of the

Levellers and of the way by which most of them escaped across the fords of

the Dee Water, before the final assault by the king's forces.

"The situation was

naturally a strong one–that is, if, as was at the time most likely, it had

to be attacked solely by cavalry, or by an irregular force acting without

artillery.

"In front the Grennoch

Lane, still and deep with a bottom of treacherous mud swamps, encircled it

to the north, while behind was a good mile of broken ground, with frequent

marshes and moss-hags. Save where the top of the camp mound was cleared to

admit or the scant brushwood tents of the Levellers, the whole position was

further covered and defended by a perfect jungle of bramble, whin, thorn,

sloe, and hazel, through which paths had been opened in all directions to

the best positions of defence."

Such about the year 1723

was the place where the poor, brave, ignorant cottiers of Galloway made

their last stand against the edict which (doubtless in the interests of

social progress and the new order of things) drove them from their hillside

holdings, their trim patches of cleared land, their scanty rigs of corn high

in lirks of the mountain, or in blind " hopes" still more sheltered from the

blast.

Evictions.

Opposite Glenhead, at the

uppermost end of the Trool valley, you can see when the sun is setting over

western Loch Moan and his rays run level as an ocean floor, the trace of

walled enclosures, the outer rings of farm-steadings, the dyke-ridges that

enclosed the home-crofts, small as pocket-handkerchiefs; and higher still,

ascending the mountain-side, regular as the stripes on corduroy, you can

trace the ancient rigs where the corn once bloomed bonny even in these

wildest and most remote recesses of the hills. All is now passed away and

matter for romance–but it is truth

all the same, and one may

tell it without fear and without favour.

From the Crae Hill,

especially if one continues a little to the south till you reach the summit

cairn above the farmhouse of Nether Crae, you can see many things. For one

thing you are in the heart of the Covenant Country.

The Country of the Covenant.

"He pointed north to where

on Auchencloy Moor the slender shaft of the Martyrs' Monument gleamed white

among the darker heather–south to where on Kirkconnel hillside Grier of Lag

found six living men and left six corpses–west towards Wigton Bay, where the

tide drowned two of the bravest of womankind, tied like dogs to a stake–east

to the kirkyards of Balmaghie and Crossmichael, where under the trees the

martyrs of Scotland lie thick as gowans on the lea."1

Save by general direction

you cannot take in all these by the seeing of the eye from the Crae Hill.

But you are in the midst of them, and the hollows of the hills where the men

died for their "thocht," and the quiet God's Acres where they lie buried,

are as much of the essence of Scotland as the red Bushing of the heather in

autumn and the hill tams and " Dhu Lochs" scattered like dark liquid eyes

over the face of the wilds.

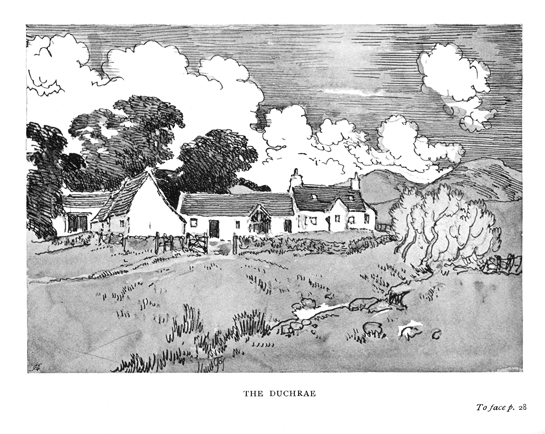

The Duchrae.

Chiefly, however, I love

the Crae Hill because from there you get the best view of the Duchrae, where

for years a certain lonely child played, and about which in after years so

many poor imaginings have worked themselves out. Here lived and loved one

Winsome Charteris–also a certain Maisie Lennox, with many and many another.

By that fireside sat night after night the original of Silver Sand, relating

stories with that shrewd beaconing twinkle in the eye which told of humour

and experience deep as a draw-well and wide as the brown-backed moors over

which he had come.

From these low-lying

craigs in front of the farm buildings, one Kit Kennedy saw the sun raise its

bleared winter-red eye over the snows of Ben Gairn as he hied him homewards

after feeding the sheep. Cleg Kelly turned somersaults by the side of that

crumbling wall, and a score of boys have played out their life games among

the hazels of that tangled waterside plantation which is still to-day the

Duchrae Bank.

There is indeed little

difference about the house since the place was really Craig Ronald–a new

porch to the door, new roofs to the farm buildings, the pleasant front

garden quite abolished. These make the sum of the differences you will find

when you go up the loaning and look for a moment at the white cottage-farm,

where once on a time some of the earth's excellent ones were passing rich on

a good deal less than forty pounds a year. The farm by the waterside is at

its best in harvest, or perhaps–

" About

the Lammas-tide,

When the moor men win their bay."

Then you may chance to

find something like this: "Silence deep as that of yesterday wrapped about

the farmhouse of Craig Ronald. The hens were all down under the lee of the

orchard hedge, chuckling and chunnering low to themselves, and nestling with

their feathers spread balloonwise, while they flirted the hot summer dust

over them. It fell upon their droopy and flaccid combs. Down where the grass

was in shadow a mower was sharpening his blade. The clear metallic sound of

the 'strake' or sharpening strop, covered with pure white Loch Skerrow sand

set in grease, cut through the slumberous hum of the noonday air as the

blade itself cuts through the meadow grass. The bees in the purple flowers

beneath the window boomed a mellow bass, and the grasshoppers made love by

millions in the couch grass, chirring in a thousand fleeting raptures."

Below the Bridge.

Coming down the Crae Hill,

let us return, not by the bridge. but by the front of the deserted cottage.

On your right, as you descend through the pinewood, is a tiny islet, crowded

standing-room for half-a-dozen grown men, but an entire continent (or a boy

to explore in the long days of the blanket-washing, when all the women-folk

of the farm were down there boiling their great pots, rubbing and scrubbing

and rinsing till for twenty yards the brown loch water was tinged with a

strange misty blue. Some years ago, Sweetheart and I found it still covered

as of yore with All-heal and Willow-herb; while the Lane of Duchrae,

beginning its course towards the Black Water, went soughing and murmuring

over the slippery pebbles just as it had been wont to do a good

quarter-century before.

There, straight before us,

at Dan's Ford, is the most practical and delightsome set of stepping-stones

in the world, just tall enough for one to slip off and splash unexpectedly

into the coolness of the water. Or you can sit, as Sweetheart and I used to

do, upon the big central one and eat your lunch, as much isolated as Crusoe

upon his island, the purl of the leaves and the murmur of the ford the only

sounds in that sweet still place. Looking down, you can see at the bottom of

the water long feathery streamers of moss and a little green starry

water-plant (I do not know its name), which I can remember to have tickled

my toes, as I waded there, when as yet neither the dignity nor the

inconvenience of trousers were mine.

Sweetheart's Well.

If the day be hot, and you

would have water of the finest to drink, there is the wayside well a little

farther on the road towards New Galloway Station. Just underneath the bank

you will find it. It has, I fear, been a little cribbed, cabined, and

confined by the official road men, but still there are some cupfuls of

water, cool and delicious, in the deepest shadow. And if you have no

cup–why, take the joined palms of your hands, as Sweetheart and I did in the

Long-Time-Ago.

Going towards New Galloway

Station you keep your face northward, and the road winds between lilied

waters and the steep tangle of the wood. On those fair green braes above the

birches Will Gordon and Maisie Lennox played at Wanderers and King's Men.

And we, like these two, may easily {that is, if we go at the right season}

find the dales and holms pranked with hawthorn and broad gowans, and in the

wood- land hiding-places frail little wild-flowers lurking like hunted

Covenanters or escaping Levellers.

SABBATH AT

THE FARM

Ah, that was another

matter. Still–still with a great stillness, peaceful with an exceeding peace

broke the morning of the Sabbath Day over our Galloway farm. The birds did

not sing the same. The cocks crowed with a clearer, a more worshipful note.

There was a something in the very sunshine as it lay on the grass that was

not of the weekday. A mellower, more restful hush breathed abroad in the

Sabbath air.

The Sabbath Air.

Necessary duties and

services were earlier and more quietly gone about, so that nothing might

interfere with the after solemnities. Yet Sunday was by no means a day of

privation or discouragement for the boy. For not only was his path strewn

with "let ups" from too much gravity by sympathising seniors, but he even

discovered "let ups" for himself, in everything that ran or swam or flew, in

heaven or earth or the waters under.1

Usually when the boy

awoke, the sun had long been up, and already all sounds of labour, generally

so loud, were hushed about the farm. There was a breathless silence, and the

boy knew even in his sleep that it was the Sabbath morning. He arose, and,

unassisted, arrayed himself for the day. Then he stole forth, hoping that he

would get his porridge before the "buik" came on. Through the little end

window he could see his grandfather moving up and down outside, leaning on

his staff–his tall, stooping figure very clear against the background of

oaks. As he went he looked upward, often in self-communion, and sometimes

groaned aloud in the instancy of his unspoken prayer. His brow rose like the

wall of a fortress. A stray white lock on his bare head stirred in the crisp

air. The boy was about to omit his prayers in his eagerness for porridge,

but the sight of his grandfather induced him to change his mind. He knelt

reverently down, and was so found when his mother came in. She stood for a

moment on the threshold, and silently beckoned the good mistress of the

house forward to share the sight. But neither of the women knew how near the

boy's prayers came to being entirely omitted that morning. And what is more,

they would not have believed it had they been informed of it by the angel

Gabriel. For this is the manner of women–the way that mothers are made.

"The Taking of the Buik."

To the breakfast so nearly

unblessed, followed the solemn service of the "Buik"–the "Taking of the

Book," a kind of consecration and thanksgiving in one–a consecration of the

coming week, a thanksgiving for that which had been left behind. The "Buik"

was the key to the life, simple, austere, clear-eyed, forth-looking, yet not

unjoyous, of that Cameronian household–in some wise also the key to Scotland

and to its history for three hundred years.

The family gathered

without spoken summons or stroke of bell. No one was absent, or could be

absent for any purpose whatsoever. The great Bible, clad rough-coated in the

hairy hide of a calf, was brought down from the press and laid at the

table-end. The head of the house sat down before it and bowed himself. In

all the world there was a silence that could be felt. It was at this time

every Sabbath morning that Walter resolved to be a good boy for the entire

week. The psalm was reverently given out, two lines at a time. '

"They in the Lord that

firmly trust,

Shall be like Zion hill."

It was sung to the high

wistful strains of "Coleshill," garnished with endless quavers and

grace-notes. Followed the reading of the Word–according to the portion. The

priest of the family read, as he had sung, "in his ordinary." That is to

say, he read the Bible straight through, morning and evening, even as he

sang the Psalms of David (Paraphrases and mere human hymns being anathema)

from the first to the hundred-and-fiftieth.

To this succeeded the

prayer, when as with one motion all reverently knelt. When the minister came

of an afternoon and "offered up a prayer," that was a regular "service" and

all stood. But when a man prayed in his own house or asked a stranger to

conduct family worship for him, the household knelt. This last was the

highest compliment that could be paid in the waterside farm to any son of

Adam, and to one man only was it ever paid in my recollection–to the

venerable ruling elder of the Cameronian Kirk of Castle - Douglas, Matthew

Craig of Airieland.

The prayer was like the

singing–full of unexpected grace-notes. But there was no liturgy, no

repetition of phrases such as men less spiritual make for themselves. It was

full, as it dropped unconsciously from the speaker's lips, of an unconscious

poetry. It was steeped in mysticism, and a-dream with yearnings and

anticipations, with wistful hopes and painful confessions–all expressed in

the simplest and strongest Biblical words and imagery.

The Kirk-going.

Then the Buik being over,

the red farm cart rattled sedately away down the loaning on its nine-mile

journey, passing on its way Kirks Free and Kirks Established, to deposit its

passengers at the Cameronian Kirk on the Hill, where their ancestors had

listened to the preached Word throughout their generations, ever since the

foundations thereof were laid stone upon his stone.

The red cart was reserved

for the aged and the women. Also sometimes it carried a certain boy, more or

less willing to endure hardness, but, at any rate, not consulted in the

matter. The men folk, uncles long-legged and strapping, with mayhap a friend

or two, cut through by the Water o' Dee, passing Balmaghie Kirk, and so

reached the Kirk on the Hill an hour before the red cart rattled up the

street–so prompt to its time that the dwellers in streets averse from the

town clock set their watches by it.

More often, however, the

boy remained gratefully behind, and after a careful survey of the premises,

he usually went behind the barn to relieve his mind in a rough-and-tumble

with the collie dogs, which, wearing like himself accurately Sunday faces,

had been present at the worship, but now the red cart once out of the way,

were very willing to relapse into such mandane scuffiings, grippings, and

scourings of the countryside as to prove them no right Cameronians of the

blue.

II.–DRUMBRECK UNDERNEATH

THE FLOWE

After the Duchrae, the

Galloway farm I know best is Drumbreck. It is the second of the line of

three white farmsteadings which look towards Laurieston village across the

meadowlands to the south–Quintainespie, Drumbreck, and Bargatton being their

names.

Of Drumbreck my knowledge

belongs to a later time. School holidays were spent here among a generation

almost wholly passed away. The main difference between the Duchrae and

Drumbreck was that at the latter they" kept a man," generally also "a boy,"

and often "a servant lass."

Two Kinsmen.

Two dear and trusty

kinsmen held the farm together–grave, thoughtful, all-reliable men, full of

humour" too and "respecktit" far and near. A right pleasant house to dwell

in was Drumbreck in those days. How I had Shakespeare and Cary's "Dante"

drilled into me by him from whose character (not from whose history) I drew

"The Stickit Minister." I can still see the elder brother with his back on

the sofa deep in politics or sheep-sales–the younger and I meanwhile reading

page and page together of Carlyle, Macaulay, Tennyson, Milton–or, perhaps,

only Knight's "Pictorial History of England"–noting, discussing, arguing,

quarrelling all at once !

"Oh, laddie," I can hear

his cry ring reproachful to this hour, "will ye no believe?

The assurance I D'ye no see

that Macaulay says it? There it is in printers' ink! "

"I dinna care if the Man

in the Moon said it," I would reply to provoke him, " I dinna believe a word

of it! "

A Lonely Boy.

But here, in the stillness

which fell on the farm when the " men" were out at work, I lived a life free

as any bird. Meal-times marked not my life, for owing to household

favouritism in high quarters, dinner, tea, and supper had no definite hours

for me. They were ready in that bounteous house when I dropped in from the

tree-tops–literally–or from among the tussocks and black hags of the moss,

or all adrip from the reedy-weedy lochs which star the great flowe between

Bargatton and Glentoo.

There is a huge slate, now

deeply sunk in beech-wood, on which, when that beech was young, I used to

sit swinging my legs into space and reading every book which I could beg,

borrow or steal–Chambers's "Edinburgh Journal," "Hogg's Instructor," the two

volumes of Chambers's "English Literature "–the last pored over to the point

of illegibility and accounted a most marvellous treasure. These were for

long my chiefest text-books. To which be added, with the ever-present

Shakespeare, a red-bound reprint of the works of a certain great

unappreciated poet, Longfellow by name, soiled with all ignoble use in

primers and recitation books.

The Upper Flowe.

But the natural feature

most characteristic of Drumbreck is the imminence and omnipresence of the

high peat Flowe above it. The arable fields are but islets in an

encompassing peat-moss–hardly won indeed, and yet more hardly kept by

generations of good husbandry. To which be added meadows to the west with

slow black water "lanes," dank and weedy, winding through them, then the

haunt of coot and water-rat, and an admirable practice-ground for the use of

the leaping-pole.

Even the paths which lead

to the little house knoll, with its tall beech-trees and white farm

buildings, are mere threads through the marshes, often overflowed at Espie

Meadow or about Bargatton March.

But high above, imminent

and mysterious, stretched the

chief joy of my life at

Drumbreck–the Flowe, grey with bent and red with heather, by no means

continuous, but, as it were, all In hummocks and tummocks, with green wet

patches between, over which at most times of the year one must leap.

"Puwit!-Pee-wooo! Curly-wee.ee.eel"

So the birds went. Whinnying bleat of snipe, swooping wail of lapwing, the

wild tremolo of the whaup! If I forget thee, Flowe of Drumbreck, may my

right hand forget his cunning. And I loved the moor-birds, though most of

them were deemed birds of ill omen–the whaup perhaps from some fanciful

resemblance of curved beak to the horns of "auld Sawtan, Nick, or Clootie"–and

the peewit, because in that Covenanting country its senseless clamour and

the energy with which it keeps the pot boiling when man invades the domain

it considers its own, often guided the troopers to the hiding-place of the

wanderers for conscience' sake. Anyone who attempts to cross the Flowe of

Drumbreck from the middle of April to the end of July, will easily be

convinced that many of those martyr graves which flower the heather of

Scotland owe their position to the noisy curiosity of this ill-conditioned,

unchancy, yammering bird.

The Avenging of the Martyrs.

It was at least partly in

revenge for this peculiarity that, having discovered four marled eggs laid

small ends together on some bed of bent, I avenged the fallen Covenanters in

a simple and natural fashion. With a paper of salt in one's pocket and a

crust or two of bread, one may go far in the early nesting season and live

daintily all the way.

Above the Flowe of

Drumbreck grey plover, golden plover, and snipe swung and stooped in the

lift–and, I dare say, do so still. On the moor itself whin-chat and

stone-chat "knapped It among the gall-bushes, for all the world like

stone-breakers in their little square niches by the side of the king's

highway.

Straight for the centre of

the moss I made, where, screened from view, at peace with alI men, I drew a

book from my pocket and fell to–the world meantime swinging along as

unregarded as the great white-sailed cloud-galleons aloft. But, here as at

my own birthplace, it was my lot to be a child alone, or (what is the same

thing) a child among grown-ups–a child whose plays are in his head, never

entrusted to another, shared by none, to himself sufficient–so that all

unconsciously he forms the habit of never being less alone than when alone.

The which may be a good

thing or not, according to the child.

Night Adventure.

In later days, with

Drumbreck as a centre, there opened out a new world of night adventure, of

visitations far afield, of practical jests, all the mirth of farm-ingles and

merry meetings under cloud of night. But the time to speak of such things is

not yet, and indeed that is another tale altogether. But if you would know

what it is like–why, you can read the story of the loves of Nance and the

Hempie in a book called "Lads' Love."

III.-THE BIG FARM

AIRIELAND

When I went first to

Airieland it struck me that I had never seen so big a place. The barns were

great as churches. The ploughmen, the herds, and the cotmen formed an army

in themselves. The name of the harvesters was legion. The Big Hoose was a

palace, every room of which I soon transformed into pure romance by

attaching to it some story I had read or dreamed or simply "made up." But my

proper domain was the basement–the kitchen and the parts adjoining. The mere

size and space of these comprised a marvel–the Dairy, the Cheese Room, the

Laundry–all with their names and styles marked in white script across the

doors, even as the pews in the parish church were inscribed with the names

of the farms to which they pertained.

The whisk and scutter of

the rat-armies behind the plaster, and the headlong way in which they used

to run races apparently from the rigging to the cellars of the old house,

struck my soul with a fearful admiration. This used to increase when my aunt

left me to sup my porridge alone in the darkening gloaming, while she went

above stairs to argue with her mistress or tell the lady of the house what

she was to have for supper.

Then during these awful

moments I could see rat after rat stealing across the further wall in awful

pantomime. One, I can remember well, used to sit up and wash its face. But I

thought it was only saying grace before meat, ere it hurled itself at my

throat.

However, as I grew older,

these terrors became no longer affrighting. I grew learned in catapults, and

in time avenged my former fears by the slaughter of more than one rat,

killing necessarily "upon the wing"–not from sporting reasons or pride of

marksmanship, but "because the brutes would not sit still."

The Leddy and her Mistress.

The Leddy of Airieland,

gentle, gracious, kindly above women, was (nominally) my aunt's mistress. My

kinswoman was in service-also nominally. Really was unquestioned both above

stairs or below. So much I gathered even at that early age. Such a

relationship could not exist, or at least hardly, in these later and more

mercenary times.

The Laird of Airieland,

when he passed our way, abode in my grandfather's house as guest with host.

He it was who alone was permitted to "tak' the Buik" in the presence of the

head of the family. Then for a whole long forenoon they would talk the

Fundamentals over together, or settle point by point the minister's last

sermon, shaking grave heads over many a doubtful "application" and

shamefully undeveloped "particular."

"And Jen?" the host would

ask casually after a pause.

He was inquiring for his

daughter.

"Oh, Jen!" her master

would reply with equal carelessness; "Jen's on fit–muckle aboot it, I judge.

At least I heard her telling the mistress she was to get ready the pots for

the berry-jeely boiling the mom!"

There were bells in the

house of Airieland, for the place was a lairds hip. But I never heard one

rung in the way of service. Even when there was "company" the leddy would

come out of the parlour or "room" (meaning dining-room) and call "Jen!" from

the head of the stairs. That was her bell.

The Rlnging of the Bell.

What would have happened

had Jen been rung for I shudder to think. But she never was. That is, except

by me. Prowling one day in a top room' among old lumber, I pulled a cord of

green. Then in the awful silence which followed I heard my aunt's voice far

down in the great empty belly of the house denouncing vengeance. I knew

better than to meet half-way her desire for an immediate interview. So I

ensconced myself in a musty cupboard and waited. The threatenings and

thunders waxed nearer, The door of the garret flew open.

"Na, but–gin I get haud 0'

that loon, I'll break every bane in his peeferin' ill-set body–frichtin'

fowk oot 0' their seeven senses, an' braingin' at a bell that hasna been

poo'ed to my knowledge for thretty year! Come oot 0' that–ye think I dinna

see ye! But I ken whaur ye are. Come oot when I bid ye!"

But I had better judgment

than to stir, being well aware that if Jen had known my whereabouts she

would long ago have had me by the collar, and in the posture of immediate

penance. So I held my breath till she retreated. Then, reaching cautiously

for some old tracts in the cupboard bottom, I came on a precious bundle of

old chapman's ballads and folk-lore taIe–Geordie Buchanan's jests and other

edifying matter among them. By tea-time all-had-been forgotten (if not

forgiven), and I only got my customary cuff in the bygoing, to pay for the

unknown iniquities which Jen was always certain I had been committing.

The Mystery of the Yellow

Room.

There was a room among the

bedrooms in the second floor which had for me the most sinister fascination.

I judge now that I must have dreamed the whole story. But it was dreadfully

real to me then. A murder had been committed there, so I told myself. In

some terrible vision I had been witness of the event. It had been called the

Yellow Room, but they relaid it with blue carpet and put blue paper on the

walls–to hide the blood stains! I remember still taking up some tacks on the

sly and looking under the carpet. The blood was there all right–or, at

least, something that looked like it.

I sounded for trap-doors.

I considered the chances of ropeladders from the window. I even tried to

screw my head up the chimney. But the mystery was a mystery still–and indeed

remains so. Yet I knew clearly enough who it was that had been murdered. She

(it was a she) was the daughter of a former laird of Airieland, and she had

been murdered by her schoolmaster or resident tutor. I did not admire

schoolmasters about that time. I had my reasons. Moreover I was perfectly

certain of the identity of the culprit, and if only I could have brought him

to justice–my, what a time we schoolboys would have had!

The fact that I was

perfectly aware that the murdered lady dwelt in the town of Newmilns, and

continued to occupy herself with beekeeping and the cares of a large family,

in no way detracted from the mysterious nature of the occurrence in the

Yellow Room. At least I had good evidence that a schoolmaster, like

Habakkuk, is capable of anything.

The main difference

between Airieland and my other childhood's homes was, however, that I had

within reach the society of other children of my age. True, within the Big

House itself, I was lonesome as ever–whence, perhaps, proceeded the mystery

of the Yellow Chamber.

But let me but cross over

a stile, dive under an archway, and there, opening out before me, was the

old farm town of Airieland, now turned into a big dairy, and merry all day

long with the sound of children's voices.

Other children, though

hardly of our world, dwelt in the whitewashed row of cathouses away up by

the mill-dam. But we confined ourselves mostly to the wooden lade that

fetched the water to the big mill-wheel at the back of the barn, and to the

shadowy edges of the orchard. Here we climbed trees and sailed boats of bark

and chip all through the long hot summer of 1868.

Beyond the cathouses and

the mill-dam rose a hill of dark heather with the laird's new plantations

fringing every watercourse, and sending scouting parties up among the grey

Silurian rocks.

The Plantation Fire.

Well do I mind me of one

awful Sunday, when for our sins the heather caught fire. We had been

arranging whin tops, bits of stick and heather roots to roast wild-fowl eggs

upon. There was a stiff breeze blowing from the east, and of course the muir-burn

went off at top speed. The water still beads my brow when I think of the

dread despair of that first half-paralysed moment, and the frenzied "Off wi'

your jackets, boys!" with which we sprang to the task of getting it under

control.

My bitterest pang was that

I knew well that it was a judgment upon the sin of Sabbath-breaking. I had

on my Sunday coat–and–I knew what I would get. Nevertheless, to do us

justice, the thought that the laird would know we had burned his plantation

was more than all chastenings, past, present, or to come. At all costs the

fire must be put out. If it reached the plantation, no man of us doubted for

a moment that we would instantly be had out for execution on the gravel in

front of the big house.

Well, the fire was put

out, and our parents and guardians entered duly into judgment with us for

the state of our Sunday clothes. But what cared we? We had set the heather

on fire on Airieland Hill when the wind blew towards the plantations–and

lived to tell the tale. That was glory enough for half-a-dozen eight-year

olds.

But the event had a

distinct moral effect upon me. When I went out to the hill after that upon

the First Day of the week, I was careful to put on my everyday clothes.

The very fact that at

Airieland I was one among other "loons "–none of the highest reputation {and

one tom-boy of a girl among us)–held me aloof from the work of the farm. I

might help to bring home the sixty cows, with hootings and runnings and

mighty "henching" of stones. But nothing more was allowed us.

At home I was used to make

the " bands" for my mother in the harvest field. At Drumbreck I carried the

tea afield to the haymakers between three and four of the afternoon–and

shared the same lying prone upon the nearest hay-cock, two bare legs waving

in the breeze.

The Wonders of Aireland.

But at Airieland we viewed

the reapers from afar off, and listened to the loud g-r-r-r-r of their

machinery, then heard for the first time, with a kind of awe. There

was devilry abroad, we felt,

and the driving of the "reaper" served to gild a certaIn athletic uncle of

mine with a kind of infernal glory.

Beyond the march dyke

again there stretched away the massive slopes of Ben Gairn, the most

universally prominent hill in Galloway, all deep purple heather right to the

summit, from which on clear days we could see the Solway, the white sails of

ships, and certain blowing feathers of smoke, which meant England.

Up to that time I had

never seen any water greater than the narrow loch on the shores of which I

was born. But when I looked down from Ben Gairn upon the sea, I thought

within me that anything less like water I had never seen in my life. It

seemed for all the world like a barn floor, as flat and as dry.

An old well to fall down,

a mill-dam to skip stones upon, a burn to get wet in, an avenue with slaty

shale rubbish to cut your fingers with–these were the other marvels of

Airieland thirty years ago. And above all there was the sweetest and most

gracious of It leddies," who, after her work was done, would often say, "Weel,

laddie, how mony birds' nests hae ye fand the day?" And forthwith, her hand

in mine, and her head nodding pleasantly as its manner was, she would trot

me off to examine the robin's nest in the bank hole, the starling's in the

hole of the beech tree, and the mavis' in the gooseberry bush, as much of a

child as I.

God give her good rest!

For of such (and they are few) is the salt of the earth. She lived to a good

old age, to see her children's children's children growing up about her

knee.

IV.-THE FARM IN

RAIDERLAND

GLENHEAD

OF TROOL

Glenhead in Minigaff.

Glenhead I saw for the

first time in the broad glare of a mid-noon sun. All the valley swam in a

hazy blue mist, and the heat smote down from the white lift as through the

glass of a hothouse.

Yet I have been in

Glenhead during those winter days when for six weeks the· sun does not,

touch its highest chimney-top, so deep the little granite house sits under

the giant hills about It–Bennanbrack, Curly wee, Lamachan, and its own Gairy

shouldering up close behind it.

A Land of Sheep.

Differing from all the

other farms, at Glenhead everything is "black-faced sheep." Their ways,

their care, their difficulties from season to season, their strange

simplicity, their yet stranger outbreaks of unexpected wisdom–the latter

chiefly among the ladies of the flock, those mothers in Israel "snaw-breakers"

by name, who

charge some stubborn

snow-wreath. and so lead out their juniors to safety, and new if scanty

pastures.

Especially in

"lambing-time" all here gives way to "the yowes." The ailments of a mere

human are nothing to those of a ewe" fa'en aval." The mistress herself

establishes hospitals and orphanages, and becomes at once house-surgeon,

hospital dresser, and an entire staff of nurses.

Beneath the house are

winding ribbons of meadow grass following the meanderings of a stream.

Enclosed by a wall behind you will find a "park" or two. A tennis-lawn of

corn waves green in the hollow, a forenoon's work to cut for an ablebodied

man. Beneath remote Clashdaan, away on the shores of Loch Dee, you will find

another triangle of meadow grass, the produce carefully ricked and carried

up beyond ftoodmark. Then behind these the farm rolls back mile after mile.

The number of its acres none knows to a hundred or so, all hills of

sheep-nothing but black-faced sheep, unless you may count a random fox

marauding from Bennanbrack, or a rabbit cocking his white fud Ol'er a brae .

Heather and rock, loch and

lochan, islet and bare granite peak! So it goes on mile after mile, growing

ever more and more lonely and remote, till above Utmost Enoch you look out

upon a land like that where never man comes.

"Nor hath come, since the

making of the world."

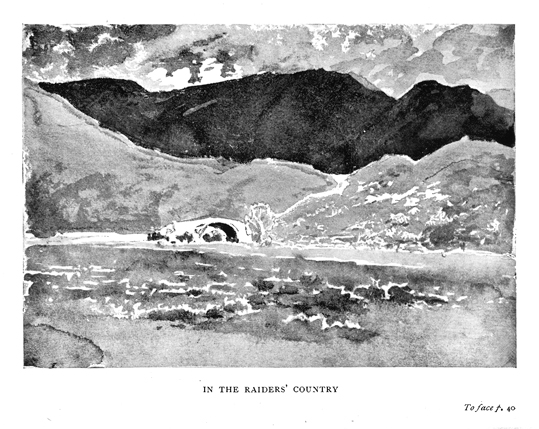

This is the true Raiders'

Country. Yet even from Glenhead you must go six long Scots miles to set your

eyes on Enoch and the Dungeon of Buchan, to look down the great chasm

swimming with vapour, and see the three Lochs of the Dungeon lie like pale

steel puddles far beneath, with the green and treacherous links of the

Cooran winding past them through the morass.

A Far Cry to Loch Enoch.

It is indeed a far cry!

But on the way you will pass Cameron's Grave–not him of Ayr's Moss, the Lion

of the A Far Cry Covenant, but a simpler wayfarer-packman or what not, gone

astray in the storm and found dead by the shepherds in that still and lonely

place.

But I will tell further of

these things when we take pilgrim staff and invade the last Fastnesses of

Hector Faa in the wake of Patrick Heron and May Mischief. It is of the farm

that I would speak; and, in a single word, of the good folk who dwell

therein.

"Dwell,"–aye, there is the

difference. At my other typical farms all is changed. Scarce stands the very

stone and lime where it did.

But at Glenhead these my

dear and worthy friends still hold the door open and cast the eyes of

contented happiness upon the beautiful things about them. May their meal-ark

be ever full to the brim-from their baulks may the bacon flitch depend, and

the ham of yet more delicious mutton. Oaten farles–I think of you and my

teeth water–not cakes of Paradise so toothsome to men coming in sharpset off

the muir. The God of the hills, to which you have so long time lifted your

eyes, be your ward and your rereward. John M'Millan and Mlarion his wife, I,

unforgetting, send you this greeting across mountains and seas and the

remorseless lapse of years. |