|

AUCHENCAIRN

IT was concerning the little, bright, rose-bowered,

garden-circled, seaside village of Auchencairn that I began my writing about

Grey Galloway. “The Raiders," indeed, was written at Laurieston, in the

heart of my own land. But all through the book, the cliffs and beaches of

Isle Rathan, the woods of Balcary, and the little white village of

Auchencairn kept coming and going.

If any traveller wants to see Auchencairn as I saw it in my

day-dream, and as I had seen it a thousand times with the eye of flesh, he

must of necessity visit Isle Rathan itself. But as this needs arrangement,

he had better walk first to the Torr Point by the Red Haven. Then if he care

at all for Galloway and the troubles of a certain Mr. Patrick Heron, he will

remember that it was concerning this place that that hardy adventurer wrote:

"It was upon Rathan Head that I first heard their bridle-reins jingling

clear. It was ever my custom to walk in the full of the moon at all times of

the year. Now the moons of the months are wondrously different: the moon of

January, serene among the stars; that of February, wading among chill

cloud-banks of snow; of March, dun with the mist of muirburn among the

heather; of early April, clean washen by the rains. This was now May, and

the moon of May is the loveliest in all the year, for with its brightness

comes the scent of flower-buds, and of young green leaves breaking from the

quick and breathing earth.

"Rathan is but a little isle–indeed, only an isle when the

tide is flowing. Except in the very slackest of the neaps there is always

twice a day a long track of shell, and shingle out from the tail of its

bank. This, track is, moreover, occasionally somewhat dangerous, for Solway

tide flows swift, and the sands are shifting and treacherous. So we went and

came for the most part by boat from the Scaur, save when l or some of the

lads were venturesome, as afterwards when I got well acquaint with Mary

Maxwell, whom I have already called May Mischief, in the day, of a lad's

first mid-summer madness.

Isle Rathan

”Here on the Isle of Rathan my father taught me English and

Latin, Euclid's science of lines, and how to reason with them for oneself.

He ever loved the mathematic, because he said even God Almighty works by

geometry. He taught me also surveying and land measuring. ‘It's a good

trade, and will be in more request,' he used to say, ‘when the lairds begin

to parcel out the commonties and hill pastures, as they surely will, It'll

be a better trade to your hand than keepin' the black-faced yowes aff the

heuchs (cliffs) o' Rathan.'

"It was a black day for me, Patrick Heron, when my father

lay a-dying. I remember it was a bask morning in early spring, The tide was

coming up with a strong drive of east wind wrestling against it, and making

a clattering jabble all about the rocks of Rathan.

"’Lift me up, Paitrick,' said my father, 'till I see agaIn

the bonny tide as it Iappers against the auld Toor. It will lapper there

mony and mony a day an' me no here to listen. Ilka time ye hear it, laddie,

ye'll mind on yer faither that loved to dream to the plashing o't, juist

because it was Solway salt water and this his ain auld Tour o' the Isle

Rathan.'

"So I lifted him up according to his word, till through the

narrow window set in the thickness of the ancient wall, he could look away

to the Mull. which was clear and cold, but of a slaty blue that day–for,

unless it brings the dirty white fog, the east wind clears all things.

"As he looked a great fishing gull turned its head as it

soared, making circles in the air, and fell–a straight white streak cutting

the cold blue sky of that spring day.

"’Even thus has my life been, Paitrick. I have been most or

my time but a great gull diving for herring on an east–windy day, Whiles I

hae gotten a bit flounder for my pains, and whiles a rive o' drooned whalp,

but o' the rale henin'–desperate few man, desperate few.'''

Here, then, it was that all my boyish romance of the sea

was wrought out. I own it. I am the dryest of dry–land sailors, The Channel

is wide enough for me, I do not bless the narrow seas. By no means do I wish

them a whole Atlantic broad.

But the sea as it washes into caves, and falls arching on

sandy beaches or clatters against the worn foot of some far regarding cliff,

touches all the romantic in me.

So, the very first time I landed on Isle Rathan, coming as

usual from the Scaur, I saw The book that should be written, and the tower,

and Patrick Heron and his father living there alone, The herd's house with

its silently playing children vanished, and I saw only the Rattan Tower on

the sea edge much as years afterwards, even as it is described in "The

Raiders."

"Now I must tell of the kind of house we had on the Isle

Rathan. It stood in a snug angle of the bay that curved inwards towards the

land and looked across some mossy boggish ground to a range of rugged,

heathery mountains, on which there were very many grey boulders, about which

the heath and bracken grew deep.

"The ancient house of the Herons of Rathan was not large,

but it was very high, with only two little doors to back and front–the front

one set into the wall, and bolted with great bars into the solid rock

beneath and above, and into the thickness of the wall at either side. The

back door opened not directly, but entered into a passage which led first to

a covered well in a kind of cave, where a good spring of water for ever

bubbled up with little sand grains dancing in it, and then by a branch

passage to an opening among the heather of the isle, which you might search

for all summer's day. But unless you knew it of others knowledge, you would

never find it of your own, The windows were very far up the sides, and there

were very few of them, as being made for defence in perilous times. Upon the

roof there was a flagstaff, and so strong a covering of lead and stone flags

that it seemed as though another tower might have been founded upon it. The

Tower of Rathan stood alone, with all its offices, stables, byres, or other

appurtenances far back under the cliff, the sea on one side of it, and on

the other the heathery and rocky isle, with its sheep pastures on the

height. Beneath the sea-holly and dry salt plants bloomed blue and pink down

near the blatter of the sea.

"Fresh air and sound appetites were more common with us

lads on the isle than the wherewithal to appease our belly cravings.

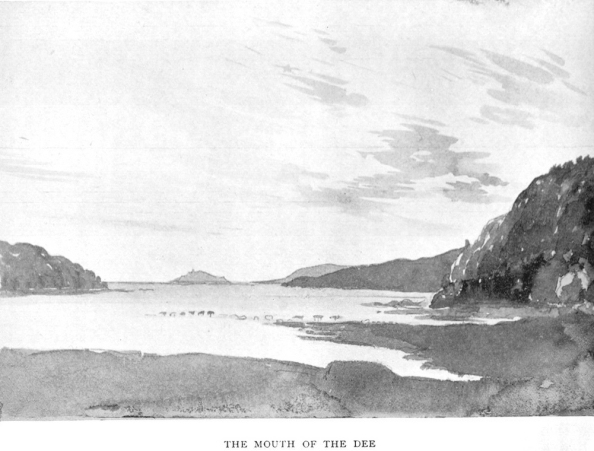

"Rathan Island itself lay in the roughest tumble of the

seas. Its southern point took the full sweep of the Solway tides as they

rushed and surged upwards to cover the great deadly sands of Barnhourie.

From Sea Point, as we named it, the island stretched northward in many rocky

steeps and cliffs riddled with caves, For just at this point the softer

sandstone you meet with on the Cumberland shores set its nose out of the

brine. So the island was more easily worn into sea-caves and strange arches,

towers and hay-stacks, all of sea-carved stone, sitting by themselves out in

the tideway, for all the world like bairns' playthings.

" In these caves, which had many doors and entries, I had

played about them ever since I was a boy1. I knew them all as

well as I knew our own back-yard under the cliff.

" In fine weather it was a pleasant thing to go up to the

highest point of the island, which, though little indeed of a mountain, was

called Ben Rathan, and view the country all about one. Thence was to be seen

the reek of many farmtowns and villages, besides cot-houses without number,

all blowing the same way when the wind was soft and equal. The morning was

the best time to go there. Upon Rathan, close under the sky, the bees hummed

about among the short, crisp heather, which was springy just like our little

sheltie's mane after my father had done docking it. There was a great

silence up there–only a soughing from the south, where the tides of the

Solway, going either up or down, kept for ever chafing against the rocky end

of our little Isle of Rathan.

"Then nearest to us, on the eastern shore of Barnhourie Bay,

there was fair to be seen the farmhouse of Craigdarroch,2 with

the Boreland and the Ingleston above it, which is always the way in

Galloway. Wherever there is a Boreland you rnay be sure that there is an

Ingleston not far from it. The way of that is, as my father used to say,

because the English came to settle in their 'tons,' and brought their

'boors,' or serfs, with them. So that near the English towns are always to

be found the boorlands. Which is as it may be, but the fact is at any rate

sufficiently curious, And from Ben Rathan also, looking to the westward,

just over the cliffs of our isle, you could see White Horse Bay, much

frequented of late years for convenience of debarkation by the Freetraders

of Captain

1 This refers more to Portowarren and the Douglashall shore

than to the harder rocks of Isle Rathan (Hestan).

2 Craigdarroch is, of course, a name willfully transplanted.

Yawkins' band, with whom, as my father used to say quaintly,

no honest smuggler hath company,"

It was on these wide sands also that, at the tum of the

tide, flounders were to be fished–and are, indeed, unto this day, Though

oftener I myself have done it on the flats over about the Scaur and Rough

Island! Here is how Patrick Heron did his work in the grey of the morning:–

"This morning of which I speak there was not a great deal

to complain of, save that I left the others snoring in their hammocks and

box-beds round the chambers of dark oak where they were lodged. The thought

of this annoyed me as I went.

Tramping Flounders

"It was still dark when I went out with only my boots over

my bare feet, and the chill wind whipping about my shanks. What of the sea

one could observe was of the colour of the inside of an oyster shell, pearl

grey and changeful. The land loomed mistily dark, and there were fitful

lights coming and going about the farm-steadings.

"It was cold and unkindly out on the flats, and there was

nothing except lythe and saithe in the nets–save some small red trout, which

I cast over on the other side, that they might grow large and run up the

rivers in August. So with exceedingly cold feet, and not in the best of

tempers, I must proceed to the flats and tramp flounders for our breakfast.

Right sorely did I grieve now that I had not awaked two of the others. For

Andrew Allison's feet were manifestly intended by nature for tramping

flounders, being broad and flat as the palm of my hand, Moreover, John his

brother was quick and biddable at the job – though I think chiefly because

he desired much to get back to his play about the caves and on the sand with

his ancient crony, Bob Nicoll.

" But I was all my lone on the flats., and it was

sufficiently dreary work. Nevertheless, I soon had my baskets full of the

flapping, slippery fish–though it was not nice a job to

feel them slide between your toes and wriggle their tails

under your instep. It was, however, somewhat pleasanter to hear them

by·and·by making their tails go flip-flap in the frizzle of the pan. For

flounders fresh out of the water is indeed food for the gods, and gives one

an appetite: with only thinking about it."

There are, however, other wild ways about Auchencairn without

going seaward. Screel and Ben Gairn tower high above, often menacing the

little white village with the clouds which gather so easily about their

craggy tops.

Screel

It is by no means time thrown away to take a stroll up the

purple side of Screel with Sammle Tamson, even

if it be not the traveler’s luck to find the true and only

"Cauldron of Ben Tudor."

"Finally, recalled to himself by a dash of rain in his face

from a passing shower and the tide washing simultaneously about his feet, he

strode away up the tangle of woodland which fringes the bay, and in ten

minutes was breasting the brae towards the dark heathery fastnesses of

Screel.

"As he made his way westward, with surprising craft Sammle

took advantage of every cover. He followed the deep lip of a peat moss from

which the fuel had been cut away for a hundred yards. He crouched behind a

boulder till a wandering herd with a couple of scouring dogs passed off the

sky-line. Nevertheless, it was swiftly, though with the utmost

circumspection, that he approached the tangle of sixfoot long heather which

conceals the descent into the Cauldron of Ben Tudor.

"The afternoon had early broken down into a thronging

procession of white cirrus cloudlets, varied occasionally by one of

haughtier build, as some towering cumulus overrode the lift with his bulk,

crenellated like a feudal keep. Shining glints of thunder-shower shot down

occasionally from these, and once SammIe felt on his face the sting of hail.

Having once arrived at the shaggy verge, from which through the interstices

of whin, broom, and rock-climbing ivy he could look into the untracked and

untravelled wilderness, Sammle lay down on his breast and studied the

landscape. Far out to sea, towards the open water of the firth, a schooner

hung off and on, waiting for night or tide But Sammle was no smuggler,

though possibly he might have been indicted for conspiracy."

Or, again, it is delightful to ride to call upon Silver Sand

in the old Tower of Orchardton. There are excellent roads nowadays, so there

is no need to founder your beast on the lairy Kirkmirren flats, as did young

Mr. Maxwell Heron in the time of the Levellers.

"We clattered over the hard sand and shingle on the Orraland

shore, went more slowly over the rugged foothills of Screel, and presently

bore away to the east across the lairy Kirkmirren flats. After a long

breathing gallop through lands covered with short sea-grass, and bloomed

over even now by the stone-crop and blue maritime holly, my father

dismounted in a little wood, and tied his beast to a tree in a place very

retired and secret.

"’Let them have their nosebags for a little here while we go

forward,' he said. 'Our good Silver Sand does not love overly many horse

tracks about his abode,'

“Orchardton Auld Toor.”

"Then, having thus arranged matters with satisfaction to

himself and the beasts, my father took along the first of Ihe broken dykes

(for we were now off his lands), and, making a detour to the right, suddenly

emerged upon an ancient grey tower, apparently ruinous and wholly desolate.

On three sides it was surrounded by hills, for the most part thickly wooded

with natural scrub, but on the other, towards the east, the ground was more

open. The tower looked upon a green valley, through which a little lane ran,

or, rather, loitered and lingered with a temperate gladness. Beyond that

again a high hill rose up abruptly and sheltered the tower from the sea.

There were the ruins of a considerable farm-town

near by, But all was now deserted–only in the midst an

ancient tower stood up, called, as my father now told me, the Round Tower of

Orchardton. I remembered now that I had seen it on a boyish ramble many

years ago, but that, being alone, I had taken to my heels and run away at

some fancied noise which I heard – a sound as of hollow knocking upon wood

high up in the tower – the pixies making some one's coffin, as I decided. So

I ran home at full speed, lest the coffin should prove to be mine, and the

little Pechts should catch me and fit me into it forthwith."

Of the

village of to-day, clean and delightful to view, clambering about its sunny

brae·face in a fashion all its own, I have little to say, Though I love it

too, and I am glad that it lacks the sea·front, the negro minstrels, even

the "excellent bathing accommodation" necessary for popularity. Quiet it is,

and quiet it is likely to remain. But mayhap that is the best fortune of all

– to be loved by a few greatly and constantly, rather than to be loudly

applauded and immediately forgotten by the many.

I close these random memories of the little shoreward village

by a picture of a parliament which meets, or used to meet thirty years ago,

nightly during the winter in every "smiddy" throughout Galloway. The sketch

was written in, if not of, the village. And those who have known Auchencairn

best and longest will understand best why it has been printed in this place.

|