|

1801-1803.

MY brother impresses

himself strongly on my reminiscences of this particular period of my

life. I was warmly attached to him. Our fishing expeditions together

on "the burn" to its very source, and along the bank of the river,

and on one occasion to Loch Ascaig; our excursions also to

Coille-an-Loist, Coill'-Chil-Mer, Cnoc-an-Eireannaich,

Suidh-an-fhir-bhig, Cnoe-an-t'sholuis-leathad, and Allochdarry for

blae-berries and cloud-berries, all now recall to my remembrance my

brother's intercourse and affection. It was about the beginning of

November, 1801, I think, that we went together to the school at

Dornoch. In the previous October some riot on the heights of

Kildonan demanded the presence of the under-Sheriff of the county,

to inquire into the particulars. The gentleman who then held office

as under-Sheriff was Mr. Hugh MacCulloch of Dornoch, better known as

an eminent Christian than as a magistrate or lawyer. His father, a

respectable burgess of Dornoch, was one of the bailies of that

burgh. His son Hugh, after receiving the rudiments of his education

at his native town, studied law in Edinburgh. When a boy at school a

remarkable event in his life took place. He had gone with one or two

other youths of his own age to bathe. It was at that part of the

Dornoch firth to the south of the town, called "the cockle ebb."

Having gone into the water he attempted to swim, and, getting beyond

his depth, sank to the bottom. His companions immediately gave the

alarm, when two or three men engaged in work hard by plunged into

the sea for his recovery. But he had been so long in the water that,

when taken out, he was to all appearance lifeless. By judicious

treatment, however, suspended animation was restored. This narrative

I received from his own lips, and he further added that, if God were

to give him his choice of deaths, he would choose drowning, for, he

said, he felt as he was in the act of sinking, and when the waters

were rushing in at his mouth and nostrils, as if he were falling

into a gentle sleep. That choice, in the inscrutable providence of

God, was given him, for about four miles above that spot, on that

identical firth, he was, with many others, drowned at the Meikle-ferry,

an occurrence hereafter to be noticed. The year of his appointment

as Sheriff-Substitute of Sutherland I do not know. His character as

a judge was ordinary. His administration of justice was free indeed

from all sorts of corruption, but it was defective in regard to

clear views of civil and criminal law. Sheriff MacCulloch, however,

shone as a man of ardent and enlightened piety. Saving impressions

by divine truth and divine agency had been made upon his mind at an

early age, and he advanced in the Christian life under the training,

and in the fellowship, of the most eminent Christians and

evangelical ministers in the four northern counties. On the evening

of his arrival at Kildonan from the heights of the parish, on the

occasion alluded to, he was drenched almost to the skin, as it had

rained heavily through the day; he especially required dry

stockings, and he preferred putting them on at the kitchen fireside.

I was directed to attend him thither; bringing with me everything

that was necessary to make him comfortable. Whilst thus engaged he

took particular notice of me, and asked me many questions about my

progress in learning, particularly in Latin. He was much pleased

with my answers, and said that, if my father would send my brother

and me to school at Dornoch, he would keep us for three months in

his own house. He repeated the same thing to my father next day at

parting, assuring him that the parochial teacher at Dornoch was

resorted to as a teacher of ability and success. The proposal was

entertained, and preparations were made for us to go thither in the

beginning of November.

The morning of the day of our departure

from under the paternal roof, to attend a public school, at last

dawned upon us. My brother and I had slept but little that night.

After breakfasting by candlelight, we found our modes of conveyance

ready for us at the entry-door. My father mounted his good black

horse Toby, a purchase he had lately made from Captain Sackville

Sutherland of Uppat, while my brother and I were lifted to the backs

of two garrons employed as work-horses on the farm. We set forward,

and both my sisters accompanied us to the ford on the burn, close by

the churchyard, whence, after a few tears shed at the prospect of

our first separation, we proceeded on our journey accompanied by a

man on foot. We crossed the Crask, and stopped for refreshment at an

inn below Kintradwell, in the parish of Loth, called Wilk-house,

which stood close by the shore. This Highland hostelry, with its

host Robert Gordon and his bustling, talkative wife, were closely

associated with my early years, comprehending those of my attendance

at school and college. The parlour, the general rendezvous for all

comers of every sort and size, had two windows, one in front and

another in the gable, and the floor of the room had, according to

the prevailing code of cleanliness, about half an inch of sand upon

it in lieu of carpeting. As we alighted before the door we were

received by Robert `'Wilk-house," or "Rob tighe na faochaig," as he

was usually called, with many bows indicative of welcome, whilst his

bustling helpmeet repeated the same protestations of welcome on our

crossing the threshold. We dined heartily on cold meat, eggs, new

cheese, and milk. "Tam," our attendant, was not forgotten; his

pedestrian exercise had given him a keen appetite, and it was

abundantly satisfied. In the evening we came to the manse of Clyne.

Mr. Walter Ross and his kind wife received us with great cordiality.

Mrs. Ross was a very genteel, lady-like person, breathing good-will

and kindness. To her friends by the ties of affection, amity, or

blood, her love and kindness gushed to overflowing. Her father was a

Captain John Sutherland, who, at the time of his daughter's

marriage, was tacksman of Clynelisb, within a quarter of a mile due

south of the manse of Clyne. After the expiry of his lease he went

to reside at Dornoch, and the farm was at the time I speak of in the

possession of Mr. Hugh Houston, sometime merchant at Brora, and the

brother of Mr. Lewis Houston of Easter-Helmisdale, whom I have

named. Mr. Ross had by his wife a son and a daughter; the daughter

died in infancy; the son, William Baillie, was of the same age with

myself, and is, at the time I write (August 1842) a physician of

repute in Tain.

After breakfast next morning we

proceeded on our journey. After having passed the Bridge of Brora

there soon burst upon our sight Dunrobin Castle, the seat of the

ancient Earls of Sutherland, the view of which from the east is

specially imposing; and here 1 may remark in passing, that the

present excellent public road which runs through the county of

Sutherland was, at the time I speak of, not in existence. In lieu

thereof was a broken, rugged pathway, running by the sea-shore from

the Ord Head to the Meikle Ferry, and at Dunrobin, instead of going

to the north of the castle as the present line does, it descended to

the sea-side, passing about two miles to the east of the castle

right below it, and so round by the south. The building filled me

with astonishment. The tower to the east, surmounted by its cupola,

the arched entrance into the court, and then the simply elegant

front looking out on the expanse of the Moray Firth, which rolls its

waves almost to the very base, were to me an ocular feast. The

garden too, on the north side of the road, over the walls of which

towered the castle in ancient and Gothic magnificence, was another

wonder. I was perfectly astonished at its extent. It stretched its

south walls at least 300 yards along the road, and at each of its

angles were rounded turrets, which gave it quite an antique

appearance, in strict keeping with the magnificent edifice with

which it was connected. The village of Golspie lies about a quarter

of a mile to the west of the castle, close by the shore, and, as we

advanced, the first object we saw was the manse, near which, on

approaching it, we noticed walking towards us a low-statured,

middle-aged man, dressed in a coarse, black suit, and with a huge

flax wig of ample form. My father and he cordially recognised one

another, and I at once discovered this venerable personage to be Mr.

William Keith, minister of Golspie. We did not stop, but proceeded

on our way to Embo, and reached the north side of the Little Ferry

house at about two o'clock. As we dismounted, and every necessary

preparation was made by the boatman to get us over, I felt a good

deal alarmed. Except when crossing the Helmisdale river in a cobble

some years before, I had never been in a boat or at sea; and I was

particularly frightened at the idea of being a fellow-passenger with

my fathers large horse and our own lesser quadrupeds, lest they,

participating in my own fears, might become unruly and swamp the

boat. Matters went on, however, better than I anticipated; the

horses, after remonstrating a little, were made to leap into the

boat, and, with my heart in my throat, I followed my father and

brother, and took my place beside them in the bow of the wherry. As

we moved off I was horror-struck, on looking over the edge of the

boat, to see the immense depth of the Perry. It was a still, clear

winter's day, and I could distinctly perceive the gravelly bottom

far below. I could see, passing rapidly in the flood, between me and

the bottom, sea-ware of every size and colour. The star-fish

intermingled with the long tails of the tangle which by the

under-swell of the sea heaved up and down, and presented the

appearance of a sub-marine grove, retaining its fresh look by the

greenish colour of the sea-water. It forcibly recalled to me Ovid's

deluge; and as we mounted our horses after crossing and rode on, I

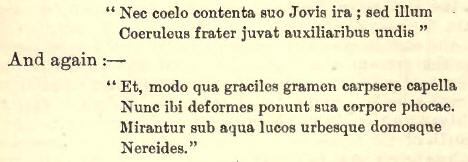

repeated to my father these lines:-

My father reminded me that it was

getting late, and that we must make the best use of our time, as

Embo was still at a considerable distance. We arrived there,

however, before it got dark, so that I had an opportunity of seeing

in fair daylight the most elegant mansion I ever witnessed, with the

exception of 1unrobin Castle. Embo House stood nearly half-way

between Dornoch and the Little-Ferry, on the old line of road. It

was the manor-house of a family of Cordons, scions of the Gordons,

Earls of Sutherland; and they had held it since the days of Adam,

Lord of Ahoye, the husband of the Countess Elizabeth. The estate was

then in the possession of a collateral branch of the family of Embo.

Robert Hume Gordon, having some years before canvassed the county,

with the view of being its representative, in opposition to the

influence of the Duchess of Sutherland, built this splendid mansion

for the purpose of entertaining the electors. Mr. Gordon lost his

election, yet by a narrow majority. He was supported by the most

respectable barons of the county, Dempster of Skibo, Gordon of

Carrol, Gordon of Navidale, Captain Clunes of Cracaig, and Captain

Baigrie of Midgarty; and most of those gentlemen, being tacksmen and

wadsetters on the Sutherland estate, gave by their opposition to the

candidate of the Sutherland family, almost unpardonable offence.

Although Mr. Hume Gordon built the house at great expense, he never

intended to reside permanently either in the mansion or in the

county; and Embo House and property were now rented by Capt. Kenneth

Mackay, who also farmed the place of Torboll from the Sutherland

family. Embo House was constructed very much after the fashion of

the houses of the new town of Edinburgh, begun on the north side of

the Nor' Loch on 26th Oct., 1767; the front was of hewn ashlar, and

consisted of three distinct houses, the largest and loftiest in the

centre, joined to the other two by small narrow passages, each

lighted by a window, and forming altogether a very imposing front.

The centre house was four storeys high—first, a ground or rather a

sunk floor, then a first, second, and, lastly, an attic storey. The

ground or sunken floor contained the kitchen and cellars, and in

front of it was a wall surmounted by an iron railing, resembling

exactly the fronts in Princes Street, Edinburgh. Outer stairs

ascended to the principal entry door, and along the whole front of

the building extended a pavement. The lesser houses, or wings, were

each of them a storey less in height than the central building; and

the attic storeys were lighted from the front wall, instead of from

the roof, by windows about precisely half the size of the rest,

which greatly added to the effect and beauty of the whole. Behind

were other two wings of the same height with those in front,

extending at right angles from the principal buildings. The interior

of the mansion corresponded with its external appearance. The

principal rooms were lofty and elegant, ornamented with rich

cornices, and each having two large windows. Captain and Mrs. Mackay

welcomed us, but not with that cordiality with which we were

received by Captain Baigrie and Mr. Joseph Gordon. Mrs. Mackay, my

step-mother's half-sister, was a neat little woman, with a pleasing

expression of countenance. She was very lady-like, but she received

us with that politeness which might be reckoned the precise boundary

between kindness and indifference. Capt. Kenneth Mackay was in the

prime of life. He was the lineal descendant of Col. Eneas Mackay,

second son of Donald, first Lord Reay, and grandson of the redoubted

William of idelness. He was therefore—failing the present family of

Reay, descendants of the laird of Skibo, and after the Holland

Mackays, descendants of General Mackay, second son of John, second

Lord Reay —the next heir to the titles and estate of Reay. His

father, John Mackay of Melness, married Esther, daughter and heiress

of Kenneth Sutherland of Meikle-Torboll, in Strathfleet, parish of

Dornoch, a small property which for generations was possessed by a

family of the name of Sutherland, cadets of the noble family of

Duffus, whose ruined castle of Skelbo we had passed on our way from

the Little Ferry to Embo. Capt. Mackay's father, I believe, sold the

property, and the family was, at his death, reduced to the greatest

extremities. His eldest son, Kenneth, born in 1756, entered the

army, where he never rose higher than the rank of lieutenant, and

was under the necessity of retiring on half-pay, at his father's

death, in order to take charge of his affairs. And never, indeed, it

is probable, were affairs so involved more judiciously managed, or

more successfully retrieved: With only his lieutenant's half-pay,

the landless heir of Meikle-Torboll took his quondam property as a

farm at a moderate rent, and at a time when agriculture was but

little understood, and its produce turned to small account, he so

successfully laboured that, in a very few years, he snatched his

father's family from starvation, and for himself acquired a

comfortable independence. At the time I first saw him he had the

farms of Torboll, Embo, and Pronsy, in the parish of Dornoch, was

factor for the estates of Reav and Skibo, and collector of the

county revenue. His children at that time amounted to six—Harriet,

Esther, Jean, Lexy, George, and John; they were (afterwards

increased to fourteen. We were both sent to sleep upstairs in one of

the attics, but I scarcely shut an eye, being so mach stunned with

the noise of the sea, which, when excited by the east wind, is at

Embo perfectly deafening. Next morning we rode into Dornoch. The

road to the town lay on its south-east side, and, as we approached

it, I was almost breathless with wonder at the height of the

steeple, and at the huge antique construction of the church. My

father brought us at once to the school. It was then taught by Mr.

John MacDonald, A.M. (King's Coll.), who, in 1806, was ordained

minister of Alvie, in Badenoch. The school was laid out in its whole

length with wide pews, or desks, running across, while the master's

desk stood nearly in the centre, so as to command a view of the

whole. There were three windows in front, and at each of them a

bench fitted up for reading and writing. The school was crowded, Mr.

MacDonald being a very popular teacher. To my father's salutation he

replied gruffly, and after being informed of the progress we had

already made, he prescribed some books; then, according to his usual

custom, on any important accession to the number of his scholars, he

gave holiday till next morning to the entire school. We then went to

the Sheriff's house. ]le was engaged in court, but we were very

kindly received by Mrs MacCulloch and her daughter, Miss Christy.

Mrs. MacCulloch showed us to our bedroom. It was at the top of the

house, an attic above an attic--a dreary, cold place, having all the

rude finishings of a coarse loft. When the Sheriff returned in the

evening he received us with the most fatherly kindness; and before

supper the family were summoned to worship, which the Sheriff

conducted with an unction and fervour which left a corresponding

impression. The

next day my brother and I attended school; and, as we continued at

Dornoch for about a year and a half—the first quarter at the

Sheriffs, and the rest of the time boarded with a man named Dempster—I

shall arrange my recollections with reference to the principal

object for which we were sent there, namely—our education. Our

teacher, Mr. MacDonald, was an excellent classical scholar, and

highly qualified to teach all the ordinary branches. But his method

was defective. He was a merciless disciplinarian, inflicting

punishment for the slightest offences, not as part of a system, but

in the gratification of temper. About a year before we came to his

school he had been tried before the Sheriff for maltreating one of

his scholars. The boy, Bethune Gray, son of Hugh Gray, a townsman,

had committed some blunder in his lesson. MacDonald harshly

corrected it, and the teacher's violence so stunned the poor fellow

that, instead of getting out of his difficulty, he became wedged

more deeply in his error. This rendered MacDonald more violent than

before, and, coming out of his desk, he seized the boy by the neck,

threw him on his face on a form, and with the knotted end of a rope

so beat him that the boy fainted, and in that state was carried home

to his father's house, where, for many weeks, he lay in bed

dangerously ill. The father petitioned the Sheriff, and a Court was

held to try the case, to which MacDonald was cited. During his

examination he behaved most rudely to the judge. The matter would

have gone hard with him, but for the interposition in his behalf of

the leading persons in the town. MacDonald threatened to resign, and

to prevent this the matter was compromised. Acknowledging that his

discipline in the particular case had been much too severe,

Macdonald came under the obligation that for the future he would

inflict chastisement, not personally, but by substitute. To this

resolution, except in one instance, of which I was myself an

eye-witness, he strictly adhered. In all cases of delinquency, when

matters between him and the delinquent came to a flogging, he acted

by deputy, and the pauper, or janitor of the school, was appointed

to inflict it. I was reading Casar and Ovid, with .fair's

Introduction, when I first entered the school, but Watt's Grammar I

had long before committed to memory. I was, however, sent back to

Cornelius Nepos and the Latin Grammar. We were also set upon a

course of English reading, but without parsing, or any knowledge of

English Grammar. A grammatical study of the English language was at

that time utterly unknown in the schools of the north, the rudiments

of Latin being substituted in its place. To the school-hours of

attendance we were summoned by the blowing of a post-horn, which the

pauper, or janitor, standing at the outer porch, blew lustily. It

was also the duty of the pauper, early in the morning, and

especially in winter while it was yet dark, to perambulate the town,

and, born in hand, to proceed to the doors or windows of every house

in which scholars resided, and blow up the sleepers. After this he

proceeded to the schoolhouse to arrange it for our reception, by

sweeping the floor and lighting the fire. For all this drudgery the

only remuneration he received was a gratis education—whence his

designation of the pauper or "poor scholar." MacDonald had

instituted a system of disgrace, for the better regulation of the

idle or disorderly among his scholars, which was, however, not

judicious. The method was this ; the first who blundered in his

lesson was ordered out of his class and "sent to Coventry," which

was the back seat, and there ordered to clap on his head an old

ragged hat, the sight and smell of which were alone no little

punishment. Under the hat, he was ordered to sit at the upper end of

the seat, and, as the leader of "the Dunciad," styled General

Morgan, If a succession of fellows, equaIIy bright, were sent to

keep him company, they held the next rank, were accommodated with

head-pieces equally ornamental, and were named in order, Capt.

Rattler, then Sergeant More, and the next was a fiddler, who,

besides his headgear, was furnished with a broken wool-card and a

stick, wherewith to exercise his gifts in the line of his vocation.

When lessons were done these unfortunate fellows were ordered out to

go through their exercise. This consisted in a dance of the

dignitaries of the squad, to the melody of him of the wool-card. On

boys of keen sensibility, and on others, the first sight of this

awkward exhibition, accompanied by shouts of laughter from their

companions, produced some salutary effect; but custom soon made it

lose its edge. The only premiums which he gave were confined to

beginners, for good writing They consisted of three quills, given

publicly on Saturday to the boy who, during the week, had kept ahead

of his class, by writing the best and most accurate copies. Such was

the system of teaching pursued at the school of Dornoch. For me it

was decidedly defective, as I only travelled over the same ground,

and that far more superficially, sin which I had advanced under my

father's tuition. For any real progress I made, in any branch of

literature, I was indebted directly to my father.

My recollections next hear upon the

Sheriff's family, with whom my brother and I lived for three months.

His house was situated to the south of the town, and at the foot of

what was called the "Fennel," a small pathway leading from the

churchyard. The house was of an antique cast. The parlour or

dining-room had three windows, and on its wall hung several prints.

In the north-west corner of the room and near the door, stood a

handsome eight-day clock—a present which the Sheriff had received

from the Sutherland Volunteers, of which he was Major. A large sofa

stood on the opposite side, near the fire-place. The study was a

small room upstairs, which was crammed with books and papers. The

Sheriff's wife was a daughter of Mr. John Sutherland, minister of

Dornoch, the immediate predecessor of Dr. Bethune. They had a

considerable family. The surviving branches of them, when we were

there, were three daughters and a son. One daughter was married to a

Mr. Cant, a flour miller of Bishop Mills, near Elgin; another

married George Munro, who first kept a shop at Wester-Helmisdale,

and afterwards leased the farm of Whitehill in the parish of Loth.

The Sheriff's son, William, was in the army, and had risen to the

rank of captain. During our residence at the Sheriff's, his son was

with his regiment in Ireland, and married; and before we left

Dornoch he and his wife came to visit his father. Captain MacCulloch

was as handsome a man as one could see; he much resembled his

father, who was also a very genteel-looking man, and must have been

very handsome in his youth. He so closely resembled Mr. Pitt, then

Prime Minister, that once, when in London, Sheriff MacCulloch was

mistaken for him on the streets, and addressed accordingly by

several persons of distinction. His other daughter, Chirsty, was

unmarried, and always resided with him. Family worship was regularly

observed morning and evening in the Sheriff's house. On Sabbath

evenings he examined all the inmates of his household on their

scriptural knowledge, concluding with an exposition of the chapter

which he had read. The people in the immediate neighbourhood usually

attended; and as some of them had no Gaelic, particularly John Hay,

a mason who lived close by the house, the concluding prayer was

given partly in one language and partly in the other, which the

Sheriff called "a speckled prayer." Every Saturday he went to

Pronsay, where he presided at a fellowship meeting; and it was these

occasions of Christian intercourse with his fellow-citizens, which

they found peculiarly edifying, that embalmed his memory in the

hearts of the survivors. He was a regular attendant at church; as,

though Dr. Bethune's doctrine seemed to him to be dry enough, he,

unlike others equally eminent for piety with himself, would not on

that account become an absentee, all the more that he held a public

office. He did not fail, however, by his restlessness of manner, to

indicate when he was not being edified.

I shall here mention a few of my

schoolfellows at Dornoch. My first acquaintances were Dr. Bethune's

sons, Matthew, Walter, and Robert. The last mentioned was not indeed

a schoolfellow, being much younger that we. Matthew was in my class,

and a most amiable fellow; he was naturally clever, but sickly from

his early youth. I only saw him once after leaving school. At

college he studied medicine, in the science of which he was not only

a profound adept, but a perfect enthusiast. After finishing his

medical course, and attending the Inverness Infirmary for a year or

two, he set up in practice there for himself. He married Miss Jean

Forbes of Ribigill, a celebrated beauty, the reigning belle of the

four northern counties. She survived him, and is married again. He

had several of a family, and one of his daughters, at least, was

married. He died in 1820, in the prime of life. His brother Walter

was not a class-fellow; he was dull and careless. I was not intimate

with him; his disposition being just as cold and repulsive as his

brother's was affectionate and winning. He did not go to college,

but at a rather early age went to Australia, where, during the rise

of the colony, he made an ample fortune, first, as a merchant, and

then as a landholder. He afterwards came to England, where he

married, and lived in receipt of an income of 91,500 per annum.

Robert, the youngest of Dr. Bethune's sons, was spoilt by his

mother. He, too, went abroad, and, marrying an American lady,

returned to a farm in the Black Isle. Soon after, he, with his wife

and family, emigrated to British America.

About the time I came to Dornoch, Hugh

Bethune came to reside at the manse, to attend MacDonald's school.

This young man was the second son of Mr. Angus Bethune, minister of

Alness in Ross-shire, elder brother of the minister at Dornoch.

Hugh's mental abilities were not of the highest order, but he had a

good, working mind, suited not so much for the higher walks of

literature, as for the business of the world. He was a forward,

smart boy, and showed a precocity for bustling his way to the

attainment of independence. Although he and I were intimate, yet my

brother and he could not agree, nor in any way pull together. Hugh

Bethune's disposition being such as I have described, it, naturally

enough, was not very agreeable to boys of his own age, who

considered themselves on a level with him. Smartness in a boy, when

among his superiors, is often little else than arrogance when in the

society of his contemporaries. Such precisely was Hugh's hearing

toward his schoolfellows. He stepped at once, and without being

asked, into the place of leader and principal adviser in all the

amusements of our play hours. He considered such a place to be his

due, and I and others were of his opinion. Not so my brother; to

arrogance and undue pretension his natural disposition was decidedly

opposed, and those bickerings at last ended in an open rupture. Now

the ordinary way of deciding such differences between schoolboys is

a boxing match ; and in just this manner did the rupture come to be

determined between Hugh Bethune and my brother. The challenge was

given and received, the place appointed, and, in the presence of

those only who had espoused Bethune's side of the quarrel, the

combatants engaged. Hugh could count as many years as my brother,

but he was far from being on an equality with him in muscular

strength, and therefore, after exchanging. a few blows, Bethune gave

in, and his friends interfered to save him from more punishment.

Notwithstanding my intimacy with Hugh Bethune, I did not exactly

relish his conduct towards my brother; and I must confess that I

indulged this feeling, and deliberately laid down a plan whereby I

thought I could avenge my brother's quarrel. Hugh, Matthew, and I

were at the time reading Caesar together; having gone over it before

with my father, I understood it better than they did, and acted

usually, when we were preparing our lessons, as their usher. Yet

such was Hugh Bethune's influence over me that, although I could

easily enough have kept the head of the class, I preferred that he

should have it, and kept him and Matthew Bethune above myself, by

prompting them when they were examined by the master. On the

occasion alluded to, I changed my plan, and when Hugh faltered in

his lesson, notwithstanding all his significant nods, I remained

silent. His cousin, as next in place in the class, was appealed to

by the master; but poor Matthew could not help him out. When it came

to my turn, I answered correctly, and then, as a glorious revenge, I

stepped above them both and took the head of the class! Hugh Bethune

afterwards went to the West Indies, in the commercial line, where he

set up as a merchant in Kingston, Jamaica. He married and had a

family, but was early cut off by fever.

Another of my school-fellows was a ragged boy, who was an excellent

arithmetician and a good reader—indeed, upon the whole, one of the

cleverest boys at school. He was very quiet, distant, and rather

unsociable. His name was George Cameron, and he is now Sheriff.

Substitute at Tain. He studied law and practised as a solicitor at

Inverness for many years; was a keen Whig in politics, and a very

clear-headed public speaker. He was twice married, first, to a

daughter of Gilbert Mackenzie of Invershin, and next to a daughter

of William Taylor.

Angus Leslie and I once, most unjustly,

got thirty lashes from the master. Beyond this fact, he made no

impression on me as a schoolfellow. Some years ago he was employed

by the late Duke of Sutherland as one of his under-factors on the

Strathnaver district of his large estate. While acting in that

capacity, he behaved with great cruelty to a mason of the name of

MacLeod, who was also a small crofter in Strathy, parish of Farr.

Leslie turned him and his family out of his house and croft in the

middle of winter, during a heavy snowstorm, and, at the same time,

forbade any of his neighbours, for miles around, to give them

shelter. This conduct led to a series of letters in the "Edinburgh

Courant," and afterwards to a controversial pamphlet, which

reflected very severely, not only on Leslie's action, but upon the

measures taken by the late Duchess of Sutherland against her

Highland tenantry in 1818. Leslie soon after resigned the

bailiffship of Strathnever, and took the farm of Torboll. He had a

brother Robert, who was a good scholar, and very amiable and

kind-hearted. He became a medical man, and went abroad.

George Taylor was only remarkable at

school for his powers of endurance under discipline. He studied law,

and for a time held the situation of county clerk. He married a

beautiful woman, Christina, daughter of Captain John Munro of

Kirkton, parish of Golspie. He is the author of two very able

articles in the "New Statistical Account of Scotland"—those on the

parishes of Loth and Kildonan.

Another of my schoolmates was Sandy

MacLean. This youth was, through his father, respectably, and

through his mother, nobly descended. His father, a lineal descendant

of MacLean of Dowart, the gallant and the brave, rose to the rank of

Captain in the British army, and fell fighting the battles of his

country. He married Miss Sutherland of Forse, a lineal descendant of

William, fifth Earl of Sutherland, and, after the Kilphedder branch,

the next in succession to the titles and estate of that earldom.

Previous to his death Captain MacLean had taken the farm of

Craigtown, in the parish of Golspie, where his widow and her

numerous family now reside. Sandy, their second son, was my

contemporary. He had a fair face and a handsome figure. Although

generous and warm-hearted, he was a wild and dissipated youth. His

passion was the army, and he left school on receiving his ensign's

commission in a Scottish regiment of the line. He was killed in the

prime of life in a duel. The occasion of it was his warm espousal of

the cause of a countryman and brother officer, who had received

gross insult from a professed duelist, and, after a challenge, had

fallen by his hand. Burning to avenge the death of his friend, poor

Sandy challenged the murderer, and was himself mortally wounded.

Some of my schoolfellows, with whom I

was most intimate when at Dornoch, were three young men of the name

of Hay. They were natives of the West Indies; the offspring of a

negro woman, as their hair, and the tawny colour of their skin, very

plainly intimated. Their father was a Scotsman, but I never learned

particularly anything more of him. Fergus, the eldest, was about

twenty years of age when I was at school, and attended merely to

learn the higher branches of mathematics, in order to fit him for

commercial duties. Notwithstanding the disadvantages of his negro

parentage, Fergus was very handsome. He had all the manners of a

gentleman, and had first-rate abilities; but he had the indomitable

pride of an Indian potentate, and over his younger brothers, John

and Alexander, he exercised an absolute sway. Even MacDonald himself

quailed before the lordly bearing of Fergus Hay. I was a great

favourite of his, but our friendship had rather a hostile beginning.

For the thirty lashes which I so unjustly received, I was indebted

chiefly to Fergus. He it was whom the master in his absence had

appointed censor; and—merely to save the skins of Walter Bethune,

Bob Barclay, and others, who made the noise, but for whom both he

and the master had at the time a favour—who caused Angus Leslie and

me to be made the victims. Fergus Hay was conscious of the

impropriety of his conduct towards me, although his pride would not

allow him to say so; for, from that day till he left school, which

he did about half a year after, be behaved to inc with very great

kindness. His brother John and my brother were sworn friends; John

Hay was considerably older than he, and of more than ordinary

strength. Alexander, the youngest, was a peaceable lad. Whilst at

Dornoch we often made excursions, on Saturdays and other holidays,

to many places in the neighbourhood together; particularly to the

Ciderhall wood, and to the elegant place of Skibo, where we used to

roam through the woods and not return till late. At the harvest

vacation my brother and I usually went home, and on one of these

occasions John and Sandy accompanied us, and remained a week at

Kildonan. When

at school at Dornoch we had our holiday games. Of these, the first

was "club and shinty" (cluich' air phloc). The method we observed

was this—two points were marked out, the one the starting-point, and

the other the goal, or "haile." Then two leaders were chosen by a

sort of ballot, which consisted in casting a club up into the air,

between the two ranks into which the players were divided. The

leaders thus chosen stood out from the rest, and, from the number

present, alternately called a boy to his standard. The shinty or

shinny, a ball of wood, was then inserted into the ground, and the

leaders with their clubs struck at it till they got it out again.

The heat of the game, or battle as I might call it, then began. The

one party laboured hard, and most keenly, to drive the ball to the

opposite point or "haile" the other to drive it across the boundary

to the starting-point; and which party soever did either, carried

the day. In my younger years the game was universal in the north.

Men of all ages among the working classes joined in it, especially

on old New Year's day. I distinctly recollect of seeing, on such

joyous occasions at Dornoch, the whole male population, from the

grey-headed grandfather to the lightest-heeled stripling, turn out

to the links, each with his club; and, from 11 o'clock in the

forenoon till it became dark, they would keep at it, with all the

keenness, accompanied by shouts, with which ttieir forefathers had

wielded the claymore. It was withal a most dangerous game, both to

young and old. When the two parties met midway between the two

points, with their blood up, their tempers heated, and clubs in

their hands, the game then assumed all the features of a personal

quarrel; and wounds were inflicted, either with the club or the

ball, which, in not a few instances, actually proved fatal. The

grave of a man, Andrew Colin, father of one of my school-mates, was

pointed out to me, as that of one who was mortally wounded at a club

and shinty game. The ball struck him on the head, causing concussion

of the brain, of which he died.

Among our amusements was our

pancake-cooking on Pasch Sunday (or Di-domhnaich chaisg), and in

February, the "cock-fight." This last took precedence over all our

other amusements. About the beginning of this century there was

perhaps not a single parochial school in Scotland in which at its

season the "cock-fight" was not strictly observed. Our teacher

entered, with all the keenness of a Highlander and with all the

method of a pedagogue, into this barbarous pastime. The method

observed at Dornoch was as follows:—The set time being well known

(am cluiche can coileach), there was a universal scrambling for

cocks all over the parish; and we applied at every door, and pleaded

hard for them. In those primitive times, people never thought of

demanding any pecuniary recompense for the birds for which we dunned

them. When the important day arrived, the court-room itself, in

which was administered municipal rule, and where good Sheriff

MacCulloch ordinarily held his legal tribunal, was surrendered to

the occasion. With universal approval, the chamber of justice was

converted into a battle-field, where the feathered brood might, by

their bills and claws, decide who among the juvenile throng should

be king and queen. The council-board was made a stage, and the

Sheriff's bench was occupied by the schoolmaster and a select party

of his friends, who sat there to give judgment. Highest honours were

awarded to the youth whose bird had gained the greatest victories;

he was declared king, while he who came next to him, by the prowess

of his feathered representative, was associated in the dignity under

the title of queen. Any bird that would not fight when placed on the

stage was called a "fugie," and became the property of the master. A

day was appointed for the coronation, and the ladies in the town

applied their elegant imaginations to devise, and their fair fingers

to construct, crowns for the royal pair. When the coronation day

arrived, its ceremonies commenced by our assembling in the

schoolhouse. The master sat at his desk, with the two crowns placed

before him; the seats beside him being occupied by the "beauty and

fashion 'S of the town. The king and queen of cocks were then called

out of their seats, along with those whom their majesties had

nominated as their life-guards. Mr. MacDonald now rose, took a crown

in his right hand, and after addressing the king in a short Latin

speech, placed it upon his head. Turning to the queen, and

addressing her in the same learned language, he crowned her

likewise. Then the life-guards received suitable exhortations in

Latin, in regard to the onerous duties that devolved upon them in

the high place which they occupied, the address concluding with the

words, "itaque diligentissime attendite." A procession then began at

the door of the schoolhouse, where we were all ranged by the master

in our several ranks, their majesties first, their life-guards next,

and then the "Trojan throng," two and two, and arm in arm. The town

drummer and fifer marched before us and gave note of our advance, in

strains which were intended to be both military and melodious. After

the procession was ended, the proceedings were closed by a ball and

supper in the evening. This was duly attended by the master and all

the "Montagues and Capulets" of Dornoch. [During the eighteenth

century, cock-fighting was practised as an ordinary-pastime in the

parish schools of Scotland. It was observed on Shrove Tuesday, or

s'astern's E'en, as it was called. The custom was condemned in 1748

by John Grub, schoolmaster of Weymss, in Fife, in a Disputation

composed by him to be read by his pupils to their parents, but was

continued in practice for eighty years later. The celebration which

followed on the above occasion was usually observed on Candlemas,

old style, or the 13th of February. (See Dr. Rogers' "Social Life in

Scotland.") —ED.]

The inhabitants of Dornoch next claim my

recollection. Dornoch is the only burgh in the county, and although

it is not less important than Tain as a seaport town, its trade has,

for nearly half a century, been considerably on the decrease. My

personal acquaintances among the inhabitants were to be found in all

ranks and grades. I have described the Sheriff and his household.

Mr. MacCulloch's eminent piety and Christian fellowship have

enshrined his memory in the hearts of all who knew him. It was

during our stay in his house that my uncle, Dr. Alex. Fraser of

Kirkhill, died. I had just come in from school, and found the

excellent Sheriff in tears. I did not presume to ask him the reason,

but he understood my enquiring look. " Ah," said he, "I mourn your

loss as well as my own and that of the Church; a prince has fallen

in Israel—your uncle, Dr. Fraser, is no more." My most distinct

recollection of the Sheriff afterwards is when I saw him in the

Major's uniform of the Sutherland Volunteers; he made a speech in

Gaelic to the men, who were drawn up before him.

My next acquaintance of importance was

with the family at the manse. Dr. Bethune's manners were most

attractive to all classes, particularly to the young. His personal

appearance and expression of countenance warmly seconded the

amiability of his manner. Ile had piercing black eyes, and his nose,

being what is usually called "cocked," gave a strong expression of

good humour to his face. His hair was dark, and, although he was

past fifty at the time, it was but slightly touched with grey. Ibis

conversation was humorous, interspersed with shrewd remarks, or

lively anecdotes, at which he himself laughed with so much glee that

others felt compelled to join him. Mrs. Bethune was a lively,

pleasant woman. Quite the lady in her manners, her character was

formed after the fashion of the world. To her husband she was an

helpmeet in everything but in that which belonged to the sacredness

of his office. From her father, Joseph Munro, minister of Edderton,

she had imbibed such a measure of the chilling influence of

Moderatism, as to repress any kindly ministerial intercourse between

her husband and the pious and lower classes of his parishioners. Dr.

Bethune would have been far more intimate with his people, and more

useful among them, if this sort of home influence had not been

brought to hear upon him. Their eldest son, John, died young; their

second son, Joseph, was in the army. Their eldest daughter, Christy,

married Capt. Robert Sutherland, H.E.I.C.S. His other daughters were

Barbara and Janet; the former married Col. Ross, once of Gladfield,

afterwards of Strathgarvie; Janet remained unmarried, and latterly

resided at Inverness.

Among my other acquaintances were Mr.

Taylor, sheriff-clerk; Mr. Leslie, procurator-fiscal; Hugh Ross, or

"Hugh the laird;" and James Hoag, the architect. Of Mr. William

Taylor I had many pleasant recollections. He was a native of Tain,

and the eldest of four brothers, all of whom I subsequently knew. He

married a daughter of Captain John Sutherland, who by her mother

was, through the Kirtomy family, a cousin of my father. Mrs. Taylor

was a warm-hearted, motherly person, and lived to an advanced age.

They had a numerous family. George, the eldest, was my contemporary

at school. Robert, the second son, succeeded his father in all the

public offices which he held in the county, acted as procurator

before the Sheriff Courts, married Mary, youngest daughter of the

late Colonel Munro of Poyntzfield, and was appointed

Sheriff-Substitute, first, in the Island of Laws, and afterwards at

Tain. Hugh Leslie, the fiscal, was both an innkeeper and the

procurator in the Sheriff Court. All sorts of people frequented his

inn; and often during the markets periodically held at Dornoch,

fierce, disorderly fellows quarrelled and fought with each other

there, like so many mastiffs. On such occasions Mrs. Leslie, who was

an amazon in size and strength, came in as "third's man," followed

by her ostler, "Ton'l," as we usually called him, a strong fellow

from Lochbroom. When her guests were fixed in each other's throats,

Mrs. Leslie made short work with them, by planting a grip with each

hand on the back of their necks, tearing them apart, and finally by

holding them until her ostler, by repeated and strong applications

of his fists, had sufficiently impressed them with a sense of their

conduct. Although Mrs. Leslie, however, thus so much excelled all

males and females of her day in strength and resolution, and did not

hesitate to exert both on pressing occasions, yet she possessed an

amiable temper. Her expansive countenance had a mild expression; her

height was at least six feet, and her person extremely robust. In

her latter days she became a true Christian, and her death-bed was

triumphant. Hugh Leslie's bodily presence was always made known by

his cough. His legal attainments and appearance as procurator I

still remember. During play-time I would frequently spend half an

hour in the court-house, and I have often come upon Hugh Leslie in

the midst of one of his forensic orations. He made use of no

ingenuity of argument, or of special pleading; but he took up all

the strong points of the case, and battered away at them, until, in

ten cases for one, he was ultimately successful. His second son,

Angus, was my fellow-scholar. "Hugh the laird" was another of the

Dornoch lawyers. He was a highly-talented and accomplished, but most

eccentric man. He had studied law with Sheriff MacCulloch at

Edinburgh, and had evidently seen better days. In court, he was

usually Leslie's opponent; and no two men could possibly present,

even to those least capable of observation, a more complete

contrast. " The laird " was cool, clear and eloquent. Abstract views

of the common law, brought to hear upon the case of his client with

far more ingenuity than solidity of reasoning, where the forensic

weapons which he brandished in Leslie's face, much to his annoyance,

and, not unfrequently, to his discomfiture. Poor Leslie's arguments,

which he delivered with such heat and rapidity, that he could

neither illustrate them with sufficient clearness of expression, nor

very distinctly remember them when he had finished, his cool and

more able opponent took up one by one, and demolished, with pointed

wit and sarcasm. Ross held up all his words and arguments, from

first to last, in a light so distorted and so perfectly ludicrous,

that his fiery little antagonist could not recognise there again,

but, starting to his feet, while " Hugh the laird " was going on, he

would hold up both his hands, and, trembling with rage, cry out, "O,

such lies! such lies! did ever you hear the like?" 'These explosions

of temper Ross met by a graceful bow to the bench, and a request to

the Sheriff to maintain the decency of the court. James Boag, the

architect, a very old and a very odd man, then lived at Dornoch. He

was a carpenter by trade, and was by extraction from the south

country. In his younger years he had lived at a place called Golspie

Tower, rented as a farm from the Sutherland family, where he got

into an extensive business, having become contractor, almost on his

own terms, for most of the public buildings, as well as for many

gentlemen's houses, in the counties of Ross and Sutherland. All the

churches and manses in Sutherland and Easter-Ross built between 1760

and 1804, were according to the plans, and were the workmanship of

James Boag. These plans were in almost all cases identical; that is,

for churches, long, narrow buildings, much resembling granaries, in

which convenience and acoustics were equally ignored. His manses we

have already described in that of Kildonan. lie built the church of

Resolis, in Mr. MacPhail's time, in 1767; and the church of Kildonan,

during my father's incumbency, in 1788. When a school-boy at Dornoch

I never could meet Boag, or even see him at a distance, without a

feeling of terror. He lived mostly at Dornoch, but spent a

considerable part of the year at Skelbo, which he held in lease. He

terrified all the school-boys, as well as every inmate of his own

house, by the violence of his temper and his readiness to take

offence. His son-in-law, Mr. William Rose, was decidedly pious, as

was also firs. Rose. After Dr. Bethune's death, she was one of

several eminent Christians who petitioned the Marchioness of

Stafford, as patron, in my favour. They were not successful, and I

was utterly unworthy of such an honour; but it is a consolation to

think that, although I did not thereby become minister of Dornoch, I

was, notwithstanding, the choice of those who were owned and

honoured of God. Mr. Rose died at an advanced age. He was one of the

elders of the parish, and his Christian character may be summed in

this, that he was distinguished for simplicity and fervour, "a good

man, full of faith and of the Holy Ghost."

Two antiquated ladies lived in the town,

Miss Betty Gordon and her elder sister Miss Anne. I mention the

younger first, because the elder sister was always ailing, and

seldom visible to the outdoor public. Miss Betty herself was too

feeble to walk out, but she usually sat in the window in the

afternoon, dressed after the fashion of 1699, in an ancient gown,

with a shawl pinned over her shoulders, and a high cap as head gear.

Like all females, perhaps, in the single state and of very advanced

age, she was very fond of society, and of that light and easy

conversation otherwise termed gossip. When therefore she took her

station at her upper window, a female audience usually congregated

below it. These attendants gave her the news of the day; and she

made her remarks upon it, as full of charity and goodwill towards

all as such remarks usually are. These two old ladies were as

ancient in their descent as they were aged in years. Daughters of

the laird of Embo, they could trace direct descent from the noble

family of Huntly, through Adam, Lord of Aboyne. Their brother was

the last laird in the direct line, and was the immediate predecessor

of Robert Hume Gordon of Embo.

The public fairs of this little county

town made a considerable stir. From the Ord Bead to the Meikle

Ferry, almost every man, woman, and child attended the Dornoch

market. The market stance was the churchyard. Dornoch was what might

strictly be called an Episcopalian town; and the consecrated

environs of the Cathedral was just the place which the men of those

days would choose, either for burying their dead or holding their

markets. The churchyard therefore became the only public square

within the town. The evening previous to the market was a busy one.

A long train of heavily-loaded carts might be seen wending their

weary way into the town, more particularly from Tain, by the Meikle

Ferry. The merchants' booths or tents were then set up, made of

canvas stretched upon poles inserted several feet into the ground,

even into graves and deep enough to reach the coffins. The fair

commenced about twelve o'clock noon next day, and lasted for two

days and a half. During its continuance, every sort of saleable

article was bought and sold, whether of home or foreign manufacture.

The first market at Dornoch that we attended took place six weeks

after our arrival at the town. The bustle and variety of the scene

very much impressed me. The master gave us holiday; and as my

brother and I traversed the market-place, pence in hand, to make our

purchases, all sorts of persons, articles, amusements, employments,

sights and sounds, smote at once upon our eyes, our ears and our

attention. Here we were pulled by the coat, and on turning round

recognised, to our great joy, the cordial face of a Kildonaner;

there we noticed a bevy of young lasses, in best bib and tucker,

accompanied by their bachelors, who treated them with ginger-bread,

ribbons, and whisky. Next came a recruiting party, marching, with

"gallant step and slow," through the crowd, headed by the sergeant,

sword in hand, and followed by tue corporal and two or three

privates, each with his weapon glancing in the sunlight. From one

part of the crowd might be hoard the loud laugh that bespoke the gay

and jovial meeting of former acquaintanceship, now again revived;

from another the incessant shrill of little toy trumpets, which fond

mothers had furnished to their younger children, and with which the

little urchins kept up an unceasing clangour. At the fair of that

day I, first of all, noticed the master perambulating the crowd, and

looking at the merchants' booths with a countenance scarcely less

rigid and commanding than that with which he was wont invariably to

produce silence in the school.

Another incident of my school-boy days

at Dornoch was a bloody fray which took place immediately after the

burial of Miss Gray from Croich. The deceased was of the Sutherland

Grays, who about the beginning of the last century, possessed

property in the parishes of Creich, Lairg, Rogart, and Dornoch. She

came down from London to the north of Scotland for change of air,

being in a rapid decline, but did not survive her arrival at Creich

longer than a month. Her remains were buried beside those of her

ancestors in the Cathedral of Dornoch. The body was accompanied by

an immense crowd, both of the gentry and peasantry. In the evening,

after the burial, there was a dreadful . fight. The parishioners of

Dornoch and those of Creich quarrelled with each other, and fists,

cudgels, stones, and other missiles were put in requisition. The

leader of the Creich combatants was William Munro of Achany. I sat

on a gravestone, at the gable of the ruined aisle of the cathedral,

looking at the conflict. Broken heads, blood trickling over enraged

faces, yells of rage, oaths and curses, are my reminiscences of the

event. Dr. Bethune narrowly escaped broken bones. As he was walking

up to obtain ocular demonstration of the encounter, he was rudely

attacked by two outrageous men from Creich. They threatened to knock

him down; but some of his parishioners, coming just in time, readily

interfered, and his assailants measured their length on the highway.

Our visits to the manse of Creich were

not to be forgotten. Worthy Mr. Rainy's face and figure, his grey

coat, his fatherly reception of us, his motherly and amiable

wife--over "on hospitable thoughts intent " —his daughter Miss Bell,

afterwards Mrs. Angus Kennedy of Dornoch, and his sons George and

Harry, rise up and pass distinctly before inc. Mr. Rainy made a most

favourable impression upon me when I first saw him. He was a short,

stout man, with full eyes and a most intelligent, expressive face,

of which every feature was good, and every one of them said

something peculiar to itself. His little parlour, for which he had a

special predilection, had a small window in front, an old-fashioned

iron grate in the chimney, and a whole tier of presses and beds,

with wooden shutters painted blue, running along the whole extent of

the north wall. This was his constant resting-place. Here he slept,

breakfasted, dined and supped. The parlour was so much to his mind

that it was with difficulty he could be got out of it. He lived in

rather a genteel neighbourhood, and when, in the exercise of

hospitality, and of a kindly interchange of civilities between

himself and his people, he made provision for their entertainment, a

well-furnished drawing-room came into requisition. But this room

was, during his stay in it, little better than a prison. He sat by

the fire, but there was no rest for him, not for a moment. He never

ceased to paw the carpet with his right foot during the whole time

he remained there; and nothing but a retreat to the parlour, and the

settling of himself in his arm-chair, could put an end to his

impatience. Mrs. Rainy was a very pleasant-looking woman, somewhat

taller than her husband. The great attraction of her countenance was

its unequivocal expression of kindness. If any child had missed its

mother, and had met Mrs. Rainy, the conclusion in the child's mind

most have been irresistible—that Mrs. Rainy could be none else than

the "mother" so long sought for. She was never weary in well-doing,

and had an ear to listen to, and a heart to feel for, every

individual case, whether of joy or sorrow. It was during my visits

whilst at Dornoch school to the manse of Creich that I first saw and

became acquainted with James Campbell, a native of that parish. He

afterwards was my class-fellow during my four years' attendance at

college, my fellow-student at the hall, my fellow-probationer before

the Presbytery of Dornoch, and ultimately, in 1824, my father's

successor at Kildonan. James attended duly at the manse of Creich to

be instructed by Harry Rainy in the Latin Tongue. He was, at the

time, a full-grown man, afflicted with a more than ordinary measure

of poverty. To teach him anything was no easy matter, the

difficulty, on the part of the teacher, consisting entirely in his

being utterly puzzled what method to fall upon so as to convey any

kind of knowledge through the "seven-fold plies" of his pupil's

natural stupidity. George and Harry Rainy, until they both went to

college were their father's pupils. He was an accomplished classical

scholar and, bating a little heat of temper, a first-rate teacher.

Respecting the antiquities of Dornoch, I content myself with a very

few remarks. The etymology of the name is Celtic, and means "the

horse's hoof, or fist." The name was derived from the prowess of one

of the family of Sutherland, at a battle fought between the Danes

and the men of Sutherland, close by the shore, about a quarter of a

mile to the east of the town. In the action the Danes were defeated,

owing chiefly to the dreadful carnage of their men by this gigantic

chief, who, Samson-like, had no other weapon than the leg of a

horse, with the hoof of which he slew "heaps upon heaps." The hero

of the day was himself unfortunately killed towards the close of the

action. In memory of his heroism, an obelisk was erected on the

spot, of open work, which still remains. When I was at Dornoch it

lay on the ground in fragments; but it has been re-erected by the

late Duchess of SutherIand, to perpetuate the memory of her

ancestor. Dornoch, in point of extent, commerce and population, is

the "Old Sarum" of Scotland. In ancient times, however, it was a

place of considerable importance. It was the seat of a bishopric, in

which stood the church of St. Barr, and the cathedral built by

Gilbert Murray in 1222. [Gilbert Murray, bishop of Sutherland and

Caithness, was commonly called by the natives, "Gilbard Naomb," or

Saint Gilbert, because he had been canonised by the Roman Catholic

Church. He was bishop for 20 years, during which period he laboured

with much energy and zeal to instruct and civilize the people of his

rude diocese. The 1st of April, 1240, is given as the date of his

death. The fragment of an ancient stone effigy, within the Cathedral

of Dornoch, is believed to mark his grave.—Ed.] This cathedral,

except the steeple, was burnt, in 1570, by the Master of Caithness

and Mackay of Strathnaver, after a contest with the Murrays, vassals

of the Earl of Sutherland; but it was reconstructed by Sir Robert

Gordon, tutor of Sutherland, when it received its present form. It

was originally built in the shape of a cross; the nave extended to

the west, the transepts from north to South, and the choir to the

east; and each of these four aisles met together under a huge square

tower, surmounted by a wooden steeple. The last of its bishops was

Andrew Wood, translated from the Isles in 1680, and ousted by the

Revolution in 1688. After it became a Presbyterian place of worship,

the west aisle was allowed to fall into decay, and was converted

into a burial. ground, the other three being sufficient for a large

congregation. In 1816 the roof was ceiled, and a gallery erected.

But the last and most splendid renovation of this ancient fabric was

that undertaken by the Duchess of Sutherland in 1835-7, by which it

has become one of the most elegant structures, but one of the most

unsuitable places of worship, in the Empire. The ruins of the west

aisle were cleared away, and the nave re-erected, in chaste,

modern-Gothic style, on the site, with a beautiful window and

doorway in the gable; the other aisles were also renewed to

correspond with it. Many additional windows were pierced, and filled

with frosted glass; the bartizan of the tower was coped with•stone;

the steeple was built anew; and, instead of the old, crazy,

one-faced, single-handed clock, a new one, of the best workmanship,

was erected in the steeple, with four dial plates, each furnished

with an lour-and-minute-hand. As to the interior, the four aisles

present one unbroken space within. The extreme height of the ceiling

from the floor is upwards of 50 feet, and the distance from the

pulpit, which rests against the north-east pillar of the tower, to

the western door, is more than 70 feet. On the ceiling, at the

spring of the roof, is a profusion of ornaments, interspersed with

images both of men and animals; amongst the latter the cat of the

Sutherland crest is conspicuous. The object of the Duchess, in this

restoration, was to provide a mausoleum for the remains of her late

husband, and for herself; and for this purpose she spared neither

her own purse, nor the feelings of her people; for, in the course of

the operations, she caused the very dead to be removed from their

resting-place. More than fifty bodies were dug out of their graves

in order to clear out a site for her own burial-vault, under the

west aisle; the remains of the Duke having been deposited in a vault

under the east aisle. The melancholy remains of mortality,

consisting of half-putrefied bodies, bones, skulls, hair, broken

coffins, and dingy, tattered winding-sheets, were flung into carts,

without ceremony, and carried to a new burying-ground, where,

without any mark of respect, they were thrown into large trenches

opened up for their reception. The scene was revolting to humanity;

but it was a fitting sequel to her treatment of her attached

tenantry, whom, by hundreds, she had removed from their homes and

their country.

The other remarkable relic of antiquity in Dornoch is the Castle, or

Bishop's Palace. When I was at school these Castle ruins were the

favourite resort of the more venturous among us, who went there in

order to harry the nests of the jackdaws that built among the

crumbling walls. The space which it enclosed still goes by the name

of the Castle Close. The original structure seems to have consisted

of two towers connected by a screen. Only one of these towers, with

a fragment of the intermediate building, survives the ravages of

time: the only part of the screen remaining being a huge

chimney-stalk, containing the vent of the bishop's kitchen, which

was below in one of the sunk floors. In the tower, access is gained

to all its apartments by a spiral stone staircase, contained in a

small rounded tower, projecting laterally from the side of the large

tower, and running up its whole height. Below are subterraneous

vaults, about ten feet high and arched at the top. A tradition among

the people about the castle, for its site is now covered with hovels

of the poorest of the inhabitants, was that it stood upon a "brander

of oak." This meant, I suppose, that, as the soil was light and

sandy, the castle was founded upon oaken piles driven deep into the

ground. This castle was the bishop's town residence, or manor-house.

He had besides two country residences, each of which were castles:

Skibo, a few miles to the west of Dornoch, and Scrabster, in the

immediate vicinity of Thurso, in Caithness. The Castle of Skibo was

demolished in the last century, and that of Dornoch was, along with

the Cathedral, burnt in 1567 by the Master of Caithness, in his

conflict with the Murrays. It has since been partly rebuilt and

fitted up as a court-house and prison. There were also two other

ecclesiastical buildings, over the ruins of which I loved to

clamber, and whose form and structure pointed to a remote origin.

One stood at the cast and the other at the west end of the town.

That at the east had small vaulted apartments and a stone

winding-stair. The people called it the "Chanter's house," and the

farm in the immediate neighbourhood was called "Ach-a-chantoir." The

ruin to the west was called " the Dean's house," and was a plain

building with a jamb, or back wing, attached to it. It was tenanted

for long after the Revolution, and, about twenty years before I was

born, was occupied as an inn by a man named Morrison. The site has

since been feued and built over, though when we were at school it

was a ruin. For Mr. Angus Fraser, merchant, some years afterwards

took it as a feu, pulled down the ruins, and erected his house on

the site. But

the trade of Dornoch is at present a nonentity. Its markets, so

flourishing in forjner times, have almost ceased to exist. Its

population has decreased to about one-half the number it used to be.

Its merchants, or shopkeepers, are not more than two or three; if a

retailer sets up in any part of the parish or county he succeeds,

but if he removes to Dornoch he almost immediately becomes a

bankrupt. There seems, in short, to hang over the place a sort of

fatality, a blighting influence which, like the Pontine marshes at

Rome to cattle, is fatal to trade, house-building, mercantile

enterprise, or even to the increase of the genus home in this

ill-starred and expiring Highland burgh. From the first it had to

contend against its surroundings. The town is situated on a neck of

land running out into the Moray firth at its junction with the firth

of Tain. Around the town the soil is arid, sandy and unproductive,

and so notorious for sterility was its location of old that,

according to my earliest recollections, it went under the

descriptive appellative of "Dornoch na gortai," or Dornoch of the

famine. Its immediate locality, too, is bleak and bare as a Siberian

desert. Though close by the sea, it has not only no harbour, but no

natural capabilities for any possibility of having one. An almost

stagnant burn flows slowly through it, but it vanishes in mounds of

sand before reaching the sea. The estuary, which stretches to the

west, is crossed at its embouchure into the Moray firth by a bar,

formed by the lodgment of many centuries of all the sediment washed

into it by the rivers Shin, Oykcll, Carron, and Evelix. This bar,

well known to mariners by the name of "The Gizzen Briggs" (called in

Gaelic, "Drochaid an Aoig," or the Kelpie's bridge), is an

insuperable bar to the development of Dornoch as a seaport town. But

it might still have retained some of its former prosperity had it

been held in kindlier hands. The greater part of it is the property

of the family of Sutherland. They have purchased, of late, all the

houses for sale, only to level them with the ground, and, by setting

up villages and markets in other places, have destroyed its trade

and reduced its population. |