In endeavouring to write a history of the Ancient Capital

of Scotland, we are reminded of the fact that no writer has ever attempted

to give a consecutive narrative embracing the first ten centuries of the

Christian era. For that period anything of historical value is very

fragmentary; and we therefore must fall back on such material as we can

obtain, in order to form an intelligible narrative. It would be a great

acquisition to our historic literature if we were able to produce an

authentic history of the Ancient Capital from its foundation onwards, but

the difficulties in the way are insurmountable. Where, for example, are we

to begin; and whom are we to believe? For the early history of Perth is

involved in obscurity, and research has not greatly improved the situation.

Agricola's was the third Roman invasion of Britain, and it occurred in the

reign of Vespasian in the first century. From all reports the former was a

man of temperate judgment, a skilful military commander, and well qualified

to hold his high office. It was in the third year of this campaign that he

is said to have got as far as the Firth of Tay, but the actual position of

his camp cannot be finally determined. Any attempt to do so now could only

be conjecture. It is said by some writers to have been at the junction of

the Tay and Almond, but no trace of a Roman camp can be discovered there. It

is at this point that we meet the first and greatest difficulty. What was it

that induced the Roman general to establish the headquarters of his army on

(presumably) the North Inch? for we must take the Castle Gable district, the

Skinnergate and Watergate, the subterranean street under St John Street and

Princes Street, and from that to the river, as very probably the site of

this encampment The old castle which stood in that locality is believed to

have been built by him. The Inches and the river would undoubtedly afford

him inducements to pitch his camp, which, judging from other Roman camps in

Scotland, would be on a considerable scale; and this is supposed to have

been the beginning of what afterwards became the Ancient Capital.

In the darkness and obscurity which prevailed over

Scotland at that early or pre-historic period, we are much interested to

know what was its condition; were the natives purely Picts and Scots, or

were there other races in addition to these? We have no reason to suppose

that any race, other than the Picts and Scots, occupied our more immediate

locality. It was a savage period, as rude as that of Somaliland and of the

native races of Africa to-day. The Romans were the harbingers of a new

economy. Their arrival sounded the death-knell of the barbarians, and they

introduced, by the aid of military conquest, the dawn of civilisation, which

led eventually to the extermination of the native races, and their slow but

gradual replacement by a race of inhabitants who became more enlightened and

civilised. The first six centuries of our local history were essentially an

age of Paganism, but the seventh and eighth and succeeding centuries

witnessed the development of an improved state of the country; and

undoubtedly the civilising influence inspired by the Romans achieved a

tremendous accession of strength when Kenneth M'Alpin, by military conquest,

amalgamated the Picts and Scots in 843. This victory was as great in its

time as Bannockburn was in the fourteenth century. It substantially settled

the civil war that had raged for centuries in our immediate neighbourhood,

procured a lasting peace between the two fighting native races, and paved

the way for subsequent peace and civil and religious liberty. Assuming then

that Agricola erected dwellings for the use of his soldiers during the Roman

invasion, and that the Roman evacuation occurred in 420, that would give 337

years as the period during which Victoria or Bertha was a Roman or Latin

town, governed by Roman laws and customs. It may have been, as is very

commonly asserted by antiquarians, one of the Roman cities of Britain.1 For

one thing, the native races had got from the Romans a military education, an

initial knowledge and experience of military tactics, and the use of arms.

In proof of this, they carried on warfare with redoubled vigour after the

Roman evacuation. Some writers go the length of saying that they drove the

Romans out of the country. Be that as it may, the life of the native races,

the Picts and Scots, for four and a half centuries afterwards, was one of

continued fighting, until in the ninth century, as already stated, they were

subdued by Kenneth M'Alpin, who became the head of the new monarchy. This

important achievement, which solved a great question, took place near Scone.

Kenneth was encamped there, and the Picts coming up under Drusken, their

king, both armies drew up in order of battle. The Picts were totally

defeated, and their king slain. What part Bertha played in this drama we do

not know, but there is reason to suppose it was the headquarters of the

Picts before the foundation of Abernethy and Scone.

It is not at all improbable

that the Ancient Capital occupied the site where Perth now stands. In

support of this theory, modern research indicates that the ancient town of

Agricola must have been 15 to 20 feet lower than the present town, and that

Perth of to-day is built over the ancient city. To protect the town against

inundations, the authorities were obliged to raise the levels from time to

time. During last century traces of buildings and paved streets, evidently

Roman remains, were actually discovered 15 feet below the present level in

the neighbourhood of St John's Church and St Paul's Church, the two

extremities, so to speak, of Northgate or High Street When the foundations

of St Paul's Church were being excavated, at a point where the surface is 20

feet above the level of the river, there was found at the depth of 10 feet a

work of well-built ashlar masonry, extending in a line parallel with the

river, and provided with iron rings and staples, indicating its having been

a quay. A subterranean stable was found under the present street level,

having four stalls and a manger very neatly wrought of the twigs of trees,

work that was much practised by the early inhabitants. According to an

ancient writer,1 such persons as had occasion to dig deep into the streets

found that there was a causeway many feet below the present surface.

Whittaker, a more eminent authority, is of opinion that Perth, or Victoria,

as it was called by the Romans, was declared to be a Latin town, the

privileges of which were that the inhabitants were not governed by a foreign

prefect and foreign questor, but by a prefect and questor elected by

themselves. Every inhabitant of such a town who had filled the office of

prefect and questor was immediately entitled to the privileges of a Roman

citizen. Assuming this statement to be accurate, Victoria or Perth must have

been in existence during the Roman period. The position chosen by Agricola

for his camp, if on the site where Perth now stands, would be an admirable

centre for military operations. It is recorded that the name given to it by

them was Victoria, signifying "Victory"; a name, however, which the native

races thought spelled "subjection." Accordingly, they changed it on the

departure of the Romans. To Agricola the name was suitable, as he had

conquered Britain, and the founding of a town would be a memorial to himself

and the senate and people of Rome. [The statement

by Chalmers that Victoria was in the west end of Strathearn is quite

erroneous.] The Bertha of Fordoun must have stood

on the site of modern Perth. He wrote in the fourteenth century. Boece, who

was born in Dundee in the fifteenth century, has been quoted by various

writers as an authentic historian. But he is not so, and cannot be accepted

as such, notwithstanding Adamson's belief in him. What Adamson has related

is not his own creation, but is understood to be conform to the current

literature of the time, and is, of course, open to question.

The Romans had many

encampments in Scotland, and not a few of these in Perthshire. The rivers,

mountains, and unexplored regions offered facilities for warlike operations,

and for the subjugation of the native races, while their campaign against

the Northern Picts evidently obliged them to make their initial preparations

in Perthshire as being a choice centre. There is no authority for the

statement that Agricola never was in the neighbourhood. It is sufficient

that he constructed a temporary bridge across the Tay at its junction with

the Almond, one mile up the river from Perth. This evidently was to enable

him to penetrate into the territory of the Northern Picts as after events

showed. It is said he exercised a vast influence for good amongst the Picts

and Scots, notwithstanding that he was engaged in subduing them, and that he

introduced Roman manners and customs, and stimulated the people to build

temples and improved dwellings. From what is recorded of Agricola, we should

think this a highly probable deduction. What gave rise to the town being

called Perth is not so clear. Evidently from Victoria it became Bertha. This

in all probability would be immediately after the Romans departed from

Britain. Up to 420 the town was evidently called Victoria, and was so

designated by the Romans. We have no charter or written documents so far

back to throw light on what would have been of much interest We must

therefore rely on the circumstances of the period, so far as known to us, in

order to determine these points. We assume, then, that Victoria was its name

when founded, and on the departure of the Romans the name was changed to

Bertha, and eventually Perth; as regards both these we must look for a

Celtic or Gaelic derivation. The origin of this place-name appears to be

found in "Aber-tha" meaning "the confluence of the river Tay," with

some other river or stream, or with the tidal waters. The initial vowel of "Aber,"

for the sake of abbreviation, having been thrown away, the name became

"Bertha," which being further curtailed became "Berth." The transition from

"Bertha," or "Berth," to the modern "Perth," is easy—B and P in the Celtic

vernacular being easily interchangeable; in fact, B in Gaelic is

invariably pronounced as if it were the softer consonant P. "Tay"

(Latin Tavus), and (Celtic Tarrh, pronounced "Tav"), means the still,

quiet, flowing water.Perth from the Roman period up

to the latter half of the sixth century was undoubtedly called Bertha, and

on the conversion of the Picts to Christianity was named St Johnstoun

because of the dedication of the Church to St John the Baptist Bertha does

not seem to have appeared in any official document Up to the seventeenth

century it was known both as St Johnstoun and Perth. St Johnstoun repeatedly

appears in official papers both before and after the Reformation.

Boece, followed by Camden, Buchanan and others, alleges

that the earlier "Perth" was at the confluence of the Almond and the Tay,

that its original name was Bertha, or Berth, and that the town

having been swept away by an abnormal flood, anno 1210, a new town arose two

miles farther down the river. This may be characterised as a fable, and

dismissed sans ceremonie. There was, however, a Rath-ver-Amon

at the head of the Almond, where Donald, brother of Kenneth M'Alpin,

according to the Chronicle in the Register of St. Andrews, died, anno 863,

and where Constantine IV. was slain, anno 995.

In the "Liber Ecclesiae de Scon" (especially in the

Charter given by Kings Alexander I., 1107-1124, Malcolm

IV., 1153-1165, and William I., 1165-1214), there is ample

documentary evidence that a town of the name of "Perth" was in existence

long before the year 1210; and where else but on the present site? Before

1210, it had its "castellum," its "mansio," its "molendina," its "pons," its

"villa," etc.

Boece, prior to 1200, is

careful to give it the name of Bertha, and after 1200 calls it Perth.

Fordoun gives it the name of Perth centuries before 1200. By the inundation

of 1210, according to the former writer, the King's infant son, nurse,

twelve women, and twenty servants perished. But according to Fordoun no

person perished in this inundation. There were many towns in different parts

of Britain when the Romans invaded it, not so much

for general residences, as for fortresses or places of refuge.1 Houses were

planted in the centre of forests, defended by the advantages of their

position, and secured by a regular rampart or fort. If there be a place

which bore that name (Malena) situated near Perth, from which the tide

rolled, and frequently occasioned a great overflowing of water, then it

seems to demonstrate that the town of Perth anciently stood on the same site

where it now stands.8 It appears from early records, that military walls to

resist sieges surrounded the Ancient Capital from a very early period up to

the middle of the eighteenth century. That these were originally built, as

some suppose, by Agricola, we think doubtful; nor do we think they were

built before the Romans left Scotland. On this point history is silent In

connection with these walls and fortifications, there were three of the

entrance gates to the town strongly guarded with towers—viz., the Speygate

or Southgate port, the nearest bridge port, and the south port or port for

Bridge of Earn. The fortifications were in the middle ages renewed and made

stronger by Edward III. Six monasteries were assessed for the cost of these

three gates and towers: the towers were built over the gates. The tower for

the building of which David Gow, prior of St. Andrews, levied 280 marks, is

supposed to have been the Spey, or Spy tower, which was built over the

Southgate of the town, near Canal Street

We are informed, on

sufficient authority,1 that Perth is intimately associated with the early

history of Scotland. For the first ten centuries of the Christian era, what

is now called Scotland was divided into petty kingdoms, and it was only at

the close of the tenth century that these were amalgamated, and formed the

kingdom of Scotland. The country was known previously by the name of

Caledonia or Alban. The geographical names-England and Scotland—had not then

been applied to the British Isles. North of the Forth the inhabitants were

called Caledonians or Northern Picts: south of the Forth, Southern Picts or

Britons. The territory forming the subsequent kingdom of Scotland was, in

the seventh century, peopled by four races: Picts, Scots, Angles, and

Britons, and a Roman historian, Marcellinus, who describes the first great

outbursts of the barbaric tribes upon the Roman province in Britain in 360,

says:—"Picti Saxonesque et Scoti et Allacoti Britannos aerum-nis vexavere

continuis." The Britons were the inhabitants of the Roman province, which

then extended to the Firths of Forth and Clyde, and was protected from the

barbaric tribes by the Roman wall between these two estuaries. Two and a

half centuries afterwards, all four nations occupied fixed settlements in

Britain, and had formed permanent kingdoms within its limits.

A well-informed writer says that the town was regularly

built and fortified at the command of Agricola while he was prosecuting his

conquests north of the Forth, and that he built a strong castle and supplied

the ditches with water by an aqueduct from the Almond In the sixth century

the Picts were converted to Christianity, and dedicated the Church of Perth

to St John the Baptist This is the earliest historical incident recorded,

and it enables us to recognise the fact that Perth was at that period a town

of moderate size, at a time that might be called prehistoric. The matter of

the alleged exclamation of the Roman soldiers when they first beheld the

Tay, "Ecce Tiber, Ecce Campus Martius," is nothing more than a

tradition. The new statistical account states that Adamson, who recorded it,

had in his possession the Dundee MS. From what Cant says, it contained

nothing about "Ecce Tiber." Dundee was a citizen of Perth, and in

this MS. were recorded several local events. The MS., which has

unfortunately been lost, dates from 1570. Up to the time of Columba, the

primitive dwellings of the inhabitants would not necessarily be of stone.

They are more likely to have been of wood and wattles, and for some

centuries that would probably be the class of house forming the town.

We are further informed that if the authority of ancient

writers is to be accepted, there was a town built on the site of Perth by

the Romans in the first century. Historians have preserved some notice of

the existence of Perth during the troublous centuries that preceded the

reign of Malcolm Canmore. Before David I. came to reign, according to these

authorities, there was regular government in Perth, under which people lived

and had a measure of protection for their property. The King, residing in

the old Castle of Perth, took an interest in the town's welfare, called it

"his burgh," and threw the special protection of law around its inhabitants

; he granted them the privileges of free citizens, with right to elect

magistrates and administer justice, and conferred a monopoly

of trade within the county of Perth. Like other royal burghs, there

were an Alderman or Provost, Bailies, and Council, elected annually at

Michaelmas, by the free voice of the burgesses in public assembly. Under

David I. the rights and privileges of the burgh were the common property of

all burgesses, whether craftsmen or merchants.

It is stated by another writer that early in the fifth

century, about 422, a Roman legion made its appearance for the last time,

and succeeded in driving the Picts beyond the northern wall; but it was no

longer possible to retain the province of Valentia—the country between the

walls of Antoninus and Severus. During their occupation, civil war was

constant between them and the Picts and Scots. For a century and a half

thereafter, there are practically no annals at all, so that we know nothing

of the country for that period. For a time after the Roman occupation

ceased, a darkness, it is said,1 settled down over Britain and shrouded the

inhabitants from the eye of Europe, till the spread of that great and

paramount influence which succeeded to the dominion of the Roman Empire—the

Christian Church.

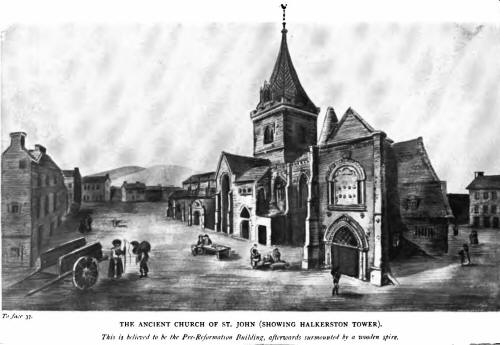

Perth stands supremely alone,

as being probably the scene of more historical events and as having once

been distinguished by more ancient monuments than any place of which we are

aware. The latter, if we except the Church of St John, have all passed away.

Some were monuments of no mean pretensions. There was the House of the

Green, the most ancient of them all, with its predecessor the Pagan temple

dedicated to Mars, and its legendary reputation; the Gilten Herbar or Gilten

Arbor, with equipments in gold, silver, and brass, forming part of the

grounds of the Blackfriars; the Castle of Perth, the residence of the early

kings, with its garden and its constant influx of royal personages; Gowrie

House, which for elegant design and internal equipment was a famous

building; and the Carthusian Monastery or Chartreuse, the most ornate and

elegant of them all. These monuments will continue to have a deep interest

to natives of the ancient capital, as well as to students of Scottish

history, for they will always throw a side-light on the chess board of local

events at a time when few historical records were written. But when all has

been said and done, we much regret that so little has been recorded, and how

little we know of the social and political life of the inhabitants all

through these ages since the Roman period. The greatest event in Agricola's

campaign was probably his defeat of Galgacus, although it is a fair

deduction to suppose that he must have fought several battles, looking to

the number, extent, and vast distance between the Roman camps in Scotland.

Tacitus gives us the details of one battle, but he does not say that that

was the only one that was fought by Agricola. He has left us entirely in the

dark as to where Mons Grampius is, where this battle was fought. Much

controversy has taken place over this event, and whether it was fought in

the district of Comrie, as some allege, or at Blairgowrie, or near

Stonehaven, it is impossible now to determine with certainty. Excavations

have recently been going on at Inchtuthill, on the Delvine estate, and

military weapons have been found there which seem to indicate that a battle,

but not this battle, must have been fought in that neighbourhood. Agricola

evidently pursued the enemy along the ridge of the Grampians, probably to

Inchtuthill, where he crossed the Tay by a wooden bridge. There are Roman

remains all along the ridge. The Roman road from Innerpeffray to Dupplin

seems to have been made at more leisure, when the Romans were settled in

Angus, as all the country to the east of the Tay was then called. That these

roads were not completed, not even the bridges over the Tay and Isla, seems

evident, as the Romans retired by the wooden bridge at Inchtuthill, and

broke it down after them, which obliged the Scots to march to Dunkeld and

erect a wooden bridge there.

Some writers point out that at the date of the battle the

word "Grampians" had not been applied to these mountains, nor was it applied

for long after, Drumalbyn and the Month or Mounth being the names by which

these hills were then known. Consequently, there are those who deny that the

Mons Grampius of Tacitus had anything to do with the Grampian mountains.

Instead of the Roman author taking the name of the battlefield from the

native name of a chain of hills, we have given the chain of hills its name

from that by which the Roman author was supposed to have designed the

battlefield. We find there are vestiges of Roman camps at Camelon, Ardoch,

Strageath, Bertha, and Coupar-Angus. At Callander (Leny) the camp was very

extensive, and the ramparts of great height and strength. At Dalginross and

Glenalmond there were only summer camps of small extent.

From the neighbourhood of Perth all through Strathmore,

Roman works are to be found, and in the Muir of Lour in Forfarshire are to

be seen the remains of two Roman camps, with a causeway or Roman road

running between them (eight miles). The camp at Battledykes, three miles

north of Forfar, is defended on all sides by two ramparts of stone and

earth, and two gates on the north and south sides. It is no paces in

circumference;1 another writer says it is 470 yards square. Another camp in

the Muir of Lour at Haerfaulds, said to be 800 yards in length and 400 in

breadth, is about eight miles from that at Battledykes. Those two camps,

thus connected, secured the whole breadth of the valley of Angus.

Battledykes is six miles from the nearest mountain, while Haerfaulds is

eight miles from the sea and guarded the other side of the valley. The

military way from Fordoun must have gone by the large camp at Ury hill,

three miles north-west from Stonehaven. This camp (Kempstonehill) is

three-quarters of a mile square and three miles in circumference, fenced

with a high rampart and a very deep and broad ditch. There are six gates,

each fortified with a rampart and ditch. Another writer supposes the Romans

to have proceeded through Strathmore and the "Howe" of the Mearns to

Fetteresso, where there are the remains of a Roman camp, situated about a

mile from Stonehaven and not far from the sea. From this camp the Romans,

according to this writer, proceeded north-east along the coast, crossing the

water of Cowie (which runs past Ury) to the Kempstonehill, a few miles north

of Stonehaven, where there are three cairns. These are between two huge

stones, each 10 feet high, standing on end, 100 yards from each other. In

each of these cairns stone coffins have been found, within which were urns

containing earth.

It is probable that Agricola

first visited his fleet at the mouth of the Tay; then marched to the Muir of

Lour, thence to Battledykes, and onward to Stonehaven, where it would seem (Kempstonehill)

the great battle described by Tacitus was fought.There is much probability

in the theory laid down by this writer, and much to be said in support of

it, although we cannot regard his conclusions as final.

In regard to the camp at Dalginross another writer wrote

an interesting and well-thought-out paper in 1807, which was read before the

Perth Literary and Antiquarian Society. He says tradition reports that the

battle lasted three days between Edinample, Lochearnside and Cultoquhey. He

adopts Gordon's idea that the battle took place on the plain at Dalginross,

which is four miles long from the wood of Craigish to nearly opposite the

church of Strowan, and in most places one and a half miles broad. He refers

to the hills from Aberuchill to Monzie as forming a great amphitheatre, and

as fitting in with the description of Tacitus, and etymologically from

Gaelic derivations conveying the same meaning as the word "Grampians."

Whittaker uses the same argument for the battle having

taken place at the confluence of the Tay and Isla. That is on the estate of

Ardblair, the Gaelic derivation of which is, he says, the Hill of Battle. It

is thus obvious that the exact site of the famous engagement cannot be

accurately determined. For Kempstonehill, Dalginross, and Inchtuthill

respectively much is to be said, and the solution of the question must for

ever lie between these places whose claims to the honour are decidedly

strong.

The balance of evidence inclines us to favour

Kempstonehill. The Roman works there and in all that neighbourhood are of

such an extensive character as to arrest our attention in the consideration

of this matter. There is no other locality in Scotland, so far as we are

aware, where such huge encampments were built and fortified. These works

were presumably executed in view of permanent occupation, as the subjugation

of the Caledonians or Northern Picts was a work that might last for years.

Those warlike people, like the Boers of the Transvaal, fled into the

fastnesses of their wild surroundings—into the caves and covers of the

rugged mountains, in the face of an enemy. To get at them was an operation

of no small difficulty. The elaborate preparations for the subjugation of

the country which these camps indicate are a strong proof that the Galgacus

engagement took place there.

The Romans founded various towns in Scotland at that

period, although we have no historic record. The Emperor Vespasian,

Agricola's friend and patron, died in A.D. 79, and was succeeded by Titus,

his eldest son, who in the third year of his reign died from the effects of

poison, said to have been administered by Domitian, his brother. In the

second year of his reign Domitian recalled Agricola. Shortly after this

Agricola died in his fifty-sixth year, of poison, also said to have been

administered by the tyrant Domitian. A beautiful tribute was paid to his

memory by Tacitus, his son-in-law: "All of Agricola that gained our love and

raised our admiration, still subsists and will ever subsist, preserved in

the minds of man, the registers of ages, and the records of fame. Agricola,

delineated with truth, and fairly consigned to posterity, will survive

himself and triumph over the injuries of time."

Strange though it may seem, we find that the Ancient

Capital or its immediate neighbourhood was in early times the seat of an

encampment of the Druids. This encampment was at Kilspindie, a few miles

distant. Of these people we know very little, while a great deal that has

been written about them is the merest conjecture. One thing is certain, they

were a cruel, barbarous, and despotic race, indulging in the most abhorrent

of all rites, the sacrifice of human beings.

Religion, prior to the time of the Culdees, was in the

hands of the Druids, who are supposed to have combined the characters of

prophet and priest Religious rites are said to have been celebrated by them

in the recesses of the forests, which at that time covered a large part of

the country. The Druids had no covered temples. The forest was their temple,

and a rough unhewn stone their altar. They worshipped deities corresponding

to Jupiter, Mars, and Apollo, and were ruled by an elected chief. They made

their own laws, which they never reduced to writing, and constituted

themselves the instructors of youth and judges of the people. Whether they

taught the immortality of the soul and its transmigration from one body to

another until received into the assembly of the gods, as has been said by

some writers, may or may not be true. The Druids are believed, in the

legendary traditions of the Highlands, to have been of both sexes, as we

also learn from the testimony of ancient history. When Suetonius invaded the

island of Anglesea, his soldiers were struck with terror at the strange

appearance of a great number of the consecrated females, who ran up and down

the ranks of the army like enraged furies, with their hair dishevelled and

flaming torches in their hands, imprecating the wrath of Heaven on the

invaders of their country. These Druidesses were of three classes—those who

vowed perpetual virginity; those who were married, and those who served. The

Druids computed time by nights not by days, and they regulated all their

great ceremonies by the age and aspect of the moon. Their most august

ceremony of cutting the misletoe was always performed on the sixth day of

the moon.8 Whatever they may have been in Caesar's day, they were supposed

to be endowed with gifts of divination and a certain limited power to work

miracles—something partaking of the witch and Bohemian in later times. They

were the supreme judges in all disputes, and ratified their decisions by

excommunication.

On the testimony of Caesar,

all the Druids were subject to an Arch-druid. In Caesar's time the chief

school of the Druids was said to be in Britain, and he therefore infers that

Druidism was unveiled in Britain and thence translated to Gaul. The Druid

temple consisted of one circle of erect stones. In the centre stood an erect

stone larger than any of the rest Near this, and generally due east of it,

lay an oblong flat stone, which served the purpose of an altar. On the north

point, which was the door of entry, stood a vessel filled with water, with

which every one who entered was sprinkled. The judicial circle, in the

exterior, differed in nothing from the temple; in the interior it differed

widely. It had no obelisk in the centre, no altar, no sprinkling vessel. It

contained one, two, or three divisions; the three circles being intended to

accommodate the three ranks of Druids, nobility and commons.1 The largest

Druid temple now remaining is at Carnac in France, where the circle numbers

400 stones. The next largest is Stonehenge, the circle there numbering 139

stones, while the one at Avebury in Wilts covers a space of 28 acres. The

next largest is that at Callernish, in the Hebrides. Few people are aware

that the Druids had a very close connection with Perthshire. An interesting

paper on the Perthshire encampment in the Carse of Gowrie was read nearly

100 years ago by Archibald Gorrie of Rait before the Literary and

Antiquarian Society of Perth. It is rather a remarkable paper, and affords

information on a subject of great obscurity. The substance of it is as

follows:—

The Druids are said to have

been acquainted with the learned languages, skilled in the philosophy of the

times, and to have possessed much political influence, and to have been the

leaders of the people in theological matters. It is said they honoured the

Divine Being, and worshipped inferior deities, that they believed the soul

to be immortal, but that it passed from one body to another; that they had

consecrated fires, and that they either worshipped fire or adored the Deity

in the presence of the fire. They worshipped in groves, and erected circles

of large stones, where they performed religious rites and held courts of

justice. That the Druids came from Asia at a very early period is beyond

doubt, and that they retained many of the religious ceremonies practised by

the heathen nations there is quite evident The heathen deity Baal was an

object of veneration among them. The high places of Baal are to be met with

in this county, and still retain the name of that god to whom the Druids

paid homage. The hill of Beal (Baal) is situated in the parish of Kilspindie,

and forms the most conspicuous eminence in that part of the Sidlaws. On the

summit of this hill is a level area capable of accommodating 5,000 men. Here

the Druids are supposed to have held their annual assemblies, and from the

extensive view could issue signals to light the hallowed fires all over the

surrounding country. A circle of stones has given the name of Clachan to a

small eminence about 200 yards east from the hill of Baal. A mile to the

east is a perpendicular rock called Craig Greine or Craig of the Sun.

Some suppose that the Sun was worshipped under the name of Baal. To the east

of Craig Greine is a circle of stones, and in one of these are

several cavities to receive the water pure as it fell from heaven, and in

which the Druids are said to have performed their ablutions. About a mile

south from this is another circle of stones, while at Bandirran, three miles

from the hill of Beal, stands another circle. The adjoining ground is Dritch

Muir (Druids' Muir). On breaking up some of the ground in 1819, a large

cairn was discovered, coated over with turf a foot in thickness. Below the

cairn and about the centre of the circle was a pit 30 feet long by 18 feet

deep, faced on the sides with freestone and paved in the bottom. It was

empty. But a number of small cairns which were found near it, covered large

quantities of ashes; and human bones, half burnt, were found amongst the

stones, indicating that the Druids offered human sacrifices, or used the

ground as a place of sepulture. Two miles from Druids' Muir is a place

called Sildry, supposed to have taken its name from its summit having been

used as an observatory of the Druids. About a mile south from the hill of

Beal is a stone circle called the Druids' Temple. The church of Kilspindie

stands a short distance south-east from that circle. Near the church is the

village of Pitroddie—Pit-drodie, Pit-Druidae—the burying-place of the

Druids. On a rising ground near the village a number of ancient graves were

found—some below large cairns, others almost at the surface. From the top of

the hill is to be seen Tullybelton (in Gaelic, Tulloch-Beal-tein, mount of

Baal's fire), also Drumbeltie (Caputh), Drum-Beal-tein. These were resorts

of the Druids.

The most vigorous opponents of the early Celtic

missionaries were the Druids. The Druids are presented to us as sorcerers

and magicians. Their stone circles and cromlechs are not heathen temples and

altars, but sepulchral monuments. The magi of the Columban period are not

priests, but wizards who have gained control over the powers that underlie

the forces of Nature.

In Kirkmichael parish, Perthshire, is a vast body of

Druid remains. On an extensive moor in the east side of Strathardle, there

is a large circle or heap of stones 90 yards in circumference and 25 feet

high. From the east side of this circle two parallel rows of stones extend

to the southward in a straight line upwards of 100 yards. These form an

avenue 32 feet broad leading to the circle. West from this are two

concentric circles of upright stones, the outer 50 feet, and the inner 32

feet in diameter, and in the vicinity is a rocking stone. About 60 yards

north of this are two rude concentric circles similar to the others, and 37

yards farther on another pair of these circles. From these, at a distance of

45 yards, there is another pair, while in the vicinity are two rectangular

enclosures of 37 feet by 12. All the concentric circles are of the same

dimensions, the inner 32 and the outer 45 feet in diameter.

In regard to the early inhabitants of Perth, the question

has been often asked, Who were the Picts? Dr. John Stuart, an eminent

antiquarian, informs us that it was the custom of the Britons to stain their

bodies before the Roman occupation. Herodian, who lived in the third

century, says they punctured their bodies with pictured forms of every sort

of animal; and Thomas Innes, in 1729, makes it plain, while speaking of the

ancient inhabitants, that the southern Britons, having given up the custom,

the term "Picti," the painted, came to be applied to those in the north who

continued the practice towards the end of the third century. A work called

the "Historia Britonum," written in the seventh or eighth century, says:

"From their tattooing their fair skin they were called Picts."

The appearance, therefore, which our forefathers

presented to the Romans must have been similar to that which the natives of

New Zealand presented to the Europeans who first landed amongst them.

The Picts, who are said to have occupied Scotland 200

years B.C., were a warlike, not a learned or literary people. The only books

written in Scotland up to the seventh century are said to have been the

lives of Columba and Adamnan and their writings, and the Chronicles of the

Picts and Scots. Books were written in these days by the monks, and up to

the eleventh century on papyrus imported from Egypt Paper made from silk and

cotton was an invention of the eleventh century, and common paper as we have

it of the fourteenth century. The services of the Church were performed in

Latin, and it was considered an act of piety to attend, though scarcely one

of the audience understood a word. The Picts had their own language, and did

not understand Latin. It would thus appear that the service in St John's

Church was in early times conducted in Latin. The English language of to-day

was then unknown to the people. Latin was the official language recognised

on all public occasions, and by the monks and scribes in reducing anything

to writing. Latin continued to be so for centuries, alongside of the native

dialects, the Pictish, ancient Scots, and Gaelic or Celtic.

The introduction of Christianity into Britain and its

early connection with Perth forms an important chapter in our local history.

Tertullian informs us that the Gospel had made its way into parts of Britain

which the Romans had never reached, and he adds "a statement which may be

supposed to indicate that at the end of the second century even Scotland had

not been unvisited by missionaries." The churches of the early Christians

are stated to have had no images or pictures. The connection of art with

heathen worship operated against the employment of it in sacred things. Up

to this time the figure of the Cross had not assumed its place in Scotland

over the altar, nor was any devotion paid to it2 The more prominent events

of the second and third centuries were the persecution of the early

Christians by the Roman emperors, and controversies by persons having false

notions of Christianity desiring to form peculiar sects of their own. In the

beginning of the fourth century came the Arian heresy, combated by

Athanasius, who fought many a battle on behalf of orthodox Christianity.

The middle of the fifth

century is remarkable as the period of the fall of what was known as the

Western Empire. The Roman Empire was beginning to give way—the Western

Empire being one of its dependencies. Britain, France, and Spain had been

already abandoned by the Romans. Whether their leaving Britain was an act of

expulsion by the Picts, or whether they found themselves unable to spare the

forces necessary for maintaining a military establishment here, is not very

clear.

The next historical event was

the arrival in Scotland in 563 of St Columba with twelve companions. For

thirty years he laboured at Iona, where he established a little college long

famous as a centre of religious training. The life and habits of Columba and

his followers were characterised, as is well known, by self-denial. The

rules laid down by the venerable saint were not to be disobeyed Six strokes

were to be given to any one who would call anything his own; ditto to any

one who should omit "Amen" after the abbot's blessing, or to make the sign

of the Cross on his spoon or his candle; ditto to every one who should talk

at meals or who should fail to repress a cough at the beginning of a psalm.

Ten strokes for striking the table with a knife or for spilling beer on it.

Penitents were not allowed to wash their hands except on Sunday. Such, we

are informed, is an illustration of Columba's rigid discipline.

A statement of considerable importance is made by

Jamieson that Columba went into the eastern parts of Scotland or the

territories of the Picts, and also was the means of converting Brude, the

Pictish King, whose reign terminated in 587. When Columba and his companions

arrived at the palace of King Brude, they were met by closed doors; but

before the sign of the Cross, as the story is told, the locks flew back, the

gates opened, and Columba and his companions entered. At the time of this

visit Inverness was the Pictish capital. Abernethy and Scone were

subsequently capitals. The visit to Brude is believed to have lasted some

weeks, and to have resulted in his conversion and consequently the

conversion of the Pictish people. His leaving the north was attended with a

curious incident. On his announcing on what day he was to depart, a powerful

Druid called Broichan intimated that on that day he could not leave, as he

would raise a contrary wind and bring down the mist from the mountains; and

so it happened. But Columba embarked in spite of the murmurs of the sailors,

and ordered his canvas to be spread in the teeth of the gale and sailed

triumphantly against the wind. This highly important visit with its results

was the greatest event of the time, although it is unfortunate that we have

no details of it. While it would be fully recorded afterwards by the monks,

we must remember that the civil war and fire-raising which prevailed in

these early centuries, the partial destruction of Perth by the flood of

1210, the various sieges of Perth, and the seizing of the national records

by Cromwell, are sufficient to account for the disappearance of our

historical MSS., which unquestionably perished during these troublous times.

In those prehistoric days Columba was like a ministering angel, heralding

the dawn of Christianity which, in subsequent ages, was to be the means of

civilising the native races and securing to the kingdom the peace and

prosperity we now enjoy. In view of this remarkable event, and of the

pilgrimage of Columba to other parts of Scotland, a statement which has not

been called in question, it is reasonable to conclude that Columba, in the

course of these wanderings, visited Perth and preached the gospel to the

Picts. What lends probability to this is that we know the conversion of the

Picts followed as the result of his visit to the Pictish king. Perth at that

period was a Pictish town, though not the capital, and was one of the places

where the Northern Picts had a Pagan temple. It is fair to conclude from the

circumstances of the time, and the fragmentary knowledge we possess, that

the mission of Columba resulted in the abolition of this Pagan temple,

afterwards replaced by the House of the Green, and the erection of the first

Christian Church by the Northern Picts—afterwards called the Church of St

John. The dawn of Christianity was thus heralded by the great apostle of

Iona, and Perth of that day, with its primitive little Church, may be said

(exclusive of St. Ninian's Mission) to have witnessed the first rays of

Christianity that dawned upon our island. Had the loss of the national MSS.

not occurred, we should doubtless have been able to confirm from authentic

evidence the visit of Columba to Perth, and his opening the first Christian

Church in our midst—the church which has lived through all these ages, and

which we are proud to have still preserved as the greatest ornament of the

Ancient Capital.

While Perth has had a remarkable history, and been

identified with sieges, battles, floods, conspiracies, the Reformation and

the two Rebellions, the visit of Columba and the conversion of the Picts in

563 must ever be pre-eminent in importance as an historical incident, while

it stamps our local history with the' mark of antiquity, and gives to our

city a strong claim to be regarded as quite as ancient as any other town in

Scotland. It is well entitled to the appellation of the Ancient Capital, and

the narrative which follows will disclose a singular record, mixed up with

many startling events both in its civil and military administration, in all

of which the Scottish Parliament, the Scottish Nobles, and the Estates of

the Realm played a conspicuous part We are informed by a highly capable

authority, that Perth is certainly a place of very high antiquity. No record

or chronicler alludes to its origin. It is probably as old as any sort of

civilised society among us.

The nature and administration of the Columban Church,

like many historical questions, has been surrounded with controversy. The

three great bodies, the Presbyterian, Episcopal, and Roman Catholic, each

claim it as having been administered according to their formulas; while a

learned writer, in our own time, says the constitution, as a whole, of the

Columban Church, in which all bishops in the Church's service were under the

supreme jurisdiction of the presbytery and abbot of Iona (Bede, iii.), is

quite inconsistent with what is, and then was, a leading feature of the

Roman Church, viz., the government of the Church by an Episcopal Hierarchy.

Another writer, who cannot be disregarded, tells us that Iona had a rector,

and always an abbot and presbyter, to whom all the province and the bishops

themselves were subject Segenius was presbyter and abbot of Iona when Aidan

got the degree of a bishop, and was sent in 633 to instruct the province of

the English. Bede informs us that Iona had a governor who was abbot, and

always a presbyter to whose jurisdiction all the province and even the

bishops themselves ought to be subject, according to the example of their

first doctor, who was not a bishop, but a presbyter and monk.

The Scottish or Columban

Church, according to some writers, was at first governed by bishops, clothed

with the same powers and authority that their contemporary bishops in other

parts of the Christian world exercised. Neither, as one writer says, from

the manner of our first conversion to Christianity, nor from the practices

and settlement of the Culdees, nor yet from the constitution of the

monastery of Iona, can it be gathered that the first model of a church among

us was founded in any other way than what was conformable to the then custom

of the Christian Church all the world over, and that was by the government

of bishops as distinct from, and superior to, presbytery. This writer speaks

of the government of bishops "as the custom of the Christian Church all the

world over." This is very misleading, as at that period we have no proof of

uniformity of government in the Christian Church. It was simply beset with

controversy regarding both its doctrine and government

It is extremely probable, if

not certain, that Columba, who cannot be proved to have had any connection

with Rome, notwithstanding the persistent and ingenious statements of some

writers, formulated his own rules for the government of the Church which he

founded. We must bear in mind that the Episcopal Church was not in existence

at that date. It was founded at Canterbury in 595, after Columba's time, and

was at that period in full communion with the Church of Rome. The Celtic

Church of Columba was a missionary church, not a diocesan but monastic, with

an abbot, who was a presbyter (not a bishop), for its head. . . . Most of

his time was devoted to the administration of the monastery at Iona, and to

the planting of other churches and religious houses in the neighbouring

isles and mainland.1

Bede, who wrote in the eighth century, says: "In the year

634, when Segenius was abbot, Aidan was consecrated at Iona, and sent to be

bishop of Holy Island." He was succeeded there by Fernen and others, all

clothed with the Episcopal character, and receiving that character from the

monastery of Iona. At Iona there was always a resident bishop for exercising

the Episcopal function. Bede was educated at Rome, and in England, when he

returned, was made a bishop. Chalmers, in his turn, informs us that Columba

and his disciples travelled for purposes of instruction through every part

of the British territories. They established monasteries in every district

of Caledonian territory.

The Columban Church was in reality a mission from the

Irish Church, forming an integral part of that Church, with which it never

lost its connection. We ought not to expect that in character it differed

materially from that Church. It was essentially a monastic Church without

territorial Episcopacy or Presbyterian parity. Its doctrines in no respect

differed from those of the Church in Ireland. The Columban Church according

to Columbanus received nought but the doctrine of the Evangelists and

Apostles. Whether it was governed by a bishop is a question that will

probably never be finally determined. So far as we can discover, we don't

think it was.

Columba seems to have been mainly engaged in spreading

the truth among the Pictish tribes for nine years after the conversion of

King Brude, when he appears to have at length attained the primary object of

his mission and visited Glenurquhart and Skye. King Brude died in 584, and

his successor in the Pictish throne, Gartnaidh, had his royal residence at

Abernethy, in the neighbourhood of Perth. He built the Church of Abernethy.

He was called the Supreme King of the Tay, and of the tribes above the Tay,

the people whom Columba taught For some months in the latter part of his

life he was resident in Ireland. Of the monasteries which were founded in

the Pictish territories by Columba, Adamnan gives us no account, nor does he

mention any by name. The Book of Deer shows that these foundations extended

as far as the Eastern Seas. (This would include Perth.) A few of Columba's

other foundations in western districts and islands can be traced by their

dedication to him. Adamnan tells us that he founded monasteries within the

territories both of the Picts and Scots, and that he was the head of the

Christian Church in Scotland.

The Abbacies of Dull and Glendochart were founded in the

seventh century, and their territory comprised the entire districts of

Atholl, Strathearn, Madderty, and Crieff. The Monastery of Dull becoming

secularised in the time of Abbot Crinan, the possessions descended to the

Royal line, but were gradually broken up. Glenlyon, Fortingall, and Rannoch

had all the parts of the Abthanerie. In 1455 the gross rental of Glenlyon

was £33 6s. 8d.; of Fortingall, £16; of Rannoch, £18 6s. 8d.; of Methven (Strathearn),

£120 8s. 4d. The accounts of 1373 inform us that the rents of Dull

had been uplifted by Alexander Stewart, the "Wolf of Badenoch." Kinclaven,

near Perth, was in early times Crown property, with a castle alluded to in

the Exchequer Accounts of the reign of Alexander II.

It was granted by Robert II. in 1383 to

John Stewart, his illegitimate son. At what date it again reverted to the

Crown does not appear.

In the seventh and eighth centuries the Scottish people

used chariots, and manufactured swords and other weapons, probably those

articles of bronze so commonly dug up in the west of Scotland. They used

cloaks of variegated colours, of home manufacture; and fine linen, which

must have been of foreign production. The bodies of the dead of high rank

were wrapped in it In the earliest churches there were bells, but only hand

bells. They had boats or coracles of leather in the rivers, and galleys

built of oak and carrying sail.

In 802 Iona, which is said to have been presented to

Columba by the Picts, was burned by the Danes, and the little community,

numbering sixty-four monks, brutally slain. This catastrophe led to a

resolution to remove to a safer locality, and Dunkeld was fixed on as the

new site. The first church there was founded by Constantine

II., King of the Picts, in 814, or twelve years

after the burning of Iona and fully two centuries after the foundation of

Abernethy, which is recorded as in 588.

The geology of Perth offers some remarkable features to a

student of science. It would appear from a well-informed local writer that

Kinnoull Hill had at one period been connected with the Hill of St

Magdalene, and that the disjunction which now exists has been gradually

effected by the operation of water and other natural causes. Large masses of

conglomerate completely detached from other rocks are to be found in the bed

of the Tay between Orchardneuk and Friarton, the very position which they

ought to occupy had a process of disintegration taken place. Without that

supposition no satisfactory hypothesis can explain how these rocks came to

occupy their present situation. The subsoil in every direction round Perth

exhibits the most undoubted evidence that it had been exposed to the action

of water. Much of it consisting of gravel, sand, etc, could only have been

reduced to its present state by water. In many places the remains of trees

and other vegetable productions have been found at a great depth below its

surface, but probably 20 or 30 feet above the level of the Tay. Of this fact

we have an example at Friarton, where trunks of large trees have been seen

to protrude from the bed of clay which there forms the bank of the river. A

careful examination of the superincumbent soil leaves no doubt that it had

been deposited over the organic remains which it envelops by the action of

water, a fact which is sufficient to prove that the Tay must at one period

have been at least 30 feet higher than its present level. A barrier of 300

feet high running across the river between the hills of Kinnoull and St

Magdalene would have been sufficient to cause the waters of the lake, to

which they gave birth, to flow down the valley of Strathmore and discharge

into the sea at Lunan Bay. It is a curious fact that we find along the

route, which the waters of the Tay must have pursued, the remains of a great

river in a chain of lochs which stretch between Forfar and the point at the

coast which is its probable embouchure, while in the intermediate districts

lying between these lochs there is abundance of gravel and other water-worn

materials to attest the former operations of a river.