|

THE FIRST STOVES—THE

OLD CORNER CUPBOARD—THE GRANDFATHER'S CLOCK—THE

OLD FLINT-LOCK MUSKET—THE DINNER HORN—THE OLD DASH CHURN.

THE first

settlers did all their cooking and

warmed their houses by means of fire-places.

Until chimneys were built, they

were obliged in some cases to let the

smoke escape by a hole in the roof. A pole was

run up

from the ground through this hole, and it is said the

smoke would circle around it, and so find its

way out.

It was necessary, of course, to keep a door or window

open in order to get a draught. It was not

until about

seventy or eighty years ago that cooking stoves first

came into use, and since then their use has

changed

things considerably, and so have the stoves, too, in

style

and shape. It was some time after their introduction,

however, before their use became universal, as

even

fifty years ago many of the farmers in the country still

did all their cooking in the old fireplaces.

Among the

first styles of cooking stoves in Upper Canada were

the

old "King" stove, with its elevated oven, the hollow

place underneath the back part of the stove being usually kept filled with

kindling and other wood to keep it dry, the "Burr" and "Davy Crockett,"

all familiar to many of the old folks, and reminders of the happy days

gone by. Big heavy box stoves, for heating purposes, were introduced at

the beginning of the century, but being expensive, the families who owned

them were few and far between, some could not afford them, and others were

slow in taking up with newfangled ideas. One of these old stoves is still

in the possession of the family of a descendant of one of the old

pioneers. It has been in constant use since before the War of 1812-14. The

writer's great-grandmother, being afraid that someone might steal or

destroy it at a time during the war when she fled with her children for

safety back into the country, had it sunk in the creek at the back of the

farm, where it lay all one winter. To this day it carries the marks of

that bath, for the rust ate into its surface, although not enough to

destroy the figures. It is a two-storey box stove, made of cast-iron

plates, so arranged that it can be taken apart in the summer time and laid

away.

In the homes of a few of the

well-to-do families was to be seen years ago the "Franklin" stove, said to

be the invention of Benjamin Franklin. It was, in the way of heating,

perhaps, the first remove from the fireplace, which it was certainly an

improvement upon, as it had a stovepipe attached, and so prevented a great

deal of the heat of the fire from passing up. the chimney., a fault with

the old fireplace. . It had, like the fireplace, however, an open front

with fire-dogs. After a while folks saw that by closing the front the fire

burned just as well, and better; this fact led to the invention of the box

stove, and later on the cooking stove.

Most of us, who have always been

accustomed to modern conveniences, can hardly imagine just what the

simple, primitive life of our forefather was like. Life in the backwoods

to-day is different to what it was in the early days of settlement.

The Old Corner Cupboard.

In a corner of the dining or

sitting-room was generally to be found the old corner cupboard, with its

glass doors; behind which were placed the porcelain, china and glassware,

the dishes covered with blue or red-colored pictures of Chinese pagodas,

of landscapes, of men, women, animals and birds. The plates were usually

set on edge around the sides of the cupboard and the nested cups and

saucers in the centre. Below the dishes were several drawers for keeping

the knives, forks and spoons in. In the bottom part of the cupboard,

behind wooden doors, were usually kept handy such articles of food as

bread, butter, sauce, a jug of milk, etc. When the children, after romping

in the orchard, around the barn and stables and over the farm, came in

tired and hungry, their kind-hearted aunt would go to the corner cupboard

and spread them a thick slice of bread and butter, with a good liberal

coating of apple sauce or "schmier kase," or perhaps give them a bowl of

bread and milk. How very good things tasted when taken out of that old

corner cupboard, with the appetite whetted by the active exercise of

youth! What epicurean dish could be manufactured to give equal enjoyment?

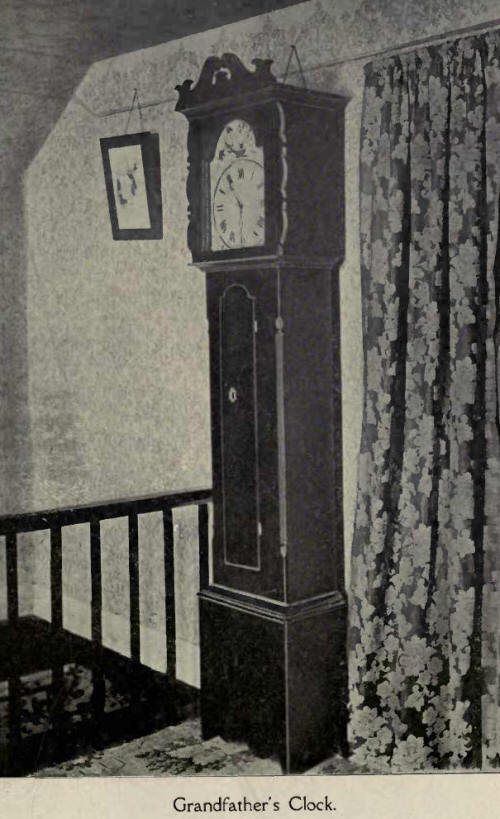

The Grandfather's Clock.

In another prominent corner of one

of the living rooms usually stood the grandfather's clock. Mostly it hung

on the wall, with the weights by which it was wound dangling in the air;

or perhaps the works were fittingly enclosed in a suitable case. With its

flowered dial, highly polished case and large pendulum, it was quite an

imposing piece of furniture, and the sound it made as it struck the hours

solemnly broke the stillness of the midnight air. With descendants of some

of the old families may still be found one of these old clocks that has

come down to them after a couple of hundred years Generations come and go,

but still the Old clock wags on, a monument of bygone days. What a pleas-

ant reminder of the old song:

My grandfather's clock was too

long for the shelf,

So it stood ninety years on the floor

It was

taller by half than the old man himself,

Though it weighed not a

pennyweight more,"

How interested we were in seeing

grandfather wind up the clock! When there was no one around, we would

sometimes stealthily open the door and peer curiously in at the works. In

many of the old clocks the wheels were made of wood, and not a few of the

more expensive kind had music boxes attached, which served to make them

still more attractive. In the early days peddlars (usually Yankees) went

around among the people introducing these clocks. After buying one, the

farmer would engage a carpenter to make a case for it. Occasionally thee

would be found a house among the poorer class of settlers in which there

was no clock, the time being told by the sunlight reaching a certain mark

on the floor. On cloudy days the time for getting dinner had to be

guessed. Sun-dials were also introduced and did the duty in some of the

houses of indicating the time.

The Old Flint-Lock Musket.

The only gun in use, by the military as well as the

people, seventy-five years ago or more was the old flintlock musket.

Breech-loading firearms were unknown. Even still, among the descendants of

some of the old settlers, are to be found some of these old guns that did

service perhaps in the War of 1812-14 and the Rebellion of 1837-38, handed

down as family heirlooms.

In the hammer of the flint-lock gun was fixed a piece

of flint, which struck a piece of steel near the flash-pan when the

trigger was pulled. This threw up the cover of the pan, flashed a spark

into it, and so ignited the powder. If the gun had not been loaded so as

to properly fill the vent hole which connected the flash- pan and the

barrel with powder, there would be a "flash in the pan" but no discharge.

The clumsy old horse pistols were made on the same principle as the guns,

there being no revolvers then.

Sometimes it was difficult to get these old

flint-lock guns to go off. If the powder happened to get the least bit

damp it would not ignite. For this reason it was necessary to protect the

gun from the wet, so as to have it in readiness. It is said the

expression, "Trust in God and keep your powder dry," was first made use of

by a certain general in the army many years ago, in the days of the

flint-lock gun, when addressing his men previous to an engagement. After

the heavy and cumbersome flint-lock gun came the gun

with the percussion pill lock. A small percussion pill was placed over the

vent hole of the gun perhaps smeared over with a little tallow to keep it

in place and free from moisture when the gun was ready for being

discharged. After the percussion pill came the percussion cap lock. Small

copper percussion caps were placed on a nipple through which the vent hole

passed.

The percussion lock was an

improvement and more convenient in every way than the flint lock, for it

did not require "priming," i.e., putting powder into the flash-pan when

loading. The percussion lock was also a "muzzle loader," i.e., the

ammunition had to be put into the end of the barrel and pounded down with

the ramrod carried in connection with the gun. It was loaded as follows:

first the powder was poured in, then a piece of wadding (generally tow,

although paper was sometimes used), was well rammed down, so that it would

be sure to fill the vent hole with the powder. On this was poured the

shot, after which another piece of wadding was shoved in to keep it down.

If not properly loaded the gun was

liable to burst and injure the marksman, perhaps blow off a hand or an

arm, or even fatally wound him. Accidents of this kind happened

occasionally. The old-fashioned flint-lock gun served both as a shot-gun

and rifle, shot being used for killing wild fowl and small animals and

bullets for larger game. Nowadays we have rifles with a special bore in

the barrel for bullets only, as well as guns for shot. Hunting was a

favorite pastime among the young men in the early days, many of them being

"good shots." When not in use the old gun stood in the corner, or hung on

the wall over the door, or against the chimney above the fireplace, where

it was kept free from rust, besides being out of reach of the children. In

the pioneer times it was used to kill bears, wolves and other wild

animals, also crows, hawks, pigeons, etc., which were so plentiful that

they were pests to the farmer, often doing considerable damage to his

crops, and not infrequently it served as a protection against marauding

bands of Indians. The hunter always carried a powder horn attached to a

string slung around his body. In addition to this he carried a bullet or

shot pouch fastened to his belt. His bullets he made by pouring melted

lead into moulds of different sizes kept for the purpose. Soldiers carried

cartridges in their pouches. When loading, they bit off the end of the

cartridge, poured a little of the powder out of the cartridge into the

flash-pan, and the remainder into the barrel after which the paper wrapper

and the bullet which was fastened to one end of the cartridge were shoved

down with the ramrod.

The Dinner Horn.

At most of the farmers' houses a

tin horn several feet long was kept for calling the men from their work in

the fields, woods and barn to their meals. If there was no horn many of

them would hang a white cloth on a pole where the men could see it. Often

the hollow tinkle of an old cow-bell served the purpose and might be heard

hoarsely reverberating over the fields and clearings. Sometimes, an old

worn-out cross-cut saw, a big steel triangle, or the used-up mould board

of a plough were hung up to a tree and hammered on, to notify the workers

that dinner was ready.

One of the writer's

great-grandfathers had a horn made of a sea-shell, a conch, which is still

in use in the family. Later on, some of the farmers had a bell placed on

the roof of the house to call the men in from their work. Its melodious

tones were never an unwelcome sound to the weary worker as he toiled in

the harvest field, in the logging field, or at the plough. It announced a

glad respite from labor, and the hungry laborer went towards the house

with an appetite for dinner few city people know anything about. To a

really hungry man everything tastes good; he does not have to pamper his

appetite with this and that dainty condiment, in order to be able to eat

enough to properly nourish his body.

It is said that even the horses

well knew the sound of the dinner bell and would sometimes stop in the

middle of the furrow and refuse to go any further until after they were

fed.

The Old Dash Churn.

The first churn in use was the old dash churn. It has

not as yet been altogether superseded, although newer styles, that are

much easier to operate, have to a very large extent taken its place. It is

doubtful, however, whether any of the new-fangled kinds make the butter

taste any sweeter and richer than that made in the old- fashioned way.

Possibly this was because of the labor required to produce it. How

patiently did the women, with their capacious calico or linen aprons tied

around them, stand beside the old-fashioned churn, and stomp away at the

cream until the oily globules were gathered into a mass of golden butter.

The first indications that the butter was coming was

the heavy sound the cream made as it thickened, and the ring of butter

which gathered around the hole in the cover through which the handle of

the dasher passed. When the cover was raised, to see how the churning was

progressing, you could see the dasher and sides of the churn covered with

cream and flecked with little pieces of butter. Sometimes hot water was

poured into the churn to raise the temperature and make the butter come

more speedily. When the cover was removed for the last time and the butter

taken out with the big wooden ladle, the children could be seen gathering

round with CUPS for a refreshing drink of buttermilk.

When the women were too busy to attend to all the

dairy matters themselves, they would place a big apron around one of the

small boys or girls, stand them on a stool and get them to do the

churning. This was labor to us children, and the time would drag wearily

until aunt came, examined the milk, and pronounced the churning finished.

Our weariness was soon dispelled, however, by a thick slice of fresh bread

and butter.

So much for such homely work and its rewards, which,

perhaps, the critical reader may not consider worthy the time bestowed

upon describing. But it must be recorded, as we have undertaken to be the

faithful chroniclers of the times and of the doings and manners of the

people of whom we write, the early pioneers of Canada.

|