|

1822-24.

WE left Aberdeen in

the month of May, 1822, by coach for the north. We were accompanied

by my wife's sister, Frances, her mother, and other sister, Maria,

choosing to go before us by sea. We came that evening to Nairn. Our

fellow-passenger was Capt. Robert Mackay, Araichlinni's son, who

left us at Nairn on his way home, after dining with us at Forres.

Next morning we hired a coach at Nairn to Resolis, crossed the

Fort-George ferry, and arrived there in good time next day. We found

Airs. Robertson and Maria before us. The meeting was a joyful one,

but it was mingled up not a little with a gloom which hung over us,

we could not tell how.

Shortly thereafter,

my induction took place within the church at Resolis. All the

members of the Presbytery of Chanonry were present. These were,

Messrs James Smith of Avoch, Roderick Mackenzie of Kilmuir-Wester

and Suddy, Robert Smith of Cromarty, John Kennedy of Killearnan, and

Alexander Wood of Rosemarkie. My father was also present, and Dr.

John MacDonald of Urquhart or Ferintosh. Mr. Roderick Morrison,

factor for Newhall, was there also, and remained to a late hour in

the evening. The services of the day were conducted by Mr. Kennedy

of Killearnan, and throughout the whole service, from first to last,

he "approved himself to the consciences of all" as the servant of

the Lord. The service ended, the Presbytery dined, at my expense, at

the inn at Balblair, where we passed the time agreeably enough, the

men of every age associating and closely drawing up with each other.

I cannot dismiss without a short notice the venerable minister who

officiated on this day. Mr. Kennedy of Killearnan had bug been an

eminent father in the Church of Christ, and throughout his ministry

his work had been acknowledged by his Heavenly Master. His

settlement had been a most harmonious one in so far as the

parishioners were concerned, but a very violent one as regards the

Presbytery. The gloom of Moderatism rested upon the Church in that

part of the country, and Mr. Kennedy's settlement was dreaded as the

breaking in upon it of a new day. He was not an orator in any sense

of the term, nor was he a scholar, for his early education had been

neglected. But he was thoroughly imbued with the spirit of the

Puritan divines, and of some of our own old Scottish preachers. The

leading features of his ministerial and personal character were

piety and prayer, the one the necessary off-shoot of the other. His

closest preparations for the pulpit, and for the week-day discharge

of the duties of the ministry, chiefly consisted in prayer. As the

close of his life drew near, his cries for divine help became more

urgent, and more frequent and importunate, so that prayer became, at

last, the great and leading business of every (lay. After a ministry

of 43 years, he died in 1841, aged about 70 years.

Mr. Robert Arthur was

my immediate predecessor in the charge of Resolis, where he laboured

for forty-seven years, and if his life and ministry were anything

but what they should have been, it was not for the want of a bright

example clearly set before him of one who, as a Christian man and a

gospel minister, had adorned the doctrine of God his Saviour. This

was Mr. Hector MacPhail whom he succeeded.

Mr. MacPhail was

truly a man of God, for whom "to live was Christ." He was perhaps

one of the most deeply-exercised Christians of his time, equally and

minutely conversant with the depths of Satan on the one hand, and

the "unsearchable riches of Christ" on the other. His faith, to

himself scarcely perceptible, was great in the sight of the Searcher

of Hearts—winging its flight upwards, like the eagle's towards the

Sun, whose ineffable light, instead of obscuring its gaze, served

only to strengthen and enlarge its capacity of spiritual

apprehension. But this faith took its rise from a sense of utter

hopelessness of help in man to save, and it made its way to " that

which is within the veil," through the darkness of unbelief, and in

the face of Satan's deepest devices to ensnare and deceive.

His first

introduction to his future charge was by means of an "elect lady "

then residing in the parish, Lady Ardoch, otherwise Mrs. Gordon of

Ardoch, now called Poyntzfield. He was settled over the united

parishes of Kirkmichael and Cullicudden, 22nd September, 1748, and

continued to labour fervently, zealously, and successfully in word

and in doctrine for twenty-six years thereafter. His residence, for

the first seven years, was in the manse of Cullicudden, and he

preached alternately in the church there and in that of Kirkmichael

at the other end of that parish. The manse and both churches,

however, became ruinous, and were besides inconveniently situated.

The heritors and Presbytery resolved therefore to select a more

central situation, and accordingly made choice of a small farm

situated at the western extremity of the old parish of Kirkmichael,

called Re-sholuis, or the ridge of light. Here they erected a manse

and a church, each about double the size of the old ones, and the

united parishes, though individually retaining their ancient names,

have ever since been known, quoad sacra, under the name of Resolis.

During the earlier

part of his ministry Mr. MacPhail was much tried with strong

temptations to atheism. But, soon after he came to reside at Resolis,

and after a longer than ordinary period of depression of mind, be

was, through the Word and the Spirit and the Works of God, for ever

delivered from its grasp. He was of the happy number who, "in the

day of power," had their minds humbled to the simplicity of

children, and who, receiving the truth as such, gave God full and

implicit credit for truth in the whole of his testimony, without any

reservation, and who were thus happily freed from those painful

struggles which others of a more highly intellectual and abstract

turn of mind so sorely felt. These features of Mr. MacPhail's mental

and Christian character rendered his ministry eminently successful

among his own flock, and all over the North, while his private

dealings with those under serious impressions were signally blessed

for removing their doubts and establishing their minds in the faith

of the gospel.

Mr. MacPhail's life

was not a long one, for his health soon began to decline. As long as

he had any strength remaining, however, he continued faithfully to

discharge the duties of his office. He died 23rd Jan., 1774, in the

58th year of his age.

Mr. Robert Arthur,

his successor, was inducted into the charge in 1774. He assumed at

first an evangelical strain of preaching, and associated with the

most highly-esteemed ministers, such as Mr. Calder of Urquhart, and

Mr. A. Fraser of Kirkhill. His knowledge of Gaelic, however, was

very imperfect, and this rendered his preaching in that language

utterly inadequate to convey the simplest truths to his Highland

hearers. Another circumstance led to an estrangement between him and

the pious among his people, and ultimately put an end to his

usefulness among them. Air. Gordon of Ardoch dying, and the family

becoming extinct, the estate was sold to a stranger of the name of

Munro, who, in honour of his wife, changed the name of the place and

called it Poyntzlield. He was succeeded by his nephews, first

George, and then Innes Gunn Munro, the latter a Colonel in the army.

The Munros of Poyntzfield have, in all their generations, been the

votaries of gaity and pleasure rather than of the more staid and

money-making pursuits of the world. Mr. Arthur, then a young,

unmarried man, became only too intimately acquainted in his new

heritor's family. This intimacy let to his marriage with the laird's

sister, and his consequent residence almost entirely at Poyntzfield,

to the utter neglect of the week-day duties of his office. This

course of action alienated from him the more serious among his

parishioners, while he himself became a bitter and implacable enemy

of all the Evangelical ministers with whom he came in contact. His

acquired fluency in after years in the Gaelic language, and a

certain knowledge of medicine, by which he made himself useful to

many, retained the majority of his parishioners as his hearers; but

all the seriously disposed regularly attended the ministrations of

the eminent Mr. Charles Calder of Ferintosh. Mr. Arthur was thrice

married. His eldest daughter, an excellent and amiable woman, was

the wife of the late Mr. Alexander Gunn, minister of Watten in

Caithness. When the close of his life approached, and he was

confined to bed, he was glad to receive supplies for his pulpit from

all the ministers who were willing to give them. Mr. Calder had long

before "gone into heaven," but his successor, Mr. MacDonald,

sometimes preached in the open air close to the manse, Mr. Arthur

sitting at the window and listening. He was a sound theologian, and

admired Mr. MacDonald as a preacher, but, alas, he gave no sign of

any change of heart. He was the same in the immediate prospect of

death as he had been through life. He died in 1821, in his 78th year

and the 47th of his ministry.

The day after my

settlement my wife was confined to bed. The pains of labour had set

in, and, alas, with more than ordinary symptoms of a fatal

termination. That night I had a few hours of hasty sleep. I awoke

from my troubled slumber, with a deep sinking of the heart, to the

realities which my dreams had been presenting to me. During the

course of her illness I was frequently at the side of her dying bed.

Our first alarm was excited by the peculiarity of her case; it was

that of difficult and protracted labour. Mrs. Smith of Cromarty, the

wife of my much-esteemed co-presbyter, being informed of the

affecting circumstances, volunteered her services in ministering to

our comfort and encouragement under the burden of anxious fears. My

poor Harriet was delivered of a dead child. And, alas, when the

pains of labour were over those of dissolution followed. Death came

in his wonted manner—slowly, irrevocably, without giving way.

Harriet uttered a few incoherent sentences, she fell into a swoon,

and breathed out heavily for a few moments her last sighs. It was

the 7th of May, 1822, at six o'clock of the evening.

The funeral was

numerously attended. I was so completely prostrated as to be quite

unable to accompany her beloved remains to their last resting-place.

My venerable and sympathising father, however, supplied my place as

chief mourner. Toe body was deposited in Cullicudden churchyard, a

beautifully sequestered spot, lying on the southern shore of the

Cromarty firth.

Mr. MacDonald of

Ferintosh often visited me, and preached to my people. Shortly after

the death of my beloved wife, he passed on his way to preach at

Cromarty, and I accompanied him on horseback. The ride thither and

back on the same day completely exhausted me, and I lay down on my

return wishing that I might die. Such a desire came upon me so

strongly that I hailed with delight every unsuccessful effort of

nature to regain its former position under the pressure of present

weakness, as so many sure precursors of death would unite me to her

from whom I had been so recently and sorely separated. I gradually

recovered, however, but still the notion haunted my mind. Then

conscience began to ask, "Why did I wish to die?" My sorrows at once

responded to the inquiry—"dust to be with Harriet." "But, was I sure

of that? If Harriet was in heaven, as I could not but hope that she

was, was nothing else to be the consequence of death to me but to go

to heaven merely to be with her?" I was struck dumb; I was

confounded with my own folly. So then, the only enjoyment I looked

for after death was, not to be with Christ, but to be with Harriet!

as if Harriet without Christ could make heaven a place of real

happiness to me! This discovery of my own miserable sources of

comfort threw me into a dreadful state of despondency. I was

perambulating the garden of the manse at the time; I left it, and

betook myself to my bedroom, and felt all my props suddenly

crumbling down under me. I was In a state of indescribable alarm. I

had a bitter feeling of insecurity and of discontent. I threw myself

on my knees to pray, but could not. My spirit was angry, proud, and

unsubdued, and all these unhallowed feelings took direction even

against God Himself. He it was who had deprived me of the object of

my warmest affections. Not only so, but Be had withdrawn from me the

only source of consolation out of which I could draw strength to

bear me up under so great a bereavement. Oh, what a God had I, then,

to deal with—how like Himself—how unlike me! "But who is a God like

unto Him, who pardoneth iniquity, and who passeth by the

transgressions of the remnant of His inheritance." I was somewhat

humbled, and I made another attempt to pray. But now felt that I was

entirely in His power. All my sins stood out before me. I attempted

to come to a settlement with God about them, on the terms of a

covenant of works. But I soon found that I was sadly out in my

reckoning; like a schoolboy, in a long and tedious arithmetical

question, who has come to an erroneous conclusion, and who has

blundered more in searching out the cause of his error than when at

first he erred, so it was with me. God brought to my remembrance the

sin of my nature, the sins of my youth, and the sins of my daily

omission and commission. I had no chance with him; He was too holy

and too just a God for me. I attempted to justify myself; I betook

me to the oft-repeated, but just as often foolish and unsuccessful,

plan of "washing myself with snow-water to make myself never so

clean." But the result was the same as in the case of Job, "He

plunged me into the ditch, so that my own clothes abhorred me." This

conclusion threw me into despair; I flung myself on the floor, not

to pray, for I deemed that, in existing circumstances, quite

needless, but just to wait like a condemned criminal for the coming

forth of an irrevocable sentence of condemnation. I felt that I

deserved it, and I felt equally hardened to abide the result. But,

"who is a God like unto Him " in dealing with transgressions? In my

then present state, and in the sovereignty of the Spirit's

influences, that passage came to me with much power, "I am the

door." It glided into my mind without any previous attempt to get at

it. But, like a light, dim at first, it gradually and rapidly

brightened. My bonds were forthwith unloosed, my darkness was

dispelled. Like the lepers in Israel of old I had only the

alternative of life or death in any case. But God was gracious. I

laid hold of the hope set before me. I thought, believed, and felt

that I had actually entered the " Door." I found it was wide enough

for a sinner, and high enough as a door set open by God and not man,

by which to enter. If I may dare to say it, I did enter that door,

even then, and at that solemn moment, notwithstanding the pressure

of my outward bereavement and of my inward conflicts; having

entered, I did experience "all joy and peace in believing." In the

world I had only "trouble," in Christ I had "peace;" and in that

peace I was enabled to resign, without a murmur, my beloved Harriet,

soul and body, to His holy care and keeping. I resumed prayer, and

felt much liberty, comfort, and enlargement. It was in the evening

of one of the days in the week immediately after her death. I had,

about an hour or two before then, gone from the garden to the

parlour, and risen from the table in an uncontrollable agony of

sorrow, rushed out at the door, and hurried up to my room. But after

the mental conflict above described, and the most gracious

deliverance afforded me, I returned to the parlour, to the society

of my beloved friends, in that peace of mind which Christ describes

as " peace in Him," in the very midst of those "troubles" which we

must, and shall "have in the world," but as the result of His

"victory" over it. My present tranquillity, compared with my former

"fight of afflictions," and so immediately succeeding it, astonished

my friends, and they could not but ask the reason why. I could only

say that, "the Lord had given, and the Lord had taken away, blessed

be the name of the Lord." For many days, and even weeks and months

afterwards I passed my time in prayer, in faith, and in sorrow as to

the things present, but rejoicing not a little in the God of my

salvation. Alas! this sunny season was succeeded afterwards by a

long dreary day of coldness, clouds, and darkness, but it has never

been forgotten, nor have its salutary effects been dissipated or

lost.

My revered father,

having been present at the death and burial of my beloved wife, soon

afterwards returned home. He went by Tarbat manse across the firth

to Golspie, and from thence he immediately proceeded to Kildonan.

As my mind became

more composed, and the soreness of my sorrows, by the healing hand

of time, was gradually wearing off, I engaged in the Sabbath and

week-day duties of my office. I commenced a course of ministerial

visits to the families of the parishioners. The whole parish I

divided into districts, each comprehending as many families as I

could conveniently visit during the course of a day. Intimation was

also given from the pulpit, and the whole was finished in a period

of ten months from the time 1 began until it was concluded. It was

true indeed that the time was prolonged farther than it would

otherwise have been, owing to various other duties interposing iii

the meantime. The line of work which I prescribed to myself was, to

visit each family separately, from which all not belonging to it

were excluded. With the heads of the family I held a confidential

conference alone, the children or servants not being present. 'These

were then called in, and, after asking each of them a question in

the Shorter Catechism, beginning with the heads of the family,

concluding with the servants, and addressing to all a few

admonitions, the visitorial duty terminated. I took up, at the same

time, a census of the whole population, one column being devoted to

the names of individuals, divided into families and numbered as

such; another, setting forth their designation and places of

residence; and a third, containing what might strictly be called the

moral and religious statistics of the parish, or remarks

illustrative of the state, character, and knowledge of each

individual. My kirk-officer, John Holm, accompanied me in all my

peregrinations through the parish on this occasion from first to

last.

luring my incumbency

in Aberdeen, one of my most esteemed acquaintances was Mr. Nathaniel

Morren, then a student of divinity. Soon after the death of the

venerable Kenneth Bayne of Greenock, I was, as already stated,

invited to preach as a candidate for that vacant charge. I was

succeeded by another, Mr. Angus 1lfacbean, some time before then

assistant preacher at Croy within the presbytery of Nairn. In the

choice of a minister which followed, Mr. Afacbean was chosen. But

there was a minority for myself, and these were so dissatisfied with

the choice of the majority that they resolved to withdraw and to

build a church for themselves. At the head of them was Duncan

Darroch, an eminently pious man of the old school, with whom

afterwards I became acquainted intimately. I was now minister of

Resdlis, and to ask me to become their minister was, in the

circumstances of the case, out of the question. But my

recommendation had weight, and I warmly recommended my friend Mr.

Morren, who, accordingly, became their minister. Soon after his

induction to his new charge at Greenock, he married Miss Mary Shand,

with whom, and her excellent mother and sisters residing at King's

Street, Aberdeen, I was most intimately acquainted. He and his wife,

some years afterwards, visited me on their way to Strathpeffer. He

then preached for me a most able sermon. But my recollection of that

is not so distinct as of a lecture at family worship on the Sabbath

evening, by which, in its soundness of doctrine, depth of thought,

and even of soul-exercise in the truth of God, I felt my soul

refreshed as it seldom had been before. Previous to the Disruption

of the Church of Scotland in 1843, Mr. Diorren's conduct was not

what had been expected of him. He was not content with joining the

Moderate party, to whom, from professed principle, he had been

conscientiously opposed, hut, besides, he became their champion in a

series of pamphlets at once the ablest and most malignant that were

written on the whole subject. Having fought in the battle, he at

once rose in the esteem and confidence of those with whom he had

identified himself. Lord Panmure presented him to the church and

living of Brechin, vacant by the resignation of Mr. MacCosh,

[Afterwards Dr. MacCosh, the eminent President of Princeton

Theological Seminary, New Jersey.—Ed.] whose successor he became. He

died there very suddenly.

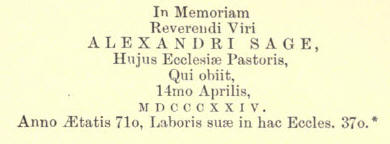

My father died at the

Manse of Kildonan, at half-past seven in the evening of the 14th day

of April, 1824. I had no sooner received the tidings of his death

than I immediately set out for Kildonan. The preparations for his

funeral occupied our time and consideration. To all those of the

most respectable classes, in a worldly point of view, funeral

letters were duly issued by a bearer sent for that purpose through

the immediate vicinity in the parishes of Loth and Clyne. The

length, depth, and breadth of the coffin, elegantly mounted,

exceeded anything of the kind I have ever seen. The procession,

after leaving the manse, proceeded in a westerly direction; and in

order to give each of his parishioners the opportunity of paying the

last tribute of respect to their beloved and venerable pastor, the

body was carried shoulder-high by six men, relieving each other at

intervals, all round the Dalmore, and by the banks of the river, to

the churchyard, and deposited in a tomb which he had erected soon

after my step-mother's death, and close beside her remains and my

mother's in their last resting-place. To their memories he had

erected a monument, with a suitable inscription; and, in remembrance

of him also, I inserted in the back of the wall of the church a

monumental slab bearing the following inscription:-

* It should be

recorded that Mr. Alexander Sage wrote an historical sketch of the

"Clan Gunn," which still exists in manuscript. As regards the merits

of this work, Mr. A. Gunn, minister of Watten, writes as

follows:—"Some years ago, when investigating the history of Clan

Gunn, I saw Mr. Sage's notes on the clan, and consider him to be the

chief authority on the genealogy and traditions of the Kildonan

branch, which included the family of the chieftains. As minister of

Kildonan he had the best means of knowing these, and his notes did

not go much beyond Kildonan.—Ed. |