|

TWO GALLOWAY SHRINES

I.-RUTHERFORD'S KIRK

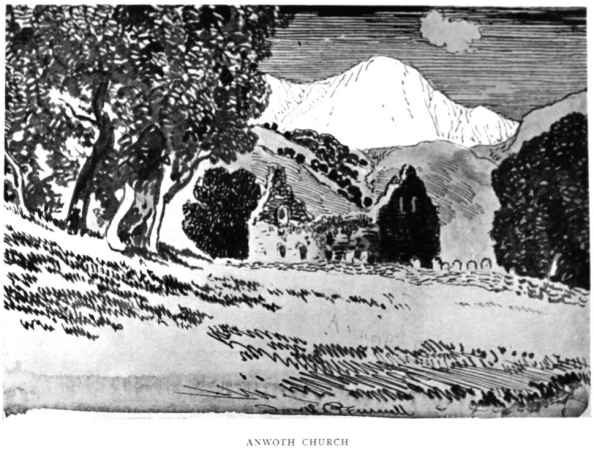

THE howe of Anwoth–Anwoth by the Solway–is dear to many to

whom the name of Samuel Rutherford conveys little. A certain warmth of

temperament and language, even when devoted to temple service, causes his

“Letters" to be misunderstood of some. But no man made his mark deeper on

his time than the “little fair man," whose ministrations are still

remembered in Galloway after well-nigh three hundred years. Even when exiled

to Aberdeen he had more influence in Scotland than the whole bench of

bishops created by King Jamie of the Baggy-Breeks.

But certain words he uttered when dying, have made him more

famous over the world than all the many noble things he did, and the hymn

which enshrines his Passionate and personal aspirings has gone deeper into

the hearts of men and women than Lex Rex or twenty volumes of controversy.

It is well to go to Rutherford's kirk alone, or, as did the

writer of "Sweetheart Travellers," accompanied only by a child:-

"Soon," so is it written in that book, “we glided into the

clean, French-looking village of Gatehouse, where the kindest of baker's

wives insisted on giving us, in addition to rolls and biscuits, ‘some milk

for the bairn.’

“Again we were up and in the saddle. In a moment the

shouting throng fell behind. Barking and racing curs were passed as we

skimmed with swallow flight down the long village street. Then we turned

sharp to the right at the bottom, along the pleasant road which leads to

Anwoth Kirk. Here, in Ruther-

ford's Valley of 'Well Content, the hazy sunshine always

sleeps. Hardly a bird chirped. Silence covered us like a garment. We rode

silently along, stealing through the shadows and gliding through the

sunshine, only our speed making a pleasant stir of air about us in the

midday heats.

“We dismounted, and entered into the ivy-clad walls of

Rutherford's kirk. It is so small that we realised what he was wont to say

when asked to leave it:–

“’ Anwoth is not a large charge, but it is my charge, And

all the people in it have not yet turned their hearts to the Lord! '

“So here we took hands, my Sweetheart and I, and went in,

We were all alone. We stood in God's House, consecrated by the worship of

generations of the wise and loving, under the roof of God's sky. We

uncovered our heads, my little maid standing with wide blue eyes of

reverence on a high flat tombstone, while I told her of Samuel Rutherford,

who carried the innocence of a child's love through a long and stormy life.

Perhaps the little head of sunny curls did not take it all in. What matter?

The instinct of a child's love does not make any mistake, but looks through

scarcely understood words to the true inwardness with unfailing

intuition–it is the Spirit that maketh alive,

“I The Sands of 1i'mt are sinking,' we sang. I can hear

that music yet.

"A child's voice, clear and unfaltering, led. Another, halt

and crippled, falteringly followed. The sunshine filtered down. The big bees

hummed aloft among the leaves. Far off a wood-dove moaned. As the verse went

on, the dove and I fell silent to listen, Only the fresh young voice sang

on, strengthening and growing clearer with each line:–

“Dark, dark hath hem the midnight,

But daysprung is at hand,

And glory-glory dwelleth

In Immanuel’s land!

“As we passed out, a man stood aside from the doorway to

let us go by. His countryman's hat was in his hand. There was a tear on his

cheek also. For he too had heard a cherub praise the Lord in his ancient

House of Prayer."1

It may not be inappropriate to put on record in this place

some of the ancient ways of worship in Galloway of the past–ways that are

now almost extinct, or are driven to their last fastnesses by American

organs and the march of improvement.

The Stated Catechising.

There was, for instance, the Stated Catechising by the

minister. Few now living have submitted to that ordeal from a minister of

the kirk. Yet he who writes has sat out, not one, but several diets of

examination. How he fared is not on record, but it is related that on one

occasion his grandmother prompted him, and was sternly reproved for so

doing. The actual scene was something like this:–

“The family and dependants were all gathered together in

the wide cool kitchen of Drumquhat, for it was the time for the minister's

catechising. The Head of the House sat with his wife beside him. The three

sons–Alec, James, and Rob–sat on straight-backed chairs; Walter near by, his

hand on his grandmother's lap.

1 "Sweetheart Travellers," p. 16. (Wells Gardner, Darton &

Co.)

“Question and answer from the Shorter Catechism passed from

lip to lip, like a well-played game in which no one let the ball drop. It

would have been thought as shameful if the minister had not acquitted

himself at ‘speerin' the questions deftly and instantaneously, as for one of

those who were answering to fail in his replies. When Rob momentarily

mislaid the ‘Reasons Annexed' to the fifth commandment, and his very soul

reeled in the sudden terror that they had gone from him for ever, his father

looked at him as one who should say, ‘Woe is me that I have been the

responsible means of bringing a fool into the world!’ Even his mother gazed

at him wistfully, in a way that was like cold water running down his back,

while the minister said kindly, ‘Take your time, Robert!'

“However, Rob recovered himself gallantly, and reeled off

the Reasons Annexed with vigour. Then he promised, under his breath, a sound

thrashing to his model brother, James, who, having known the Catechism

perfectly from his youth up, had yet refused to give a leading hint to his

brother in his extremity."1

The

Collection.

On Sundays the church collection was not taken up on plates

at the door of the kirk, but the elders gathering the offerings went slowly

and leisurely along the pews, from which the Bibles had been removed. The

plain deal collection-boxes, each at the end of a pole and of an age coeval

with the kirk itself, slid along the book-boards with a gentle equable

noise, as the coppers and the silver severally rattled and dripped into

them. It was the ancient solid members of the Kirk of the Hill who gave

these last, while strangers, dibbled somewhat thickly and obviously among

the true sheep, dropped in the clattering pennies.

“William Kelly, sometime betheral to the Kirk of the Hill,

looked censoriously at the collection when it was emptied out on the table

of the little vestry.

“’ I wonder that man ower at the Kirk 0' Keltonhill canna

1 “Bog-Myrtle and Peat." p. 368: (Sands & Co.)

keep his folk at hame, Their bawbees are like to gie oor

bonny white collection the black jaundice.'

“The first great feature of the day's service was the I

opening

prayer.' It was very long, generally over half-an-hour, and

correspondingly comprehensive. The Boy-that-Was always knew to a dot when

the minister, as it were, turned his team homeward.

“Indeed the whole congregation was good at that, and

hearers began to relax themselves from their standing postures as the

minister's shrill pipe rounded the corner and tacked for the harbour; but

the Boy was always down before them. Once, however, after he had seated

himself he was put to shame by the minister suddenly darting off on a new

excursion, having remembered some other needful supplication which he had

omitted. The Boy never quite regained his confidence in the minister after

that. He had always thought him a good and Christian man, but thereafter he

was not so sure.

“Once, also, when the minister visited the farm of

Drumquhat, the Boy, being caught by his granny in the very act of escaping,

was haled to instant execution with the shine of the soap on his cheeks and

hair. But the minister proved kind, and did not ask for anything more

abstruse than 'Man's Chief End.' He inquired, however, if the boy had ever

seen him before.

“’Ow ay,' came the answer confidently; 'ye're the man that

sat at the back window!'

"This was the position of the manse seat, and at the Fast

Day service the minister usually sat there when a stranger preached. Not the

least of Walter's treasures, now in his library, is a dusky little squat

book called ‘The Peep of Day,' with an inscription on it in Mr. Kay's minute

and beautiful back-hand: ‘To the Boy who Remembered, from the Man at the

Back Window.'

"The minister was grand. In fact, he usually was grand. On

Sunday he preached his two discourses with only the interval of a psalm and

a prayer; and his first sermon was often on the spiritual rights of a

Covenanted kirk, as distinguished from the worldly emoluments of an Erastian

establishment. Nothing is so popular as to prove to people what they already

believe, and that sermon was long remembered among the Cameronians, It redd

up their position so clearly, and settled their precedence with such

finality, that the Boy, hearing how the Frees had done far wrong in not

joining the Cameronians in the year 1843, resolved to have his school-bag

full of good road-metal on the following morning, in order to bring the

Copland boys (who were Frees) to a sense of their position.

“But as the sermon proceeded on its conclusive way, the

bowed ranks of the attentive Hill Folk bent farther and farther forward,

during the lengthy periods of the preacher. And when, at the close of each,

they drew in a long, united breath like the sighing of the wind, and leaned

back in their seats, the Boy's head began to nod over the chapters of First

Samuel, which he had been spelling out.

“David's wars were a great comfort to him during these long

sermons. Gradually he dropped asleep, and wakened occasionally with a start

when his granny nudged him if her husband happened to look his way.

"As the little fellow's mind thus came time and again to

the surface, he heard snatches of fiery oratory concerning the Sanquhar

Declarations and the Covenants, National and Solemn League, till it seemed

to him as though the trump of doom itself would crash before the minister

had finished. And he wished it would! But at last, in sheer desperation,

having slept apparently about a week, he rose with his feet upon the seat,

and in his clear, childish treble he cried, being still dazed with sleep,

‘Will that man no' soon be dune!' "

II.-SHALLOCH-ON-MINNOCH

The second and very different Covenanting sanctuary marks a

later stage of the controversy between the King's ill counsellors and his

Scottish subjects. Shalloch-on-Minnoch lies far afield and will be little

visited. It lies close to the border line which divides Ayrshire from

Galloway. But to aU intents and purposes it holds of Galloway, and you reach

it from Newton-Stewart by driving straight on up the valley, instead of

turning to the right towards Glen Trool and its manifold beauties of loch

and mountain.

"The Societeis.”

Shalloch-on-Minnoch was the most famous of all the

Cameronian meeting-places, not even making an exception of Friarminion near

Cairn table in the Upper Ward. There is not much to be seen at

Shalloch-on-Minnoch, but all the air is sacred, pregnant with history, and

to stand on the Session Stone with the ranged seats opposite and the white

stones of the parched bum beneath, brings the times that were in Scotland

wondrously near to us.

Here is William Gordon of Earlstoun's description of the

famous gathering:–

“Soon we left the strange, unsmiling face of Loch

Macaterick behind, and took our way towards the rocky clint, up which we

had to climb. We went by the rocks that are called the Rig of Carclach,

where there is a pass less steep than in other places, up to the long wild

moor of Shalloch-on-Minnoch. It was a weary job getting my mother up the

steep face of the gairy, for she had so many knick-knacks to carry, and so

many observes to make upon the way.

“But when we got to the broad plain top of the Shalloch

Hill it was easier to get forward, though at first the ground was boggy, so

that we took off.our stockings and walked on the driest part. We left the

bum of Knocklach on our left–playing at keek-bogle among the heather and

bent–now standing stagnant in pools, now rindling clear over slaty stones,

and again disappearing altogether underground like a hunted Covenanter.

“As soon as we came over the brow of the hill, we could see

the folk gathering. It was wonderful to watch them. Groups of little black

dots moved across the green meadows in which the farm-steading of the

Shalloch-on-Minnoch was set–a cheery little house, well thatched, and with a

pew of blue smoke blowing from its chimney, telling of warm hearts within.

Over the short brown heather of the tops the groups of wanderers came, even

as we were doing ourselves–past the lonely copse at the Rowantree, over by

the hillside track from Straiton, up the little runlet banks where the

heather was

blushing purple, they wended their ways, all setting towards

one place in the hollow. There already was gathered a black cloud of folk

under the rickle of stones that runs slidingly down the steep brow of

Craigfacie.

“ As we drew nearer we could see the notable Session Stone,

a broad, flat block overhanging the little pourie bum that tinkles and

lingers among the slaty rocks, now shining bone-white in the glare of the

autumn sun. I never saw a fairer place, for the heights about are good for

sheep, and all the other hills distant and withdrawn. It has not, indeed,

the eye-taking glorious beauty of the glen of Trool, but nevertheless it

looked a very Sabbath-land of benediction and peace that day of the great

Societies' Meeting.

The Session Stone.

"Upon the Session Stone the elders were already greeting

one another, mostly white-headed men with dinted and furrowed faces, bowed

and broken by long sojourning among the moss-hags and the caves.

"When we came to the place we found the folk gathering

apart for prayer, before the conference of the chosen delegates of the

Societies. The women sat on plaids that had been folded for comfort.

Opposite the Session Stone was a wide heathery amphitheatre, where, as on

tiers of seats, rows of men and women could sit and listen to the preachers.

The burnie's voice filled up the breaks in the speech, as it ran small and

black with the drought, under the hollow of the bank. For, as is quite usual

upon the moors, the rain and storm of the past' night had not reached this

side of the hill.

" I sat me down on a lichened stone and looked at the

grave, well-armed men who gathered fast about the Session Stone, and on the

delegates' side of the water. It was a fitting place for such a gathering,

for only from the lonely brown hills above could the little cup of

Conventicle be seen, nestling in the lap of the hill. And on all the moor

tops that looked every way, couching torpid and drowsed in the hot sun, were

to be seen the sentinels–pacing the heather like watchmen going round and

telling the towers of Zion, the sun flashing on their pikes and

musket-barrels as they turned sharply, like men well-disciplined and

fearless.

“The only opening was to the south-west, but even there

nothing but the distant hills of Colmonell looked in upon us, blue and

serene. Down in the hollow there was a glint of melancholy Loch Moan, lying

all abroad among its green wet heather and stretches of yellow bent.

"What struck me as most surprising in this assembly was the

entire absence of anything like concealment. From every quarter, up from the

green meadows of the Minnoch Valley, over the scaurs of the Strait on hills,

down past the craigs of Craigfacie, over from the deep howe of Carsphairn,

streams of men came walking and riding. The sun glinted on their war-gear.

Had there been a trooper within miles, upon any of the circle of the hills,

the dimples of light could, not have been missed. For they caught the sun

and flecked the heather–as when one looks upon a sparkling sea, with the

sun rising over it and each wave carrying its own glint of light with it

upon its moving crest.

“As I looked, the heart within me became glad with a

fullgrown joy."1

1 "The Men of the Moss-Hags," p. 314. (Isbister & Co.)

|