|

EARLY FARM IMPLEMENTS—TEN SICKLE OR REAPING HOOK

SOWING THE GRAIN - CRADLING GRAIN - THE

REAPING MACHINE—SHEEP WASHING AND SMEARING.

ALL the farm implements in the early days

were made by hand, the wooden part being

made by the farmer himself, and the iron part by

the wayside blacksmith, although some of the farmers had forges of their

own and were ingenious enough to do their own blacksmithing. The

implements used by the pioneers were few and simple compared with those

used by the farmers of the present day. The chief farming implements were

the plough, harrow, cradle, sickle, rake, scythe and roller.

Many improvements have been made in the plough of recent years. The first

plough was made of wood (usually a piece of bent oak), and covered with

iron. Some very rude ones were made out of a natural crook, as the root of

a tree; others had wooden mould boards and iron points.

The first harrow used in the backwoods clearings was

the "three-cornered drag," a V-shaped framework of wood, with cross-pieces

and fitted with iron teeth. It was often made out of the crotch of a tree,

holes being bored for the iron teeth. This kind of harrow was particularly

well adapted for working up the soil in the stumpy ground, as, on account

of its shape, it did not catch on to the stumps so easily as the square

harrow.

The "brush" or "bush" harrow, made of a bunch of

brushwood, was sometimes made to answer the purpose of a harrow in the

loose soil of the new ground, which very often did not require any

ploughing at all the first time cropped. In the cleared ground, the square

harrows, made of wood with iron teeth, were used. These were afterwards

made in two parts and hinged together. This kind of harrow has been almost

entirely superseded by the harrow made of steel.

The only kind of rake was the wooden hand-rake; later

on, the wooden lift-rake, and the wooden dump- rake, drawn by a horse,

came into existence. The farmer walked behind and held the handles until

sufficient hay had been collected, when he would lift or dump it in rows.

These rake3 were followed by the sulky-rake now in use.

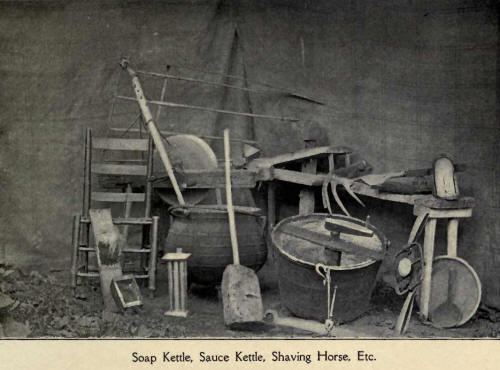

For levelling off the lumpy ground the farmer had a

roller, made out of a heavy log of wood, with a tongue attached to it, to

hitch the horses to. The minor farm implements were the long-handled

shovel and spade and the pitchfork, the hoe and garden rake, all very

heavy and clumsily made of iron, while nowadays such implements are made

of steel, and consequently much lighter and better finished. There were

wooden forks for pitching straw. The manure forks were generally made with

broad tines and very heavy.

The old farm wagon had wooden axles with a strip of

iron above and below, to prevent the wood from wearing away. They were

greased with tar, made from the pitch got from' the pine trees, and mixed

with lard in the winter time, to prevent it from becoming too thick. The

tar was kept for the purpose in a special bucket, which was hung

underneath the back of the wagon when on a long journey.

The wheels of the old "lumber" wagon were kept in place

by linch-pins, which were dropped through a hole in the end of the axle,

but as they did not secure the wheel very tightly when the wagon was in

motion, they made a rattling noise, which could be heard for quite a

distance away. There being no iron wagon springs, the seat was perched on

the end of two poles with the ends fastened in the wagon box. This

"spring-pole" wagon-seat, although high up in the air, was the most

comfortable one known.

The Sickle and Reaping Hook.

In the early days of the country all the grain was cut by means of the

sickle, a curved knife a couple of feet long, with indented teeth. This

was the only kind of harvest instrument the farmer had for years for

cutting grain, the cradle being then unknown. To cut a field of grain with

it must have been a slow and tedious as well as a very tiring process.

With all hands on the farm to help, however, both male and female, the

harvesting was soon accomplished. It is interesting to hear some of the

old folks tell how first the grain was sown, cut, threshed and got ready

for the mill. It was frequently planted in the stumpy ground with a hoe or

rake. When ripe it was cut with the sickle, bound in sheaves, and taken on

the jumper to the threshing-floor, which was often no better than a big

flat stone, sometimes a floor of boards, and sometimes even the bare

ground, tramped hard and smooth, where, by means of the flail, or

"poverty-stick" (two pieces of hardwood united by leather), the heads were

pounded until the grain was all threshed out. It was then "winnowed," or

cleaned, by pouring from one vessel to another in the

wind, until it was free of the chaff, after which several bags were put

across a horse's back and sent to the mill—often fourteen or fifteen miles

or more distant—to be ground into flour, the farmer having to wait

patiently his turn for this to be done, and which sometimes kept him from

home for several days together. It was not an uncommon thing for some of

the old settlers who had no horses to have to carry the bags of wheat to

the mill on their backs for long distances of fifteen or twenty miles. The

first mills were situated on some stream or creek, where water-power could

be obtained, as there were, of course, no steam mills then in the country.

These water-power mills were scarce, even, people sometimes going forty

and fifty miles to get their grists ground hand mills for grinding wheat

were furnished by the Government to the U. E. Loyalists, and those who did

not have these hand-mills would burn a hole in the top of a white oak

stump; into this hollow, when well scraped out, they would place the wheat

or corn and grind it into a coarse meal with a pestle made out of a piece

of hard wood. This was probably in imitation of the Indian method of

grinding their corn in stone cups or bowls. To facilitate the operation

the pestle was sometimes fastened to the end of a spring pole extended

over a forked stick stuck in the ground. The first crop of the settlers

usually consisted of a field of wheat and peas, with a small patch of

potatoes, pumpkins and corn.

Sowing the Grain.

Formerly the farmer in sowing his grain had a sack tied

around his body and as he walked over the ground he scattered the seed

with a sweep of his hand. With measured step he strode forward and did his

work carefully and manfully. This method of sowing grain was common for

centuries. Our Saviour speaks of it in His parable of the sower. Since the

seed drills were introduced, forty or fifty years ago, the old-fashioned

way of sowing has gradually been discarded, until now there is scarcely a

farm that is not equipped with a seed drill.

Cradling Grain.

Following the sickle came the cradle, which consisted

of a framework or "rigging" of wood for gathering the grain together as it

was being cut, fixed to the scythe, an instrument which previous to this

time had only been used for cutting grass. The farmer, with a sweeping

stroke of his brawny arms, would cut down a "swath" of from four to six

feet in width. The binders (men and women) would follow with their rakes

and, after raking enough together for a sheaf, would twist a handful of

the stalks into a strand and bind up the bundle. An expert cradler could

cut as much as three or four acres of good standing grain in a day, about

as much as three or four men could bind. After the grain had been bound it

was gathered together and stood on end, two sheaves in a pair, in "stooks"

or "shocks" of ten or twelve sheaves, to dry.

The Reaping Machine.

The cradle was superseded by the reaping machine, which

has been the subject of many improvements up to the present time, since

its introduction in 1831, when a man walked behind and raked the grain off

the table as it was being cut. In 1845 a seat was made for this man at the

rear of the machine, and in 1863 a self- raking attachment was added,

until now we have machines which not only cut the grain but also bind it

into sheaves as well. The advent of the reaping machine is a striking

illustration of the truth of the old saying, "Necessity is the mother of

invention." The inventor, who lived in the Western States, saw the need of

a machine that would cut the grain in the big fields of the western

country just opening up to settlement more rapidly than it could be done

by the old methods. This idea of saving labor has been carried out with

all kinds of work, until now there is scarcely any department of labor in

which machinery does not do the bulk of the work.

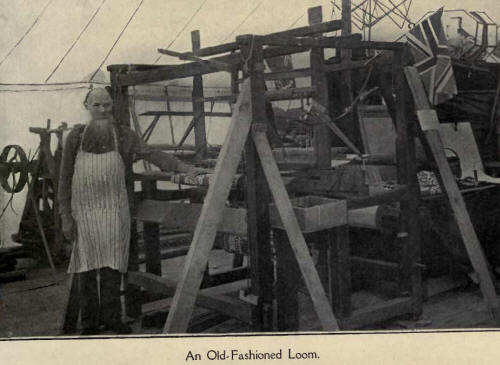

Sheep Washing and Shearing.

In the spring of the year, generally the last of May or

the first of June, the sheep were driven into an enclosure beside some

stream, and one by one taken by the farmer and his men and washed in the

stream, so as to get their wool clean and white. After a day or two of

drying the sheep were shorn of their fleeces. The wool was then picked

over by the women and girls, to get out any burs or lumps of dirt that

might have adhered to it, "picking" bees being frequently made for this

purpose. After the picking, in order to make the wool soft and pliable, it

was spread out on the floor and greased by sprinkling melted lard over it

and next whipped with a rod, after which it was bundled up in big woollen

blankets, pinned together with a thorn from a hawthorn bush and sent away

to the carding mill to be carded into rolls for spinning. Many of the

farmers, when carding mills, were not convenient, did their own carding

with the old-fashioned hand cards. If the farmer had a large number of

sheep he would often make a bee for the washing and the shearing. If the

sheep were afflicted with "tick" or vermin a solution of tobacco leaves

was made and applied to the skin of the sheep.

A flock of sheep after being sheared were and are quite a lean and

awkward-looking sight; pitiable, shivering, starving-looking creatures,

seeming different animals altogether from the well-wooled sheep that gave

good promise of fat mutton.

NOTE—Nowadays many farmers do not pay much

attention to sheep raising; they buy their clothing from the merchant and

the butcher makes his rounds through the country and supplies them with

fresh meat, but in our grandfather's time they were obliged to keep a

good-sized flock of sheep. The wool of the sheep they made into clothing,

and when fresh neat was required for family use and for the threshings,

etc., the flock was robbed of one of its most promising-looking members.

Years ago there was no market in the towns and villages for mutton and

other meats. What the farmer raised he raised for his own use principally,

as there was no foreign market as there is now.

|