|

THE KIRK KNOWE OF BALMAGHIE

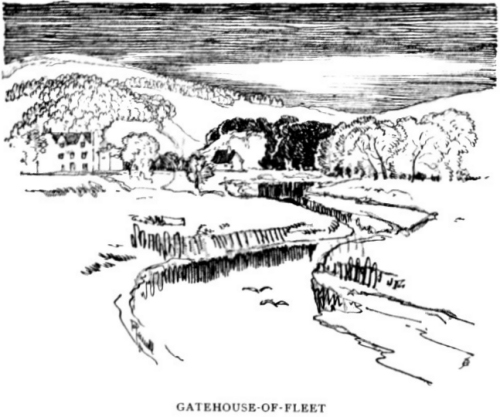

BUT such sights have long been strange to the valley of the

Dee. It is now rich with trees, pasture lands, waving crops, with here and

there, peeping out, the mansions of the great. Cairnsmuir and Ben Gairn

stand out south and north like blue broad-shouldered sentinels. But Castle

Thrieve, tall and stark among its water meadows, though massive as of yore,

is now only four walls of crumbling stone, and the Maid's bridal chamber but

a ruin wherein the clamorous jackdaw may build his nest.

Leaving Glenlochar and Knockcannon on the right there is a

beautiful woodland mile, passing that awkward double turn of road by

Balmaghie High Lodge, the dangers of which suggested the chapter called "The

Green Dook" in "The Banner of Blue." ‘The old house of the M'Ghies of

Balmaghie (often referred to in " Lochinvar" 2) has now no

existence in fact. Its place has been taken by a quite modern mansion-house.

The woodlands have been extended, and there is every reason for believing

that in the seventeenth century the rough, characteristically Galloway

moorland country about Glentoo and the Creochs ran almost to the doors of

the house itself.

Strangely enough, the Kirk of Balmaghie is situated on the

very edge of the parish, most inconveniently for pastoral work, though to

the advantage of the minister's quiet when preparing his sermon. All who

would know more of the truth about Balmaghie Kirk must get Professor Reid's

very excellent little book, "The Kirk above Dee Water." It tells of the

Kirk, its ministers, of the martyrs also, and the many saintly folk who lie

buried in that solitude.

The life of Macmillan, its famous minister, has been for

the first time worthily written by Dr. Reid. "The Cameronian Apostle" cannot

be recommended too often or too highly. It is, in my humble opinion, one of

the most successful pieces of sympathetic biography ever written. And having

made an attempt of the same kind in fiction, I know of what I do speak. I

will return to plunder Dr. Reid's book presently. Meantime I give the words

of Macmillan as they were imagined with regard to his parish.

"Balmaghie was a parish greatly to my mind (so he is

represented as writing). It lies, as every one knows, in the very heart of

Galloway, between the slow, placid, sylvan stretches of the Ken and the

roaring, turbulent mill-race of the Black Water of Dee.

“From a worldly point of view the parish is most desirable;

for though the income in money and grain is not great, nevertheless the

whole amount is equal to the income of most of the smaller lairds in the

neighbourhood. So at last I was settled in my parish, which was indeed a

good and desirable one as times went. The manse had recently been put in

order. It was a

1 Hodder & Stoughton. 2 Methuen.

pleasant stone house, which sat in the bieldy hollow beneath

the Kirk Knowe of Balmaghie. Snug and sheltered it lay, an encampment of

great beeches sheltering it from the northerly blasts, and the green-bosomed

hills looking down upon it with kindly tolerant silence.

The Broad

Dee Water.

“The broad Dee Water floated silently by, murmuring a

little aCter the rains; mostly silently, however-the water lapping against

the reeds and fretting the low

cavernous banks when the wind blew hard, but on the

whole slipping past me with a certain large peace and attentive stateliness.

“The kirk of Crossmichael sits, like that of Balmaghie, on

a little green hill above Dee Water. One house of prayer fronts the other,

and the white kirk yard stones greet each other across the river, telling

one common story of earth to earth. And every Sabbath day across the

sluggish stream two songs of praise go up to heaven in united aspiration

towards one Eternal Father."

"The Sabbath came–a day of infinite stillness, so that from

beside the tombs of the martyr Hallidays in the kirkyard of Balmaghie you

could hear the sheep bleating on the hills of Crossmichael a full mile away,

the sound breaking mellow and fine upon the ear over the broad and azure

river.

"To me it was like the calm of the New Jerusalem. And,

indeed, no place that ever I have seen can be so blessedly quiet as the

bonny kirk-knowe of Balmaghie, mirrored on a windless day in the encircling

stillness of the Water of Dee.

“So, the service being ended for the day, I walked quietly

over to the farm-town of Drumglass. There I found a house well furnished,

oxen and kine knee-deep in the rich grass of water-meadows, hill pastures,

crofts of oat and bear in the hollows about the door, and over all such an

air of bien and hospitable comfort that the place fairly beckoned me to

abide there.” 1

1 “The Standard-Bearer," pp. 102, 141, 217, 231, 318.

(Methuen.)

But the minister of Balmaghie had doubtless more bitter

memories of the manse and the kirk–as when, on the night of his expulsion,

he looked across at the lighted windows of Crossmichael Kirk, in which his

adversaries had assembled to make an end of him.

"Yet more grimly bitter than the day of December the 30th,

fell the night thereof. I wandered by the bank of the river, where the

sedges rustled lonely and dry by the marge, whispering and chuckling to each

other because a forlorn, broken man was passing by. A ‘smurr ' of rain had

begun to fall at the hour of dusk, and the slight ice of the morning and

long since broken up. The water lisped and sobbed as the wind of winter

lapped at the ripples, and the brown peat-brew of the hills took its

sluggish way to the sea.

“Over against me, set on its hill, I saw the lighted

windows of the kirk of Crossmichael. Well I knew what that meant. Mine

enemies were sitting there in conclave. They would not rise till I was no

more minister of the Kirk of Scotland."

Yet such was the temper of the Balmaghie folk that Macmillan

held kirk and manse so long as it pleased him to remain.

From another place I have extracted a morning scene in the

little kirkyard, a description which does not give its ordinary every-day

impression, but rather one of the rarer moods in which the sense of the

Unseen takes hold of us–yet perhaps a picture not less faithful on that

account.

“The little kirk of Balmaghie, is, as I have already

mentioned, set on a hill, and from where I stood its roof and low tower were

clear-cut against the crimson dawn. So red it was that, by contrast, the

very tombstones took on a kind of unearthly green, as the shadowing trees

waved their dead leaves, or, shaking them off, sent them balancing down. So

that with the flaming light above and pale efflorescence beneath, it seemed

as if the spirits of the dead went wavering upwards from their tombs,

gibbering with filmy hands and moaning as they went.

A Mood of Morning.

"There are, indeed, moods of morning far more terrible than

those of the blankest midnight–perhaps premonitory of the shuddering rigours

which shall take us when the pall of the future is removed and That Day

shall dawn upon us-–emote, awful, gIimmering with the infiniteness and

possibilities that are only revealed to us in moments of mortal sickness.

"As I thus watched the dawn and my soul was disturbed

within me, my feet turned of their own accord in the direction of the little

hill-set kirk of Balmaghie. I turned about its eastern side that I might

find the gravestones of the two martyr Hallidays, of which the mistress of

the manse had told me the night before.

"By this time the red colour in the sky had mounted to the

zenith. The sun was transmuting the lower cloud-bars to fantastic islands of

purest gold. The whole pageant of the dawn stood on tiptoe, and then, all at

once calming my harassed and fearful soul, I was a ware of the broad Dee

Water slipping along, a sea of glass mingled with fire, as it seemed,

straight from the throne of God itself."1

To some among us Balmaghie Church appeals more nearly

still. Dear dust lies in that kirkyard, and as the years pass by, for many

of us, more and more of it gathers under the kirk on the hill. The tides of

the world, its compulsions, its needs, and its must be's, lead me up the

loaning but seldom. Indeed I am not often there, save when the beat of the

passing bell calls another to the long quiet rest.

But when the years are over, many or few, and our Galloway

requiem, "Sae he's won awa'," is said of me–that is the bell I should like

rung. And there, in the high corner, I should like to lie, if so the fates

allot it, among the dear and simple folk I knew and loved in youth. Let them

lay me not far from the martyrs, where one can hear the birds crying in the

minister's lilac-bushes, and Dee kissing the river grasses, as he lingers a

little wistfully about the bonny green kirk-knowe of Balmaghie.

1 “The Dark o' the Moon," p. 140. (Macmillan & Co.)

|