|

1753-1782.

MY father, Alexander

Sage, minister of Kildonan, Sutherlandshire, my grandfather's sixth

son, was born at the manse of Lochcarron on the 2nd of July, 1753.

After acquiring the first rudiments of his education under the

paternal roof, he was sent to the school of Cromarty. The teacher,

Mr. John Russel, was a man of great worth, an expert scholar, and a

licentiate of the Church. The gentry, the clergy, and the upper

class of tenants, in the shires of Ross, Cromarty, and Inverness,

sent their sons to his school. His method of teaching had not

perhaps the polished surface of those systems which are most

approved of now, but it was minute, careful, and substantial. In the

elementary rules his pupils received a training they could never

afterwards forget. My father could, at the age of seventy, repeat

the construction rules of Ruddiman's "Rudiments" and of Watt's

"Grammar" as accurately and promptly as he was accustomed to do when

the fear of Mr. John Russel was before his eyes. When the pupils

began to read Latin, they were taught to speak the language at the

same time. Among the more advanced classes not a word in the school

did any of them dare address to the teacher, or to each other, but

in Latin, and thus they were made familiar with the language. Mr.

Russel was a most uncompromising disciplinarian. The dread of his

punishment was felt, and its salutary exercise extended, not only

within the four corners of the schoolroom, but over the length and

breadth of the parish. The trifler within the school on week-days,

the sauntering lounger on the streets or oil the links of Cromarty

on the Sabbath-days, had that instinctive terror of Mr. Russel that

the beasts are said to have of the lion. The truant, quailing under

his glance, betook himself to his lesson; the saunterer on the

links, at the first blink of him on the brae-head, returned to his

home. In addition to this peremptoriness, Mr. Russel exercised a

spirit of vital piety. Profoundly versant in Scripture truth and in

experimental religion, he was the companion of all who feared God.

His love of discipline arose from a love of God, of moral duty, and

of the sacred rights of an enlightened conscience.

A characteristic

anecdote is related of him. Mr. John Cameron, a student of divinity

and parochial schoolmaster of Tain, was on his trials before the

Presbytery with a view to license. This young man possessed a fund

of natural humour, and would not hesitate, for the sake of a jest,

to sacrifice that which was important and sacred. He was afterwards

minister of Falkirk in Caithness. Mr. Cameron and Mr. Russel were

fellow-travellers on their way to the Presbytery seat where Mr.

Cameron had some of his trial discourses to deliver before the

court. They were at such a distance from their journey's end that

they had to take up their quarters at an inn by the way. Mr. Cameron

said that he had composed and committed to memory three Calvinistic

prayers to offer before the Presbytery. Having fixed them in his

memory, he kept them there in retenite, he said, to give them fresh

to the Presbytery. Mr. Russel, however, contrived, much to poor

Cameron's annoyance, to extract every one of them from him before

they parted. When they came to the inn, and before they had their

supper, Mr. Russel proposed family worship. To this Mr. Cameron did

not venture to object; besides, as Mr. Russel was a preacher of some

standing, he had no apprehension that there would be any demand for

his personal services. He was mistaken. Mr. Russel asked him to

pray, "and the end of it was," as Cameron himself told it, "that off

went one of my best prayers." After supper they were shown to their

beds, and were to be bed-fellows. Mr. Cameron was about to hasten to

a corner of the room to his private devotions, but Mr Russel

prevented him. "My friend, it is more becoming that we should pray

together first, and then pray separately before we go to bed; and,

as you are to be engaged to-morrow in prayer and preaching, you

cannot any better prepare yourself than by being frequently engaged

in social prayer." Mr. Cameron felt that an inroad had already been

made on his stock of prayers, and to the new proposal he stoutly

objected. But it would not do. Mr. Russel was peremptory—he must

again pray; "so," as he related, "down I bent to my knees, and away

went two-thirds of my stock." In the morning, when they were both

dressed, Mr. Russel said, "We are entering upon our journey, and we

ought to begin it with prayer together; let us kneel, and you'll

proceed: it will suitably prepare you, and put your mind in a proper

frame for the duties before you. Cameron resisted the proposal, but

to no purpose. "I repeated my last prayer," said Cameron, "and where

or how to get new ones in place of them I didn't know, unless I

could splice them together."

Mr. Russel was a

preacher of great power and unction. In 1774 he was settled minister

of the high Church, Kilmarnock, and from thence he was, in the year

1800, translated to Stirling, where he continued until his death in

the year 1817.

Mr. John Russel,

minister of the second charge of Stirling, died on the 23rd

February, 1817, in his 77th year and the 43rd of his ministry. Of

somewhat uncouth aspect, with a stern and gloomy countenance, he was

a fearless and most effective preacher. In his poem of "The Twa

Herds," the poet Burns has celebrated him thus:-

What herd like Russel

tell'd his tale;

His voice was heard through muir and dale."

And in the "Holy Fair," in these lines:-

"His piercin' words, like Highland swords,

Divide the joints and marrow

His talk o' hell, whare devils dwell,

Our vera saul does barrow."—Ed.

A contemporary of my

father, under Mr. Russel's tuition at Cromarty, was Charles Grant,

one of the directors of the E. I. Company, member of Parliament for

Inverness-shire, and father of Lord Glenelg. He was then a shop-lad

in the employment of William Forsyth, an enterprising merchant. How

long my father remained at the school of Mr. Russel I do not

recollect. His father came frequently to see him, and took a lively

interest in the progress of his education and in the moral culture

of his mind. Iie went to the Aberdeen University in 1776, and

prosecuted his studies at King's College. One of the professors, Ir.

Thomas Gordon, was a model of Scottish scholarship. Latin was his

element, the classics his friends; while his minute knowledge of the

language of Rome, unbalanced by an enlarged mental quality, rendered

him a pedant. He loved to express himself, not only to his students,

but to his friends, in the correct and studied periods of Sallust,

or Cicero, or Livy. The students called him "Jupiter." One of my

father's class-fellows was Duncan Munro of Culcairn. This gentleman

was pervaded with an inexhaustible fund of drollery, in which he was

wont to indulge at the risk of a broken head. May father, on one

occasion, was one of those who, for "value received ' at the hands

of Duncan, was able and willing to repay him. The students of King's

College had a ball or dance in the College lobby every Saturday

evening. At this dance, on one occasion, my father, a tall, gaunt

lad; was practising his steps, when his activity, exhibiting far

more strength than grace, attracted Munro's notice. He was holding

an orange between his thumb and forefinger, when he cast his eye on

my father; the sense of the ludicrous got the advantage of hint, and

he sent the orange at my father's head with such dexterity that,

after hitting him on the nose, it bounded to the top of the room,

with the result that all the party laughed merrily. Calculating the

consequences, Culcairn took to his heels, while my father gave

chase—down the lobby stair, out at the entry, twice round the

court-yard, until at last Culcairn, scrambling quickly over the

court-wall, got off. This facetious gentleman was heir to the estate

of Foulis. He was also connected with George Ross of Cromarty; and

his son, had he lived, would have succeeded, on the death of the

present baronet of Foulis, both to the estates of Cromarty and

Foulis. Culcairn sold his paternal property to clear off

incumbrances on the estate of Cromarty, and lived at Cromarty House,

where he died in 1820.

Having finished his

classical studies my father, on the death of my grandfather, removed

from Ross to Strathnaver in Sutherlandshire; his mother went with

him. His sister Catherine was there before him, married to Charles

Gordon of Pulrossie. They took up their abode at Clerkhill, in the

immediate vicinity of the Parish Church of Farr. Charles Gordon was

a native of the parish, descended from that branch of the clan

Gordon which originally came to Sutherland along with Adam, Lord

Aboyne, second son of the Earl of Huntly. The place of Clerkhill lie

occupied as a farm; he was besides factor on the Reay estate, and an

extensive cattle-dealer. He was twice married; by his first wife he

had no family. By his second wife, my father's eldest sister, he had

three sons and two daughters. John, the eldest, succeeded to the

family estate; William, the second son, lived after his return from

the American war at Clerkhi]l, and George at the farm of Skelpig, on

the north bank of the Laver. His eldest daughter, Fairly, married

James Anderson of Rispond, in Durness. His younger daughter married

an Englishman named Todd, and thus gave offence to her friends, as

her husband was obscure and indigent. But in London Mr. Todd got

into business, and afterwards became affluent.

Charles Gordon took a

lively interest in my father's welfare, and, he is one of the most

influential men in the Reay country, he had much in his power. To

his friendship and influence, under God, my father was indebted for

every situation which he held in that country. His first appointment

was that of parochial schoolmaster of Tongue, a situation which he

held until lie received license. When he went to Tongue his mother

accompanied him. There she died, and was buried in the tomb of the

Scouries.

The Reay country, or

"Duthaich Mhic Aoidh," extending from the river Torrisdale to the

arm of the sea dividing it from Assynt to the west, was the

territory of the clan Mackay, of which Lord Reay was chief. When my

father first came to reside in that country, Hugh, sixth Lord Reay,

bad, six years before, succeeded to the title and estate on the

death of his brother George. In early youth he showed no symptoms of

that weakness on account of which it was found necessary to place

him under a tutor for the efficient management of his estate. He

made progress in his studies, and had a great taste for music. When

his intellect gave way, he was lodged in the house of a clansman, a

relative of my father, James Mackay of Skerra, where he continued

until his death, which took place in 1797. His first tutor was his

paternal uncle, Colonel Hugh Mackay. of Bighouse, second son of

George, third Lord Reay. On his death, George Mackay of Skibo, his

brother, and third son of George, Lord Reay, was appointed. It was

during the tutorage of Mr. Mackay of Skibo that my father came first

to the country as schoolmaster of Tongue. George Mackay was a man of

note in his time, but choleric and hasty in his temper—a propensity

which has markedly characterised the whole race of the Mackays. He

was also improvident and extravagant, while his wife, the

granddaughter of Kenneth, Lord Duffus, was not more careful. To be,

during the nonage of the proprietor of a large estate, what was

usually called the "Tutor," was, in those days, tantamount to being

the actual owner. Yet, with all this advantage, George Mackay of

Skibo died a bankrupt. At his death everything went to the hammer,

and so completely stripped was his family that his children were

conveyed from the castle of Skibo in cruppers on the backs of

ponies. Mackay of Skibo, during the minority of Elizabeth, Countess

and Duchess of Sutherland, was returned member of Parliament for

that county. His Parliamentary career was distinguished by a

persistent taciturnity. How he came to be proprietor of Skibo I

cannot say. I am inclined to think that it was a part of the

property belonging to the Reay family within the limits of the

Sutherland estate, and was gifted to him by his father. After the

present Lord Reay succeeded to the inheritance of his ancestors, it

is said that he could never pass the manor of Skibo, then in

possession of the Dempsters, without shedding tears. " It would have

been my principal residence," he used to say, "and would have suited

me so well, had my father had but common sense." But his lordship

was at least equally deficient in common sense, as the recent sale

of the Reay estate so clearly proves. Col. Hugh Mackay of Bighouse

was elder brother of George Mackay of Skibo, and preceded him in the

tutorship. He became proprietor of the estate of Bighouse in

consequence of an arbitrary stretch of chieftain power by his father

George, third Lord Reay. The estate of Bighouse for four generations

was the hereditary patrimony of a family of the name of Mackay,

lineally descended from William, youngest son of Mr Mackay of Farr,

chief of the clan. The last of the proprietors of this family was

George Mackay of Bighouse, who bad a son, Hugh, and two daughters,

Elizabeth and Janet. Hugh their brother died young, and his

surviving sisters became co-heiresses of the estate of Bighouse.

Elizabeth, the elder, married Colonel Hugh Mackay, and Janet

espoused William Mackay of Melness, the lineal descendant and

representative of Colonel Eneas Mackay, a younger son of Donald,

first Lord Reay. On the death of George Mackay, last laird of

Bighouse, the estate came to be divided between his two surviving

children, Mrs. Col. Hugh Mackay, and Mrs. Mackay of Melness. Lord

Reay, however, got the property settled on the elder sister, to the

exclusion of the younger. This proceeding was resented by William of

Melness, and being a man of as much resolution as he was hot and

choleric, he resolved not tamely to submit to the injustice. Having

ascertained that his chief was at home, Melness armed himself with

his claymore, secured by a strong leathern belt round his loins, to

which was added a pair of loaded pistols. Thus accoutred Melness

crossed the Ferry below Tongue, and directed his course to the

residence of his chief. Demanding entrance he was admitted to the

parlour. ' His lordship received him with smiles, begged he would be

seated, and asked him the news of the day. "My Lord," said Melness,

"I have come to demand at your hands my just rights. My wife is

co-heiress of the estate of Bighouse, and I know," he added, raising

his voice to a. wrathful pitch, "I know that you have the titles in

your possession, and that—that—you're scheming to denude me and my

wife of our share that your son Hugh may have it. I'll not allow

this; I demand the title-deeds and the will of my father-in-law."

Lord Reay attempted to parry him off with friendly assurances. At

length, Melness got furious. "My Lord," said he, "I am not now to be

trifled with," and, striding to the room door, securely bolted it.

"Take your chance," said he, "either produce the will and the

title-deeds or take this," and pulling out his loaded pistol, he

placed it full cocked within four or five inches of his lordship's

breast. Matters had become serious, and the chief waxed pale. "Melness,"

he exclaimed, "since you must have the papers you ask, will you

allow me to go for them, they are in the strong box in my

writing-room above stairs?" Melness assented, and his chief walked

out at the parlour door and tripped upstairs. His lordship, however,

had no sooner put a strong door doubly bolted, and a double pair of

stairs between him and his kinsman, than lie took other measures.

Opening the window, he called to his footman, whom he saw in front

of the house, instructing him to request Mr. Mackay of Melness, whom

he would find in the parlour, to come out and speak to him. The

message was delivered, and on Melness making his appearance in the

close, Lord Reay called from the window, "William, go home and

compose yourself, the papers you'll never handle." Closing the

window, he put an end to all further conference. Lord Reay's son got

possession of the property, and his removal from the Reay country to

reside at Bighouse took place soon thereafter. [Rob Donn, on that

occasion, composed one of the ablest effusions of his poetic muse.

It is one of the most graphic and complete hunting songs in any

language.] These occurrences happened long before my father came to

that country. William Mackay of Melness flourished in 1727, and must

have been dead either before my father was born, or when he was a

child. During my father's residence in the Reay country, George

Mackay of Skibo was, as tutor of Reay, succeeded by his brother,

General Alexr. Mackay, after whose death, George Mackay of Bighouse

filled the office, and continued to do so until Lord Reay's death.

The leading men in the Reay country were all members of the clan

Mackay, and descended from the principal family. They held farms by

leases, or on tradset, that is, until the proprietor redeemed the

land by paying up a sum advanced on mortgage.

The most

distinguished of the Mackays of that age was "Rob Donn" the poet.

This unlettered, but highly-gifted, individual was born in the year

1714, at Alt na Caillich, Strathmore, parish of Durness. From his

early years his rich and original poetic vein was strongly

exhibited. His poetry was the plant, not in its improved and

cultivated, but in its natural state, growing in its first soil, in

wild and inimitable simplicity. Even Burns himself, high as his

claims are, must yield to Rob Donn. Burns and all his great poetic

compeers could read and rightly estimate the poetry of others. Rob

Donn could neither read nor write. He stood alone. With a poet's eye

be looked into the face of nature. Nature in its fairest or in its

most abject forms, whether animate or inanimate, rational or

irrational, was at once his theme and his study. In his poetry there

is a variety of subjects embracing all the incidents of common life.

His poetry is history—a history of everyone and everything with

which he at any time came into contact in the country in which he

lived. His descriptions do not merely let us know what these things

or persons were, but identify us with them; we behold them not as

things that were, but as things that are. They are all made to pass

in review before us, in their characters, and language, and

peculiarities, and habits. His Elegies open a fountain of sadness.

They bring us to the house of mourning, they place us by the dead

man's bed, and compel us to feel a sinking of heart in sympathy with

every member of the family at the breach that has been made, His

love songs are chaste and inimitably tender. In his satires every

vulnerable point, whether a moral deformity or a bodily defect, is

seized upon, laid bare, and subjected to the lash, every stroke of

which draws blood, and not one of which misses its aim. Unlike many

poets of eminence, he is the advocate of religion. Then and for many

years after his death, the only library in which his poems were to

be found was the memory of the people. When he composed a song, he

no sooner sang it than, with all the speed of the press, it

circulated throughout the country. An edition of his poems was

published in 1829, under the revision of Dr. Mackay of Dunoon; but

it is singularly defective. The editor was anxious to .give Rob Donn

universal publicity in the Highlands by correcting his Gaelic; but

being, unfortunately, no poet himself, he, in his attempts to

improve the poet's Gaelic, has strangled his poetry. My father, when

schoolmaster of Tongue, met with the poet. He invited him to dinner,

an invitation which was accepted. The poet was pleased with his fare

and still more with his host, and, at parting, offered to make his

entertainer the subject of a poem. This offer my father declined,

aware of those high powers of satire with which his guest was

endowed, and which, like a razor dipt in oil, never cut so keenly as

when intermingled with compliment and praise. Rob Donn died in 1778,

at the early age of sixty-four. A monument of polished granite was,

by subscription, erected to his memory in 1829, in the churchyard of

Durness, his native parish. A monument far more in keeping with the

originality and simplicity of his character was placed upon his

grave by his surviving friends soon after his decease—a rude,

unpolished slab, containing no other inscription than the two

emphatic words "Rob Donn."

That which chiefly

distinguished the Reay country in my father's time was its religious

society. The ministers who constituted the Presbytery of Tongue were

eminent for piety. The minister of Parr, Mr. George Munro, a man of

great worth and Christian simplicity, was married to my father's

maternal aunt Barbara, third (laughter of John Mackay, minister of

Lairg, by whom he had a daughter Mary. She was, after her father's

death, housekeeper to her uncle, Mr. Thomas Mackay, at the Manse of

Lairg, and after his death, resided at Dornoch. Her father, Mr.

George Munro, was one of the most-honoured and useful ministers of

his day. Previous to his settlement at Farr, lie was missionary at

Achness in the upper part of the parish, and there he began his

ministerial labours at an early age. When he first came among the

people of the district they were disposed to "despise his youth." A

pious man applied to him for baptism for his child. Mr. Munro came

to the mans house to celebrate the rite. While preparations were

making for the ordinance, Mr. Munro began to play with one of the

children. He fenced with the boy with a rod which he had in his

hand, and chased him round the room. The pious father was so shocked

at this apparent levity, that he had almost resolved not to receive

baptism at his hands. The service, however, was commenced, and

before the conclusion Mr. Munro so clearly and scripturally laid

down the nature of the ordinance and the sum of parental

obligations, that the man declared he was overwhelmed with shame

that he ever allowed himself to harbour any unworthy suspicions of

his visitor's ministerial zeal. His ministry at Achness and

afterwards at Farr was signally blessed. Some of the most eminent

Christians who subsequently made Strathnaver another Bethel were the

fruits of it. Mr. George Munro was ordained minister of Farr in

1754; he died in 1775, at the age of seventy-four.—Ed.

Two other eminent

members of the Presbytery of Tongue were Mr. John Thomson, of

1)urness, and Mr William Mackenzie, of Tongue. Mr. Thomson was a

native of the parish of Avoch in the Black Isle. When settled

minister of Durness, he was deficient both in Gaelic and in sound

theology. The former defect he never overcame; not so, however, with

regard to his theology. He had not been many years minister of

Durness when it underwent a decided change. His doctrine, at first,

had been a mixture of law and gospel, grace and good works, not,

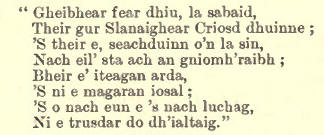

however, placed in their proper and scriptural relation. Rob Donn,

in a poem which he composed on the clergy of a former generation—the

predecessors of those who have been named—remarks that "one of them

may be found who on Sabbath day will assert that Christ is our

Saviour, but who a week after will declare that there is no profit

but in works; at one time he will fly so high and, anon, he will

creep so low that, being like neither a bird nor a mouse, be makes

of himself a filthy bat."

Mr. Thomson at first

preached in such a strain as this, and, having neither the powers of

oratory nor of mind to shape his doctrines into a regular system,

nor anything like intelligible language to convey it, his preaching

was rejected by the pious and scoffed at by the profane. Having

preached a sermon on one occasion at Eriboll, a place within the

boundaries of his parish, some of the best and most eminent

Christians among his hearers were highly dissatisfied. At a

fellowship meeting held at the same place next day, at which Mr.

Thomson presided, they resolved to give out a question bearing on

his doctrine. It was taken up and discussed. Mr. Thomson saw their

device, and, highly offended, dismissed the meeting. The attack,

however, led him to reflect and to test his own views by the

Scriptures, the result being that, after many private conferences

with his co-presbyter, Mr. William Mackenzie, he retracted his

erroneous opinions, eagerly embraced the gospel, and preached it to

his people. He became thereafter a zealous and devoted servant of

Christ, and, to the close of his life, was a most exemplary pattern

of that "simplicity and godly sincerity" by which the Spirit of

Christ is most clearly manifested. He died in 1811, and was

succeeded by his son-in-law, Mr. William Findlater, who was inducted

in 1812. Mr. John Thomson was a man of great Christian simplicity,

but very peculiar in his manner. When be preached, or when he

expressed himself keenly in any argument, he had an odd habit of

spitting in his fist. His powers of utterance, especially in the

Gaelic language, being very limited, he made much use of his hand

when he spoke to enforce what he did say. lie was the immediate

successor of Mr Murdoch .Macdonald, the patron and warmly-attached

friend of Rob Done, with whom, however, Mr. Thomson was by no means

such a favourite. The bard, though prejudiced against Mr. Thomson,

could not but respect him. But the brother of the minister could not

escape the wit of Rob Donn in one of the bitterest of his satires is

hurled at the head of poor Lewis Thomson.

In 1769 Mr. William

Mackenzie succeeded 24r. John Mackay as minister of Tongue. Previous

to his settlement in that parish he was missionary of Achness,

having succeeded Mr. Munro of Farr in that charge. He was a lively,

eloquent preacher of considerable talent and fervent piety, also of

a fine personal appearance. He was much beloved at Achness, and no

less so by the parishioners of Tongue, among whom he laboured for

upwards of sixty years. While at Achness he married Jean, daughter

of the Rev. William Porteous of Rafford, a near relative of the

eminent John Porteous of Kilmuir-Easter in Ross-shire. She was a

woman of considerable accomplishments, and a great talker. Her

husband was also rather loquacious, and, when they were both

present, whether at their own hospitable board or elsewhere,

conversation was not allowed to flag. They not only engrossed the

whole of it, but went full tilt against each other, for the purpose

of talking one another down, especially when they both resolved to

tell the same anecdote. It was the practice in those days for the

people to bring presents to the minister, consisting entirely of

eatables, such as butter, cheese, and mutton. Mr. Mackenzie was

loaded with such gifts. On one occasion, when he was at Achness, as

lie used to relate, lie had gone out in the forenoon to visit his

people. Upon his return he came in to witness an amusing spectacle.

The floor of their little parlour at Achness he found covered with

six wedders, each of which was flanked with parcels of fresh butter,

cheese, and baskets of eggs. Six honest housewives, the donors and

bearers of these presents, were placed, side by side, on a form

close by the wall. His wife stood in front of them, and laboured

hard to do the honours of her house. It was, however, rather a

puzzling task. She could speak no Gaelic, and not one solitary

syllable of English did they know. But she was determined not to

stop at this rather formidable obstacle. She produced meat and

drink, the best the house could afford, and began and ended the

repast by a round of kisses, beginning at the first and ending at

the last of them, being the only way by which she could make them to

know that they were heartily welcome to their lunch, and that she

was grateful for their presents. Coming to her relief, Mr. Mackenzie

spoke to them in language which they could better understand. [Mr.

William Mackenzie was admitted to the parish of Tongue in 1769; he

died in January 1534 at the ago of ninety-six, in the 67th year of

his ministry.—Ed).]

As a teacher, my

father had three distinguishing qualities—assiduity, fidelity, and,

I must add, severity. The last of these arose from a hasty temper

and his own early training. My father's temper was hot, but it was

connected with that generosity which makes kind-hearted, hasty men

the favourites of those who personally know them. His natural heat

of temper too was the more formidable inasmuch as it was combined

with a more than ordinary measure of personal strength. lie was six

feet one inch in height, with great breadth of chest and shoulders.

To his scholars therefore his temper when ruffled was no trifle. Let

me do him only justice, however, by saying that, it was never called

forth but by carelessness, disobedience to authority, or vice—in

short, by any of those things which thoughtless youth are so ready

to throw as obstacles in the way of their own progress or

improvement. To remove these obstacles he subjected his pupils to

strict discipline, and the heat of temper with which he did so was

expressive, not of any ill-will towards the offenders, but of

anxiety that the ends of discipline should be secured. On one

occasion his severity excited a mutiny. His pupils combined to pay

back in kind some very hard knocks which some of them had received.

In those days scholars were not invariably schoolboys. Many attended

his school who were nearly as old as himself, and some of them of

considerable strength. At the head of the conspiracy were, of

course, the strongest of them. They had agreed that on the first

occasion when any boy was flogged, a simultaneous attack should be

made upon the master. The occasion they anticipated soon offered

itself. One of the scholars was called up to account for some

misdemeanours, and was convicted. But just as the master was in the

act of inflicting punishment, the mutineers rushed out of their

seats and attacked him. The onset was so sudden, and on his part so

unexpected, that, for a moment, he offered no resistance. But his

apparent passiveness was but as the calm which is the prelude to the

storm. With his ponderous arm he dealt heavy blows on his

assailants, and, in a few minutes, cleared the schoolroom. The

lesson of subordination which he so impressively taught was not

forgotten so long as lie filled the office, and lie received from

his pupils ever afterwards an implicit obedience. One of the

ringleaders was Hugh Mackay, a native of the parish of Tongue, who,

in 1793, became minister of Moy, Inverness-shire. Mr. Mackay was

known as a decided and deeply-exercised Christian. He was the

intimate friend in Christian fellowship and ministerial labour of my

uncle, Dr. Fraser of Kirkhill. He died in 1804, amidst the

lamentations of his flock.

Though my father's

severity was resented by some, yet he was a favourite with others,

and indeed ultimately with all his pupils. After passing the usual

preliminary trials before the Presbytery of Tongue, lie was by them

licensed to preach the gospel on the 2nd of April, 1779. He now

resigned the school, and was employed for several years as assistant

to the Rev. Alexander Pope, minister of Reay, which office he held

until Mr. Pope's death in 1782. When he assisted Mr. Pope, he

resided, in the capacity of private tutor, in the family of his

relative, by the mother's side, and the principal heritor of the

parish, George Mackay of Bighouse. Mr. Pope was a native of

Sutherlandshire. His father was the last Episcopal minister of Loth,

and he was the lineal descendant of Charles Pope, Episcopal minister

of the parish of Kirkmichael. now united with Cullicudden. Another

of his ancestors, William Pope, was precentor of the Cathedral of

Dornoch, of whom Sir Robert Gordon, in his history of the family of

Sutherland, supplies some notices. Alexander Pope was the eldest son

of a numerous family of sons and daughters. He had been most

liberally educated, and being himself a man of more than ordinary

talent, he made a corresponding use of his advantages. He was an

accomplished classical scholar, an intelligent antiquary, and was

intimately conversant with science. [Mr. Pope was an accomplished

antiquary; he contributed materials to Mr. Pennant, in relation to

Strathuaver, Caithness, and Sutherland, was a writer for "Archaeologia

Scotiea," and translated a portion of the "Oreades" of Torfaeus.—Ed.]

When a young man he became acquainted with his namesake, Alexander

Pope, the poet. He went to England purposely to visit this

celebrated man. Their meeting at first was rather stiff and cold,

arising, it is believed, from his having taken the liberty of

calling in travelling attire. After he had come in contact with the

strong and well-furnished intellect of his Scottish namesake,

however, the poet relaxed, and their intercourse became cordial.

Their correspondence was kept up. A copy of his poems, published in

1717, the poet sent to his friend at Reay, which, at the auction of

Mr. Pope's books, after his death, was purchased by Mr. Thomas

Jolly, minister of Dunnet. Mr. Pope was settled at Reay in 1734. He

was a man of extraordinary strength, fervent piety, and unflagging

zeal. His parishioners, when he was first settled among them, were

not only ignorant but flagrantly vicious. Like the people of

Lochcarron, they were Episcopalians in name, but heathens in

reality. Mr. Pope soon discovered that they required a very rough

mode of treatment, and being from his strength furnished with a

sufficient capacity to administer any needful chastisement, he

failed not vigorously to exercise it. He usually carried about with

him a short thick cudgel, which, from the use he was compelled to

make of it, as well as from a sort of delegated constabulary

authority he had from Sinclair of Ulbster, the Sheriff of the

county, was known as "the bailie." One Sabbath evening, after

preaching to a small audience, he sat down on a stone seat at the

west end of the manse. About a hundred yards distant stood a small

hut used as a tavern. Mr. Pope soon observed that the inn was better

attended than the church had been, and discovered among those

visiting it a number of his parishioners, whose little measure of

sense and reflection was overpowered by the fumes of the liquor in

which they had indulged. As he was revolving in his mind what he

should do to break up this pandemonium, two stout fellows from the

crowd moved towards him. On coming up, they said that they were

requested by their companions to ask him to come over and join their

party. Mr. Pope declined the invitation, and told them that, while

he commended their hospitality, he was very much grieved at their

conduct in thus employing the day of sacred rest, instead of

engaging in the services which God had enjoined. He accordingly

exhorted them to disperse. "You are most ungrateful," said the

deputies, "to refuse our hospitality, and if you think that we are

to give up the customs of our fathers for you, or all the Whig

ministers in the country, you'll find yourself in error. But come

along with us, for if we repeat your words to our neighbours they'll

call you to such a reckoning that you will be wishing you had never

uttered them." Mr. Pope told them that he spoke the truth, that the

truth he would never retract, that he was accountable to God, and

that, in the path of duty, he never saw the man, or number of men,

that would daunt him. Hearing this the men set off at a round pace

to join their associates. In a few minutes after their arrival the

inmates of the tavern turned out, and Mr. Pope saw nearly a dozen

strong, able-bodied men advancing upon him, not so drunk that they

could not fight, nor yet sober enough to refrain from so doing.

Guessing their intentions, Mr. Pope rose from his seat, placed his

back to the wall, grasped " the bailie," and stood firm. The

foremost of the gang held in his hands a bottle and glass. When

within three feet of Mr. Pope, he deliberately filled the glass,

asked the minister to drink, and told him that it would be far

better for him to warm his heart with a glass of whisky than, by

refusing, to risk the safety of his head. Mr. Pope refused, and

again renewed his remonstrances against such practices on the Lord's

day. This was the signal for battle. The fellow now threw the bottle

towards the minister's head, when Mr. Pope prostrated him by a

stunning blow with his baton. Three or four strong savages next came

forward in turn to avenge the fall of their companion, but these,

one after the other, succumbed under the weight of "the bailie"

vigorously applied. The rest of the gang soon beat a hasty retreat,

carrying with them their wounded companions.

Mr. Pope visited his

parishioners, when first settled amongst them, in the disguise of a

drover, pedlar, or stranger on a journey, asking lodgings and

hospitality, which in those days were never refused even by the

rudest. On one occasion, after partaking of hospitality, lie by main

force compelled his host to allow family worship to be conducted.

When the poor man discovered that his guest was his minister, he was

much impressed; ever afterwards he kept family worship himself,

became a devout man, and was subsequently ordained as an elder. Mr.

Pope chose as elders, not only the most decent and orderly, but also

the strongest men in the parish, the qualification of strength being

particularly necessary for the work which they often had to do, and

which was performed on what Dr. Chalmers would have called the

"aggressive principle." A very coarse fellow, occupying a small

farm, kept a mistress, by whom he had two children. Cited to appear

before the Session, he obeyed the summons, and, in a few words, made

his statement of the case. Mr. Pope pointed out to him the

sinfulness of his conduct, and insisted that, in conformity to the

law and discipline of the Church, he should make a public profession

of his repentance, by appearing before the congregation on the

following Sabbath to be rebuked. "Before I submit to any such

thing," said the farmer, "you may pluck out my last tooth." "We

shall see," replied the minister, dismissing him. This Session

meeting was held on a Monday, and it was agreed, before the close,

that three of the strongest elders should repair to the farmer's

house next Sabbath morning, and forcibly bring him to church. When

Sabbath came this was done. The elders went to the man's house about

ten o'clock, and, after a stout conflict, he was mastered, bound

with a rope, and marched to church. One of the elders now went to

Mr. Pope for further instructions. "Bind him to one of the seats

before the pulpit," said Mr. Pope, "and sit one of you on each side

of him till the service is finished." His orders were obeyed. At the

close of the service, before pronouncing the benediction, Mr. Pope

rose to reprove the offender. "You told us," said the minister,

"that we might pull the last tooth out of your head before you would

submit to be where you are, but," pointing his finger in scorn at

him, and uttering one of the most contemptuous sounds with his

breath between his lips, which can better be imagined than

described, he added, "Poor braggart, where are you now?" The address

was in Gaelic. The fellow duly served discipline, but the epithet

applied to him on this occasion stuck to him for life, and to his

family for several generations.

During the course of

his ministry, many of Mr. Pope's parishioners advanced in the

knowledge of the truth, and also in the arts of civilised life. Ale

and whisky drinking was discontinued on the Sabbath evenings, though

too much indulged in on week days. One evening the landlady of the

tavern came to him with the complaint that six men from a distance,

who had come in the forenoon, had continued drinking ever since,

that they refused to leave, and were now fighting with each other,

and that she was afraid they would break all her furniture, and set

the house on fire. After reproving her for keeping so disorderly a

house, Mr. Pope directed her to get a ladder and place it against

the back wall of her dwelling, to fill so many tubs of water,

leaving them at the foot of the ladder, and to await his coming. All

this was done, and in about half-an-hour thereafter, when the topers

were holding high carnival within, Mr. Pope, seizing one of the

tubs, mounted the ladder, and, sitting astride the roof, removed

some thatch and turf, and emptied the contents of the tub upon the

Bacehanalians below. This was followed by a. second and a third

down-pour as quickly as Mr. Pope could be furnished with tubs of

water from below, with which he was readily supplied by the active

co-operation of the landlord and his wife. The consequence of this

ready method with the drinkers may be easily conceived. Their coats

were drenched, and, like as many bulldogs under similar treatment,

they let go their hold of each other and rushed out. Coming to

understand, however, that the landlord and his wife had a hand in

the matter, they were about to deal with them rather roughly; but

Mr. Pope had already descended from aloft, and, with "the bailie" in

his hand, stood beside them. It was enough, they all scampered off.

Mr. Pope made an

annual practice of visiting his people and catechising them. When

thus engaged he sought particularly to impress on his parishioners,

especially the heads of families, the duty of holding family

worship, giving them directions how they should proceed, and, in his

subsequent visits, questioning them whether they had or had not

followed his directions. Coming to the house of one William

Sutherland, at a place called Caraside, he questioned him on this

important duty. Sutherland answered that he was not in the habit of

keeping family worship, as lie had no prayers, "but my goot parson,"

he added, "gin ye give me a twelvemonths after this day, by the time

ye're coming roun' amang us the next year, I'll be ready for you."

To this proposal Mr. Pope agreed, and at about that time next year

lie called at Caraside. "Weel, minister," said Sutherland, "I'm

ready for ye now," and, without further prelude, he went down upon

his knees, and uttered aloud a long Gaelic prayer. Scarcely had the

last syllable ceased on his lips, when he started up again, and

said, "Now, sir, what think ye of that?" "O, my friend," Mr. Pope

replied, "it will never do; you must begin again if you would learn

to pray aright." Sutherland was amazed. "It won t do, do you say,

sir; I have spent a whole year in making up that prayer, and rather

than lose my labour, if it winna do for a prayer, I'll break it

down, and make two graces of it." And Sutherland was true to his

word; to the day of his death the blessing before meat was implored

in the words of the first part of his prayer, and thanks returned in

the words of the second.

Mr. Pope was a rigid disciplinarian, so much so as to induce many,

who had rendered themselves liable to discipline, to become

fugitives from it. On one occasion he had, at the close of the

service, to refer to an individual, who, from his conduct, had

fallen under the ban of his Session, but dreading the severity of

the tribunal before which he had to appear, had absconded. Mr. Pope

was very indignant, and said that, hide himself as he chose, he

would find him out; "yes,' he added, " and should he go to hell

itself, I'll follow him, to get him back." Mr. Mackay of Bighouse

was in the church, and, after the service, he called at the manse.

Addressing Mr. Pope, he said, "I have called upon you to-day, sir,

to bid you farewell, before you set out on your perilous journey."

"What do you mean, Bighouse?" said Mr Pope. "Oh, you told us

to-day," said Mr. Mackay, "that you were to set out in pursuit of an

evil-doer, and that you would follow him even to hell." "Don't jest,

my good friend, on a subject that eternity will make serious

enough," replied Mr. Pope; "hell is the place appointed, no doubt,

for all evil-doers in eternity, but the ways of sin and its

delusions are hell on earth, and if I follow the sinner, with the

word of God and the discipline of the church, into all his attempts

to hide his sin, I go to hell for him, and, if successful, from hell

I shall be instrumental in bringing him back."

Towards the close of

his life, Mr. Pope lost the use of his limbs, and, for some time,

was carried to the pulpit in a sort of litter. His son James, who

had gone through the usual course of study for the church, was

licensed to preach, and was, in 1779, admitted as his father's

assistant and successor. He was a young man of very superior

talents, and of decided piety, and gave every promise of being the

worthy successor of so good a father. But he died soon after his

ordination, sorely lamented by his father and all the parishioners.

It was in consequence of this that my father became his assistant,

which he continued to be until Mr Pope's death in 1782.

When the parish

became vacant my father's friends made every exertion to procure him

the succession. The living was in the gift of the Crown, and due

application was made by his friends, Mr. Mackay of Bighouse and Mr.

Gordon of Pulrossie, warmly seconded by a great majority of the

parishioners. These, however, were not the days of popular

settlements, and the application was not successful. George Mackay,

a ferryman at Bonar, had a son. David, who was a preacher, and this

young man was recommended to Mr. Mackay of Skibo, the tutor of Reay

and Member for Sutherland, who made him his protege. Mr. David

Mackay was, through his interest, presented to the parish, and

admitted minister of Reay in 1783. He was a worthy, pious man, hut,

during his incumbency of fifty-one years, he was unable to effect

much good in his parish. Soon after his settlement he became an

invalid. He suffered from a nervous disorder which, though it did

not interfere with his physical health, totally unfitted him for the

discharge of his ministerial physical with the exception of

preaching every Sabbath.

He laid down some

rules, however, whereby to regulate both his diet and his physical

exercise, and, by a strict adherence to these, he succeeded in

turning his imaginary ailments into the most efficient means of

preserving his health and prolonging his life. He died when upwards

of eighty years of age.

Mr. David Mackay,

minister of Reay, was noted alike for his piety and literary

industry. So early as four in the morning he commenced his studies

daily. He was particularly remarkable for fostering rising merit,

and in bringing forward, from humble life to stations of usefulness,

young persons of ability. He died in 1835, at the age of eighty-four

years.—Ed). |