|

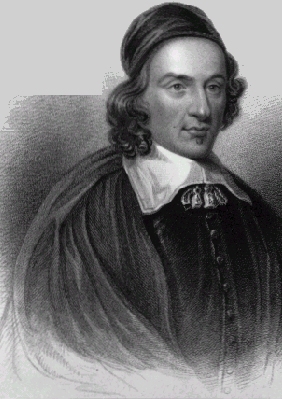

CAMPBELL,

ARCHIBALD, Marquis of Argyle, an eminent political character of the

seventeenth century, born in 1598, was the son of Archibald, seventh

earl of Argyle. He was carefully educated in a manner suitable to the

important place in society, which his birth destined him to occupy.

Having been well grounded in the various branches of classical

knowledge, he added to these, an attentive perusal of the holy

scriptures, in consequence of which his mind became at an early period

deeply imbued with a sense of religion, which, amidst all the

vicissitudes of an active and eventful life, became stronger and

stronger till his dying day. CAMPBELL,

ARCHIBALD, Marquis of Argyle, an eminent political character of the

seventeenth century, born in 1598, was the son of Archibald, seventh

earl of Argyle. He was carefully educated in a manner suitable to the

important place in society, which his birth destined him to occupy.

Having been well grounded in the various branches of classical

knowledge, he added to these, an attentive perusal of the holy

scriptures, in consequence of which his mind became at an early period

deeply imbued with a sense of religion, which, amidst all the

vicissitudes of an active and eventful life, became stronger and

stronger till his dying day.

There had long been an

hereditary feud subsisting between his family and the clan of the

Macdonalds, against whom he accompanied his father on an expedition in

the year 1616, being then only in the eighteenth year of his age; and

two years afterwards, his father having left the kingdom, the care of

the Highlands, and especially of the protestant interest there, devolved

almost entirely upon him. In 1626, he was sworn of his majesty’s most

honourable privy council, and in 1628, surrendered into the hands of the

king, so far as lay in his power, the office of justice general in

Scotland, which had been hereditary in his family, but reserving to

himself and his heirs the office of justiciary of Argyle, and the

Western Isles, which was confirmed to him by act of parliament. In 1633,

the earl of Argyle having declared himself a Roman Catholic, was

commanded to make over his estate to his son by the king, reserving to

himself only as much as might support him in a manner suitable to his

quality during the remainder of his life.

Lord Lorne, thus

prematurely possessed of political and territorial influence, was, in

1634, appointed one of the extraordinary lords of Session; and in the

month of April, 1638, after the national covenant had been framed and

sworn by nearly all the ministers and people of Scotland, he was

summoned up to London, along with Traquair the treasurer, and Roxburgh,

lord privy seal, to give advice with regard to what line of conduct his

majesty should adopt under the existing circumstances. They were all

equally aware that the covenant was hateful to the king; but Argyle

alone spoke freely and honestly, recommending the entire abolition of

those innovations which his majesty had recklessly made on the forms of

the Scottish church, and. which had been solely instrumental in throwing

Scotland into its present hostile attitude. Traquair advised a

temporizing policy till his majesty’s affairs should be in a better

condition; but the bishops of Galloway, Ross, and Brechin insisted upon

the necessity of strong measures, and suggested a plan for raising an

army in the north, that should be amply sufficient for asserting the

dignity if the crown, and repressing the insolence of the covenanters.

This alone was the advice that was agreeable to his majesty, and he

followed it out with a blindness alike fatal to himself and the

kingdom.

The earl of Argyle, being

at this time at court, a bigot to the Romish faith, and friendly to the

designs of the king, advised his majesty to detain the lord Lorne a

prisoner at London, assuring him that, if he was permitted to return to

Scotland, he would certainly do him a mischief. But the king, supposing

this advice to be the fruit of the old man’s irritation at the loss of

his estate, and probably afraid, as seeing no feasib1e pretext for

taking such a violent step, allowed him to depart in peace. He returned

to Edinburgh on the twentieth of May, and was one of the last of the

Scottish nobility that signed the national covenant, which he did not do

till he was commanded to do it by the king. His father dying this same

year, he succeeded to all his honours, and the remainder of his

property. During the time he was in London, Argyle was certainly

informed of the plan that had been already concerted for an invasion in

Scotland by the Irish, under the marquis of Antrim, who for the part he

performed in that tragical drama, was to be rewarded with the whole

district of Kintyre, which formed a principal part of the family

patrimony of Argyle. This partitioning of his property without having

been either asked or given, and for a purpose so nefarious, must have no

small influence in alienating from the court a man who had imbibed high

principles of honour, had a strong feeling of family dignity, and was an

ardent lover of his country. He did not, however, take any decisive step

till the assembly of the church, that met at Glasgow, November the

twenty first 1638, under the auspices of the marquis of Hamilton, as

lord high commissioner. When the marquis, by protesting against every

movement that was made by the court, and finally by attempting to

dissolve it the moment it came to enter upon the business for which it

had been so earnestly solicited, discovered that he was only playing the

game of the king; Argyle, as well as several other of the young

nobility, could no longer refrain from taking an active part in the work

of Reformation. On the withdrawal of the commissioner, all the privy

council followed him, except Argyle, whose presence gave no small

encouragement to the assembly to continue its deliberations, besides

that it impressed the spectators with an idea that the government could

not be greatly averse to the continuation of the assembly, since one of

its most able and influential members encouraged it with his presence.

At the close of the assembly, Mr. Henderson the moderator, sensible of

the advantages they had derived from his presence, complimented him in a

handsome speech, in which he regretted that his lordship had not joined

with them sooner, but hoped that God had reserved him for the best

times, and that he would yet highly honour him in making him

instrumental in promoting the best interests of his church and people.

To this his lordship made a suitable reply, declaring that it was not

from the want of affection to the cause of God and his country that he

had not sooner come forward to their assistance, but from a fond hope

that, by remaining with the court, he might have been able to bring

about a redress of their grievances, to the comfort and satisfaction of

both parties. Finding, however, that if was impossible to follow this

course any longer, without being unfaithful to his God and his country,

he had at last adopted the line of conduct they witnessed, and which he

was happy to find had obtained their approbation. This assembly, so

remarkable for the bold character of its acts, all of which were liable

to the charge of treason, sat twenty-six days, and in that time

accomplished all that had been expected from it. The six previous

assemblies, all that had been held since the accession of James to the

English crown, were unanimously declared unlawful, and of course all

their acts illegal. In that held at Linlithgow 1606, all the acts that

were passed were sent down from the court ready framed, and one

appointing bishops constant moderators, was clandestinely inserted among

them without ever having been brought to a vote, besides that eight of

the most able ministers delegated to attend it, were forcibly prevented

in an illegal manner by the constituted authorities from attending. In

that held at Glasgow in 1608, nobles and barons attended and voted by

the simple mandate of the king, besides several members from

presbyteries, and thirteen bishops who had no commission. Still worse

was that at Aberdeen 1616, where the most shameful bribery was openly

practised, and no less than sixteen of his creatures were substituted by

the primate of St Andrews for sixteen lawfully chosen commissioners.

That which followed at St Andrews was so notoriously illegal, as never

to have found a defender; and the most noxious of all, that at Perth in

1619, was informal and disorderly in almost all possible respects. The

chair was assumed by the archbishop of St Andrews without any election;

members, however regularly chosen and attested, that were suspected not

to be favourable to court measures, were struck out and their places

filled up by such as the managers could calculate upon being perfectly

pliable. The manner of putting the votes and the use that was made of

the king’s name to influence the voters in this most shamefully packed

assembly, were of themselves good and valid reasons for annulling its

decisions. These six corrupt convocations being condemned as illegal,

their acts became illegal of course, and episcopacy totally subverted.

Two archbishops and six bishops were excommunicated, four bishops were

deposed, and two who made humble submission to the assembly, were simply

suspended, and thus the whole Scottish bench was at once silenced. The

assembly rose in great triumph on the twentieth of December. "We

have now," said the moderator, Henderson, "cast down the walls

of Jericho; let him that rebuildeth them beware of the curse of Hiel the

Bethelite." While the assembly was thus doing its work, the

time-serving marquis of Hamilton was according to the instructions of

his master, practising all the shifts that he could devise for affording

the king the better grounds of quarrel, and for protracting the moment

of hostilities, so as to allow Charles time to collect his forces.

Preparations for an invasion of Scotland had for some time been in

progress, and in May, 1639, he approached the border with about sixteen

thousand men, while a large host of Irish papists was expected to land

in his behalf upon the west coast, and Hamilton entered the Frith of

Forth with a fleet containing a small army.

During this first

campaign, while general Lesly with the main body of the Scottish army

marched for the border with the view of carrying the war into England,

Montrose, at this time the most violent of all the covenanters, was sent

to the north to watch over Huntly and the Aberdonians, and Argyle

proceeded to his own country to watch the Macdonalds, and the earl of

Antrim, who threatened to lay it waste. For this purpose he raised not

less than nine hundred of his vassals, part of whom he stationed in

Kintyre, to watch the movements of the Irish, and part in Lorn to guard

against the Macdonalds, while with a third part he passed over into

Arran, which he secured by seizing upon the castle of Brodick, one of

the strengths belonging to the marquis of Hamilton; and this rendered

the attempt on the part of the Irish at the time nearly impossible. On

the pacification that took place at Birks, near Berwick, Argyle was sent

for to court; but the earl of Loudon having been sent up as commissioner

from the Scottish estates, and by his majesty’s order sent to the

Tower, where he was said to have narrowly escaped a violent death, the

earl of Argyle durst not, at this time, trust himself in the king’s

hands. On the resumption of hostilities in 1640, when Charles was found

to have signed the treaty of Birks only to gain time till he could

return to the charge with better prospects of success, the care of the

west coast, and the reduction of the northern clans, was again intrusted

to Argyle. Committing, on this occasion, the care of Kintyre and

the Islands to their own inhabitants, he traversed, with a force

of about five thousand men attended by a small train of artillery, the

districts of Badenoch, Athol, and Marr, levying the taxes imposed by the

estates, and enforcing subjection to their authority. The earl of Athol

having made a show of resistance at the Ford of Lyon, was sent prisoner

to Stirling; and his factor, Stuart, younger of Grantully, with twelve

of the leading men in his neighbourhood, he commanded to enter in ward

at Edinburgh till they found security for their good behaviour, and he

exacted ten thousand pounds Scots in the district, for the support of

his army. Passing thence into Angus, he demolished the castles of Airly

and Forthar, residences of the earl of Airly, and returned to

Argyleshire, the greater part of his troops being sent to the main body

in England.

In this campaign the king

felt himself just as little able to contend with his people, as in that

of the previous year; and by making concessions similar to those he had

formerly made, and, as the event showed, with the same insincerity he

obtained another pacification at Rippon, in the month of October, 1640.

Montrose, who had been disgusted with the covenanters, and gained over

by the king, now began to form a party of loyalists in Scotland,

preferring to be the head of an association of that nature, however

dangerous the place, to a second or third situation in the insurgent

councils. His designs were accidentally discovered, while he was along

with the army, and he was put under arrest. To ruin Argyle, who was the

object of his aversion, Montrose now reported, that at the Ford of Lyon

he had said that the covenanters had consulted both lawyers and divines

anent deposing the king, and had gotten resolution, that it might be

done in three cases—desertion, invasion, and vendition, and that they

had resolved, at the last sitting of parliament; to accomplish that

object next session. For this malicious falsehood Montrose referred to a

Mr John Stuart, commissary of Dunkeld, who upon being questioned

retracted the accusation which he owned he had uttered out of pure

malice, to be revenged upon Argyle. Stuart was, of course, prosecuted

before the justiciary for leasing-making, and, though he

professed the deepest repentance for his crime, was executed. The king,

though he had made an agreement with his Scottish subjects, was getting

every day upon worse terms with the English; and in the summer of 1641,

came to Scotland with the view of engaging the affections of that

kingdom to enable him to oppose the parliament with the more effect. On

this occasion his majesty displayed great condescension; he appointed

Henderson to be one of his chaplains, attended divine service without

either service-book or ceremonies, and, was liberal of his favour to all

the leading covenanters. Argyle was on this occasion particularly

attended to, together with the marquis of Hamilton, and his brother

Lanark, both of whom had become reconciled to the covenanters, and

admitted to their full share of power. Montrose, in the meantime, was

under confinement, but was indefatigable in his attempts to ruin those

whom he supposed to stand between him and the object of his ambition,

the supreme direction of public affairs. For the accomplishment of this

darling purpose, he proposed nothing less than the assassination of the

earls of Argyle and Lanark, with the marquis of Hamilton. Finding that

the king regarded his proposals with horror, he conceived the gentler

design of arresting these nobles during the night, after being called

upon pretence of speaking with him in his bed-chamber, when they might

be delivered to a body of soldiers prepared under the earl of Crawford,

who was to carry them on board a vessel in Leith Roads, or to assassinate

them if they made any resistance; but, at all events, detain them, till

his majesty had gained a sufficient ascendancy in the country to try,

condemn, and execute them under colour of law. Colonel Cochrane was to

have marched with his regiment from Musselburgh to overawe the city of

Edinburgh: a vigorous attempt was at the same time to have been made by

Montrose to obtain possession of the castle, which, it was supposed,

would have been the full consummation of their purpose. In aid of this

plot, an attempt was made to obtain a declaration for the king from the

English army, and the catholics of ireland were to have made a rising,

which they actually attempted on the same day, all evidently undertaken

in concert for the promotion of the royal cause—but all of which had

the contrary effect. Some one, invited to take a part in the plot

against Argyle and the Hamiltons, communicated it to colonel Hurry, who

communicated it to general Leslie, and he lost not a moment in warning

the persons more immediately concerned, who took precautions for their

security the ensuing night, and, next morning, after writing an apology

to the king for their conduct, fled to Kiniel House, in West Lothian,

where the mother of the two Hamiltons at that time resided. The city of

Edinburgh was thrown into a state of the utmost alarm, in consequence of

all the leading covenanters judging it necessary to have guards placed

upon their houses for the protection of their persons. In the afternoon,

the king, going up the main street, was followed by upwards of five

hundred armed men, who entered the outer hall of the Parliament house

along with him, which necessarily increased the confusion. The house,

alarmed by this military array, refused to proceed to business till the

command of all the troops in the city and neighbourhood was intrusted to

general Leslie, and every stranger, whose character and business was not

particularly known, ordered to leave the city. His majesty seemed to be

highly incensed against the three noblemen, and demanded that they

should not be allowed to return to the house till the matter had been

thoroughly investigated. A private committee was suggested, to which the

investigation might more properly be submitted than to the whole house,

in which suggestion his majesty acquiesced. The three noblemen returned

to their post in a few days, were to all appearance received into their

former state of favour, and the whole matter seemed in Scotland at once

to have dropped into oblivion. Intelligence of the whole affair was,

however, sent up to the English Parliament by their agents, who, under

the name of commissioners, attended as spies upon the king, and it had a

lasting, and a most pernicious effect upon his affairs. This, and the

news of the Irish insurrection, which speedily followed, caused his

majesty to hasten his departure, after he had feasted the whole body of

the nobility in the great hall of the palace of Holyrood, on the

seventeenth of November, 1641, having two days before created Argyle a

marquis. On his departure the king declared, that he went away a

contented prince from a contented people. He soon found, however, that

nothing under a moral assurance of the protection of their favourite

system of worship, and church government—an assurance which he had it

not in power, from former circumstances, to give—could thoroughly

secure the attachment of the Scots, who, to use a modern phrase, were

more disposed to fraternize with the popular party in England, than with

him. Finding on his return that the Parliament was getting

more and more intractable, he sent down to the Scottish privy council a

representation of the insults and injuries he had received from that

parliament, and the many encroachments they had made upon his

prerogative, with a requisition that the Scottish council would, by

commissioners, send up to Westminster a declaration of the deep sense

they entertained of the danger and injustice of their present course. A

privy council was accordingly summoned, to which the friends of the

court were more particularly invited, and to this meeting all eyes were

directed. A number of the friends of the court, Kinnoul, Roxburgh, and

others, now known by the name of Banders, having assembled in the

capital with numerous retainers, strong suspicions were entertained that

a design upon the life of Argyle was in contemplation. The gentlemen of

Fife, and the Lothians, with their followers, hastened to the scene of

action, where the high royalists, who had expected to carry matters in

the council against the English Parliament, met with so much opposition,

that they abandoned their purpose, and the king signified his pleasure

that they should not interfere in the business. When hostilities had

actually commenced between the king and the parliament, Argyle was so

far prevailed upon by the marquis of Hamilton, to trust the

asseverations which accompanied his majesty’s expressed wishes for

peace, as to be willing to second his proposed attempt at negotiation

with the Parliament, and he signed, along with Loudon, Warriston, and

Henderson, the invitation, framed by the court party, to the queen to

return from Holland, to assist in mediating a peace between his majesty

and the two houses of Parliament. The battle of Edgehill, however, so

inspirited the king, that he rejected the offer on the pretence that he

durst not hazard her person. In 1642, when, in compliance with the

request of the Parliament of England, troops were raised by the Scottish

estates, to aid the protestants of ireland, Argyle was nominated to a

colonelcy in one of the regiments, and in the month of January 1644, he

accompanied general Leslie, with the Scottish army, into England as

chief of the committee of Parliament, but in a short time returned with

tidings of the defeat of the marquis of Newcastle at Newburn. The ultra

royalists, highly offended at the assistance afforded by the estates of

Scotland, to the Parliament of England, had already planned and begun to

execute different movements in the north, which they intended should

either overthrow the Estates, or reduce them to the necessity of

recalling their army from England for their own defence. The marquis of

Huntley having received a commission from Charles, had already commenced

hostilities, by making prisoners of the provost and magistrates of

Aberdeen, and at the same time plundering the town of all the arms and

ammunition it contained, he also published a declaration of hostilities

against time covenanters. Earl Marischal, apprized of this, summoned the

committees of Angus and Mearns, and sent a message to Huntly to dismiss

his followers. Huntly, trusting to the assurances he had had from

Montrose, Crawford, and Nithsdale of assistance from the south, and from

ireland, sent an insulting reply to the committee, requiring them to

dismiss, and not interrupt the peace of the country. In the month of

April, Argyle was despatched against him, with what troops he could

raise for the occasion, and came unexpectedly upon him after his

followers had plundered and set on fire the town of Montrose, whence the

retreated to Aberdeen. Thither they were followed by Argyle, who,

learning that the laird of Haddow, with a number of his friends had

fortified themselves in the house of Killie, marched thither, and

invested it with his army. Unwilling, however, to lose time by a regular

siege, he sent a trumpeter offering pardon to every man in the garrison

who should surrender, the land of Haddow excepted. Seeing no means of

escape, the garrison accepted the terms. Haddow was sent to Edinburgh,

brought to trial on a charge of treason, found guilty, and executed.

Huntly, afraid of being sent to his old quarters in Edinburgh castle,

repaired to the Bog of Gight, accompanied only by two or three

individuals of his own clan, whence he brouight away some trunks filled

with silver, gold, and apparel, which he intrusted to one of his

followers, who, finding a vessel ready to sail for Caithness, shipped

the trunks, and set off with them, leaving the marquis to shift for

himself. The marquis, who had yet one thousand dollars, committed them

to the care of another of his dependants, and taking a small boat, set

out in pursuit of the trunks. On landing in Sutherland he could command

no better accommodation than a wretched ale-house. Next day he proceeded

to Caithness, where he found lodgings with his cousin-german, Francis

Sinclair, and most unexpectedly fell in with the runaway and his boxes,

with which by sea he proceeded to Strathnaver, where he remained in

close retirement for upwards of twelve months. In the meantime, about

twelve hundred of the promised Irish auxiliaries, under Alaster

Macdonald, landed on the island of Mull, where they captured some of the

small fortresses, and, sailing for the mainland, they disembarked in

Knoydart, where they attempted to raise some of the clans. Argyle, to

whom this Alaster Macdonald was a mortal enemy, having sent round some

ships of war from Leith, which seized the vessels that had transported

them over, they were unable to leave the country, and he himself,

with a formidable force, hanging upon their rear, they were driven into

the interior, and traversed the wilds of Lochaber and Badenoch,

expecting to meet a royal army under Montrose, though in what place they

had no knowledge. Macdonald, in order to strengthen them in numbers, had

sent through the fiery cross in various directions, though with only

indifferent success, till Montrose at last met them, having found his

way through the country in disguise all the way from Oxford, with only

one or two attendants. Influenced by Montrose, the men of Athol, who

were generally anti-covenanters, joined the royal standard in great

numbers, and he soon found himself at the head of a formidable army. His

situation was not, however, promising. Argyle was in his rear, being in

pursuit of the Irish, who were perfect banditti, and had committed

terrible ravages upon his estates, and there were before him six or

seven thousand men under lord Elcho, stationed at Perth. Elcho’s

troops, however, were only raw militia, officered by men who had never

seen an engagement, and the leaders among them were not unjustly

suspected of being disaffected to the cause. As the most prudent

measure, he did not wait to be attacked, but went to meet Montrose, who

was marching through Strathearn, having commenced his career by

plundering the lands, and burning the houses of the clan Menzies. Elcho

took up a position upon the plain of Tippermuir, where he was attacked

by Montrose, and totally routed in the space of a few minutes. Perth

fell at once into the hands of the victor, and was plundered of money,

and whatever was valuable, and could be carried away. The stoutest young

men he also impressed into the ranks, and seized upon all the horses fit

for service. Thus strengthened, he poured down upon Angus, where he

received numerous reinforcements. Dundee he attempted, but finding there

were troops in it sufficient to hold it out for some days, and dreading

the approach of Argyle, who was still following him, he pushed north to

Aberdeen. Here his covenanting rage had been bitterly felt, and at his

approach the committee sent off the public money and all their most

valuable effects to Dunnottar castle. They at the same time threw up

some rude fortifications, and had two thousand men prepared to give him

a warm reception. Crossing the Dee by a ford, he at once eluded their

fortifications and deranged their order of battle; and issuing orders

for an immediate attack, they were defeated, and a scene of butchery

followed which has few parallels in the annals of civilized warfare. In

the fields, the streets, or the houses, armed or unarmed, no man found

mercy: the ragged they killed and stripped; the well-dressed, for fear

of spoiling their clothes, they stripped and killed.

After four days employed

in this manner, the approach of Argyle, whom they were not sufficiently

numerous to combat, drove them to the north, where they intended to take

refuge beyond the Spey. The boats, however, were all removed to the

other side, and the whole force of Moray was assembled to dispute the

passage. In this dilemma, nothing remained for Montrose but to take

refuge among the hills, and his rapid movements enabled him to gain the

wilds of Badenoch with the loss only of his artillery and heavy baggage,

where he bade defiance to the approach of any thing like a regular army.

After resting a few days, he again descended into Athol to recruit,

having sent Macdonald into the Highlands on the same errand. From Athol

he entered Angus, where he wasted the estates of lord Couper, and

plundered the house of Dun, in which the inhabitants of Montrose had

deposited their valuables, and which also afforded a supply of arms and

artillery. Argyle, all this while, followed his footsteps with a

superior army, but could never come up with him. He, however, proclaimed

him a traitor, and offered a reward of twenty thousand pounds for his

head. Having strengthened his army by forced levies in Athol, Montrose

again crossed the Grampians, and spreading devastation along his line of

march, attempted once more to raise the Gordons. In this he was still

unsuccessful, and at the castle of Fyvie, which he had taken, was at

last surprised by Argyle and the earl of Lothian, who, with an army of

three thousand horse and foot, were within two miles of his camp, when

he believed them to be on the other side of the Grampians. Here, had

there been any thing like management on the part of the army of the

Estates, his career had certainly closed, but in military affairs Argyle

was neither skilful nor brave. After sustaining two assaults from very

superior numbers, Montrose drew off his little army with scarcely any

loss, and by the way of Strathtbogie plunged again into the wilds of

Badenoch, where he expected Macdonald and the Irish with what recruits

they had been able to raise. Argyle, whose army was now greatly weakened

by desertion, returned to Edinburgh and threw up his commission in

disgust. The Estates, however, received him in the most friendly manner,

and passed an act approving of his conduct.

By the parliament which

met this year, on the 4th of June, Argyle was named, along with the

chancellor Loudoun, lords Balmerino, Warriston, and others, as

commissioners, to act in concert with the English parliament in their

negotiations with the king; but from the manner in which he was

occupied, he must have been able to overtake a very small part of the

duties included in the commission. Montrose no sooner found that Argyle

had retired and left the field clear, than, to keep up the spirit of his

followers, and to satiate his revenge, he marched them into Glenorchy,

belonging to a near relation of Argyle, and in the depth of winter

rendered the whole country one wide field of blood: nor was this

destruction confined to Glenorchy; it was extended through Argyle and

Lorn to the very confines of Lochaber, not a house he was able to

surprise being left unburned, nor a man unslaughtered. Spalding adds,

"he left not a four-footed beast in the haill country; such as

would not drive he houghed and slew, that they should never make

stead." Having rendered the country a wilderness, he bent his way

for Inverness, when he was informed that Argyle had collected an army of

three thousand men, and had advanced as far as Inverlochy, on his march

to the very place upon which he himself was advancing. Montrose was no

sooner informed of the circumstance, than, striking across the

almost inaccessible wilds of Lochaber, he came, by a march of about six

and thirty hours, upon the camp of Argyle at Inverlochy, and was within

half a mile of it before they knew that there was an enemy within

several days’ march of them. The state of his followers did not admit

of an immediate attack by Montrose; but every thing was ready for it by

the dawn of day, and with the dissolving mists of the morning. On the

second of February, 1645, Argyle, from his pinnace on the lake, whither

he had retired on account of a hurt he had caught by a fall from his

horse, which disabled him from fighting, beheld the total annihilation

of his army, one half of it being literally cut to pieces, and the other

dissipated among the adjoining mountains, or driven into the water.

Unable to afford the smallest assistance to his discomfitted troops, he

immediately hoisted sails and made for a place of safety. On the twelfth

of the month, he appeared before the parliament, then sitting in

Edinburgh, to which he related the tale of his own and their misfortune,

in the best manner no doubt which the case could admit of. The

circumstances, however, were such as no colouring could hide, and the

Estates were certainly deeply affected. But the victory at Inverlochy,

though as complete as victory can well be supposed, and gained with the

loss too of only two or three men, was perhaps more pernicious to the

victors than the vanquished. The news of it unhappily reached Charles at

a time when he was on the point of accepting the terms of reconciliation

offered to his parliament, which reconciliation, if effected, might have

closed the war for ever, and he no sooner heard of this

remarkable victory, than he resolved to reject them, and trust to

continued hostilities for the means of obtaining a more advantageous

treaty. Montrose, also, whose forces were always reduced after a

victory, as the Highlanders were wont to go home to deposit their

spoils, could take no other advantage of "the day of Inverlochy,"

than to carry on, upon a broader scale, and with less interruption, the

barbarous system of warfare which political, religious, and feudal

hostility had induced him to adopt. Instead of marching towards the

capital, where he might have followed up his victory to the utter

extinction of the administration of the Estates, he resumed his march

along the course of the Spey into the province of Moray, and, issuing an

order for all the men above sixteen and below sixty to join his

standard, under the pain of military execution, proceeded to burn the

houses and destroy the goods upon the estates of Grangehill, Brodie,

Cowbin, Innes, Ballendalloch, Foyness, and Pitchash. He plundered also

the village of Garmouth and the lands of Burgie, Lethen, and Duffus, and

destroyed all the boats and nets upon the Spey. Argyle having thrown up

his commission as general of the army, which was given to general

Baillie, he was now attached to it only as member of a committee

appointed by the parliament to direct its movements, and in this

capacity was present at the battle of Kilsyth, August 15th, 1645, the

most disastrous of all the six victories of Montrose to the Covenanters,

upwards of six thousand men being slain on the field of battle and in

the pursuit. This, however, was the last of the exploits of the great

marquis. There being no more detachments of militia in the country to

oppose to him, general David Leslie, with some regiments of horse, were

recalled from the army in England, who surprised and defeated him at

Philiphaugh, annihilating his little army, and, according to an

ordinance of parliament, hanging up without distinction all the Irish

battalions.

In the month of February,

1646, Argyle was sent over to Ireland to bring home the Scottish troops

that had been sent to that country to assist in repressing the

turbulence of the Catholics. He returned to Edinburgh in the month of

May following. In the meantime, Alister Macdonald, the coadjutor of

Montrose, had made another tour through his country of Argyle, giving to

the sword and the devouring flame whatever had escaped in the former

inroads, so that upwards of twelve hundred of the miserable inhabitants,

to escape absolute starvation, were compelled to emigrate, under one of

their chieftains, Ardinglass, into Menteith, where they attempted to

settle themselves upon the lands of the malignant. But scarcely had they

made the attempt, when they were attacked by Inchbrackie, with a party

of Athol men, and chased beyond the Forth near Stirling, where they were

joined by the marquis, who carried them into Lennox, and quartered them

upon the lands of lord Napier, till he obtained an act to embody them

into a regiment, to be stationed in different parts of the Highlands,

and a grant from parliament for a supply of provisions for his castles.

So deplorably had his estates been wasted by the inroads of Montrose and

Macdonald, that a sum of money was voted him for the support of himself

and family, and for paying annual rents to some of the more necessitous

creditors upon his estates. A collection was at the same time ordered

through all the churches of Scotland, for the relief of his poor people

who had been plundered by the Irish. In the month of July, 1646, when

the king had surrendered himself to the Scottish army, Argyle went up to

Newcastle to wait upon and pay his respects to him. On the 3d of August

following, he was sent up to London, along with Loudon, the chancellor,

and the earl of Dunfermline, to treat with the parliament of England,

concerning a mitigation of the articles they had presented to the

king, with some of which he was not at all satisfied. He was also on

this occasion the bearer of a secret commission from the king, to

consult with the duke of Richmond and the marquis of Hertford concerning

the propriety of the Scottish army and parliament declaring for him.

Both of these noblemen totally disapproved of the scheme, as they were

satisfied it would be the entire ruin of his interests. In this matter,

Argyle certainly did not act with perfect integrity; and it was probably

a feeling of conscious duplicity which prevented him from being present

at any of the committees concerning the king’s person, or any treaty

for the withdrawal of the Scottish army, or the payment of its arrears.

The opinion of these two noblemen, however, he faithfully reported to

his majesty, who professed to be satisfied, but spoke of adopting some

other plan, giving evident proof that his pretending to accept

conditions was a mere pretence—a put off—till he might be able to

lay hold of some lucky turn in the chapter of accidents. It was probably

from a painful anticipation of the fatal result of the king’s

pertinacity, that Argyle, when he returned to Edinburgh and attended the

parliament, which assembled on the 3d of November, demanded and obtained

an explicit approval of all that he had transacted, as their accredited

commissioner; and it must not be lost sight of, that, for all the public

business he had been engaged in, except what was voted him in

consequence of his great losses, he never hitherto had received one

farthing of salary.

When the Engagement, as

it was called, was entered into by the marquis of Hamilton, and other

Scottish presbyterian loyalists, Argyle opposed it, because, from what

he had been told by the duke of Richmond and the marquis of Hertford,

when he had himself been half embarked in a scheme somewhat similar, he

believed it would be the total ruin of his majesty’s cause. The event

completely justified his fears. By exasperating the sectaries and

republicans, it was the direct and immediate cause of the death of the

king.. On the march of the Engagers into England, Argyle, Eglinton,

Cassilis, and Lothian, marched into Edinburgh at the head of a great

multitude of people whom they had raised, before whom the committee of

Estates left the city, and the irremediable defeat of the Engagers,

which instantly followed, entirely sinking the credit of the party, they

never needed to return; the reins of government falling into the hands

of Argyle, Warriston, Loudon, and others of the more zealous party of

the presbyterians. The flight of the few Engagers who reached their

native land, was followed by Cromwell, who came all the way to Berwick,

with the purpose apparently of invading Scotland. Argyle, in the month

of September or October, 1648, went to Mordington, where he had an

interview with that distinguished individual, whom, along with general

Lambert, he conducted to Edinburgh, where he was received in a way

worthy of his high fame, and every thing between the two nations was

settled in the most amicable manner, the Solemn League and Covenant

being renewed, the Engagement proscribed, and all who had been concerned

in it summoned to appear before parliament, which was appointed to meet

at Edinburgh on the 4th of January, 1649. It has been, without the least

particle of evidence, asserted that Argyle, in the various interviews he

held with Cromwell at this time, agreed that Charles should be executed.

The losses to which Argyle was afterwards subjected, and the hardships

he endured for adhering to Charles’ interests after he was laid

in his grave, should, in the absence of all evidence to the contrary, be

a sufficient attestation of his loyalty, not to speak of the parliament,

of which he was unquestionably the most influential individual, in the

ensuing month of February proclaiming Charles II. king of Scotland,

England, France, and Ireland, &C. than which nothing could be more

offensive to the then existing government of England. In sending over

the deputation that waited upon Charles in Holland in the spring of

1649, Argyle was heartily concurring, though he had been not a little

disgusted with his associates in the administration, on account of the

execution of his brother-in-law, the marquis of Huntly, whom he in vain

exerted all his influence to save. It is also said that he refused to

assist at the trial, or to concur in the sentence passed upon the

marquis of Montrose, in the month of May, 1650, declaring that he was

too much a party to be a judge in that matter. Of the leading

part he performed in the installation of Charles II., upon whose head he

placed the crown at Scone on the 1st of January, 1651, we have

not room to give any particular account. Of the high consequence in

which his services were held at the time, there needs no other proof

than the report that the king intended marrying one of his daughters.

For the defence of the king and kingdom, against both of whom Cromwell

was now ready to lead all his troops, he, as head of the Committee of

Estates, made the most vigorous exertions. Even after the defeat at

Dunbar, and the consequent ascendancy of the king’s personal

interests, he adhered to his majesty with unabated zeal and diligence,

of which Charles seems to have been sensible at the time, as the

following letter, in his own hand writing, which he delivered to Argyle

under his sign manual, abundantly testifies:—"Having taken into

consideration the faithful endeavours of the marquis of Argyle for

restoring me to my just rights, and the happy settling of my dominions,

I am desirous to let the world see how sensible I am of his real respect

to me by some particular marks of my favour to him, by which they may

see the trust and confidence which I repose in him: and particularly, I

do promise that I will make him duke of Argyle, knight of the garter,

and one of the gentlemen of my bed-chamber, and this to be performed

when he shall think it fit. And I do farther promise him to hearken to

his counsels, [passage worn out]. Whenever it shall please God to

restore me to my just rights in England, I shall see him paid the

£40,000 sterling which is due to him; all which I promise to make good

to him upon the word of a king. CHARLES REX, St Johnston, September

24th, 1650." When Charles judged it expedient to lead the Scottish

army into England, in the vain hope of raising the cavaliers and

moderate presbyterians in his favour, Argyle obtained leave to remain at

home, on account of the illness of his lady. After the whole hopes of

the Scots were laid low at Worcester, September 3d, 1651, he retired to

Inverary, where he held out against the triumphant troops of Cromwell

for a whole year, till, falling sick, he was surprised by general Dean,

and carried to Edinburgh. Having received orders from Monk to attend a

privy council, he was entrapped to be present at the ceremony of

proclaiming Cromwell lord Protector. A paper was at the same time

tendered him to sign, containing his submission to the government, as

settled without king or house of lords, which he absolutely refused,

though afterwards, when he was in no condition to struggle farther, he

signed a promise to live peaceably under that government. He was

always watched, however, by the ruling powers, and never was regarded by

any of the authorities as other than a concealed loyalist. When Scotland

was declared by Cromwell to be incorporated with England, Argyle exerted

himself, in opposition to the council of state, to have Scotsmen

alone elected to serve in parliament for North Britain, of which Monk

complained to Thurlow, in a letter from Dalkeith, dated September

30, 1658. Under Richard he was himself elected for the county of

Aberdeen, and took his seat accordingly in the house, where he wrought

most effectually for the service of the king, by making that breach

through which his majesty entered. On the Restoration, Argyle’s best

friends advised him to keep out of the way on account of his compliances

with the Usurpation; but he judged it more honourable and honest to go

and congratulate his majesty upon so happy a turn in his affairs. To

this he must have been misled from the promissory note of kindness which

he held, payable on demand, as well as by some flattering expressions

which Charles had made use of regarding him to his son, lord Lorn; but

when he arrived at Whitehall, July 8, 1660, the king no sooner heard his

name announced, than, "with an angry stamp of the foot, he ordered

Sir William Fleming to execute his orders," which were to carry him

to the Tower. To the Tower he was carried accordingly, where he lay till

the month of December, when he was sent down to Leith aboard a

man-of-war, to stand his trial before the high court of parliament.

While confined in the Tower, the marquis made application to have the

affidavits of several persons in England taken respecting some matters

of fact, when he was concerned in the public administration before the

usurpation, which, had justice been the object of the prosecution

against him, could not have been denied. Revenge, however, being the

object, facts might have happened to prove inconvenient, and the request

was flatly refused.

On his arrival at Leith,

he was conveyed to the castle of Edinburgh, and, preparatory to his

being brought to trial, the president of the committee for bills, on the

eighteenth of January, reported to the parliament that a supplication

had been presented to them by the laird of Lamont, craving warrant to

cite the marquis of Argyle, with some others, to appear before

parliament, to answer for crimes committed by him and them as specified

in the bill given in. Some little opposition was made to this; but it

was carried by a vast plurality to grant warrant according

to the prayer of the petition. This charge could not be intended to

serve any other purpose than to raise a prejudice in the public mind

against the intended victim; for it was a charge which not a few of the

managers themselves knew well to be false. Middleton could have set the

question at once to rest, as he had had a deeper hand in many of the

cruelties complained of than Argyle, for he had acted under general

Leslie, in suppressing the remains of Montrose’s army, and, much

nearer home than the islands, namely at Kincardine house, belonging to

Montrose, had shot twelve cavaliers without any ceremony, sending the

remainder to be hanged at Edinburgh, all which, be it observed, was in

defence of a party of Argyle’s people who had been driven to seek

refuge in Lennox, and was no doubt one of the items in the general

charge. But the charge generally referred to the clearing of his own

territories of Alister Macdonald and his Irish bands by Leslie, who, in

reducing the strengths belonging to the loyalists in the north, had,

conformably to the orders of parliament, shot or hanged every Irishman

he found in them without ceremony. Sir James Turner, who was upon this

expedition, and has left an account of it in his Memoirs, acquits Argyle

of all blame, in so far as concerns the seizure of the castle of

Dunavertie, one of the cases that has been most loudly complained of,

though he fastens a stain on the character of Mr John Nevoy, the divine

who accompanied the expedition, who, he says, took a pleasure in wading

through the blood of the victims. A small extract will show that Leslie

confined himself strictly to the parliamentary order, which was perhaps

no more severe than the dreadful character of the times had rendered

necessary. "From Ila we boated over to Jura, a horrid isle, and a

habitation fit for deer and wild beasts, and so from isle to isle till

we come to Mull, which is one of the best of the Hebrides. Here Maclean

saved his lands with the loss of his reputation, if he ever had any: he

gave up his strong castles to Leslie; gave his eldest son for hostage of

his fidelity, and, which was unchristian baseness in the lowest degree,

he delivered up fourteen very pretty Irishmen, who had been all along

faithful to him, to the lieutenant general, who immediately caused hang

them all. It was not well done to demand them from Maclean; but

inexcusably ill done in him to betray them. Here I cannot forget one

Donald Campbell, fleshed in blood from his very infancy, who, with all

imaginable violence, pressed that the whole clan Maclean should be put

to the sword, nor could he be commanded to forbear his bloody suit by

the lieutenant general and two major generals, and with some difficulty

was he commanded silence by his chief, the marquis of Argyle. For my

part, I said nothing, for indeed I did not care though he had prevailed

in his suit, the delivering of the Irish had so much irritated me

against that whole clan and name." Argyle was brought before

parliament on the 13th of February 1661. His indictment, consisting of

fourteen articles, comprehended the history of all the transactions that

had taken place in Scotland since 1638. The whole procedure, on one side

of the question, during all that time, had already been declared

rebellion, and each individual concerned was of course liable to the

charge of treason. Middleton, lord high commissioner to parliament,

eager to possess his estate, of which he doubted not he would obtain the

gift, conducted the trial in a manner not only inconsistent with

justice, but with the dignity and the decency that ought ever to

characterise a public character. From the secret conversations he had

held with Cromwell, Middleton drew the conclusion, that the interruption

of the treaty of Newport and the execution of Charles had been the fruit

of their joint deliberations. He was defended on this point by Sir John

Gilmour, president of the court of Session, with such force of argument

as to compel the reluctant parliament to exculpate him from all blame in

the matter of the king’s death; and, after having exhibited the utmost

contempt for truth, and a total disregard of character or credit,

provided they could obtain their point, the destruction of the pannel,

the crown lawyers were at length obliged to fix on his compliance with

the English during the usurpation, as the only species of treason that

could at all be made to affect him. Upon this point there was not one of

his judges who had not been equally, and some of them much more guilty

than himself: "How could I suppose," said the marquis, with

irresistible effect in his defence on this point, "that I was

acting criminally, when the learned gentleman who now acts as his

majesty’s advocate, took the same oaths to the commonwealth with

myself ?" He was not less successful in replying to every iota of

his indictment, in addition to which he gave in a signed supplication

and submission to his majesty, which was regarded just as little as his

defences. The moderation, the good sense, and the magnanimity, however,

which he displayed, joined to his innocence of the crimes charged

against him, wrought so strongly upon the house, that great fears were

entertained that, after all, he would be acquitted; and to counteract

the influence of his two sons, lord Lorne and lord Neil Campbell, who

were both in London, exerting themselves as far as they could in his

behalf, Glencairn, Rothes, and Sharpe were sent up to court, where, when

it was found that the proof was thought to be defective, application was

made to general Monk, who furnished them with some of the marquis of

Argyle’s private letters, which were sent down post to Middleton, who

laid them before parliament, and by this means obtained a sentence of

condemnation against the noble marquis, on Saturday the 25th, and he was

executed accordingly on Monday the 27th of May, 1661. Than the behaviour

of this nobleman during his trial, and after his receiving sentence of

death, nothing could be more dignified or becoming the character of a

christian. Conscious of his integrity, he defended his character and

conduct with firmness and magnanimity, but with great gentleness and the

highest respect for authority. After receiving his sentence, when

brought back to the common jail, his excellent lady was waiting for him,

and, embracing him, wept bitterly, exclaiming, "the Lord will

requite it;" but, calm and composed, he said, "Forbear; truly,

I pity them; they know not what they are doing; they may shut me in

where they please, but they cannot shut out God from me. For my part, I

am as content to be here as in the castle, and as content in the castle

as in the Tower of London, and as content there as when at liberty, and

I hope to be as content on the scaffold as any of them all." His

short time till Monday he spent in serenity and cheerfulness, and in the

proper exercises of a dying christian. To some of the ministers he said

that they would shortly envy him for having got before them, for he

added, "my skill fails me, if you who are ministers will not either

suffer much, or sin much; for, though you go along with those men in

part, if you do it not in all things, you are but where you were, and so

must suffer; and if you go not at all with them, you shall but

suffer." On the morning of his execution, he spent two hours in

subscribing papers, making conveyances, and forwarding other matters of

business relating to his estate; and while so employed, he suddenly

became so overpowered with a feeling of divine goodness, according to

contemporary authority, that he was unable to contain himself, and

exclaimed, "I thought to have concealed the Lord’s goodness, but

it will not do: I am now ordering my affairs, and God is sealing my

charter to a better inheritance, and saying to me, ‘Son, be of good

cheer; thy sins are forgiven thee.’" He wrote the same day a most

affecting letter to the king, recommending to his protection his wife

and children. "He came to the scaffold," says Burnet, "in

a very solemn, but undaunted manner, accompanied with many of the

nobility and some ministers. He spoke for half an hour with a great

appearance of serenity. Cunningham, his physician, told me that he

touched his pulse, and it did then beat at the usual rate, calm and

strong." It is related, as another proof of the resolution of

Argyle, in the last trying scene, that, though he had eaten a whole

partridge at dinner, no vestige of it was found in his stomach after

death; if he had been much affected by the anticipation of death, his

digestion, it may be easily calculated, could not have been so good. His

head was struck off by the instrument called the Maiden, and affixed on

the west end of the Tolbooth, where that of Montrose had been till very

lately perched; a circumstance that very sensibly marks the vicissitudes

of a time of civil dissension. His body was conveyed by his friends to

Dunoon, and buried in the family sepulchre at Kilmun.

Argyle, with few

qualities to captivate the fancy, has always been esteemed by the people

of Scotland as one of the most consistent and meritorious of their array

of patriots. For the sake of his exemplary moral and religious

character, and his distinguished exertions in the resistance to the

measures of Charles I., as well as his martyrdom in that cause, they

have overlooked a quality generally obnoxious to their contempt—his

want of courage in the field—which caused him, throughout the whole of

the transactions of the civil war, to avoid personal contact with

danger, though often at the head of large bodies of troops. The habits

of Argyle in private life were those of an eminently and sincerely pious

man. In Mr Wodrow’s diary of traditionary collections, which remains

in manuscript in the Advocates’ Library, it is related, under May 9,

1702, upon the credit of a clergyman, the last survivor of the General

Assembly of 1651, that his lordship used to rise at five, and continue

in private till eight: besides family worship, and private prayer,

morning and evening, he prayed with his lady morning and evening, in the

presence of his own gentleman and her gentlewoman; he

never went abroad, though but for one night, without taking along with

him his writing-standish, a bible, and Newman’s Concordance. Upon the

same authority, we relate the following anecdote: "After the

coronation of king Charles II. at Scone, he waited a long time for an

opportunity of dealing freely with his majesty on religious matters, and

particularly about his suspected disregard of the covenant, and his

encouragement of malignants, and other sins. One sabbath night, after

supper, he went into the king’s closet, and began to converse with him

on these topics. Charles was seemingly sensible, and they came at length

to pray and mourn together till two or three in the morning. When he

came home to his lady, she was surprised, and told him she never knew

him so untimeous. He said he never had had such a sweet night in the

world, and told her all—what liberty he had in prayer, and how much

convinced the king was. She said plainly that that night would cost him

his head—which came to pass." Mr Wodrow also mentions that,

during the Glasgow Assembly, Henderson and other ministers spent many

nights in prayer, and conference with the marquis of Argyle, and he

dated his conversion, or his knowledge of it, from those times. His

lordship was married to Margaret, second daughter of William, second

earl of Morton, and by her left two sons and three daughters. |