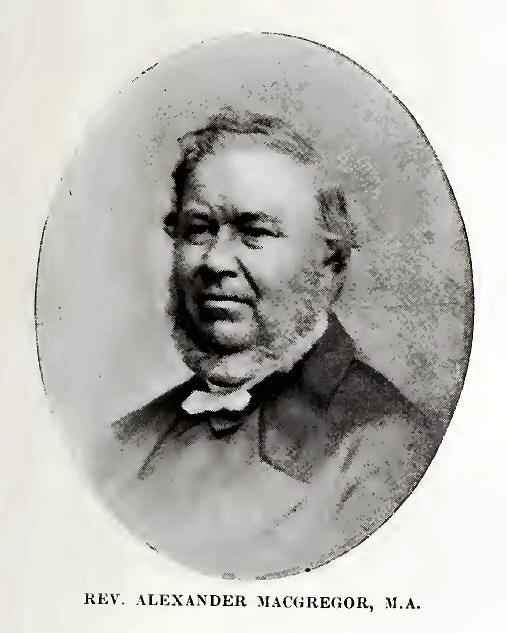

IN our last we intimated the death of the Rev. Alexander Macgregor, M.A.,

of the West Church, Inverness, on the 19th of October last, from a stroke

of paralysis. We then scarcely realised the great loss which Inverness and

the Highlands had suffered, and we have not done so in its full extent

even yet. It is, indeed, difficult to realise that we shall never again

see him in the flesh. He who for years scarcely failed to make his daily

call, until within the last twelve months, when he was perceptibly getting

more frail and we were a little further out of his way. Even then he would

pay a visit two or three times a-week, and have his interesting chat, his

quiet, enjoyable laugh, and his puff, for he heartily enjoyed the calumet

of peace, though he never carried pipe nor tobacco. His fund of anecdote,

Highland story and tradition, was inexhaustible; and the various incidents

in his own life-experience, which he enjoyed to recapitulate in his

characteristically modest and charming style to his more intimate friends,

were delightful and most instructive to listen to.

He was for ever doing good. The number of letters, petitions, and

recommendations which he has written for the poor is scarcely credible.

No one asked for such favours in vain from him. He was the means of

starting many a young man in a successful career, especially young men

from the Isle of Skye, among whom maybe mentioned Mr Rowland Hill

Macdonald, of the Glasgow Post-Office, and Mr Matheson, Collector of

Customs at Perth. He often related the particulars of their humble

beginnings; how he was instrumental in securing their first civil

appointments, and how interested he continued to feel in their success

in life; and, were this the place, the story would well bear the telling

much to his and their honour. Among other acts of goodness he succeeded

in securing pensions, of £ioo each, for the late Misses Maccaskill, and

for years before their death he personally drew the money for them.

In his ministerial sphere his labours were incessant. He was always in a

hurry, visiting the dying, the poor, or the distressed in spirit; going

to a marriage, a baptism, or a funeral. And it made not the slightest

difference to what faith they belonged.

The sympathies of his large heart extended to every denomination,

Catholic, Episcopalian, or Dissenter; while, at the same time, he stood

firmly by his own beloved Kirk, and fully believed in her as the Church

of Scotland. Though his own congregation in recent years largely

increased—more than double during the last fifteen—he was as often

consoling the last moments of the dying of other denominations as those

of his own flock. He was ever in request at the supreme moment to sooth

and encourage. He left those of his cloth who had been cast in a more

contracted ecclesiastical mould to thunder out the law. His favourite

theme was the Saviour and His Gospel of love and peace to men. He was

constantly smoothing away any difficulties occurring between his

friends, and he almost invariably succeeded in bringing them again

together. Some of his most intimate personal favourites were adherents

of other denominations; and you were as sure to meet him at the funeral

of a Roman Catholic as at that of a Presbyterian. His large heart, his

truly catholic spirit, his boundless charity knew not the mean, selfish,

repulsive creed of those that would scarcely admit to Heaven any one but

those who could see eye to eye with them in mere matters of

ecclesiastical form and ceremony. When a boy we would run a mile off the

road to escape meeting the minister. Children almost adored Mr

Macgregor. They would run after him, meet, and cling to him. He loved

them; they instinctively knew it; and they loved him in return; and

there are no better judges of the man who deserves to be loved than they

are. He endeared himself, in short, to all who knew him—old and young.

We must, however, now deal more with his career as a

minister and a man who left his mark, deeply impressed, especially on

the literature of the Highlands. And we cannot more appropriately

introduce the subject than by quoting a letter from the Rev. Robert

Neil, minister of Glengairn, a gentleman who occasionally corresponded

with our revered friend in his latter years. Mr Neil writes under date

of 28th October:-

I was truly sorry to hear of the death of your much

esteemed contributor, the Rev. A. Macgregor, an event which has called

up many tender recollections in this, his native glen. As there will, no

doubt, be a lengthened notice of him in an early number of the CeItic

Magazine, I beg to communicate certain facts in his family history in

correction of several mistaken statements made in the newspaper notices

of his death. His father, the Rev. Robert Macgregor, came from

Perthshire in the end of the last century to be Missionary on the Royal

Bounty at Glengairn, and continued there until 29th December 1822, when

he left to be minister of Kilmuir, in the Isle of Skye. During his

residence in Glengairn he became exceedingly popular both as a preacher

and as a member of society, and his memory is still fondly cherished by

not a few of the older inhabitants who have a vivid recollection of his

pulpit ministrations, and of the kindly way in which he mingled with

them in their joys and in their sorrows.

His lately deceased son was born in the Mission House

in 1808, I believe, and he is also well remembered by several of his

surviving school-fellows, by whom he was much beloved.

Besides preaching in Gaelic and English, his father

taught a school through the week, and, as he was possessed of no mean

scholarly attainments, he was enabled to impart to his son in early life

that sound education which in after days bore such ample fruits. His

excellent management in financial affairs is likewise worthy of record.

Although his stipend here never exceeded sixty pounds, yet on that small

sum he brought up a large family, and saved what was considered at the

time of his leaving for Skye no trifling amount.

Young Macgregor entered the University of Aberdeen

when a mere boy, and matriculated at King's College at the early age of

twelve, two years before his father removed to Skye. Here he made the

acquaintance of the famous Celtic scholar, Ewen Maclachlan, then Rector

of the Grammar School, and the leading spirit in the Aberdeen Highland

Association of his day. Mr Macgregor delighted to relate the

circumstances connected with his first interview with his distinguished

brother Celt, and tell how, under Maclachlan's influence, was fanned the

natural love which even then existed in his own youthful bosom for the

language, literature, and antiquities of the Highlanders. He regularly

attended the University, graduating in due course, after having carried

away several valuable prizes for distinction in natural philosophy and

mathematics. Having gone through the usual course in the Divinity Hall,

he returned to Skye, was duly licensed as assistant to his father, and

soon became a very popular preacher. In one day he received

presentations to no less than three charges, one of which was to

Applecross, and another to the Parish of Kilmuir, as colleague and

successor to his father, which he accepted, and to which he was ordained

in 1844. Here he continued for several years, imbibing the fountain of

his affection in after years for his beloved "Isle of Mist" and its

people, and gathering the vast stores of traditionary Gaelic legend and

lore, with which he afterwards, in these pages and elsewhere, delighted

so many thousands of his countrymen. He continued in Kilmuir until his

father's death; but soon afterwards received a call to the Gaelic

Church, Edinburgh, which he accepted. He then removed, with some

reluctance, from his beloved Isle to minister to his Gaelic countrymen

in the Scottish metropolis.

In 1853, on the death of the Rev.

Alexander Clarke, he was presented to the West Church, Inverness, where

he ceaselessly ministered to a devoted and steadily increasing

congregation until a week before his death. He was the most loveable

man, and the best beloved in the Highland Capital. As the Courier

prettily and accurately puts it—

His quiet and pleasant manner, and the kindly

interest which he took in the concerns of his parishioners were not

assumed for the occasion, but were natural and habitual traits of his

character. It mattered nothing to him whether the persons who solicited

his services belonged to his own congregation or not. He was incapable

of refusing to do a kindly office, and he never dreamt of sparing

himself trouble, He never acted as if conferring a favour: There was no

formality in his nature. He chatted away with a frankness and simplicity

that won universal confidence, and by their transparency kept guile at a

distance.

Mr Macgregor, though one of the most eloquent and

best Gaelic speakers of his time, curiously enough, did not, for many

years, preach in his native language; but though he did not use it in

the pulpit, he did so constantly in his ceaseless visitations of the

Gaelic portion of his own flock and the general body of the Gaelic

population of the town and district, and found it a sure and ready means

to reach and touch their warm Highland hearts.

Though he will be sorely missed in the Highland

Capital as a man, a minister, and as a Christian of wide catholic

sympathies and true charity, throughout the Highlands and the country

generally, he will be specially missed as a genuine type of the fine old

Highlander, as our best Gaelic scholar, and the first authority upon all

questions connected with the history, antiquities, traditions, language,

and literature of his countrymen; and he was ever ready to give the

benefit of his extensive knowledge to others. He has written what would

form several volumes since he first commenced, in the parish of Kilmuir,

to issue among his neighbours, his manuscript magazine, the "Kilmuir

Conservative Gazette," written entirely in his own beautiful hand. He

afterwards contributed to almost every periodical or newspaper that

interested itself in any phase of Highland life and though:. lie

coiiributed largly to "Cuairtear nan Gicanu," edited by Old Norman

Macleod. Most of his contributions are signed "Sgiathanaci," or

"Alasdair Ruadh," but many are only signed "S.," and, in several cases,

not at all. On one occasion, during the absence of the editor, he wrote

the whole number, and, he repeatedly wrote the greater portion of the

monthly issue. He was afterwards a regular contributor to "Fear Tathaich

nam Beann," conducted by the Rev. Dr Clerk, of Kilmallie. In his latter

years he contributed largely to the Gael, published by Angus Nicholson,

first in Glasgow and latterly in Edinburgh. To this periodical he

contributed in all not less than some 270 closely printed pages of the

purest, idiomatic Gaelic, between 1372 and 1877, while during the same

period he wrote extensively for the Highlander and the Celtic Magazine.

It will be remembered that his name appeared on the

title- page of our first volume as joint Editor, a fact which, no doubt,

greatly helped to secure for the magazine its early popularity among

educated Highlanders. His contributions are still fresh in the memory of

the reader, but we may recal a few of the most important, such as

"Destitution in the Highlands;" "Highland Superstition," afterwards

considerably extended, and published as an Appendix of 64 pages to the

Second Edition of "The Prophecies of the Brahan Seer;" and the "Life and

Adventures of Flora Macdonald," now passing through the press in volume

form. In addition to these he wrote over twenty articles on other

subjects connected with the Highlands, making altogether more than 230

closely printed pages of this magazine.

His "Parish of Kilinuir," Published in the "New

Statistical Account" in 1842, extends to 50 pages, and is one of the

most valuable contributions to that work. What he had written for that

publication would have made about 20 pages additional, but the Editor

found it necessary to limit the various writers to a much smaller space

than Mr Macgregor was actually allowed. We have perused the original

MS., and can safely assert that some of the most interesting portions to

Highlanders are left out. These have, however, found their way into

print in our own pages and elsewhere in connection with other subjects.

He translated the Apocrypha into Gaelic several years ago, at the

request of Prince Lucien Bonaparte, who paid him a visit in Inverness,

and afterwards published Mr Macgregor's beautiful translation in a

handsome volume. The MS., apart from its high literary merit, was itself

a work of art. Several of his most valuable contributions to Gaelic

Literature were delivered at meetings of the Gaelic Society of

Inverness, all of which are preserved in their Annual Volume of

Transactions. Among these will be found a Gaelic Lecture of great value,

delivered on the 24th of October 1873, on the Highlanders, their

Language, Poetry, Music, Dress, and Arms. His knowledge of Highland

music was equal to his other Celtic acquirements. He was an excellent

performer on the great Highland bagpipes and on the violin, and he was

almost invariably, for many years, one of the judges of Highland music

at the Northern Meeting. He was a popular lecturer, and delivered

several in Inverness, always to large and appreciative audiences, on

Highland subjects.

He was scarcely ever in bed after five o'clock in the

morning, which accounts for the great amount of work he was able to

perform in addition to his ministerial and parochial duties. Before

breakfast he had already done a fair day's work with his pen, and,

unlike most ministers, he prepared and wrote his sermons on the Mondays

and Tuesdays. He had thus the rest of the week at his disposal for his

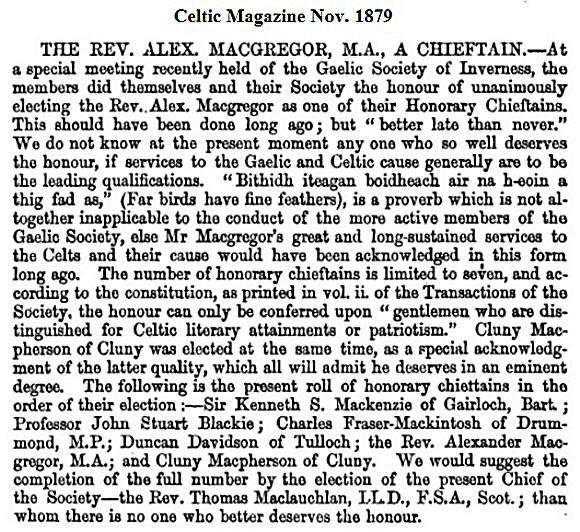

other duties. He was Honorary Chieftain and Life Member of the Gaelic

Society of Inverness, and on one occasion presided at one of its Annual

Assemblies It was probably very much owing to his great modesty and

retiring disposition, and perhaps in consequence of the neglect of his

friends that his Alma Mater did not confer upon him some Degree of

recognition in his latter days, a fact often referred to with regret in

literary circles for the last few years.

About six weeks before his death he paid a visit to

his son Duncan, a Medical Doctor in Yorkshire, who took advantage of his

father's visit to take him to London, where he greatly enjoyed the

wonders of the Metropolis. His experiences there, and the impressions

made upon him, he humorously described in a Gaelic letter to the writer,

which appeared in our October number.

No one was ever more universally and sincerely

mourned, not only in Inverness but throughout the Highlands, and even

among his countrymen abroad, as we have a good opportunity of knowing.

Scarcely a letter reaches us but contains warm expressions of regret for

his loss.

The Rev. P. Hately Waddell, LL.D., who enjoyed an evening

with him here a few years ago, writes, among hundreds of others :-

It

gave me great grief to see that you lost so dear a friend and so

valuable a contributor. The announcement of his death in the papers was

a sad surprise to myself, for I was not aware that he was complaining,

and it was by your own reference to them in the magazine that I

understood at all about the circumstances attending it. The slight

opportunity I had of his personal acquaintance at Inverness was enough

to satisfy me that he was a most estimable man, and I am quite sure that

his loss will be very deeply felt by the whole community.

The Secretary of the Gaelic Society received the

following letters, among several others, expressing regret.

Sir Kenneth Mackenzie of Gairloch wrote—

I am glad the Gaelic Society is to attend the funeral

of our friend Mr Macgregor. I certainly should have joined in the

tribute of respect that will be paid to his remains had I been able to

do so. Indeed, for him it will, I think, be something more than a

tribute of respect; it will be one of affection. Others will succeed

him, but no one will ever replace him, and I can hardly explain to

myself how much I feel the loss of one who was to me a kindly, pleasant

acquaintance.

The Rev. Mr Bisset, R.C., Stratherrick, wrote—

For Mr Macgregor I have always entertained, since

first I knew him, feelings of the deepest respect. As an unworthy member

of the Gaelic Society, I would have considered it a melancholy duty to

attend the funeral of this most worthy man—a father and pillar of the

Society, and a most genuine Celt.

Colonel Cluny Macpherson of Cluny, C.B., wrote—

I was very sorry to hear of the death of the Rev.

Alex. Macgregor, for whom I have had a very great regard, and I regret

extremely being unable to be present at his funeral, and to pay the last

mark of respect to the memory of one so much beloved.

The funeral, which was a public one, was one of the

largest ever seen in Inverness. The people began to gather at 4 Victoria

Terrace, the residence of the deceased, at noon, though the cortege was

timed to start at i P.M. The Chronicle, for which Mr Macgregor also

wrote several Gaelic contributions, accurately describes the scene:—

Among the first to arrive were the members of the

Presbytery of Inverness. Religious services were conducted in the house

by the venerable Dr Macdonald. Meanwhile the muster outside grew larger

and larger. All classes were represented. Landowners, magistrates,

clergymen of all denominations, merchants, farmers, and humble workmen

assembled with the one desire to pay a last tribute to a man who had so

well represented broad charity and universal brotherhood. Dr Mackay aud

the Primus, as well as Dr Macdonald, were there with their weight of

years. The Rev. Mr Dawson, the Catholic priest, was there also, and so

were Free and Established Church ministers from a distance. The Masons

of St Mary's Lodge, of which the deceased was chaplain, turned out to

the number of 120; and so, to the number of zoo, did the Gaelic Society,

headed by Mr Fraser-Mackintosh, M.P., one of their honorary chieftains.

Mr Mackintosh of Raigmore was also present.

Shortly after one o'clock the procession started in

the following order The Town Officers.

The Provost, Magistrates, and Town Council.

The

Lodge of St Mary's Freemasons.

The Lodge of St John's Freemasons (No.

6 of Scotland).

The hearse.

The chief mourners and immediate

friends.

The Presbytery of Inverness.

The Kirk-Session of the West

Church.

The Members of the Gaelic Society.

The public.

In this order the long procession moved slowly by

Millburn Road, Petty Street, High Street, and Church Street to

Chapel-yard, where the interment took place in the presence of

thousands. The pall-bearers were:

Mr Robert Macgregor, Edinburgh, and Dr D. A.

Macgregor, Clayton West, Huddersfield—sons.

Mr James Menzies,

Melrose, and Mr Duncan Macgregor, Inverness—cousins.

The Rev. Dr

Macdonald, High Church, Inverness.

The Rev. J. Macnaughton, Dores.

Colonel J. P. Stuart, Inverness.

Mr A. A. Gregory, Inverness.

Along the route spectators lined the sides of the

streets. The town bells and those of the High and West Churches were

tolled. Shops, banks, and places of business were closed. In short,

business was universally suspended, and it might be said that almost all

the population was in the streets. Nothing could be simpler and nothing

more impressive than the manner in which Inverness paid its last tribute

to the man who had so long gone in and out among its people,

unostentatiously doing good, and making friends of all and enemies of

none.

Inverness shall certainly never see his like again,

and for ourselves, we can only repeat what we said in our last issue:—In

him the Celtic Magazine has lost its first and best friend; while the

Editor personally has lost the society of one whose most intimate and

personal friendship he valued above all others, and whose life and walk

he admired as the most complete model of true Christian charity and

gentleness it has ever been his lot to know.

His loss to his own family and more immediate friends

is not for us to measure; but their cloud of sorrow has a silver lining,

which ought to qualify their bereavement, in the universal regret and

sympathy of a whole people. A. M.

THE CELTIC MAGAZINE

November 1879 THE AGED PIPER AND HIS BAGPIPE

There are many incidents of deep interest connected with the attempt to

reinstate the Stuarts on the British throne. Since the period of the

Rebellion, many things have occurred, and not a few changes have happily

tended to strengthen the reigning dynasty, and to extinguish the

Stuarts' last ray of hope. The Stuart family, as is well known, had many

friendly and faithful adherents in the Highlands of Scotland, by whom

every attempt was made at the time to obtain the services and to secure

the allegiance of the powerful and brave. The subject of this brief

notice was a man far-famed in his day, for his proficiency in the

martial music of the Highlands, and not less so for his personal agility

and warlike spirit John Macgregor, one of the celebrated “Clann

Sgdulaich,” a native of Fortingall, a parish in the Highlands of

Perthshire, was, like too many of his countrymen, warmly attached to the

Prince’s cause. He embraced, in consequence, the earliest opportunity of

joining his standard. Soon after Charles had set his foot on the soil of

Scotland, Macgregor resorted without delay to the general rendezvous of

the clans at Glenfinnan, and shortly became a great favourite with the

Prince. Macgregor was a powerful man, handsome, active, well-built, and

about six feet in height. Ho was a close attendant upon his Royal

Highness—accompanied him in all his movements, and was ever ready and

willing to serve him in every emergency. Charles placed great confidence

in his valiant piper, and was in the habit of ad dressing him in kind

and familiar terms. Unfortunately, however, the gallant piper bad but a

very scanty knowledge of the English language, and could not communicate

to his Royal Highness various tidings that might be of service to be

known. The Prince, however, acquired as much of the Celtic tongue, in a

comparatively short time, as enabled him to say, "Seid suaa do phiob,

Iain” (Blow up your pipe, John). This was a frequent and favourite

command of the Prince. When he entered into the city of Edinburgh, and

likewise after the luckless Cope and his dragoons took flight at

Prestonpans, the Prince loudly called, “Seid soas do phiob, Iain.” John

could well do so, and the shrill notes of his powerful instrument were

hoard from afar. He stood by the Prince in all his movements, and went

wherever he went. He joined in the march to Derby; was present at the

battle of Falkirk; played at the siege of Stirling Castle; and appeared

with sword and pipe at the irretrievable defeat at Culloden, where,

alas! on the evening of the fatal day, he beheld tho last sight of his

beloved Prince.

Poor John received rather a severe wound by a ball in the left thigh,

causing a considerable loss of blood, and consequent weakness. By the

aid of a surgeon which ho fortunately met with, the wound was dressed,

and he made the best of his way, after many hair breadth escapes and

distressing deprivations, to his native glen, where he resided to the

day of his death. He had numerous descendants—four sons and eight

grandsons —and all of them pipers. Of these, the last alive, but now

dead, was a grandson, the aged piper referred to at the head of this

article, who was also a John Macgregor.

The identical bagpipe with which Macgregor cheered the spirits of his

Jacobite countrymen in their battles and skirmishes was still in the

possession of this grandson, the John Macgregor already alluded to, who

departed this life only a few years ago, at a very advanced age, at

Druimcharry, in the parish of FortingalL The instrument was in excellent

preservation, and was undoubtedly worthy of a place in some museum. It

had but two drones, the third in such instruments being but a modem

appendage Its chanter was covered with silver plates, bearing

inscriptions in English and Gaelic. The late Sir John Athole Macgregor,

Bart,, added one plate to it, on which are inscribed the following words

in both languages:—“These pipes, belonging to John Macgregor, piper to

his Grace the Duke of Athole, were played by his grandfather, John

Macgregor, in the battles of Prince Charles Stuart’s army in 1745-6, and

this inscription was placed on them by his Chief, Sir John Athole

Macgregor, Bart, of Macgregor, in 1846, to commemorate their honourable

services.”

The late owner, John Macgregor, was also a celebrated piper in his day,

and was able to play the old pipe with wonderful efficiency, until he

parted with it, as described below. Ho gained the prize pipe at the

Edinburgh competition for Piobaireachd in July 1811. Ho was for several

years in his youth piper to his Grace the Duke of Athole, and

subsequently to Mr Farquhanson of Monaltrie, and Mr Farquhareon of

Finzean, In 1813 ho played at the assembling of the Isle of Man

proprietors at Tynwald HilL He performed at tho head of his clan in

Edinburgh during tho Royal visit in 1822. He played the Piobairoachd,

“ThMn* na Griogairich, Thin* na Griogairich, tb&inig, thkinig, thMn’ na

Griogairich,” in the great procession, when his Chief, Sir Evan

Macgregor, Bart, of Macgregor, was conveying the Regalia of Scotland

from the Castlo to the Palace of HolyroocL He was piper to the Athole

Highlanders at the Eglington Tournament in 1839, and bad the honour of

performing before Her Majesty the Quoon at Taymouth Castle. But John

became latterly frail and aged, and was unfortunately in rather

straitened circumstances. Ho was modest and unassuming, and would rather

endure privations than let his wants be made known to others.

Worthy old John about sixteen years ago communicated by letter with his

namesake, the writer, and gave in detail the above particulars relative

to his grandfather and his ancient bagpipe. It was recommended to John,

for his own benefit, as well as for the preservation of the interesting

relic of the olden times in his possession, to give his consent to a

notice being inserted in the public prints, that he was willing to part

with it to some benovolent antiquary. The consent was given and the

notice duly made public. In a very short space of time John received

letters from several parties of distinction, among whom was Mr Mackenzie

of Seaforth, and other Highland proprietors, offering handsome sums for

the valuable relic. At length tho advertisement was observed by his

Grace the Duke of Athole, who lost no time in acquainting the aged

Macgregor that ho had every desire to become the owner of the

interesting instrument, and that ho behoved to have it, as John was

willing to part with it His Grace at the same time intimated to the old

man that ho would allow him not' only a sum equal to the highest offered

to him by any other, but would in addition settle upon him a comfortable

half-yearly pension as long as he lived. It is needless to say that the

Culloden bagpipe became at once the property of his Grace, and that, no

doubt, it now lies in silence in the ducal repositories of Athole, while

old John Macgregor has been for some years in the silence of the grave.

ALEX. MACGREGOR.

The Life of Flora MacDonald

Genealogy