|

THE GATES OF GALLOWAY

TOGETHER WITH THE TALE OF "HOW THE SCHOLAR CAME HOME"

Dumfries.

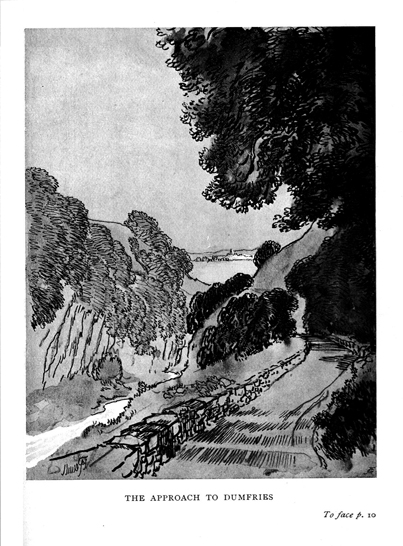

WHEN you step out of

Dumfries station under the full moon, as I did the other night, and see the

needle-pointed electrics of the line and the mellow glow of the Edison-Swan

bulbs over at the Railway Hotel mingling with the red and green and yellow

of the more distant signal lamps, you are conscious of a certain brisk

elation, a verve and movement which is not provincial. In fact, there is

something about the clean sharp-cut brilliance of Dumfries not unlike some

of the newer French towns–or even one of the more frequented suburbs of

Paris.

Kirkcudbright.

Kirkcudbright, on the

other hand, is an old Dutch town, stranded, and as it were half-submerged,

on some forgotten beach of the Zuider Zee. Yet the smaller burgh is by far

the more picturesque and fruitful in suggestion, at artistic and literary.

Or so at least it appears to me. Mysteries, solemn and far-reaching, stir

and rustle about it. Imagination quickens at the thought of setting foot in

it. Legend clothes it as with a garment. In the sough of its Isle woods. in

the solitary thorns which grow for ever in Mr. Henry's "Galloway Landscape,"

and can be seen in their gnarled reality on the Braes of Loch Fergus, there

is something wistful as the Solway winds and mysterious as the Picts

themselves.

But the landscape

environment of Dumfries, her brisk atmosphere of trade, are as unromantic

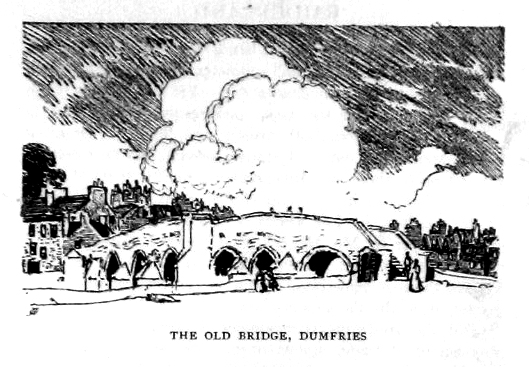

and actual as her excellent pavements. In spite of Devorgilla's Bridge and

the memories of the sweet sad heart which lies beyond it at Dulce Cor, the

"Queen of the South" is of today, and was crowned but yesterday.

Burns.

Only on a wet autumnal

gloaming of wailing wind-gusts, shining causeways, and clammy fallen leaves

is she at all impressive. For then, at least, we can stand and imagine the

funeral of Burns winding its black and tragic way up past the Mid Steeple.

For through all the cheerful clatter of the Wednesday market and above the

clanking tumult of the Junction, somehow the last days of Robert Burns

overwhelm the heart of the thoughtful visitor, and subdue his mood to a

fixed and sober melancholy. One looks in vain among the myriad

advertisements of inks and soaps and mustards upon the station walls for the

one motto which should be emblazoned there–black on a ground of gold–

"THE NOBLEST SCOTTISH HEART

BROKE HERE."

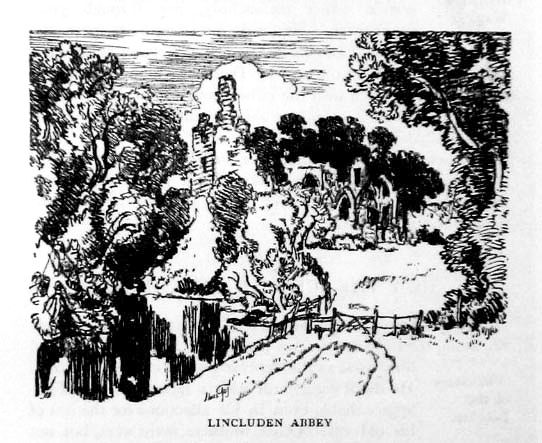

The Banks of Nith are fair

and very fair. Slow, soft, and deep it runs above the bridge, and lies like

a wind bound lake round the bend towards cloistered Lincluden. But for me, I

own that I am glad to be across Devorgilla's crumbling arches and turning up

the Glen of Cluden–or still further, out upon the blasted heath beyond

Mossdale, where in a better day he composed "Scots Wha Hae," facing the

lashing volleys of the rain with a hero's heart.

I own it–in Dumfries I am

as a stranger in a strange land.

A Strange Land.

I visit the Queen of the

South. I stall me in her comfortable hotels, still but uneasily, like a

horse in an un-kenned stable. There are, however (praise the pigs!), fellow

Gallovidians to be met with even here, and when I visit them we sit and talk

about Galloway a little sadly, as if we were in Cape Town or Timbuctoo.

"This is no our ain hoose,

we ken by the biggin' o't" -that is, by the raw beef sandstone of its

villas, and (humbly I confess it) by the sanitary excellence of its streets.

Cross Devorgilla's Brig, and the senses inform you at once that you are in

Galloway, a more primitive land, with all things more in a state of nature,

but, so they tell me–and the detail is diagnostic–with cheaper taxes.

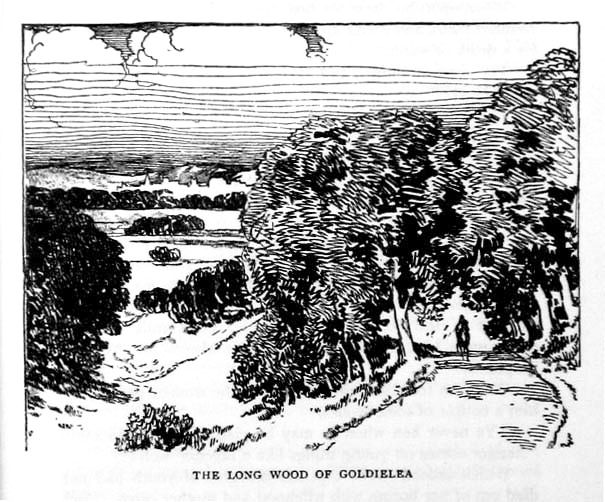

The Beauties of this

Foreign Shore.

Nevertheless, Dumfries is

delightful in itself, and many guide-books will inform the curious of the

sights thereof. But for me, I yearn mostly to cross over to the green braes

of Cargen and Cluden, to lose myself in the haunted woods of Goldielee, and

to tread the solemn aisles of Sweetheart. Maxwelltown and the bridges–the

waterfront of the two towns (mother and daughter), please me most,

especially the view from the Galloway side, though I liked Maxwelltown

better when it was still called Brigend. Over the water the old prejudice

against the city of Burns and Bruce stands fast. Once (says a not too

veracious chronicler) they put out a legend over a grocer's door in

Maxwelltown–"Coorse meal for Dumfries masons!" Whereof being advised, the

'prentice builders of Dumfries crossed the bridge and broke many windows!

Yet to take the Holywood

road by night, and look down through the summer leaves upon the Nith lying

cool and calm and deep beneath, with waifs and strays of moonbeams deflected

and reflected till they waver faint and mysterious as the northern lights,

is to taste anew the wonder of the world, and to believe in water-kelpies

and mermaidens combing locks of gold under the shade of birken shaws.

The Dreamy Nith Valley.

The meadows of Netherholm

and Carnsalloch, deep-bosomed in woods, Quarrelwood, steeped in memories of

the Covenant men and the meetings of the Cameronian societies, the

far-spying uplands of Kirkmahoe–these all come back to the nature-lover

laden with the scent of clover and wiId thyme. All the summer long the bees

are booming among the blossoms, drowsy with the luxury of sweetness, and one

can never forget the peculiarly dreamlike atmosphere that overhangs the

valley of the Nith, and which has been most perfectly expressed in art by

the brush of James Paterson of Moniaive.

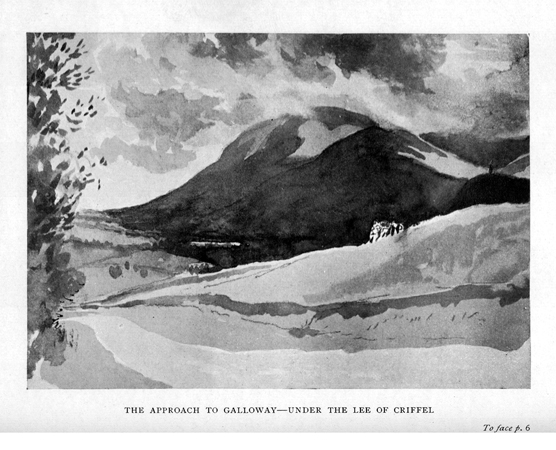

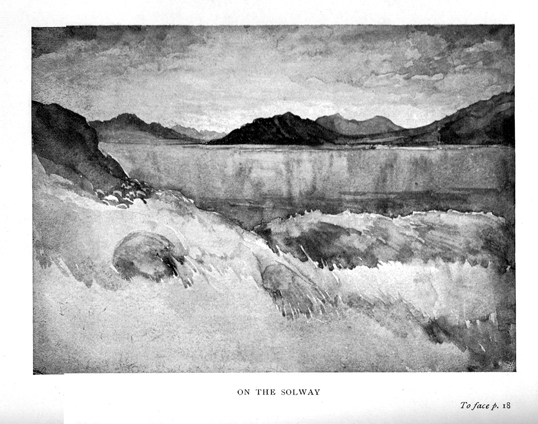

Still, for all that,

Dumfries is but the gateway of better things-rougher, more rugged things. By

the grit and rasp of her Silurian beaches, with the boulders of "auld granny

granite gimin' wi' her grey teeth," Galloway beckons us, holds us, attaches

even the stranger within her gates till he loves her

with the intemperate zeal of

the pervert. Dumfries is a green country, but we seek the Grey Land.

Thornhill.

Other things lead up to

Galloway, but she is still the goal. Come your ways down by Thornhill and

visit the famous strength of Morton on its little hill. It is one the most

stunning and picturesque ruins in Scotland. Visit Crichope Linn, and see the

rock whence (as tradition avers, and John Faa, Lord and Earl of Little

Egypt, narrates) Grier of Lag cast the boy who carried the minister's

bannocks when on his way to the cave near the Grey Mare's Tail. Explore the

bowery ducal village itself. Follow the flashings of the Scaur Water with

Ralph Peden and Daft Jock Gordon–now dashing and roaring in a shallow linn,

and again dimpling black in some deep and quiet pool. Or, northward away

with you along Nithside towards the deep defile of Menick, the great purple

overlapping folds of the hills drawing down about your shoulders as you

pass.

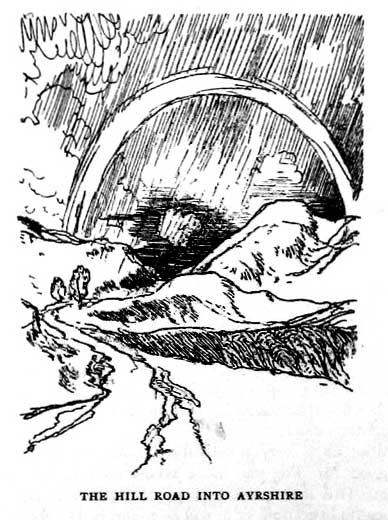

The Enterkin.

Or lastly, approach

Galloway by the Enterkin–that "deep and narrow glen" so excellently

described by the author of "Robinson Crusoe," and the scene of one of the

most daring of Covenanting exploits–"a most wild and fearsome place, where

the hills draw very close together. One of the precipices is called Stey

Gail, and is so steep that the sheep grazing upon it are like flies but

halfway up!" So plain-spoken Mr. Daniel Foe remarked when he passed that

way. On the other side of Enterkin there rises still higher, and almost as

steep, the top of the Thirlstane Hill, where is one place where the water

runs down the cleft of the mountain and the descent is perpendicular like a

wall-so steep, indeed, as Defoe saw it, that "if a sheep die it lies not

still, but falls from slope to slope till it end in the Enterkin water."

All which is very

remarkable. Only one must consider that good Mr. Foe was more accustomed to

the ascent of Ludgate Hill than to the steeps of Enterkin, and a much more

credible account of it will be found in Dr. John Brown's charming paper

descriptive of his walk through the pass in later and less exclamatory days.

The Four Foot Way.

Nevertheless the railway

is, after all, Galloway's main approach. It used to have two front doors,

and though the rival companies have to some extent amalgamated, In so far as

the Province is concerned, the employees still keep up the feud. I am

reminded of my old friend Frank Jardine (his name was cognate to that), now,

alas! passed from the earth upon which his feet made so firm a footmark. How

often have I seen his portly presence gracing the "Caledonian" platform at

Carlisle! When first I knew Frank he was traffic superintendent on the

Portpatrick line. From his youth he had been trained in a simple creed of

two articles–" to swear by the deep indigo blue of the 'Caledonian' and her

trim engines, and to hate the apple-green hulks of the 'Glasgow and

South-Western.'"

Frank the Abdiel.

So when in an evil day the

lines amalgamated for the conduct of their Galloway traffic, Frank applied

for a "shift" at once. It was bad enough to see the carriages of the hated

G. & S. W. passing and repassing, the but to be compelled to hunt officially

for their lost trucks was more than Frank could bear. So the P. P. R. knew

him no more, and he fled to districts where the Banner of Blue of the

"Caledonian" was still unstained by any barsinister of South-Western

apple-green.

Rest to thine ashes, Frank,

faithful servant! Perchance on some celestial line you are to-day hunting

non-arrivals, expediting tardive heavies, and charging up demurrages to the

debit of disembodied consignees. At least in this life Frank was faithful to

his owners and died in his duty–no bad theology, thought Captain Smollett

after he had flown the Union Jack over the famous block-house upon

Stevenson's Isle of Treasure.

Other Gates to Galloway

Land.

Anciently there were many

gates to Galloway, now to all intents and purposes there is but one. Behind

horseflesh over the bridge of Dumfries, on foot by Devorgilla's, or by that

which carries the shining metals of the Glasgow and South-Western railway,

come nineteen out of every twenty who view the land of bog-myrtle and peat.

Girvan.

A few struggle in by Girvan

and that whaup-haunted single track which, like an insult to nature, scrapes

its way past Barrhill and over the peaty watershed into the long glen of the

Luce Water. But those who come this way have a strained, almost terrified

look, as of men who have passed great peril and do not care to tell the

tale.

Belfast.

Still fewer adventure

across from Belfast Lough to Stranraer, seeing behind them the light of

Donnachadee lighthouse burn steady across the stormy strait-as from the

windows of a Back-shore farmhouse many and many a night I have watched it.

Drove Roads.

There were also in old time

the drove roads, up which two sorts of "nowt" took their way. The first were

sheep and bullocks which returned not again, but dreed their weird as mutton

and beef after their kind in faraway markets. Then twice a year they were

trodden by that other sort of cattle who, as Burns irreverently says, "gang

in stirks and come oot asses," as they hied them collegewards over the green

sward. Some, doubtless, issued forth long of ear. But not all–by no means

alI that have gone that way. There is Carlyle, for instance, who, though a

mere Dumfriesian (and Annandale at that), deserved to have been born in the

Free Province. He was never appreciated in the dales. He and all his clan

were thrown away upon Ecclefechan. They were not sib to that soil. They

should have dwelt under the shadow of the Windy Standard, a name obviously

invented on purpose to be the oriflamme of the stormy Apostle of Silence.

Carlyle.

Though Carlyle ought of

right to have turned off down the Annan Water, yet once at least, coming

from visiting Irving at Glasgow, he travelled by the Galloway college road,

whereon he and his friend "tired the sun with talking and sent him down the

sky." On the famous field of Drumclog they held their chief

conference–"under the silent bright skies, among the peat-hags of Drumclog,

with the world all silent round us–the brown bog all pitted and broken and

heathy remnants and bare abrupt wide holes, mostly dry: a Oat wilderness of

broken bog, of quagmire not to be trusted "–with the lion of Loudon Hill

looking down on them as serenely as may be.

Dear, inexpressibly dear

and near to me is the picture of these two, searching out each other's souls

as only young men will-proving all things, yet eager to hold fast that which

is good. But–ah too confident certainty of youth–convinced also that they

will always be able to hold it fast.

No wonder that the memory

of the colloquy is still "mournfully beautiful" to Carlyle fifty years

after.

Drumclog.

"I remember us sitting

down," he says, "on the brow of a peat-hag, the sun shining, our own voices

the one sound. Far away to the westward over the brown horizon, towered up

white and visible at the many miles of distance a high irregular pyramid.

Ailsa Craig we at once guessed it, and thought of the seas and oceans over

yonder."

Yet perhaps it was a vision

of the things that were to be–the Unattainable shining before the eyes of

these two great young men–the Might Have Been, the last glimpse of

child-hood's glittering cloud land before the mists of common day closed

about them and the night drew down.

Other two blessed northerly

gates there are, both still trackable and rideable even in these days of

motor and cycle.

The Windy Standard Way.

I have tried them on foot,

which is perhaps the better way. One, a road distinguished by a certain

sweet melancholy, lies through great slumberous hills, wide green valleys,

past the western Windy Standard (blessed name!). Beyond, it stretches away

along Loch Doon and by Dalmellington, from thence making a triple track with

the railway and Doon Water all the way to Ayr, where it meets the shining

salt levels of the lower Firth of Clyde.

I knew a young lad who,

once on a day (and on a night) trod that way, and the memory of his

journeying is still fresh, though his flaxen locks begin to sprinkle with

the pepper-and-salt of time.

HOW THE SCHOLAR CAME HOME

The Story of the Scholar.

He was young, only a boy

indeed, too early sent to college. So, being the only one in the parish, the

Scholar they called him–and as the Scholar we will unravel his story. He

dwelt on a farm with a father, stern and unapproachable even in his

affections for the son of his old age. Other brothers there were, but not

jealous like Joseph's brethren–rather silent, kindly men, lifting every

burden that the father's stern eye would let them touch, smoothing the

Scholar's path, and ever anxious to thrust the thorns and fallen rocks from

before his feet. In short, being so much older than he, they were like

fathers and brothers all at once.

One day at the beginning of

the hay harvest or thereby, it chanced that there was announced a cheap

railway excursion from a neighbouring town to Ayr–some cattle show or sheep

tryst the effective cause. Two of these elder brothers (very much not

according to pattern) having clubbed their small earnings resolved to go,

taking the Scholar with them. But a sudden improvement in the weather

summoned all hands to the meadow-hay. In a few days the crop might be

spoiled. To Ayr Show, therefore, they could not go.

But our Scholar, being of

little practical utility at scythework, could go an he would. Willing? Aye,

truly, and anxious. A most triumphant and victorious Scholar! His father

even bade him go, somewhat harshly–with the stem reason roughly expressed

that his absence would save more in meat, than his labour in the meadow

would earn if he remained. Now this father loved his youngest born, his

unmothered boy. Even as Jacob loved Joseph, so he loved him. But this was

his Scottish fashion of fitting him with the robe of many colours. The old

man owed it to his very love to be stern and hard with his youngest son.

There are men made that way. Many pitied the Scholar and thought him hardly

used.

"The heart of the old man

is set on his first-born sons because they are more help about the farm!"

That was, frankly, the countryside opinion. But these unusual elder brethren

were not deceived. They knew to whom the best robe belonged, and whose head

would one day be held the highest. So, being neither Jews nor Patriarch;

they made no bones about bowing down in service to their Scholar.

And he was a good Scholar.

In no way did he abuse his position. Indeed his father faithfully charged

himself with that.

So very early in the

morning of Ayr Show day the Scholar started off for the town through the

cool dewy light of the summer gloaming–two of the brethren, those two who

had given him part of their savings, convoying him on his way. A happy

Scholar, a Scholar stepping on air and elastic sunshine–his Sunday boots

a-squeak on his feet with the feeling of holiday! His very white shirt and

collar rasped happiness about his neck.

Add to these things the

elation of the spinning train. Think how at junctions and waiting-stations

he watched the leisurely manipulations of greasy engine-drivers and grimy

firemen. Never before had he been on a railway, and even now he can recall

the slack drip-drip of the great leathern hose through which the engine had

just taken its Gargantuan draught, the alert stiff-jointed armature of the

signals up in the sky, as fresh and gay as paint could make them! Then at

long and last Ayr, the blue Firth of Clyde, and the wide bay between the

headlands clipping and slapping in the brisk north wind, which made it an

indigo and foam to the boy's eyes.

The Heads of Ayr.

The Scholar made straight

for the shore. Beautiful shells beset him, chipped and rounded pebbles, the

famous agates of the Heads of Ayr, tempted him at every step. Yet he fled

back that he might have one glimpse of Burns's Cottage. But even here he

secretly grudged the time which he lost, away from the seashore and the

strange electric clapping palms of the little waves as they cheered each

other on. Think of it! He had actually never smelt salt water before.

"Cattle! Tryst! Prizes!

Competitions! " They were all a vain show! The Scholar never once thought of

them. He could see sheep and bullocks enough at home–and he liked them,

especially if they would only stay calves and lambs. But here –!

Well, the Scholar thought

he knew something better. Somewhere in the distance he divined the mool and

brool of the showyard. He resented the very aroma as it came to him down the

wind. He saw gaily-dressed girls and solid country men in black clothes and

wide-awake hats of shepherd shape moving steadily to the one goal. But for

him–why, Greenan Castle, the wide pleasance of the shore, the tang of the

seaweed in his nostrils, the rasping saltness of the pebbles when he licked

them to bring out the colours–that was life. "Cattle shows–faugh!"

It was indeed a high day of

tumultuous gladness and fine confused emotion to the Scholar. He forgot

everything but the heavens above calling to the earth beneath, and the seas

applauding both. His spirit was at one with Nature–a most imaginative and

dreamy Scholar, though at that time noways sentimental. He cared no more for

a girl in holiday white

than for a sea-bird. Both

wore the same colours, that was all. An Arcadian born out of his due time,

the Scholar was still constrained by cheap excursion trains and the mystery

of return tickets.

Not that the Scholar minded

either of these. If he had, this true tale would never have been written.

He only wandered on and on, and the first thing which reminded him that he

was not a spirit in unison with the air and the water and the earth, was a

most persistent and appalling hunger. He had been vaguely conscious of a

want for some time, but the sight of a good housewife at a cottage door near

the shore setting out a bicker of porridge to cool, localised the vacancy

sharply in the pit of his stomach.

Whereupon he drew his

hoarded pence out of his pocket, counted them, and going up to the woman he

asked cunningly for a drink of water.

The woman smiled, and said,

"Ye will be wantin' it in a milky bowl? "

The Scholar smiled, and

said as to that he had no objection.

"Then come your ways ben,"

answered the goodwife, "and sit ye doon. Ye'll be a stranger corned to see

the show? Weel, an' what for are ye wanderin' here? Frae Galloway? A' that

road? To see Burns's Cottage–and the Sands–and Ailsa? Ye hae corned far for

verra little! But there–that will put some fushion intil ye, and then ye can

gang your ways back to the showyaird and get in for saxpenee after the

judgin' is by ! "

And so and so, with

porridge and good milk and his pence upon him, the Scholar tasted the

wholesome Ayrshire hospitality.

When he took his leave Ayr-ward,

the woman pressed on him a couple of soda-scones.

"Ye never ken when ye may

be glad O' them," she said; " hunger comes on young things like a ravenin'

wolf!"

Which indeed shows that the

thoughts of youth had not died out of her bosom with wifehood and mother

cares. And indeed the Scholar had great reason to bless her foresight and

motherhood before all was done.

But on the way to the

station the boy's good angel deserted him – or perhaps was momentarily

displaced by a better angel. For the Scholar lingered, just as if there were

not such a thing as a railway time-table on the face of the earth. And

neither there was–for him. For when he demanded with weak and feeble

utterance when the train would start, he was told that it had already

gone–and that his ticket, being an excursion pasteboard, would frank him by

no other.

What then must he do?

That was easy buy another!

But the Scholar had no

money, or not nearly enough to purchase the meanest single ticket that could

be bought–no, not so much as "a half." So, with a sudden thrill that was not

all unpleasant, he turned away from the crowded station, going out through

the rabble, growing noisy now and staggery upon its legs.

The Scholar never thought

of going to besiege any great man in authority–station-master or other. He

would as soon have petitioned Her Majesty's High Court of Parliament. He

only turned away a little sadly, wandered from street to street making up

his mind, suddenly made it up, and bought two Jew's loaves. He can smell

those loaves yet. They were a day old, and ripe for the tooth. Each had nine

currants in, four above, five below, all visible to the naked eye-no

deception!

Then he went up to a

shepherd with his dog, all electricity and curling tail amid the unwonted

press, and demanded to be put on the Carsphairn road.

"Boy," said the herd,

looking down upon the Scholar as if from a mountain-top, "ye are never

thinkin' of ga'in' to Carsphairn the nicht?"

"Aye," said the Scholar,

speaking with a kind of joy; "for when I get to Carsphaim, I'll be near-hand

half-road hame!"

He had heard his father say

so.

Then the herd, thinking

that he was being jested with, raised his staff to strike. But the Scholar

did not run away, jeering as is the way of callants in the wicked town of

Ayr. He stood his ground and repeated his question.

"Which is the road to

Carsphairn–the best road–the quickest road?"

"There is but ae road to

Carsphairn," said the herd, "and as I gang wi' ye a bittock–ye may een bide

the nicht wi' me, and we'll see what can be dune wi' ye in the mornin' !"

The CarsphairnRoad.

The Scholar thanked him

kindly. But on the morrow, you see, he had promised to be back at that

farmhouse near the Dee Water to help with the hay. His father–still more his

brothers–would be wild about him. Elder Brother William train looking for

him! Go he must and would. And so, if he pleased–the road to Carsphairn?

And the herd, with his

sheep-dogs, his pleasant moorland eyes under the shaggy eyebrows, bleached

and tufted like those of his own collies, soon dropped behind, and the

Scholar fared forth alone.

Dalmellington.

In an hour he was clear of

the turmoil. In two he had settled into his stride, and was devouring the

miles. At Patna he had his second streak of luck, and got a lift to

Dalmellington, together with much counsel from a farmer who had driven his

gig all the way to Ayr to get his "greybeard" filled, and who felt in the

gig-box every hundred yards or so to see that nothing had happened to it. No

one could take that responsibility but himself, but it was almost too much

even for him.

To this friend our Scholar

owed no little. He also urged him to stay the night. But the Scholar pressed

on, eager at least to put himself within the confines of Galloway. He

yearned to see green Cairnsmore swelling with its double breasts; for, from

the craggy summits of his paternal hills, on clear, northerly-blowing days,

he could see the cloud shadows fleck great Cairnsmore 0' Carsphairn. So up

the long valley sped the Scholar, under the gentle cloud of night. Here, in

June, the nights are mostly clear and merciful But there was a weird quality

in the light. Towards twelve of the clock every broom bush loomed up like a

phantom leaning forward to clutch at his throat. A scurrying rabbit set him

quivering with vague but very real alarms. So he passed from adventure to

adventure. At Meadowhead something "routed" at him from over a wall–a white

face with horns it was, and sufficiently appalling. The Scholar did not wait

to investigate, and the next mile was his quickest time.

Presently he found a

shelter by the wayside, under an overhanging hank, with heather deep above

and below. The Scholar buttoned the neck of his jacket and curled himself

up, with a sigh like a tired puppy. When he awoke the sun was shining on the

green flanks of Cairnsmore. He knew it by instinct, though its rearward

parts looked very different.

The Scholar leaped to his

feet in haste, and, without more than the shake and yawn of a stretching

dog, trotted out again on the southward road.

Carsphairn.

At Carsphairn a woman,

sweeping her doorstep in the clear early light, looked curiously after the

small hasting stranger. But he was out of sight before she could make up her

mind what to say to the lad, though she had good in her heart. A vast amount

of things, good and evil alike, never happen in Galloway, just because the

good and ill doers cannot make up their minds to take action in time.

The rest of the way, so far

all the Scholar knew, was a maze of wearied feet and swimming head. He grew

too tired to care about being hungry any more. On and on past Dalshangan,

Strangassel, we can see the little hasting figure growing ever more

white-faced and pathetic.

The Glen Ken.

At Glenlee a dog barked at

him, and the Scholar created a momentary interest in the dog's master, a

ruddy young gentleman with a gun over his shoulder. Then he saw the houses

of St. John's Town glisten white, across on the green bank of the Water of

Ken.

As he passed New Galloway,

his, pallid face and limping feet brought the good-wives to the doors. But

he hasted through and so out of their reach into the leafy aisles of Kenmure

wood.

Then the loch opened out,

and the Scholar seemed to walk light-headed in a world of misty brightness.

Flashes came and went before his eyes, and he reeled with mere sleep. Nay

more, in very truth, I think he was sometimes asleep upon his feet, hasting

and halting ever southward.

Home.

About noon he came to the

beginning of his own territories, and a herd on the heather over a dyke

called to him by name to know what he did there when he should have been in

the meadow. But the Scholar was too far gone to talk. He could only move his

lips, and make a faint whistling noise in his parched throat.

An hour after he stumbled up

the little green loaning, across the watering-place, and so by the

cattle-yard to the door. He fell across it. His father lifted him up in his

arms and carried him in. Then something was poured down his throat, and with

a nasty taste and a burning feeling in his mouth, he came to himself. He

felt comfortable now, and by-and-by could talk. His father listened till he

was done, and then said sternly, "Put on clean stockings and your everyday

claes, and away doon with you to the hay! That will learn ye to miss trains,

and put them that love ye in fear for your life!"

And because obedience was

the first if not the sole law of the house, the Scholar rose and hirpled

painfully meadow-wards, where his elder brothers greeted him with joy, and

Elder Brother William, with a careful eye on the coming of his father, made

him a lair behind a cole of hay. Upon this the Scholar fell down, and passed

(even as a candle is blown out) instantly into dreamless sleep.

Nor did his father come

near the meadow all the afternoon, but stayed on the hill with his

sheep-knowing very well what would be happening down there where the forks

were tossing out the hay and the warm June winds blowing. For though a stern

man and a just, this father had pity unto his children.

Now the very commonplace

moral of all this is that the Scholar, though still dreamy and absent-minded

beyond words, has never missed another train in his life.

And this is the last of the

Ways into Galloway, and one which is not trodden in such fashion twice.

|