|

BORGUE

The County

Belle.

The county town is also in a way the county belle. For the

sober beauty which the instructed eye loves. there is nothing like her in

the south. The streets of Kirkcudbright are generally wide, the houses

well-set on good grounds of their own. Gardens peep out here and there. A

man passes with an easel under his arm. He is pretending that he is going to

work. There are also men down by the little quay who look as If they had

gone there to labour. It is all a pretence. They only smoke and watch the

tide covering the brown mud on the river banks. There are, however, within

hearing, busy little people and a busy schoolmistress, up above in the small

delightful schoolhouse. It hums presently like a hive of bees, and from it a

sound of singing is wafted as far as the bridge. Kirkcudbright river-front

is a pleasant place to dream on. The world's hum is far away. There is only

the children's chant in the school down by the bridge. Above all, there is

no cattle-market.

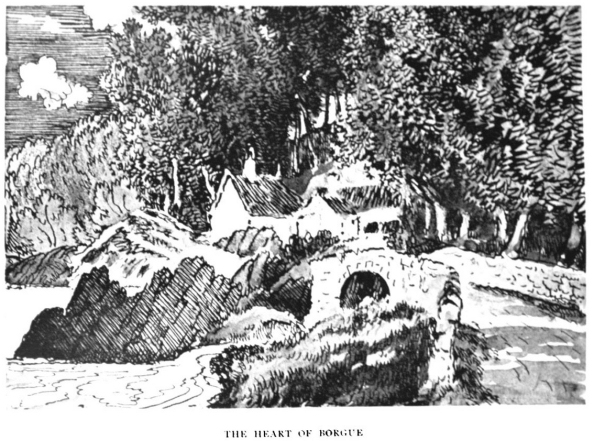

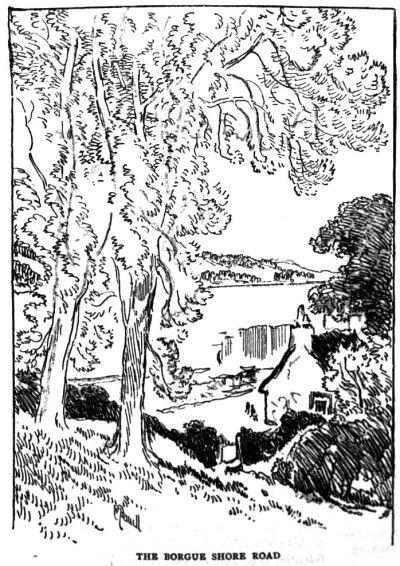

And then, how delightful are the byeways all about! There

is the walk by the town parks, with a dreamlike view back upon the ancient

town, with its towers and roofs, over a foreground of beehives and garden

patches. There is also that perfect failryland where one seeks for

Hatteraick's Cave, away past the lifeboat station. Best of all, perhaps,

there is the Borgue shore, all sandy cove and wooded slope, with old thorns

throwing themselves away from the sea, their arms outstretched and gnarled,

as if they were crying, "For heaven’s dear sake, let us get out of this

wind!"

Behind this again, in biddy hollows, are fine

old square-built farmhouses, with vast outbuildings, in what is the

brightest and most English part of Galloway. In one of these once on a time

two little boys played together in a large garden during the long-continued

heats of the dry summer 1868. The garden was cut up into squares by walks

which ran at right angles to each other. There were square plots of

gooseberry bushes, square wildernesses of pea-sticks, and square strawberry

beds in that corner where it was forbidden for small, sweet-toothed boys to

go, At the upper end an orchard ran right across, every tree in which was

climbable, and a wall, with a flight of steps over into a field, bounded

all. Great trees, generations old, surrounded the garden and orchard, and

cast here and there throughout it circular plots of pleasant shade amid the

garden squares. It was, said the wiseacres, too much buried in foliage to

make the best of gardens. But I can vouch that it suited two small boys that

summer-tide very well.

Honey-land.

Borgue is the metropolis of bee-land.

Everywhere indeed there is a vague hum in the air. The clear, pale,

aquamarine-coloured honey is sold even in the marts of London, and at the

proper season in Borgue itself every housekeeper's and good-wife’s cupboard

is a sight to see. There are first the products of orchard and garden–the

neat white pots of red currant jelly, the larger dishes of gooseberry

preserve, and marmalade with long amber straws lying across it, accurately

cut into lengths, and in the more plastic parts deep and rich like

cairngorms. After a while these get shoved a little farther back upon the

ample shelves, as the autumnal days creep in shorter, and the honey-

comb begins to arrive. There were no ”sections" in my day–no

hives scientifically contrived. The poor bees had perforce to be content

with their straw-built tenement, labouring late and early to fill it to the

utmost peak. This would have pleased them well enough, but alas I one autumn

night when the winds were stilI, or only blew up the strath with a kind of

sucking breath, there came a reek of burning sulphur. And the

Next day lo! combs of rich honey, ridged and shaped to the

convolutions of the "skep," were laid upon which other like huge piled

toadstools. The whole house was scented with the "straining” of amber honey

as the nets of gauze, swung between the backs of chairs, dripped their

slow-running silent-falling greenish freight into the appointed jars of tall

clear glass.

The farthest back in the good-wife's cupboard, and the

earliest in time, are the combs of the springtime–delicately green, as if

the bees had extracted some of the mounting sap. These pots seemed to be

fragrant with a faint, far-away, wildwood breath of crocus and wind-flower,

and the blowing heads of Lent lilies. The next are of fuller flavour–the

green alternating with amber and tawny, from the clover of pasture fields

over which the soft winds of June had blown through and merciful nights.

Then, golden-brown as the pools "'here the salmon sulk waiting for the

floods that they may leap upward, arrives the first heather honey, product

of the purple ling, which clothes the sides of the Bennan and gleams afar

upon Ben Gairn. Last of all, keen-scented as wood smoke, yet with a tang to

it like nothing else in the world, most precious conserve of leagues of the

true heather, wine-red and glorious, are certain dark-brown combs, through

which the knife cuts clean and luscious, revealing the scented essence which

the bees carried while the shots were cracking: and the grouse falling over

leagues of moorland There is usually most of this, for (though Borgue does

not think so) that is the best vintage, which the Master of the Bees keeps

to the last. The hives for the heather-honey have been carried in jolting

carts up to the purple sides of the Girthon Hills and there left–a busy

little colony–to their own resources, till the heather browns, and the bent

turns grey and rustling as silver-shakers in the keen winds of the moorland.1

In Borgue and the lower parts of Girthon, all farm life is

particularly rich and vivid. The farms are mostly large enough to be

well-to-do, and prosperity brings about them

1 V. “Cinderella,” p.116. (James Clarke & Co.)

all manner of mirth and country jollity–yet they are not so

large as to have become mere commercial concerns.

In these farm-towns life begins early, generally about four

in the morning, summer and winter. Hard work, without any halt or "Iet up,"

fills all the forenoon, till the midday dinner. After that, there is a

little more humanity in tile driving of man and beast.

"Afternoon is slack-water in the duties of the house, at

least for the womenfolk–except in hay and harvest, when it is full flood

tide all the time, day and night. So it will be ready seen that afternoon

happens far on in the day for such as have tasted the freshness of the

morning."

The Bread

Baking.

That is the time for the scone-baking, the cake-making, and

the pleasant duties of the housewife, or more frequently, house-maiden.

Blessed is he who finds himself at liberty at such a time.

"For" (says the Man of Experience) "there is no prettier

sight than this to be seen in Galloway, hardly even a blanket-washing when

coats are kilted for the tramping, when the sun deepens the colour on rosy

cheeks, and well-shaped ankles shine white as the flashing heels of Mercury

himself.

“Many promising courtships begin in this way. And a pretty

girl certainly looks her prettiest with arms bared well-nigh to the

shoulder, while the to-and-fro movement of the roller on the hake-board

brings out all the more fascinating graces of movement and play of dimpled

elbow.

"Rap! Rap! Rap! Rap! It comes to the ear in varied keys of

sound, dull and sharp, according to the thickness of the dough beneath. At

intervals a hand showers a delicate top-dressing of flour with a twist of

the wrist much admired by connoisseurs, and indeed worthy of being noted by

all This is generally accompanied by a smile at the attendant youth, so he

be a worthy one and deserving of having trouble taken with him. Immediately

after this the cakes need attending to. They have already been removed from

the round iron girdle which hangs over the clear fire–a fire

gentle, mild, and insinuating, no roisterous flame, but a

‘griesoch’ rather, mellow and mellowing all about it.

"The same pretty hands, the flour being touched away with

the corner of snowy apron, now take the oaten cakes and turn them at the

side of the fire, setting each at the proper angle to get the best of the

heat, so that it may come forth a worthy cake, light in the mouth, crisp to

the tooth, and much to be desired as fare fit for the gods! After this, such

knitting of brows–such poisings of head to decide whether the fortunate cake

is ready or not! Then–almost as if it were a theft, sweet and pardonable as

that other which (in intent) has been in the young man's head for the last

quarter of an hour, the least crumb is broken off the comer–follows a flash

of white teeth as it is tested, and the rest offered to the worthy observer.

"At this point the youth, if he have in him any manhood, or

that adventurous spirit which makes its way with maids even in staid

Galloway, slides off the corner of the table, and –but let all those who

have assisted at such bakings of the cake recall to themselves what happens

then. There be heads grey and heads white, and heads (alas, that ever it

should be so!) already growing thin or shiny a-top whose locks were once

like the raven. There be hearts which once bounded fiery as barbs under the

snowy baking-apron, that are now covered by the staid dove's grey of the'

old maid,' or oftener still by the widow's plain black–yet neither head nor

heart hath ever forgotten the baking of the cake, nor yet that tell, tale

print of a small floury hand upon a shoulder, on account of which, issuing

forth, the favoured swain endured, not all unwillingly, his comrades'

envious laughters.”1

The Cow

Milking.

To this follows (after tea, or the homely plate of

porridge) the time of the cow-milking, Shy lads look in at the byre door,

The bolder stand, each at the cow's tail of his chosen, as she milks. There

is much confidential talk abroad, the steady drill of the milk into the "Iuggies”

drowning it. "I will see ye Iater,” is the

1 "Cinderella,” p.70 (James Clarke & Co.)

burden of many a soft-sung song, and "the place where" is

well understood of both.

There is even a method in the letting out of the kye to the

dewey evening pasture, as it is written of one Jess Kissock, who being of an

envious nature did the business unsympathetically.

"In a little while the cow’s were all milked. Saunders was

standing at the end of the barn, looking down the long valley of the

Grannoch Water. There was a sweet coolness in the air, as if the Sabbath

were already near, which he vaguely recognized by taking off his hat.

"’Open the yett !' cried Jess, from the byre, door.

Saunders heard the clank and jingle of the neck-chains of Hornie and Speckly

and the rest, as they fell from their necks, loosened by Jess's hand. The

sound grew fainter and fainter as Jess proceeded to the top of the brye

where Marly stood soberly sedate and chewed her evening cud. Now Marly did

not like Jess, therefore Meg always milked her. She would not, for some

special reason of her own, ‘let doon her milk' if Jess so much as bid a

finger on her. This night she only shook her head and pushed heavily against

Jess as she came nearer.

"’Haud up there, ye thrawn randy!' said Jess, in byre

tones.

"And so very sulkily Marly moved out, looking for Meg, her

own mistress, right and left as she did so. She had her feelings as well as

anyone, and she was not the first who had been annoyed by the sly,

mischievous gipsy with the black eyes, who kept so quiet before folk. As she

went out by the byre door. Jess laid her switch smartly across Marly's

loins, much to the loss of dignity of that stately animal, who, taking a

hasty step, slipped on the threshold, and then overtook her neighbours with

a slow resentment gathering in her matronly breast.

“When Saunders Mowdiewort heard the last chain drop in the

byre, and the strident tones of Jess exhorting Marly, he took a few steps to

the gate of the hill pasture. He had to pass along a short home-made road,

and over a low parapetless bridge constructed simply of four tree-trunks

laid parallel and covered with turf. Then the bars of the gate into the hill

pasture dropped with a clatter, which came cheerfully to Winsome's ears as

she stood at her window looking out into the night."1

1 “The Little Sunbonnet.'''· p. 152 (T. Fisher Unwin.)

|