|

KIRKCUDBRIGHT

A

SCOTTISH village is a strangely circumscribed place. Within a radius,

varying according to the width of ploughed land about it, everything is

known with photographic particularity. A man cannot get shaved without its

being publicly canvassed, and no words can express the minuteness with which

the characters of women are studied. But once out of the radius of ploughmen

who come to the smiddy to get their coulters sharpened, or their horses

shod, out of the ken of the herds who descend whistling upon the village

shops for flour and baking-soda, off the main roads by which the farmers and

their spouses drive to the weekly market, and you are in a region about

which nothing whatever is known or cared. A river may divide two parishes as

completely in interests and acquaintance, in bargain-striking and

love-making, as if it constituted the boundary of two hostile countries. A

mountain range or a stretch of wild heathery hills is a watershed of news

not to be passed over.

I

have at last arrived at Kirkcudbright in my wanderings, and that is why I

speak of the separations of Galloway rural Life.

I was a Castle-Douglas

boy, yet I know no one in Kirkcudbright only ten miles away. I could not

have believed that there was anyone in it worth knowing. The solitary

schoolboy (Laurence Kay) who went daily from our town to Kirkcudbright

Academy was looked upon as a kind of daring Stanley, familiar to an unholy

degree with the " Darkest Africa" at the mouth of the Dee.

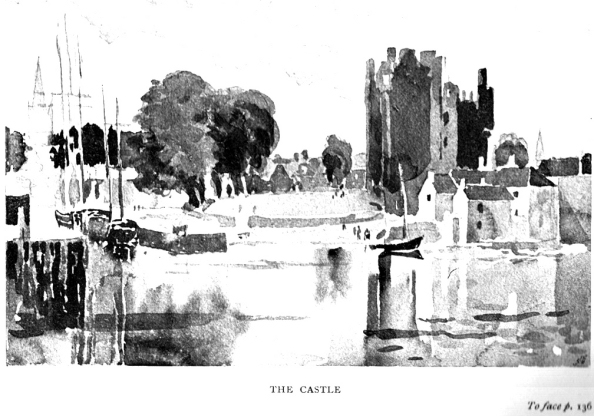

Even now I experience a

pleasant foreign flavour when I visit the seat of county government. It is

easy to do one's work there. As in a foreign land, there are not the

frequent invasions of friends who cannot be denied. In the quaint and

excellent Selkirk Arms, under Mrs. Carter's fostering care, I "'Tote some

part of "The Lilac Sunbonnet." And there is a grateful slumberous quiet

which rests the very soul about the bridge and the quay, or better still,

along the Borgue Shore and by the sea-girt Ross.

I remember as a lad

sitting dreaming on a seat by the sea-edge of St. Mary's Isle, a

writing-block on my knee. An old gentleman came and sat down beside me. I

put away my scribbling somewhat hastily, and the old gentleman, with the big

worn leather patches on his shooting coat, asked me if I had been sketching.

"No," said I, "only

trying to write–"

"Writing–ah, what?" he

demanded abruptly.

“Verses," I answered,

blushing. For at fifteen one blushes at everything.

"What are they about?"

was the next question.

"Paul Jones," said I,

"but I know very little about him."

“Read them to me."

I read, Happily I had

not proceeded very far before I came to the end. The trial was short. The

old gentleman smiled good-humouredly.

"Where did you get your

information?" said he. "Out of the 'History of Galloway'!"

“I think I can do better

for you than that," he said, musing; "where are you staying?"

I told him. It was at a

farm in the neighbourhood.

“Well, wait here a

little," he said. “I will see what I can find."

He disappeared into the

wood, and after twenty minutes or so he came back without his, gun. but with

two books under his arm.

"Here they are," he

said; "you can keep, them. I find I have another copy."

I declare that I was so

much astonished that I forgot to thank him. But he understood, patted me on

the shoulder. nodded, and said, smiling. "Good day to you."

”Who was that?" I asked

of a gamekeeper who had been hovering in the offing during our second

interview.

".Who is that?" he

repeated after me in astonishment; “do you mean to tell me that ye dinna

ken!"

"No, I don't," I said,

but anyway he is very kind, He gave me these two volumes of ‘The Life or

Paul Jones.'''

The man stood

open-mouthed.

"The Yerl gied you thae

twa books! –The Yerl–"

He could say no more,

and I left him standing still with dropped jaw, unable to digest his

astonishment.

I have the books still,

and they bear the arms and autograph of the last Earl of Selkirk.

|