|

WOOOHALL LOCH

Barbarlsms.

IT is vain, I fear, to call it Grenoch–as it should be

called. A certain name-changing fiend brought into our Erse and Keltic

Galloway a number of mongrel names, probably some Laird Laurie with a bad

education and a plentiful lack of taste, who, among other iniquities, called

the ancient Clachan-of-Pluck after himself–Laurieston. His mansion·house he

changed from the ancient and honourable "Grenoch," by which name it stands

in Pont's map of (about)

1611 to the commonplace Woodhall. Later the loch had a like

fortune. Loch Grenoch became Woodhall Loch (or in the folk speech of the

parish, Wudha' Loch). Farther afield we have a crop, happily thin sown and

soon finding away of Summerhills, Parkhills, Willowbanks, and such like–of

which that most to be regretted is the merging of the ancient name of the

Duchrae estate in that of the mansion-house of Hensol, a word which has no

historical connection with Galloway, but merely preserves a souvenir (Jf ltv;

f;arly yr)uth f)f a late proprietor.

But Woodhall Loch (after you have become accustomed to the

barbarism) smells as sweet, and its water ripples as freshly as ever did

that of Loch Grenoch–which at least is some comfort.

Setting out northward away from Laurieston, there lie

before you five miles of the most changefully beautiful road in Scottland,

every turn a picture, and in the season every bank wonder of flowers. If the

journey is prolonged to the borough of New Galloway itself, the marvel

becomes only the more marvellous, the changes only the more frequent I have

heard an artist say that a lifetime might be judiciously spent in painting

those ten miles of road without once leaving the highway, and yet the

painter need never repeat his effect.

The fIrst mile to the beginning of the loch itself is

through scenery curiously reminiscent of some parts of central France–the

valley of the Creuse, for instance, George Sand's country –or some of the

lower tributaries of the Tarn. The tall poplars in front of the ruined

smithy, the little bum that trips and ambles for a few hundred paces beside

the traveller and then is lost, hurrying off into the unknown again as if

tired of being overlooked–all these are more French than Scottish.

Myriads of wild flowers throng on every side, at all

seasons of the year when wild flowers can be found in Scotland–indeed many

even in winter.

But as I write I am reminded that remarkable and historical

events happened close to this place where now we pause to look about us,

Greystone.

The house to the right among the trees is Greystone, which

in the days of my youth boasted a genuine ghost–a Lady in White who walked

up and down among the trees, chiefly by moonlight, when I took care not to

be in the neighbourhood. Besides which, the owner and builder of the

beautifully fitted mills, barns, outhouses, ponds–a certain General J –,

much held in awe by all

schoolboys, used to come on Sundays with a gay company and a

team of four horses, and depart (as we boys firmly believed) with a forked

tail hid under his coat, and leaving in his Sabbath-breaking wake a faint

but unmistakable odour of brimstone.

Greystone, or North Quintainespie, was never finished in

the builders lifetime. The exquisite machinery rusted in the mills and

barns. Not a wheel ever turned. Not a sheaf of corn was ever thrashed. The

byres and stables stood locked and silent till a later and better day arose,

when ghosts were laid and Greystone became no more a marvel, but only one

home among many. But at the time the place feared us more than the ministers

sermons, or even the crack of the schoolmasters dog-whip.

Here too, at the beginning of these better days, came a

certain small Sweetheart of mine to do her messages, deliver her orders,

drink her drink of milk, and return in haste to her own. And on that dusty

road a certain “Heart of Gold" was abased–abased in order to be exalted,

tried, and proven, all which is written in the book called “Sweetheart

Travellers," and need not be repeated here.

Farther along is Blates Mill, where (so they tell me) one

Leeb M'Lurg put up her remarkable notice concerning eggs, and held her siege

against her weasel-faced uncle Tim, ere the bull did its ultimate justice

upon him.

Yet a little farther on, its branches bent by the furious

blasts from the loch, stands at an angle of the road, the famous Bogle

Thorn. It seems somehow to have shrunk and grown commonplace since I used to

pass it at a run, with averted eyes, in the winter gloamings on my way home

from school.

The Bogle

Thorn.

Then it had for me the most tragic suggestions. A man, so

they said, had hanged himself upon it at some unknown period. He was to be

seen, evident against the drear dusk, a-swing from the topmost branches,

blowing out in the blast like a pair of trousers hung up to dry, or Dante's

empty souls in the winds of Hades.

Recently, however, I was glad to notice that Sweetheart had

not forgotten the old thrill of fear as we passed it on cycle-back, its

limbs black and spidery against a waning moon.

"In an incautious moment, once upon a time, I had informed

Sweetheart that on the branches of that tree, in years long past, when I

used to trudge past it on foot, there used to be seen little green men,

moping and mowing. So every time we pass that way Sweetheart requires the

story without variations. Not a single fairy must be added or subtracted.

Now, it happens that the road goes uphill at the Bogle Thorn, and to

remember a fairy tale which one has made up the year before last, and at the

same time to drive a tricycle with a great girl of five thereon, is not so

easy as sleeping, So, most unfortunately, I omit the curl of a green

monkey's tail in my recital, which a year ago had made an impression upon a

small girl's accurate memory. And her reproachful accent as she says, 'Oh,

father, you are telling it all different,' carries its own condemnation with

it." 1

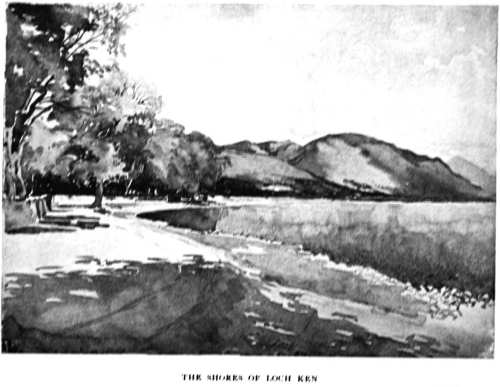

Woodhall Loch is like many another. Half its beauty is in

the seeing eye. Yet not only the educated or the intellectual may see. At

the close of this chapter, I will quote what feelings were excited in the

breast of a country lout by the solemnities of night as viewed from the Crae

Bridge.

But for others who think more of themselves than did Ebie

Farrish the ploughman, the art of admiring nature is chiefly a matter of

habit and leisure. The scytheman, the ploughman, the lowland hind, even the

ordinary farmer, see little of the mysteries of that Nature in the midst of

which they work, dull-eyed as the browsing bullocks.

The man of the high hills is vastly different. There are

few shepherds insensible to the glamour of the mountains and the strange

wild poetry of their occupation. But to the lover, the poet, to the

intelligent townsman all things seem to speak. Ralph Peden, the city

divinity student, lying well content under a thorn-bush above the loch, drew

in that heather-scent which makes the bees tipsy and sets the grass-

1 “Sweetheart Travellers," p. 224. (Wells Gardner, Darton, &

Co.)

hoppers chirring in the long grass by the lochside. It caused

a glamour to come into his head also, in spite of all the philosophies,

I know a bank, where the wild thyme grows–with an

infinitude of other things. You will find it past Blates Mill, past the

Bogle Thorn, just where the loch opens out, and when, standing on tiptoe at

the side of the road, you can see far away, set on the selvage of the

northern moorland, the chimneys of the Duchrae.

Now look down. Between you and the rippling water what a

blaze of colour! You will hardly find such a wealth of flowers anywhere else

in Galloway. The loch, alternate white and blue according as the sunlight or

the breeze catches it, stretches away for all its length of three miles,

cloud and firwood mirroring themselves upon it. If it be June, the first

broad rush of the ling will already be climbing the slopes of the Crae Hill

opposite to you–a pale lavender near the lochside, deepening to crimson on

the dryer slopes where the heath-bells grow shorter and stand thicker

together. At the upper end of the loch, scarcely yet in view, the wimpling

Lane of Duchrae glides away as discreetly from the sleeping lake as if it

were eloping and feared to wake an angry parent. The whole range of hill and

wood and water is drenched in sunlight. Yet everywhere silence clothes it

like a garment, and the wind that blows hither and thither is sweet with the

wild free scent of the moors.

Flowerland.

I cannot even pretend to catalogue the flowers one may hope

to find here–I had almost said, at all times of the year. The outrush of

golden yellow across these braes, gorse and whin, pranked Iike a gay lady,

gave me my first sense of gladness in nature" I used to hurrah all the way

home from school, just because everything–the banks, the knowes, the

roadside, all were of the gladsome yellow. It was my true age of gold, and

even now something throbs in my throat as I think of it. It was the

head-time of all the year–that and the long rush through the spring grass,

when, for the first time, stockings were taken off, and the bare white feet

felt the cool thresh of the close-set herbage, soft and moist and velvety.

It is true that merely to have bought and to have read so

much of “Raiderland"–a book wholly given up to the seeing of the eye, argues

an intelligence in the reader wholly different from that of Ebie Farrish,

the ploughman. But still it will do no harm to remember that, with such

beauties ready to her hand, Nature does work its mysterious work on the

dullest and most animal of human beings.

Ebie has been ”night-raking," as it is expressly called in

Galloway, and now is on his way back to his own proper couch.

“But returning home in the coolness of this night, the

ploughman was, for the time being, purged of the grosser humours which come

naturally to strong, coarse natures, with physical frames ramping with youth

and good feeding. He stood long looking into the Lane water, which glided

beneath the bridge and away down to the Dee without a sound.

“He noted where, on the broad bosom of the loch, the

stillness lay grey and smooth like glimmering steel, with little puffs of

night wind purling across it, and disappearing like breath from a new

knife-blade. He saw also where the smooth satin plain rippled to the first

water-break, as the stream collected itself, deep and black, with the force

of the current behind it, to flow beneath the arch. When Ebie Farrish came

to the bridge he was no more than a material Galloway ploughman, satisfied

with his night's conquests and chewing the cud of their memory.

“He looked over. He saw the stars, which were perfectly

reflected a hundred yards away on the smooth expanse, first waver, then

tremble, and lastly break into a myriad delicate shafts of light, as the

water quickened and gathered. He spat in the water, and thought of trout for

breakfast. But the long roar of the rapids of the Dee came to him over the

hill, and brought a feeling of stillness with it, weird and remote.

Uncertain lights shot hither and thither under the bridge, in strange gleams

and reflections. The ploughman was awed.

He continued to gaze. The stillness closed in upon him. The

aromatic breath of the pines seemed to cool him and remove him from himself.

He had a sense that it was the Sabbath morning, and that he had just washed

his face to go to church. It was the nearest thing to worship he had ever

known. Such moments come to the most material, and are their theology. Far

off a solitary bird whooped and whinnied. It sounded mysterious and unknown,

the cry of a lost soul. Ebie Farrish wondered where he would go to when he

died. He thought this over for a little, and then he concluded that upon the

whole it were better not to dwell on that subject. But the crying on the

lonely hills awed him. It was only a Jack snipe, from whose belated nest an

owl had stolen two eggs. Nevertheless it was Ebie Farrish's good angel. Of a

truth there was that in the world which had not been there before for him.

And it is to his sweetheart's credit, that when Ebie was most impressed by

the stillness and most under the spell of the night, he thought of her. He

was only an ignorant, godless, dull-natured man, who was no more moral than

he could help. But it is both a testimonial and a compliment when such a man

thinks of a woman in his best and most solemn moments.

“A trout leaped in the calm water, and Ebie stopped

thinking of the eternities to remember where he had baited a line. Far off a

cock crew, and the well-known sound warned Ebie that he had better be

drawing near his bed. He raised himself from the copestone of the parapet,

and solemnly tramped his steady way up to the 'onstead' of Craig Ronald,

which took shape before him on the height as he advanced like a low,

grey-bastioned castle." 1

1 “The Lilac-Sunbonnet," p.168. (T. Fisher Unwin.)

|