The Father

of Auckland

(Written for the “N.Z. Railways Magazine,” by

James Cowan)

“I sign this Deed of Gift on the 61st anniversary of the year I left the Maori village of Waiomu, on the shores of the Hauraki Gulf, and entered the primeval forest to carve with my axe the canoe in which I afterwards made my way to the island of Motu-korea, my first home in the Waitemata.”

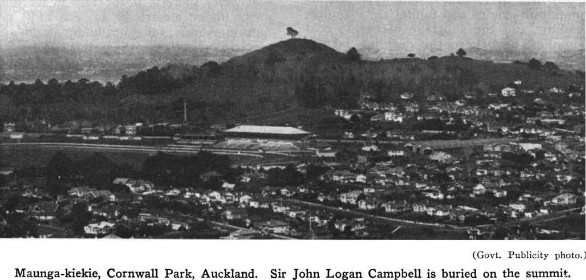

With these simple yet eloquent words the venerable Dr. John Logan Campbell, Auckland's earliest settler, concluded the document which endowed his city with the noblest park and pleasure ground in New Zealand, the Maunga-kiekie estate, known as Cornwall Park, in honour of the Royal visit to the Dominion in 1901. He was knighted in the following year and died in 1912, at the age of ninety-four, and was buried on the summit of the hill park, the crowning beauty of the Greater Auckland plains.

Sir John Logan Campbell.

Auckland” has been fortunate over all the other cities of the Dominion in the benevolent and generous character of its pioneer citizens, and the wonderful old man who came to be called “The Father of Auckland” was in some respects the finest of them all, and certainly the most munificent. He was not a politician, except for short periods in the early years of the province; his activities lay in the building up of the city and the development of its institutions and its prosperity. He saw the Waitemata before ever a house or even a tent stood on the site of Auckland. No other colonist was so closely associated with the foundation and the fostering of great business enterprises and the practical making of the country which he saw in its primitive condition and whose growth he watched over a period of nearly three quarters of a century.

“The Doctor,” as he was often called even after he became Sir John, was a true pioneer in the sense that he saw and felt much of the rough end of life and enjoyed it all, and in the midst of his prosperity and his manifold activities preserved the spirit of simplicity and the love of the out-of-doors, the bush and the old free days of Maoridom. He was to his last days a man of methodical habits and simple tastes. He cultivated the arts, he was a friend of many a great man in the literary world, he stood before princes, but he never lost his touch with the common things of life.

Physically the grand old man was an example to the younger generation, the leg-tired and the luxury-loving. Even when he was well on his eightieth year, and I think even later, he walked daily from his home at Kilbryde, in Parnell, to his office in the city, climbing that “stey brae” Constitution Hill on the way, a sufficiently stiff test of soundness of wind and limb. He had a dark little office in Shortland Street, as close as might be to the spot where he pitched his tent amongst the manuka and ferns in 1840, and sank his water-barrel in the spring from which he filled his tea-billy though they didn't call it a billy in those days. There one used to see him, on occasion, in the Nineties, sitting there like some sagacious old sage, with his long white locks and beard, gathering in the threads of his many businesses, but ever ready to talk of the far romantic past, when time didn't matter on the shores of the Hauraki.

Campbell's Early Days.

Sir John Logan Campbell came of a family whose ancestral home was Kilbryde Castle, in Perthshire, a fortified home dating back four centuries. His forefathers, as was natural in that Highland stronghold, were mostly soldiers, a long line of them until it came to his father, who was an army surgeon and who had retired from the service to practice in Edinburgh. There John Logan was born in 1817. He studied for his father's profession, obtained his M.D., and became a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons. He obtained a commission in the East India Company's Service, but abandoned that intention and instead decided to try his fortune in the far-south colonies. He sailed from Greenock in 1839 as surgeon of the ship “Palmyra,” bound for Sydney.

A very few months in New South Wales were enough for him. He did not like the convict associations of the Australian settlement, and New Zealand beckoned. He took passage in a vessel called the “Lady Lilford,” of 596 tons, which reached Wellington Harbour from Sydney in March, 1840, and after a few days there —it was not called Wellington then but “Britannia,” the rough little settlement on Petone beach—sailed for the Hauraki Gulf. In April he landed at Herekino Bay, in Waiau or Coromandel Harbour, and that was the beginning of his long career as a settler and citizen of the country that he came to love even more intensely than he did his native land. There on the shore of Waiau he took up his quarters with a trader who was the big man of the Hauraki in that primitive age, when the Waitemata Harbour was all but unknown and when Waiheke Island and Waiau were the chief resorts of the ships which every now and again came to load kauri spars for Australia, India or England.

Where Big Webster Lived.

Many years ago, on a summer boating cruise about the islands at the entrance to Coromandel, I searched out the site of the long-vanished pakeha-Maori village of Herekino. It is on Beeson's Island, that long, hilly island which forms the western warden of Waiau Harbour and all but meets a long arm of the mainland. The island, now a sheep run, has many a grove of great pohutukawa, and some of these glorious old trees shade the deserted beach of Herekino. The old-time kainga is gone: gone too is the shipbuilding yard at the island-tip where cutters and schooners were built long before a shipwright set up business on the shores of the Waitemata. But a beautiful spring of clear cool water bubbles up close to the white beach as it did in the days when Big Webster was the King of Waiau. The narrow channel between the point and the mainland is called the Little Passage; a few strokes of the dinghy oars takes one across it. Campbell's description in his book “Poenamo” of Coromandel and Beeson's Island and Herekino when he arrived there in 1840, mentions this tiny strait of water, “a narrow passage between the island and the mainland, so narrow that I was often afterwards navigated across it on the back of a Maori wahine when none of the male sex was at hand.”

Here in the pretty bay of Herekino lived and reigned the King of Waiau, William Webster, a tall Yankee, an ex-whaleship-carpenter, called Big Webster by the pakehas and Wepiha by the Maoris. His royal power consisted of the goods in his trading-store or “whare-hoko”; his mana was high all around the Hauraki. Webster's name became celebrated in after years in connection with a huge claim (made through the United States Government) against the New Zealand Government for compensation for disallowed land purchase made before 1840, a claim that failed.

The Glories of the Waitemata.

In his book “Poenamo”—a mutilated but musical version of the Maori word for greenstone—Campbell gives a series of pictures full of charm of his pioneer life on the shore of the Hauraki and his first year in infant Auckland. His narrative tells of the Herekino pakeha-Maori establishment, of a boat cruise to Waiheke Island and the then lonely and unspoiled Waitemata, of his first walk across the Tamaki isthmus to the Manukau, of camping life among the Maoris, and of the truly primitive and happy days in the midst of the Maoris at Waiomu. His pen lingered with delight and regret on the glories of the forest, the noble kauri, the fragrant fern tree dells of the bush that then came down to the very water's edge. He describes leisurely canoe voyaging about the shores of Tamaki, and tells how he came to know the true inwardness and import of that sometimes delectable and often exasperating word “taihoa.”

There is a wistful note, a sigh for untouched beauty passed away, in Campbell's chapter in “Poenamo” describing his first day on the harbour where New Zealand's largest city spreads over its hills and plains.

“How lovely and peaceful were Waitemata's sloping shores as we explored them on that now long, long ago morning! As we rowed over her calm waters the sound of our oars was all that broke the stillness. No, there was something more—the voices of four cannie Scotsmen and one shrewd Yankee (the sum and substance of the first invading civilisation) loud in the praise of the glorious landscape which lay before them. On that morning the open country stretched far away in vast fields of fern, and nature reigned supreme…. We rowed up the beautiful harbour close in shore. No sign of human life that morning; the shrill cry of the curlew on the beach, and the full rich carol of the tui, or parson-bird, from the brushwood skirting the shore fell faintly on the ear.”

Remuera as it was.

Campbell and his friends fell in love with the delectable Remuera, then as now the most beautiful harbour-facing part of the Tamaki isthmus. He tried in vain to buy those slants, for which the Maori has also that pleasing name Ohinerau, “The Place of Many Girls.”

“Beautiful was Remuera's shore,” wrote the Doctor, “sloping gently to Waitemata's sunlit waters in the days of which I write. The palm fern-tree was there with its crown of graceful bending fronds and black feathery-looking young shoots; and the karaka, with its brilliantly-polished green leaves and golden-yellow fruit, contrasting with the darker crimped and varnished leaf of the puriri, with its bright cherrylike berry. Evergreen shrubs grew on all sides, of every shade from palest to deepest green; lovely flowering creepers mounted high overhead, leaping from tree to tree and hanging in rich festoons; of beautiful ferns there was a profusion underfoot. The tui, with his grand rich note made the wood musical; the great fat stupid pigeon cooed down upon you almost within reach, nor took the trouble to fly away.”

Te Hira and the Mess of Pottage.

Had it not been for a certain fateful pot of stewed pigeon, which made a meal for the pakeha land-seekers at Orakei on the cruise of 1840, young Dr. Campbell might have become the owner of the site of Auckland city. The story is told in “Poenamo.” It must have been a noble stew, for half a bottle of wine was poured into it to complete the feast. (Campbell's partner believed in carrying some home comforts into the wilds.) But there was a young chief there named Te Hira, son of the old patriarch, Te Kawau. When the pakehas had finished their meal some of the stew remained, and Te Hira took possession of the pot intending to enjoy what his visitors had left. One of them, wishing to give the food to one of his Maori crew, asked the chief why he was taking the pot away, but in his blundering way, not knowing much of the language, he used the word “tahae,” which means to steal. This gave great offence to the young man; he retired in anger and sulks. Next day the party embarked in Webster's boat, taking Te Hira with them, and rowed up the harbour past the shores on which the city now stands. They looked at all the snug bays and the pretty headlands and asked “Won't you sell this?” and “Won't you sell that?” and the reply was always a refusal “Kahore, kahore!” Te Hira was one of the principal land-owners and nothing could be done without him. So there was nothing for it but to retire, and back the land hunters sailed to Orakei and thence home to Waiau. A few months later the Ngati-Whatua, headed by Te Kawau and Te Hira, sold the site of Auckland to the Government, and so began the town. By that time Campbell and his partner had purchased from the chiefs of the Ngati-Tamatera

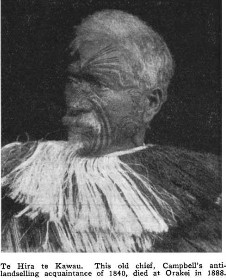

Te Hira te Kawau. This

old chief, Campbell's antilandselling acquaintance

of 1840, died at Orakei in 1888.

tribe at Waiomu, south of Coromandel, a small island at the entrance to the Waitemata, called Motu-korea, now so well known as Brown's Island. And as there was no boat to be procured—Big Webster had none to spare—the two pakehas perforce set to to chop out a canoe of their own, from a kauri tree which had been felled in the forest near the Waiomu village. When this canoe was completed, after many weeks' labour with axe and adze, they set out for their little island kingdom, in a new boat built by a pakeha-Maori in Webster's employ which towed their home-made craft across the gulf.

The description of their first camp on Motukorea, and of the pride with which they explored their estate, is one of the most charming parts of Campbell's eloquent yet unaffected story.

A word about Te Hira, of mess-of-pottage fame. I remember well that aristocratic-looking rangatira of Orakei in his old age, a white-moustached richly-tattooed chief, uncle of the leading spirit of the village, Paul Tuhaere. Te Hira saw the land that he would not sell to Campbell become a great city.

For himself, he troubled little about land or Maori politics. His chief delight and occupation was fishing. He was forever out in his boat, anchored at some favourite fishing ground, line out, pipe in mouth, dozing away the easy days, waiting for the snapper or the kingfish to hook themselves on.

In Infant Auckland.

But Motu-korea and the pigs with which the Maoris stocked it for the pakehas did not hold Campbell and Brown long. Immediately this tented town was founded, they paddled up in their canoe and established themselves as settlers and traders. They bought a section facing Shortland Street, then just a track in the manuka scrub, and so began the new life that made them wealthy merchants under the style of Brown and Campbell. A humble beginning to a great career was Campbell's first year in the baby capital. The story of his rise to prosperity and fame is practically the story of Auckland. He had a hand in every important public service and was one of the chief founders of several great commercial and financial institutions, among them the Bank of New Zealand and the New Zealand Insurance Company. His firm owned ships, both sail and steam, and carried on a large export trade in kauri timber from the Kaipara. He bought land, and the first large purchase he made was the now famous Maunga-kiekie.

What memories must have come to him when in his last years he drove over the slopes of the great park that will memorise for all time his generous patriotism and gazed upon the thickly populated isthmus, practically one continuous city from the Waitemata to the Manukau, that within his own recollection was quite unpeopled except for a few Maori hapus on the shores! He saw Auckland built up from nothing to a city of a hundred thousand people, and no man helped more materially in this building than he. His services were not merely parochial or provincial. That he had the prophetic soul of the true statesman was more abundantly manifest in his writings and his public utterances.

The Gift of Maunga-kiekie.

The patriarch's gifts to his home city amount in cash value, it has been estimated, to at least

a quarter of a million pounds. But his benefactions to Auckland are not to be measured in mere cash values. The noble park, fair in the heart of greater Auckland, which he made over to the people in 1901, is a really priceless public endowment. It has several names. Totara-iahua is the sharp summit, the ancient tihi or citadel of the great chief Kiwi Tamaki; the hill is Maunga-kiekie (“Mount of the climbing plant Freycinetia Banksii”); the local popular name is One-Tree Hill, and at the donor's request it was renamed Cornwall Park in honour of the Royal visitors. But a more fitting name now would be Campbell Park, and that is what one would like to see it generally styled in the future. It is a very lovely place, this softly green and partly-wooded hill, rising in tier after tier of terraces and in curves shady with tall trees; a wonderful relic of Maori military engineering genius which made of this volcanic cone a fortress, with line after line of escarpments which in some places resemble great amphitheatres, round about the ancient craters. Campbell left a bequest of £5,000 to erect a great obelisk to the memory of the glory of the Maori race on the crest of the mountain, but what better memorial can there be than the hill itself? The fortifications so clearly traceable to-day extend about a hundred acres. This is only a small portion of the parklands that circle around the tree-crowned mountain top where the grand old man sleeps, for as is fitting he was laid to rest on the summit. There we may imagine his spirit lingers to keep watch over the plain of Tamaki-makau-rau. To him how well applies the epitaph linked with the name of Sir Christopher Wren, “Si monumentum quaeris, circumspice.” At the main entrance to the park there is a statue to his memory, but the park itself is his sufficient monument.