|

James Chalmers: Missionary to Cannibals

by Christa G. Habegge

His fearlessness won the respect of the

cannibals;

his compassion, their loyalty and friendship

The

Chalmers who invested his life as a missionary to New Guinea was very

different from the carefree, high-spirited youth who grew up in county

Argyllshire, Scotland. The one trait that bound the man to the boy was a

love of adventure. Chalmers wrote of his youth: "I was very restless and

dearly loved adventure, and a dangerous position was exhilarating." The

Chalmers who invested his life as a missionary to New Guinea was very

different from the carefree, high-spirited youth who grew up in county

Argyllshire, Scotland. The one trait that bound the man to the boy was a

love of adventure. Chalmers wrote of his youth: "I was very restless and

dearly loved adventure, and a dangerous position was exhilarating."

James Chalmers was born in

1841 in the town of Ardishaig. His father, a stonemason, and his

Highlander mother brought him up with the stern discipline of a Scots

peasant home. His most vivid boyhood memories centered around the nearby

Loch Fyne and other bodies of water in the county. Young James became a

favorite of the local fishermen. He won recognition for his bravery in sea

escapades, having rescued comrades from drowning on several occasions.

As a scholar, James did not

distinguish himself, "either in attendance or conduct," but he was a

leader among his classmates, particularly when there were fights between

rival schools. At 13, James left the local school and attended an upper

level grammar school. During his early teens, James was busy "sowing wild

oats," but it was also during this time that he made a decision which

affected the whole course of his life.

Despite his rebelliousness,

James attended a Sunday school class under the direction of the Reverend

Gilbert Meikle, a godly man who wielded a strong influence over him.

During one class Mr. Meikle read to the children a letter from a

missionary to the cannibals in the Fiji Islands. When he had finished

reading, he looked around the room and said, "I wonder if there is a boy

here this afternoon who will become a missionary, and by and by bring the

Gospel to cannibals like these?"

Moved, Chalmers immediately

responded in his heart, "Yes, God helping me, I will."

The memory of the incident

diminished during the next few years. James, as yet unconverted, strayed

from the influence of the Sunday school. However, in November 1859, two

preachers from Northern Ireland arrived to hold special meetings. A friend

prevailed on James to attend. At the service, James felt that the message

was intended for him. The following Sunday, James recorded that "in the

Free Church I was pierced through and through from the conviction of sin,

and felt lost beyond all hope of salvation. On the Monday Mr. Meikle came

to my help, and led me kindly to promises and to light ... I felt that God

was speaking to me in His Word, and I believed unto salvation."

Eighteen-year-old Chalmers

began immediately to testify of his conversion at meetings in his town and

county. Furthermore, he recalled his boyhood vow to become a missionary

and renewed it, this time confident of the Lord's leadership. On the

advice of a missionary home on furlough, James applied to the London

Missionary Society, and was accepted and sent by them to Cheshunt College

for theological training. His eagerness to go to the mission field

prompted him to study hard. Yet, he retained his love of adventure and

fun. He remained a leader in student activities and good-natured pranks,

one of which was donning a huge bear skin and terrifying the student body

during an evening meal.

Fellow students with

Chalmers at Cheshunt said of his appearance and influence: "He was tall

and thin ... His hair was black, and his eyes hazel with an endless

sparkle in them. He was active and muscular, lithe but strong ... By all

his natural qualities of body, mind and spirit he was a born pioneer and

leader of men."

During his student days,

James became engaged to a girl named Jane Hercus. They were married in

October 1865. Two days after his marriage, James was ordained to the

ministry. His appointment to Rarotonga, an island in the Hervey or Cook

group in the South Pacific, was cemented, and the couple looked forward to

January when they would sail for their mission field.

Fifteen months later, the

Chalmerses were still far from Rarotonga. They first sailed to Australia,

where they spent much time for repairs to the ship. From there they

secured passage to one of the Samoan islands from which they hoped to sail

on to Rarotonga. After waiting six weeks, Chalmers finally secured passage

aboard the Rona, commanded by a notorious pirate, Bully Hayes.

Unlikely as their

association must have appeared, the two men were instantly drawn to each

other. Probably, the "blustering pirate and the high-spirited missionary

... had nothing more in common than a reckless indifference to danger and

a thirst for adventure."

Chalmers continued to have

services on board ship as was his custom, and Hayes for his part tried to

behave as a gentleman and even required his men to attend.

On May 20, 1867, the

Chalmerses saw the mountains of Rarotonga. A boat could not get close

enough to shore, so a brawny native waded out to carry Chalmers to land.

The native wished to know his passenger's name that he might announce it

to those waiting on the shore. "Chalmers," the missionary said. "Tamate,"

was the nearest equivalent the confused native could call out to other

Rarotongans, and Tamate became Chalmers's name for the next 35

years.

Chalmers, eager to pioneer

a work for Christ, was disappointed to find the "gem of the Pacific," as

the beautiful island was appropriately called, already Christianized. For

the next ten years, he was responsible for the smooth operation of an

already-established mission. However, he set out to explore the island in

order to know his "parish" better, and his treks revealed that there were

still areas left unconquered. Life was easy on the island, and the

natives' only employment seemed to be fighting among themselves or

indulging in drunken festivals involving gross immorality. He determined

to find useful outlets for native energy. He reorganized an existing

Training Institution and also set about educating native children.

An important aspect of

Chalmers's missionary method became apparent in his work on Rarotonga: he

encouraged self-government and independence of European influence once a

native work was well established. He wrote: "So long as the native

churches have foreign pastors, so long will they remain weak and

dependent." He visited native churches on a regular basis and reported

that the "out-stations under the charge of native pastors contrast very

favourably with the stations under the care of European missionaries."

Chalmers had pleaded

repeatedly with the LMS to be assigned to a new field. In 1877 he finally

received instructions to move on to New Guinea. "Several bands of native

teachers from the islands went to New Guinea during that period, but only

a few survived the ferocity of the cannibals and the trying climactic

conditions." Like all challenges, this new one stimulated him.

New Guinea, or Papua, the

largest island in the world, located across from the northern tip of

Australia, was largely unexplored at the time of Chalmers's arrival.

Chalmers became to New Guinea what David Livingstone was to Africa. He

found the people "a very fine race physically, but living in the wildest

barbarism. Nose-sticks, huge rings adorning the lobe of the ear, necklaces

of human bones, gaudy-coloured feathers, repulsive tattoo marks, and daubs

of paint were almost the sole clothing of the men. The only additional

adornment of the women was their bushy grass skirts." The natives of New

Guinea, like those of Rarotonga, spent much of their energy fighting.

Tribal disputes were settled by bloodshed, and victorious tribes

celebrated with cannibal feasts. Many Papuan houses were built in the tops

of tall trees to help protect the inhabitants from surprise attacks.

Unlike the Rarotongans, however, the Papuans were industrious in the

cultivation of the soil. There were talented craftsmen among them in

woodwork or pottery. Surprising to the first missionaries, too, was the

fact that Papuan family life was much better developed than among many

primitive cultures. Parents were affectionate with their children, and

children, in turn, cared for sick or aging parents. Women enjoyed a much

better status -- approaching equality with men--than did the women of most

areas where Christianity had never permeated.

The Chalmerses, along with

a small staff of native teachers, established Suau as their first mission

center. Upon arrival, Chalmers handed out presents -- beads, leather

belts, red cloth -- to the suspicious natives to convince them that they

were coming peaceably. The village chief offered the Chalmerses the

hospitality of his hut while the mission house was under construction.

Privacy there was minimal, and household decorations consisted of human

skulls and other bones, and bloodstained weapons.

Nonetheless, Mrs. Chalmers

was delighted with the warm reception the missionaries received. "Tamate"

was more realistic, but said nothing to dampen her optimism. One day their

true peril became obvious. While Tamate was on his way to the shore, a

group of armed, yelling savages surrounded the partly built mission house.

Tamate rushed back and was confronted by a native warrior brandishing a

stone club. The missionary looked at him coolly and demanded the reason

for the attack. The savage responded that the villagers wanted "tomahawks,

knives, iron, beads," and that if these were not supplied, the

missionaries would be killed. Tamate replied calmly that he didn't give

presents to armed people. Again the savage repeated his demand and threat,

and again Tamate refused, over the frightened protest of a native teacher.

The natives eventually retreated to the bush for a parley, and the

missionaries spent a watchful, uneasy night. The next morning, a native,

without war paint, approached Tamate and apologized. Tamate received him

cordially." 'Now you are unarmed and clean,' he said genially, 'we are

glad to make friends with you,' and taking [him] to the house he gave him

a present." Tamate, by his refusal to be cowed by threats, won the respect

of the natives and eventually their loyalty and friendship.

Both Chalmerses worked

tirelessly to make the mission a spiritual success, he by conducting

services and she by teaching. Those who accepted Christ were carefully

nurtured in the faith. Tamate baptized only those who demonstrated a

genuine transformation and a growing knowledge of the Word of God.

Convinced that the work at

Suau was progressing well, Tamate was eager to penetrate other areas with

the gospel. In 1878, he travelled for several weeks, leaving his wife

alone among the natives. On his return he wrote: "Mrs. Chalmers says it is

well she remained, as the natives saw we had confidence in them, and the

day following our departure they were saying amongst themselves, 'They

trust us; we must treat them kindly. They cannot mean us harm, or Tamate

would not have left his wife behind.'"

In February 1879, Tamate

lost his beloved wife and brave helpmate. Her health had been broken by

repeated attacks of fever and the strain of the difficult mission work.

Tamate, though grieving, plunged into his work even more energetically.

Besides introducing Papua

to the gospel, Tamate accomplished the seemingly impossible goal of

promoting peace among the tribes all along the coast. According to those

who accompanied him on his visits to native villages, Tamate had a

remarkable influence over people. A fellow missionary wrote:

"Tamate's power over

savages was partly a personal thing ... It was in his presence, his

carriage, his eye, his voice. It was not only wild men whom he fascinated.

There was something almost hypnotic about him ... Then again, his

judgment, largely the result of wide experience in critical situations,

was unerring. He saw evil brooding where an inexperienced eye would have

seen nothing to fear; he was equally certain everything was satisfactory,

when a novice would have suspected danger.

"His fearlessness must have

been a great factor of success in his hazardous work. He disarmed men by

boldly going amongst them unarmed ..."

"Tamate was not only

fearless, but as a pioneer he was also perfectly cool ... His perfect

composure, as well as his judgment and tact, and fearlessness ... must

have brought him through a hundred difficulties ... during his long

service for Christ in New Guinea."

The natives themselves

testified most eloquently of his influence. When asked what prompted one

tribe to give up cannibalism, an old chief said simply, "Tamate said, 'You

must give up man-eating': and we did."

During a typical first-time

encounter with a savage tribe, Tamate and a native escort would wait on

board their boat until the natives on the shore had had a chance to notice

the strange vessel and absorb the shock of seeing a white man for the

first time. Usually, an armed party of men would climb into canoes and

approach the missionary boat. Tamate would then make signs of peace,

distribute presents, and make a brief address, stating that he had come to

make friends and planned to return for a longer visit in order to tell

them of a great Being of whom they were ignorant. He felt that the first

visit should be short -- just long enough to establish amiable relations.

Sometimes during such a visit, the natives would invite him ashore in

order that the rest of the village might admire his white skin. If the

reception were especially warm, he would be accorded the sign of affection

-- nose-rubbing. "Alas, " he wrote. "I cannot say I like this

nose-rubbing; and having no looking-glass, I cannot tell the state of my

face ... Kissing with white folks ... is insipid -- but this! When your

nose is flattened, ... and your face one mass of pigment [from the war

paint]!" After a successful first visit, he was assured that his longer

missionary campaign there would be well received.

In November 1884 Great

Britain announced that New Guinea was formally annexed as a territory.

Tamate was enormously successful in smoothing over native resistance to

the Protectorate. On his own initiative he visited tribal chiefs,

explaining the terms of the annexation. The chiefs were then invited

aboard a British man-o'-war for the official ceremony. Tamate was present

to explain the proceedings to the natives. After the ceremony, Tamate

corresponded often with British officials to ensure that the terms of the

agreement were kept and that the natives were treated fairly.

In 1888 Tamate married a

widow, "Lizzie" Harrison, a longtime friend of the first Mrs. Chalmers,

with whom Tamate had maintained correspondence. This second Mrs. Chalmers

provided the companionship and support Tamate had longed for since his

first wife's death. She too, proved herself to be a brave and self-denying

missionary. Unfortunately, like her predecessor, Lizzie Chalmers did not

live long in New Guinea. In 1900, after 12 years on the field, she died.

The last brief phase of

Tamate's service to New Guinea was spent visiting existing mission

stations. He was much encouraged by the arrival of a dedicated young

helper, Oliver Tomkins. Together they planned an expedition to the Aird

River Delta. The natives in that region were reputed to be fierce and

unapproachable, even by Papuan standards. No white man had ever seen them.

For a long time, Tamate had desired to make the dangerous trip there in

order to win them for Christ. On April 4, 1901, the mission steamer sailed

to Risk Point, off the shore of the village of Dopima. Immediately the

ship was surrounded by natives. Tamate promised to come ashore in the

morning. The next day, both Tomkins and Tamate went ashore, saying they

would return shortly for breakfast. After a certain interval had passed,

as if by prearrangement, the natives who remained on the ship looted it,

taking all of the stores of presents and Tamate's and Tomkins's

belongings. The captain, alarmed by the prolonged absence of the two

missionaries and by the conduct of the natives, was further concerned when

he saw a large number of warriors getting into canoes. He suspected that

the missionaries had been murdered and that the next targets were he and

his shipmates. He sailed away to report to the governor. His suspicions

were confirmed a short time later by British investigators and the

testimony of captured natives from the guilty village. The missionaries

had been clubbed, beheaded, and eaten.

The news of Chalmers's

murder made headlines all over the world. Those who had worked closely

with Chalmers were shocked and grieved at the news of his death, but felt

strongly that he would have wished to die as he did -- engaged in service

to the natives of New Guinea. As an old friend wrote: "Hitherto God had

preserved him; now he allowed the blow to fall, and His faithful servant

to be called up home."

Reprinted from FAITH for the

Family (1982).

© Bob Jones University,

www.bju.edu/faith . All rights reserved.

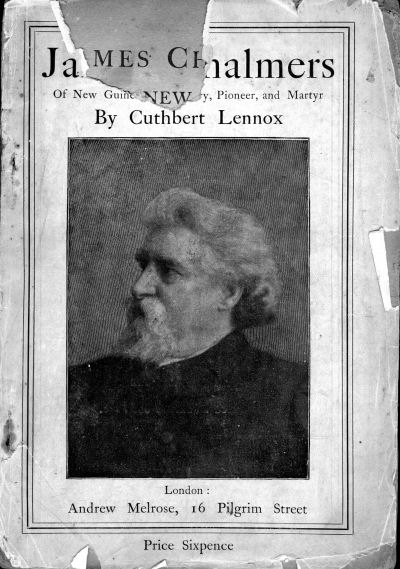

James Chalmers of New Guinea by Cuthbert

Lennox (1903)

Preface

NOT once, but a dozen times, the

writer has been asked—Who was Chalmers of New Guinea? It would seem that,

notwithstanding the numerous occasions on which this great man was

enthusiastically received at public gatherings during his visits to Great

Britain, in 1884—85 and again in

1896—97, there is a very considerable

proportion of the British people to whom he is yet unknown.

Moffat and Livingstone, Mackay of

Uganda, and Paton of the New Hebrides are universally recognised as

pioneer missionaries of the nineteenth century; and, without attempt at

the invidious task of deciding their comparative merits and their

individual rights of precedence, we claim a place for James Chalmers in

this group of missionary heroes.

When we try to account for the

prevailing ignorance in regard to one of the most interesting

personalities conceivable, one of the biggest men of last century, we

believe we find some excuse for it in the extreme modesty of the man

himself. Chalmers cared nothing for fame, and only visited this country in

1884, after an absence of twenty years, from a compelling sense of the

need for more men to exploit and occupy the field which he had surveyed

alone.

The present sketch is designed to

furnish the reading public with some idea of the splendid achievements and

attractive personality of this remarkable man. There is every reason for

supposing that the name and work and personality of "Tamate" are better

known to the citizens of the Commonwealth of Australia; but even from

them, as well as from his many friends and admirers in the home-land, a

particular and consecutive narrative of his life-story may receive a

welcome, if it serves to fill up lacuna in the information they already

possess.

For the somewhat scanty details of

the boyhood and student days of Chalmers, the writer wourd acknowledge

help received from a slender biographical sketch written a good many years

ago by the late William Robson, and published by Messrs. Partridge, and

from an article in the Sunday at Home, from the pen of the Rev.

Richard Lovett, to whom has been entrusted the preparation of the

forthcoming official life of Chalmers.

The earliest record of Tamate’s work

in New Guinea took the form of extracts from his joufnals and reports,

published in the London Missionary Society’s Chronicle, and of

articles from his pen, contributed to various periodicals and newspapers.

In 1885 he placed many of his journals and papers at the disposal of the

Religious Tract Society, "in the hope that their publication may increase

the general store of knowledge about New Guinea, and may also give true

ideas about the natives, the kind of

Christian work that is being done in

their midst, and the progress in it that is being made." In that year this

Society published Work and Adventure in New Guinea, a compilation

in which ample use was made of the journals from which the above-mentioned

extracts had been taken (with the addition of several chapters from the

pen of Dr. W. Wyatt Gill).; and in 1887 the same publishers issued a

similar compilation under the title of Pioneering in New Guinea.

Both these volumes have been out of print for a number of years, and it is

gratifying to notice that they are shortly to be republished at popular

prices.

In the preparation of his narrative

of Tamate’s earlier years in New Guinea, the writer has sought to unravel

"the bewildering record "—as Dr.

George Robson has called it—contained in the two volumes just mentioned,

obtaining from them the main facts of the period from 1878 to 1885. For

the rest, he has derived much help from the Chronicle of the London

Missionary Society, the Proceedings of the Royal Geographical

Society, and numerous other biographical aids.

Acknowledgment should also be made

of assistance received from an article contributed by Mr. G. Seymour Fort

to the Empire Review, and from an appreciation of Tamate by Dr. H.

Bellyse Baildon which recently appeared in the

Dundee Advertiser.

To furnish an intelligible

background for the portrait which it is sought to outline, and to indicate

the local conditions—missionary and otherwise—when Chalmers entered upon

his labours on Rarotonga and, later, in New Guinea, it has been deemed

desirable to include in the following pages two short chapters of general

description and missionary history.

Within the limits of the present

volume it has only been possible to indicate the main facts and splendid

purpose of Tamate’s life. The writer has learned, with great satisfaction,

that his hero has left much valuable biographical material in the hands of

his representatives, and he believes that the following pages will but

whet the appetite of the reader for perusal of the official Autobiography

and Letters.

In his verses "In memoriam" of

Chalmers. Mr. John Oxenham expresses the confidence that

"His name,

Shall kindle many a heart to equal flame;

The fire he kindled shall burn on and on,

Till all the darkness of the lands be gone,

And all the kingdoms of the earth be won,

And one."

The writer will rejoice if

this little volume, like a torch, renders humble service in helping to

pass on the kindling flame to "many a heart."

CUTHBERT LENNOX.

EDINBURGH, 18th March 1902.

CONTENTS

Chapter I

Beginnings

Birth—Parentage—Schooling—Boyish adventure—Earliest

missionary impulse—The Revival of 1859—Changed life—Christian work—

Glasgow City Missionary—Accepted by the London Missionary Society—Student

days at Cheshunt—At Highgate Institution—The spell of

Livingstone—Appointment to Rarotonga—Marriage.

Chapter II

Outward Bound

The John Williams II.—Ordination of

Chalmers—Farewells—Storm in the Channel—Final departure—The voyage to

Australia—The voyage continued—On a reef—Back to Sydney—Final wreck of the

John Williams 11.—Samoa—With "Bully" Hayes—Arrival in Rarotonga—"Tamate".

Chapter III

The South Seas Mission in 1867 and Before

The London Missionary Society—Cook’s voyages—William

Carey and the South Seas—Early missionary effort in Tahiti—Progress of the

work— Arrival of John Williams—His pioneer work—Christianity in the South

Seas—Discovery of Rarotonga—The island—Incidents in the life of John

Williams—The first resident missionaries—Rarotonga in 1834 —Williams

founds a Training College—1839 to 1867.

Chapter IV

At Rarotonga

The island in 1867—Religious condition of the

people—Work for Chalmers—Settlement on Rarotonga—Isolation—Conduct of the

Institution and its reform—The students—Routine of study—A High

School—-The printing press—The daily programme.

Chapter V

At Rarotonga.—(continued)

Chalmers goes after the young men—Crusade against

strong drink—Rechabite Society—Natives held down by debt—Chalmers prepares

a Constitution for the Island—Christian progress—Work at the

out-stations—Visit to Mangaia—Chalmers encourages the churches in

self-support and missionary interest—A contingent of students for New

Guinea—Chalmers offers to go to the New Hebrides—First call to New

Guinea—The second call accepted—Departure from Rarotonga—Experience gained

on Rarotonga—Visit to New Zealand.

Chapter VI

New Guinea in 1877 and before

The largest island in the world—Discovery and early

exploration—The island in 1 877—Its inhabitants—Founding of the New

Guinea Mission—Mr. Lawes at Port Moresby.

Chapter VII

At South Cape

Arrival in New Guinea—A tramp inland—A coasting trip—A

born explorer—Tamate’s journals—East Cape—Suau—Settlement among

cannibals—Indiscretion of native teachers—Invitation to a cannibal feast.

Chapter VIII

Exploring from South Cape

Tamate explores the south-east coast—Pioneer

methods—Visit to an Amazon settlement—Dangerous communings at Dedele—Among

hostile savages—First real inland trip—Suau proves unhealthy—Illness and

death of Mrs. Chalmers—Tamate abandons Suau.

Chapter IX

Pioneering: Ten weeks in the Interior

Port Moresby—Work of Mr. Lawes—Inland with Ruatoka—Scarcity

of carriers—Native terror—Dissipated by the missionary—The personal

influence of Tamate—The native larder—The family pig—Native

cooking—Salt-eating extraordinary—The ground covered—Rough travelling—The

savage and the evangel—Back in Port Moresby.

Chapter X

Exploring in the Gulf of Papua

Port Moresby to Bald Head—Geographical value of the

cruise—Native toilettes—Varied reception by the natives—Cannibals—Papuan

deities and eschatology.

Chapter XI

Pioneering in 1880

Visiting the eastern stations—Six weeks inland—Rafting,

and a spill on the Kemp-Welch River—Massacre at Aroma—Visit to Manumanu

and Kabadi—Famine-stricken Animarupu—Peace-making—Results of the earlier

expeditions.

Chapter XII

The Dawn

Work for big results—First converts—Peace-making at

Motumotu—Surprised by a fighting canoe—Expedition to Doura—A forward

movement—At Delena—In the thick of the fight—Maiva—Death of Kone— Port

Moresby men in far Elema—Adventurous navigation.

Chapter XIII

Errands of Justice and Mercy

The Massacre at Kalo—Estiniate of its cause—its

punishment—Tamate’s opinion of punitive

expeditions—Visit to Kabadi—In search of the Dourans—Improved conditions

at South Cape—Cannibal boatmen—Need for New Guineans as teachers—The

Institution at Port Moresby.

Chapter XIV

Work and Adventure in the Gulf: 1883

Motuan pottery—Trade with the Far West—Lakatois—Voyage

in a trading canoe—Crossing the bar at Vailala—Other sea risks—The dubu—Discovery

of the Purari—Intercourse with natives—Picture, song, and smoke—Native

salutations—The white man on exhibition—Evening prayers at Vailala—New

Guineans preach at Orokolo and Namau— A memorable scene.

Chapter XV

Placing Teachers

The Age Expedition—One hundred miles in a week—Meeting

with cannibals at the Annie River—New Guinea fever—Visit of Rev. W. W.

Gill— Round the stations with Mr. Gill—New beginnings at Kalo—Placing

teachers—Motumotu as a vantage ground—Native teachers the true

pioneers—The devotion of the native teacher—Mr. Hume Nisbet’s

testimony—Teachers as linguists—The choice of teachers—Peace at Kabadi—The

staleness of travel—Tamate’s buoyant spirit.

Chapter XVI

A Protectorate Proclaimed

Early attempts to secure annexation for New Guinea—Tamate’s

opinion—The Proclamation—Tamate’s share in its publication—Admiral

Erskine’s tribute—Testimony of Admiral Bridge—Hopes and fears— Pastoral

supervision of teachers—Sleeps at Kalo—Koapena of Aroma.

Chapter XVII

With the Special New Guinea Commission

Tamate invited to join Sir Peter Scratchley—Expeditions

with the Commissioner—Sir Peter and Koapena—The influence of Tamate—Incidents

of peril and adventure—Tamate’s prudence—Against the burning of villages—"

Ask Tamate "—More discoveries—The influence of the missionary—The Lord’s

Supper at Suau—Death of the Commissioner—Furlough.

Chapter XVIII

Tamate in England and Scotland

An enthusiastic welcome—Work and Adventure in New

Guinea: 1877— 1885—Tamate’s message to the Directors—The lion of the hour—

At the Colonial Institute—Views on "Civilisation " and on native

dress—Robert Louis Stevenson corroborates—John Williams and missionary

bonnets—Tamate at the Royal Geographical Society—Pioneering in New

Guinea—Its reception—Visit to Inveraray—Tamate calls for volunteers—The

ninety-third anniversary of the London Missionary Society—A policy of

advance—" No retreat: no retrenchment "—Return to New Guinea.

Chapter XIX

Motumotu

Tamate visits all the stations and notes

progress—Annexation proclaimed by Sir William MacGregor—His opinion of the

missionaries—Tamate’s second marriage—Se ttlement at Motumotu—Its

strategic position—The mission house at Motumotu—Serious illness of Tamate

and his wife—Motumotu to Port Moresby in an open boat—Missionary

diet—Death of Pin’s wife—Missionaries in conference.

Chapter XX

Torres Straits and Rarotonga

A cruise with the Governor—Disappointing condition of

stations in Fly River district—A great change at Saibai—In search of the

Tuger— Pioneering again—Tamate visits the Samoas and the Hervey Islands

—At Rarotonga again—A splendid reception.

Chapter XXI

With Robert Louis Stevenson

Tamate and Robert Louis Stevenson meet—A warm

friendship results— Stevenson’s opinion of Tamate—Extracts from letters to

Tamate— Stevenson commends Pioneering in New Guinea—Dr. Baildon

contrasts the friends—Their treatment of the native—Tamate’s estimate of

Robert Louis Stevenson.

Chapter XXII

Towards the Fly River

Hopeful signs at Motumotu—Visits Queensland—Wreck of

the Harrier— Fiftieth birthday—Tamate in his shirt-sleeves—The

return voyage to New Guinea—Mrs. Chalmers left in charge—Among the

cannibals of Namau—Culinary difficulties—Baptisms and teacher-training—

Arrival of the Miro—A trial trip round the stations—Serious

illness—Further testimony of Sir William MacGregor—Prospecting on the Fly

River—Last visit to Great Britain—At the City Temple—Pioneer Life and

Work in New Guinea—Return to New Guinea.

Chapter XXIII

At Saguane

Removal to Saguane, Fly River—Its advantages and

disadvantages— Natives and tinned food—The humdrum life of a mission

station— Success and progress-—Sends teachers up the Fly River—Their

fortunes—Saguane abandoned.

Chapter XXIV

The Angel of Death

Removes to Daru—Illness and death of Mrs.

Chalmers—Renewed activity—Loneliness and work—Tamate and Christian

Endeavour—Rev. O. F. Tomkins—Expedition to Aird River—Martyrdom—Supposed

cause—World-wide grief and lamentation.

Chapter XXV

Great-Heart of New Guinea

Results of Tamate’s life-work: scientific, imperial,

and missionary—His personal appearance—His personality—His faith—His hope. |