The night was very dark, but from the deepest of the

darkness, the shadow of the trees on the opposite bank, came the sounds of

the dragging of the nets and the handling of the boat, by men who spoke not

a word. Suddenly, the two young men broke the night air with their challenge

across the river, "Who the hell are you?"

They could get no answer, and then they blazed with their

guns, with the unfortunate result that three at least of the offenders were

peppered with shot. One, a very decent man called John Fraser, was shot by

thirty or forty pellets over the head and face, and he was injured in the

left eye so severely that the eye had to be removed, and there was a danger

to the other eye, and so of complete loss of sight. The circumstances were

these.

Two sons of an American millionaire had fired by night at

a party of Scottish gamekeepers, peppering them well and blinding one to the

loss of one eye and to the danger of another. On this kind of superficial

view, Scotland was ablaze with the wrath and Mr Phipps’ two sons, who were

implicated in the transaction, were arrested.

Behold then a telegram! It was from my clerk asking

whether I would accept a retainer for the two young millionaires. It may

give people some idea of the efficiency of Scottish criminal justice when I

mention that the offence was committed on July 5th of the year

1905, and the investigations were complete and the trial took place at the

High Court in Edinburgh in the following month, the trial taking only one

day and concluding on the evening of August 29th.

The case was as follows. The Phipps family who had

Beaufort Castle for about eight years, were tenants not only of the shooting

but also of the right of angling on the River Beauly. This fishing was one

of the finest in Scotland, and the right over one or two pools cost Mr

Phipps Senior, over £2,000 per annum.

One evening his two sons, strong and handsome specimens

of vigorous manhood, heard voices on the river and they suspected some

outrage was being committed — that, in fact, this valuable fishing pool,

known as "The Silver Pool" outside the very windows of the castle, was being

dragged with nets. They accordingly rallied forth armed as described, by way

of the gun room and to the river bank.

Beaufort Castle

Mr Phipps Senior asked me to come to Beaufort Castle—and

this I did so as to see for myself the place of the affray. I went to that

most beautiful residence on the banks of the River Beauly, and there I was

conducted from the hall, down the stairs to the gun room. I then was told

that it was from this gun room that the two young gentlemen, having heard

sounds of dragging salmon in the river, had emerged on the river bank, and

that each of them in passing through had taken his gun and a pocketful of

cartridges.

There was little else to see except the bank of the

river, on the opposite side of which a dark group of trees—which I might

easily conceive in the dim evening light would throw an extremely dark

shadow—attracted my attention. It turned out that it was in that very shadow

that the shooting took effect.

The next part of the story is peculiar. There turned out

to have been six men engaged in the operation of dragging the pool. Who were

these men?

It sounds incredible, but they were actually the servants

of Lord Lovat, the proprietor of the river and fishings and castle, and they

were engaged in dragging the pool in the river with nets, the angling on

which by rod yielded their master more than £2,000 of rent. But the wonder

does not stop there, for they were not poachers in the ordinary sense—that

is, for their own profit; they were all respectable men, and they were

deliberately dragging the pool so as to keep up the average of fish caught

in the river for the credit of the river and the estate, and the fish caught

in the net—forty in number in the last haul—were not sold for their own

profit, but they were taken and put into the estate account, number and

value complete.

As the situation developed before the Jury, the case took

a very different aspect as one might suppose, but still stranger things were

to happen…

As the trial proceeded, I shall never forget the entry of

Fraser, the injured man, into the Court. He was guided to the witness-stand

and gave his evidence perfectly quietly. It was my duty to cross-examine

him, and he in no way fenced. He was asked by me and afterwards by the Judge

why he did not answer the call across the river. He admitted he knew it was

young Mr Phipps that called, that Mr Phipps had for years been his friend,

and that he was young Mr Phipps’ own fishing attendant.

But it then came out, as was by this time suspected, that

so far as concealment from the Phipps family was concerned, the whole matter

was literally a deed of darkness in which these men were engaged; they had

not hinted to anybody about the netting expedition.

The head keeper with five other men under his orders, of

whom Fraser was one, had proceeded to the river. Fraser’s position was the

humble one of having to obey his head keeper’s orders. Upon the keeper being

pressed for some kind of reason for his conduct, he put forward the theory -

for which there is a good deal in fishing circles to be said - that the pool

was too crowded with salmon to be in a healthy condition and that dragging

would do it good. The difficulty about this was that if it was to do the

pool good for angling they might at least have informed Mr Phipps or some

member of his family.

As it was the six of them began their operations, forty

fish were caught, and three men went off with the forty fish to the nearest

ice-house, and three were left, one of whom was Fraser, another Robertson,

and a third whose name I forget.

When the young gentlemen emerged on the river side, they

went to the waters edge, called across, and getting no answer, fired.

This seems very dreadful, but the defence adopted the

line, which the Bench accepted, that the number of shots indicated no desire

to injure but merely to scare the men from the river, and Lord Ardwell on

the Bench charged the Jury that scaring in that sense was a good means of

getting poachers to abandon their enterprise and leave their nets, which

could then be impounded. All this was a difficult line of legal country; and

one had to pick their steps with care.

The next fact - a somewhat crucial one - now emerged. The

ordinary breadth of the river at the point of fishing was a hundred yards,

and to fire across that distance with an ordinary fowling piece would have

been a noisy and innocuous proceeding. The river, however, was very low, and

as it happened, at that particular point where the accused emerged from the

door of the castle on the river bank, its breadth that evening had narrowed

to a space of forty yards. In the dark the men had advanced on to the

water’s edge before they fired, and the case was that their firing was a

scaring operation, and that there was no real recklessness about it, as the

assumed breadth of the river would have made the whole proceeding harmless…

[Ed: According to two independent sources in

Beauly, the building next to the Lovat Estates Office, acquired by the

Phipps family, was subsequently donated to the town. Known as the Phipps

Institute, it serves as a community hall and library.]

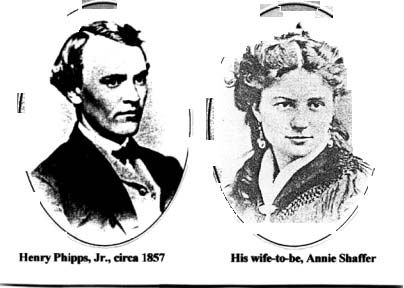

Henry Phipps & his future bride

Henry Phipps (1839-1930) was a capitalist and

philanthropist. Henry Phipps, Jr., the son of master shoemaker Henry Phipps

and his wife Hannah, from England, was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on

27 Sep 1839 and grew up in Pittsburgh. In 1845 the Phipps family moved to

Allegheny City, PA where they became next-door neighbours of the Carnegie

family from Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. Henry started as an office boy in

Pittsburgh and formed a lasting friendship with Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919),

then also an office boy.

Phipps became a partner of Carnegie in the development of

iron and steel manufacture and contributed to their association, the

financial genius to raise and control the capital necessary to their

progress.

On 6 Feb 1872, Henry Phipps married Anne Childs Shaffer,

the daughter of a Pittsburgh manufacturer, by whom he had three sons and two

daughters. Like Carnegie, Phipps became a well known philanthropist. He

amassed $100 million and gave $7 million to charity. He retired in 1900 with

more than forty million dollars and divided much of his estate among his

three sons in 1912. Jay, his eldest son, built Westbury House on Long Island

[American Heritage, November 1987, Rich Kids, by Barbara Klaw and

Halcyon Days, by Harry N. Abrams, chronicle the lives of the young

Phippses]. Westbury House and gardens are now open to the public.

Henry Phipps died 22 Sep 1930 at his estate "Bonnie

Blink" in the Lakefield section of Great Neck, Long Island, survived by his

widow, nee Anne C. Shaffer; two daughters, Mrs. Frederick Guest and Mrs.

Bradley Martin, and three sons, John S., Henry C., and Howard Phipps. He was

buried on Sept 24th at Westbury, L.I. (Protestant Episcopal

Church of the Advent).

Thanks to Marie

Fraser, Clan Fraser

Society of Canada for this article.