NATURAL Science is not,

as it is often asserted to be, fatal to the doctrines of revealed

religion. It is true there are men, distinguished by research and

discovery in the heavens and the earth, who ignore the Bible as beneath

the labour of refutation, or speak of it patronisingly as the production

of semi-barbarians who were skilled in fine poetic legends, but were so

ill-instructed as to write in opposition to the facts of the universe.

But there are others not less qualified for forming accurate judgments,

and not less eminent in scientific attainments, who see beautiful

correspondencies between the Word and the works of God; and find in the

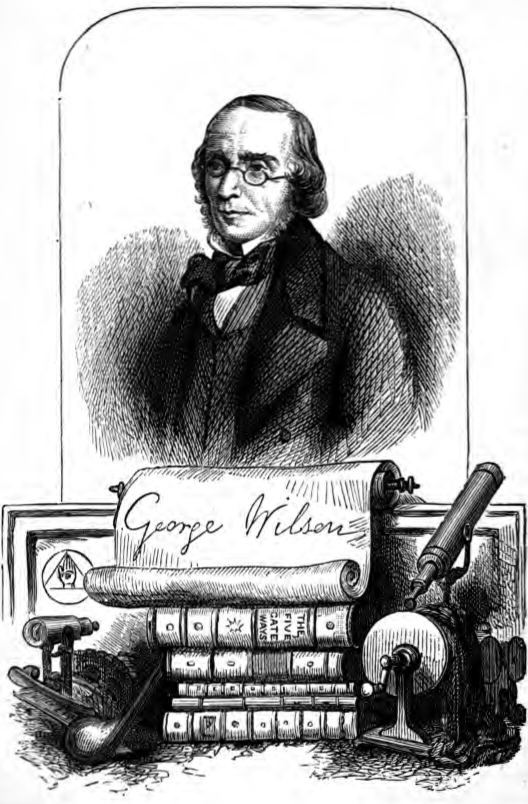

latter a thousand confirmations of the truth of the former. George

Wilson is entitled to rank with those who have gone deep into the

mysteries of Creation, and have at the same time confessed and rejoiced

in the Divine authority and the saving virtue of the Gospel.

He was born in Edinburgh, February 21st, 1818. His mother was endowed

with a superior mind, and manifested unostentatious, yet deep,

life-pervading piety. George was one of a twin birth, and it was his

mother’s custom every night to visit the cot in which the brothers

slept, when she repeated over them the memorable words of aged Jacob:

“The God which fed me all my life long unto this day, the Angel which

redeemed me from all evil, bless the lads.” Her home, with the exception

of sorrows occasioned by family bereavements, was a peculiarly happy

one. A tender affection subsisted between the brothers and sisters, and

they were encouraged in pursuits at once entertaining and instructive.

They had their pets, such as a hedgehog, tortoise, guinea-pig, an owl,

and white mice. Their home enjoyments were also heightened by a good

supply of interesting books, and a small museum, for which they

collected such natural and artificial curiosities as came within their

reach. The boys had many delightful rambles in the neighbourhood of

Edinburgh; and Leith sands, the banks of the Forth, woods, and straths,

and ruined castles, haunted by the stirring memories of Scottish heroes

and sovereigns, afforded them a varied and ever new delight. They also

enjoyed occasional visits to the manse of Cumbernauld in Dumbartonshire,

where they displayed such vigour and joyousness that as they went along

the village the boys and girls used to cry out, “Look! there’s the braw

callants.” George early showed a love of books, and an old nurse said of

him, “O, as for George, he was aye to be seen in a comer wi’ a book as

big’s himsel’! ” After receiving a respectable education at the High

School, he had to make choice of a profession, and decided to be a

physician. He was placed as an apprentice in the laboratory of the Royal

Infirmary. Having to accompany the surgeons through the wards, his

sensitive heart was often tortured by the suffering he witnessed, but he

had the satisfaction of performing some benevolent actions. A young

sailor underwent amputation of a leg, and some days after the operation

George went to see him, and found him busily engaged in polishing a shoe

for his one remaining foot. He became interested in him, and spent a few

shillings he had reserved for the purchase of Coleridge’s “Aids to

Reflection,” which he was anxious to obtain, in buying comforts for him.

When discharged it was found that his clothes were detained for arrears

of lodging. George raised a subscription to help him out of this

difficulty, and took him home for a night, giving him hospitable

entertainment before setting sail for the Isle of Wight, where his

mother and sister resided; from whom he received a beautiful letter of

thanks for his kindness.

A German died in the Infirmary. There were no friends to claim the body,

and on that account it was to be doomed to the dissecting knife. George

had been impressed by the beauty of the man’s countenance, and could not

bear the thought of its being cut and mangled in the dissecting room. He

found some Germans who were waiters in one of the clubs of the town, and

told them that if they would claim the body and inter it, the clothes of

the deceased would refund them for their outlay. The men acted according

to the suggestion, and grateful for the consideration that had been

shown for the corpse of a fellow-countryman, they offered George the

best reward it was in their power to give,—“O Sir! is there nothing we

could do for you? Would you like to see the club-room?”

In September, 1837, having passed the prescribed examination, he was

registered as a surgeon, and took a situation as clerk in the Infirmary;

but still continued his studies, “busied in the difficulties of several

of the physical sciences, changing from pharmacy to chemistry, from

chemistry to physiology, or taking a refreshment in the subtilities of

logic, or the elegancies of rhetoric thus showing himself singularly

free from what Burke calls “that master-vice, sloth.” Chemistry was his

favourite pursuit, and he thus playfully refers to his partiality for

that science: “Nevertheless, she is descended from a noble and

influential family of very ancient origin, which can show incontestable

proofs of having flourished in the dark ages, under another title, and

which received great additions to its power and influence, under the

reigns of Elizabeth and James I., under the chancellorship of Lord

Bacon. If you wish to see the birth, descent, and fortunes of the

family, I would refer you, not to Burke’s Peerage, but to the

Encyclopaedia, where, under the article ‘ Sciences,’ you will find a

minute history of the family; and if you ask me which of the daughters

has awakened in me such admiration, I reply, ‘the Right noble the

Science of Chemistry,’ who, in my eyes, is by far the most attractive

and interesting of the family.” In 1838 he went to London, where he

engaged himself as assistant in Professor Graham’s laboratory. He there

became intimate with a student who is now worthy of honour as the brave,

yet peaceful Africanus of our age. In after years, a volume of travels

was sent to him bearing this inscription, “To Professor G. Wilson, with

the kindest regards of his friend and class-mate, David Livingstone.”

Though Mr. Wilson was diligent in chemical researches and experiments,

he was not so absorbed in them as to be unable to heed the whispers of

the poetic muse. Some snowdrops having been given to him, he repaid the

donor in verses embodying a fancy, which though not in literal

accordance with the facts of creation, is beautiful as a poetic dream.

His imagination took him back to Eve, shivering with the cold of the

first winter she had known, and lamenting her exclusion from Eden with

its golden year, its amaranths and asphodels, but cheered by the

apparition of a benign angel, who, bidding her banish her sorrows,

caught a flake of f ailing snow, and breathing on it caused it to

flutter to the earth as a lovely white flower.

"This is an earnest, Eve,

to thee,’

The glorious angel said,

That sun and summer soon shall be;

And though the leaves seem dead,

Yet once again the smiling spring

With wooing winds, shall softly bring

New life to every sleeping thing ;

Until they wake and make the scene

Look fresh again and gaily green.’

“The angel’s mission being ended,

Up to heaven he flew;

But where he first descended,

And where he bade the earth adieu,

A ring of snowdrops formed a posy

Of pallid flowers, whose leaves unrosy,

Waved like a winged argosy,

Whose climbing masts, above the sea,

Spread fluttering sail and streamer free.

"And thus the snowdrop, like the bow,

That spans the cloudy sky,

Becomes a symbol whence we know

That brighter days are nigh;

That circling seasons, in a race

That knows no lagging, lingering pace,

Shall each the other nimbly chase,

Till time’s departing, final day,

Sweep snowdrops and the world away.”

Mr. Wilson returned to

Scotland, and took his degree as Doctor of Medicine, but did not attempt

to gain practice, for his predilections were still in favour of

Chemistry, and he awaited an opening as lecturer on that science. At

length the object of his ambition was attained, and he lectured in a

school connected with the Queen’s College Edinburgh; but the strain at

the beginning was very severe. Writing to a friend he says: “For the

last fortnight I have not had a moment to give to anything but my

lectures. I have lectured six days every week, besides teaching a

practical class, and instructing private pupils. This excess of labour

has compelled me to sit up every night till two o’clock, and rise at

seven; and so tired am I when I come home at four o’clock, that I often

fall asleep on the sofa while dinner is being served. But it was not

long before he had to contend with affliction as well as weariness. In a

walking tour in Perthshire, he sprained his foot, an apparently slight

accident, the effect of which lie felt painfully to the end of his life;

and in addition to this, he was tortured by rheumatism and inflammation

of one eye. As long as possible he kept bravely to his public duties,

dictating his lectures to his sister while he lay in bed, or on a sofa;

going after nights of anguish, unrelieved by a moment’s sleep, to -the

Lecture Hall, where he lectured standing on one foot, or leaning on a

crutch. At last, however, he had to retire. He thus described his

position. “Just struck down unexpectedly from all my hopes. I cannot

look hopefully to the future, and must recover the stun and shock of my

fall, before I become alive to all the comforts that surround me; but

know this at least for your consolation, that though often despondent, I

do not repine, and do never seek enviously to contrast my own position

with that of others. This much of peace of mind God has granted me, and

I trust He will vouchsafe patience and courage to bear all that is sent

me. I believe that, even for this world, all noble characters are

perfected through suffering; and in that spirit I try to endure all

things. But flesh is weak, and I know this too well to vaunt anything at

present.”

Though his body was racked by pain, his intellect was in full vigour,

and the tedium of his retirement was relieved by excursions into the

domains of Science and Literature. He could summon at will the mighty

spirits of philosophers and poets to his couch; but what was of far more

importance, his affliction brought him into closer contact with the

great matters of religious belief and experience; and in those hours of

pain and weariness, his mind and heart were permeated by the spirit of a

new and blessed life* From childhood his conduct had been blameless, and

he never lost the influence of his godly home, but he had not sought a

personal union with Christ as “Wisdom, righteousness, sanctification,

and redemption;” but when laid low by that afflictive dispensation of

Providence, and saddened by the prospect of a painful operation, the

amputation of his foot, he was induced to cast his soul in humble

penitence and faith on the atoning grace of the Lord Jesus.

The process of his spiritual enlightenment and saving trust in the

Redeemer has been in part recorded by Dr. Cairns, who was then in

Edinburgh preparing himself for that work in which he has won such a

distinguished name. “ General conversation was often succeeded by

discussions such as might be expected from a student of Divinity

visiting a pious family; and though George took at first little or no

part in these, gradually he began to feel interested; and we used to

have long and earnest talks when others had withdrawn. I cannot recall

accurately his religious difficulties. He had no sceptical tendency,

beyond a general inability to reconcile the Gospel as miraculous with

the uniformity of nature; and I think, too, that some misgivings

disturbed him as to the doctrine of the atonement. But his great want

was the power to realise the value of the Gospel remedy, from his heart

having been greatly set on literary and scientific eminence. God took

His own way to abate this hindrance by sending ill-health, and thwarting

all his plans of rapid elevation. A very slow yet steady increase of

interest in eternal things now set in; an extraordinary change took

place in his use of the Bible. The phrase quoted in his ‘ Life of John

Reid/ that he ‘had a sair wark wi’ his Bible/ describes his own state

exactly; and we used to discuss many passages. He was especially devoted

to the Epistle to the Hebrews, which he valued for its clear view of the

atonement, and of the sympathy of Christ; and no part of his Bible is so

much worn, this being indeed almost worn away.....I remember with vivid

accuracy, the earnestness with which on the last occasion I saw liim

before the operation, he spoke of the danger before him, and of the

great anxiety, mingled with trembling hope in Christ, which he showed as

to his spiritual state.”

After the amputation, Dr. Cairns was able to announce that the mind of

the sufferer was all peace and joy. “If that be the result,” said the

mother, “all is well.” Dr. Wilson bore his loss with Christian

resignation, and years after he thus beautifully wrote of it: “There is

no day so painful to me to recall as the first of January, so far as

suffering is concerned. It was on it, eleven years ago, that the disease

in my foot reappeared with the severity which in a few days thereafter

compelled its loss, and the season always comes back to me as a very

solemn one; yet if, like Jacob, I halt as I walk, I trust that like him

I came out of that awful wrestling with a blessing I never received

before; and you know that if I were to preach my own funeral sermon, I

should prefer to all texts, ‘It is better to enter halt into life, than

having two feet to be cast into hell, into the fire that never shall be

quenched.' When convalescent he resumed his scientific lectures, but

pulmonary affection sadly interfered with the pleasure he would

otherwise have had in them, and often after returning from the

exhausting duties of the Lecture Hall, he would say, “Well, there’s

another nail put into my coffin.” But the efforts which wore him down

gave high satisfaction to his hearers. His range of information, the

simplicity of his illustrations and experiments, his ability to steep

the facts of science in the hues of poetry, ensured for him large

audiences. Previous to one of his lectures a crowd was assembled on the

outside of the building, and he requested permission to pass. The people

seeing only an insignificant man, in anything but professional costume,

refused, and he was obliged to tell them that if they did not let him

pass they would get no lecture. On another occasion a number of boys

were about the door as he was going in, and one of them asked in

imploring tones, “Eh, man, will ye no let us in?” but one with keener

eyes said, “That’s no a man, that’s a gentleman.”

But it was not by the multitude alone, to whom his expositions were a

novelty, that he was admired; such men as Dr. Chalmers and Lord Jeffrey

acknowledged his powers and were proud of his friendship; while his

“Researches on Colour-blindness ” won for him a high place in the

scientific world. He regretted that the state of his health allowed him

to do so little in connection with the Church he had joined, that of Dr.

Alexander; but he wrote: “I have found a means of doing good that I hope

God will bless. I discovered recently that sick people who will not

stand a word of religious advice from their neighbours in health, are

more ready to listen to another sick man like me.” And by kindly

sympathising letters, he was able, by the help of God, to communicate

blessing to several invalids.

In 1848 he gave a lecture before the Edinburgh Medical Missionary

Society, on “ The Sacredness of Medicine as a Profession.” He closed it

with these impressive sentences: “I adjure you to remember that the head

of our profession is Christ. He left all men an example that they should

follow His steps; but He left it specially to us. It is well that the

statues of Esculapius and Hippocrates should stand outside of our

College of Physicians, but the living image of our Saviour should be

enshrined within. He is not ashamed to call us brethren; may none of us

be ashamed to call Him Lord. May we all confess Him before men, that He

may confess us before the angels in heaven.” He had afterwards the

satisfaction of learning that the lecture had carried conviction to the

heart of a hitherto careless medical man. In 1854, while spending a

little time at Rothesay, he accidentally broke his arm. He received this

additional affliction as a mild chastening from his Heavenly Father, and

in the silence of a sleepless night composed “The Camera Obscura,” of

which the following are the closing verses:

“So within thy dark

recesses,

Clothed in His robes of white,

To the sufferer, Christ appeareth,

In a new and blessed light,

Which the glare of day outshining

Hid from His unshaded sight.

“Silent, dimly-lighted chamber,

Like the living eye,

If thou wert not dark, no vision

Could be had of things on high ;

By the untempered daylight blinded,

With closed eyelids we should die.

“O, my God! light up each chamber

Where a sufferer lies,

By Thine own eternal glory

Tempered for those tearful eyes

As it comes from Him reflected

Who was once the Sacrifice.”

Though frequently brought

low by severe illnesses, Dr. Wilson was ready at every partial recovery

to return to his public duties. The vigour of his mind triumphed over

the feebleness of his body, and though worn and wasted by disease, he

threw himself into his employment with the ardour and energy of a

stalwart man. He looked on affliction, not as an excuse for apathy, but

as a preparation for higher service. “The furnace of affliction puffs

away some men in black smoke, and hardens others into useless slags, and

melts a few into clear glass. May it refine us into gold seven times

purified, ready to be fashioned into vessels for the Master’s use.”

In 1855 he was appointed to the Directorship of the Scottish Industrial

Museum; an appointment including a chair of Technology. The spirit in

which he entered on his new duties is apparent in a passage of liis

inaugural lecture: “Institutions like all other things grow faster in

these days than they did of old; but perennial things are still slow of

growth, and the most enduring the slowest of all. We must be content to

pluck the first-fruits, and leave the full harvest to be gathered by

those who follow. But that its first and last fruits may alike conduce

to the glory of God and the good of man, is my earnest prayer; and,

therefore, we will confide it to Him Who, eighteen hundred years ago,

dignified and made honourable the humblest craft, by permitting Himself

to be called the Son of the Carpenter, and Who now stretches forth His

Divine Hand to bless all honest, earnest, labour.”

While busied with the affairs of the Museum, he published his little

book entitled, “The Five Gateways of Knowledge.” His pen was at

different times employed on other books and papers, but “The Five

Gateways” is his most popular work. Eight thousand copies were sold in a

few years, and it is still extensively read. It abounds in useful

information and suggestions, and is written in a style so simple, yet

graphic and poetic, as to have the fascination of a fairy tale.

He struggled with his tasks to the year 1859, when he had a severe

attack of pleurisy and inflammation of the lungs. Though he had long

been dying daily, he thought at first that he should again be raised up;

but the sickness was unto death. Happily he was ready for the change.

His sister bending over him when there was no longer any hope said,

“You’re going home, dear.” He replied, “I have been an unworthy servant

of a worthy and gracious Master.” Soon after this, while Dr. Cairns, his

mother and sister watched by his bedside, his soul glided away, and he

entered into rest. His own beautiful paraphrase of Paul’s description of

the whole armour of God, was to him no longer an anticipation, but a

joyful experience:

“Helmet of the hope of

rest!

Helmet of salvation!

Nobly has thy towering crest

Pointed to this exaltation.

Yet I will not thee resume

Helmet of the nodding plume ;

Where I go no foeman fighteth,

Sword or other weapon smiteth;

All content, I lay thee down,

I shall bind my brows with an immortal crown.

“Sword at my side! Sword of the Spirit!

Word of God! Thou goodly blade!

Often have I tried to merit;

Never hast thou me betrayed.

Yet I will no farther use thee,

Here for ever I unloose thee:

Branch of peaceful palm shall be

Sword sufficient unto me ;

Fought the fight, the victory won,

Best thou here, thy work is done.

"Shield of faith! my trembling heart

Well thy battered front has guarded;

Many a fierce and fiery dart

From my bosom thou hast warded.

But I shall no longer need thee,

Never more will hold or heed thee.

Fare-thee-well! the foe’s defeated

Of his wished-for victim cheated;

In the realms of peace and light,

Faith shall be exchanged for sight.

“Girdle of the truth of God!

Breastplate of His righteousness!

By the Lord Himself bestowed

On His faithful witnesses;

Never have I dared to unclasp thee,

Lest the subtle foe should grasp me;

Now I may at length unbind ye,

Leave you here at rest behind me;

Naught shall harm my soul equipped

In a robe in Christ’s blood dipped.

"Sandals of the preparation

Of the news of peace!

There must now be separation,

Here your uses cease.

Gladly shall my naked feet

Go my blessed Lord to meet;

I shall wander at His side

Where the living waters glide ,

And those feet shall need no guard

On the unbroken, heavenly sward,

"Here I stand of all unclothed,

Waiting to be clothed upon,

By the Church's great Betrothed,

By the everlasting One.

Hark! He turns the admitting key,

Smiles in love and welcomes me;

Glorious forms of angels bright

Clothe me in the raiment white;

Whilst their sweet-toned voices say,

'For the rest wait thou till the judgment day.'” |