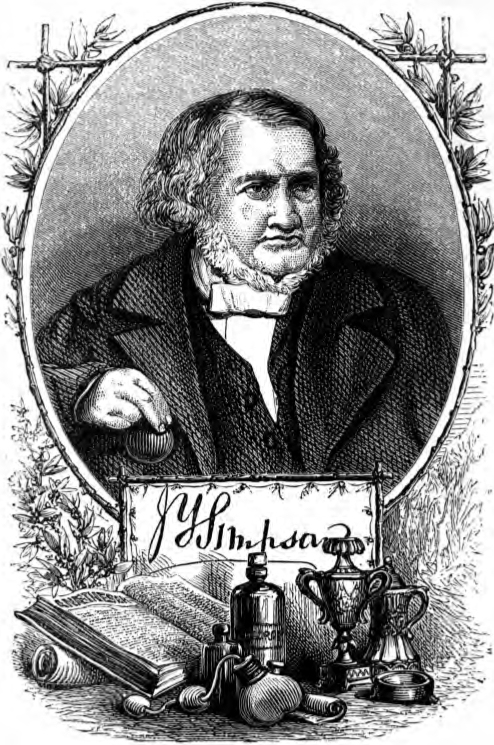

JAMES YOUNG SIMPSON, “the

beloved physician,” was born at Bathgate, in Linlithgowshire, on June

7th, 1811. His father, the son of a small fanner, was a baker, and

though a worthy man, was unable to conduct the business so as to make it

support his family. At the time of James’ birth the drawings in the shop

were so small that he could no longer conceal the state of affairs from

his wife, who hitherto had kept strictly within the sphere of domestic

duty. She was a sagacious, energetic woman, and at once devised means by

which he was able to get rid of his most pressing difficulties. Under

her prudent management the business prospered, and her husband was not

again haunted by fear of ruin. James was her youngest child, and in the

weary weeks of sickness preceding her death, which took place when he

was about nine years old, was often with her while the older members of

the family were busy in the bake-house or the shop. To the latest hour

of life he retained the memory of her appearance as she sat reading her

Bible, or as she knelt in frequent prayer; and there was always a deep,

sweet melody for him in the metrical version of the twentieth psalm,

“Mother’s Psalm,” as it was called, on account of her repetition of it

in every dark and trying hour. When about four years old, James was sent

to a school kept by a man who, having lost a limb, was popularly known

as “Timmerleg.” He soon acquired all the learning “Timmerleg” could

impart, and was removed to the parish school, where he remained nntil he

began his college course. In boyhood, as in manhood, he was bright and

blithe, and an old woman described him as “a rosy bairn, wi’ laughin’

mou’ and dimpled cheeks.” His brothers spoke of him as “the wise wean,”

and “the young philosopher,” and proudly anticipated the day when his

name would be acknowledged as one of the glories of his native land.

Their earnings were put into a common purse, and freely bestowed on his

education. But though he knew he was to be the gentleman of the family,

he was, in his school-days, a cheerful helper of his father and brothers

in their trade. His brother Alexander wrote of him, “James was ever so

loving, gentle, and obliging, that though I, like most hard workers in a

warm atmosphere, was rather quick of temper, I do not recollect ever to

have been angry with him. He was aye at the call of the older members of

the house, running with rolls to Balbardie House, where, as ‘the bonnie

callant’ he was a great favourite; or ready to keep the shop for a time,

when he always had a book in his hand.” Alexander watched over him with

affectionate tenderness, and in warning him against the temptations to

looseness of life which prevailed in the town, would put his arm round

his neck, and say, “Others may do this, but it would break a' our

hearts, and blast a’ your prospects were you to do it.” One night when

he had been out later than usual, and had been spoken to in that manner,

he “was greatly troubled, and cried a’ the night like to break his

heart.”

It was well for him that he had such warnings ringing in his ears, when

at the age of fourteen he left the homely scenes of Bathgate for the

excitements of college life in Edinburgh. He was kept from vice and

indolence by the thought of the anguish which any blemish in his

character would cause to the loving hearts at home. Notwithstanding the

generosity of his father and brothers in supplying him with means for

his university training, he was economical in his expenditure, only

varying his plain diet with the occasional luxury of four pennyworth of

fruit. To make the cost still lighter to them he competed for, and won a

bursary of the yearly value of £10, which he held for three years. In

classics, mathematics, and moral philosophy, he scarcely rose above

mediocrity, but excelled in medical studies. He officiated as surgeon’s

dresser in the Royal Infirmary, and was so affected by the terrible

agony of a Highland woman while undergoing an operation, that he decided

to give up all thought of a profession in which he would have to witness

so much suffering, and went to the Parliament House to seek employment

as clerk to a writer. Happily, the right instinct prevailed, and he

returned to the study of medicine, asking a question, which he was

afterwards able to answer in the affirmative in a masterly and practical

manner, “Can anything be done to make operations less painful?”

In the fifth year of his

university course, his father was stricken by fatal sickness, and he

attended him with unwearying affection to the day of his death. He was

at that time about to pass the examination for surgeon’s degree, but his

reading having been interrupted, he was apprehensive of failure, and was

disposed to wait another year. Encouraged, however, by his good brother

Alexander, he went forward, passed with ease and credit, and was

instituted a member of the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh, before

he was nineteen years old. Being too young to take his degree as Doctor

of Medicine, he returned to Bathgate, and spent his time, partly in

wandering over the hills in search of stones and plants, and partly in

assisting a local practitioner, who in later years pointed with pride to

the labels on his bottles as having been written by the famous

physician. But he wished for work, and was a candidate for the situation

of surgeon in a small village on the Clyde. The decision of the village

folk was against him, and many years after he said, “ When not selected,

I felt, perhaps, a deeper amount of disappointment and chagrin than I

have ever experienced since that date. If chosen, I would probably have

been working there as a village doctor still.” The gratification of his

wish might have been a calamity to himself and to the world, and he

gratefully confessed the goodness of God in the frustration of his

youthful ambition. Still receiving pecuniary aid from his brothers, he

resumed his studies in Edinburgh, and took his medical diploma in 1833.

An eminent physician

engaged him as his assistant, and at the beginning of his practice, as

well as in his more brilliant days, he endeavoured to work out his own

ideal of professional activity: “To give as humble agents under a Higher

Power, ease to the agonised, rest to the sleepless, strength to the

weak, health to the sick, and sometimes life to the dying; to distribute

everywhere freely a knowledge of those means that are fitted to defend

our fellow-man against the assault of disease, and to quench within him

the consuming fire of sickness.” In 1835, Dr. Simpson visited London and

Paris. He was not without the poetic sensibilities which are excited by

beautiful scenery and works of art. The landscapes of England and France

were rich and lovely to his eyes, and he wandered with delight through

gorgeous cathedrals, and galleries luminous with the pictures of the

great masters. But the principal object of his tour was to ascertain the

management of patients in different hospitals, to inspect anatomical

museums and schools of medicine, and to obtain personal knowledge of the

men who were at that time most eminent in the various branches of

medical science.

Returning to Edinburgh with his note-book and his memory full of

newly-acquired facts, he was elected, though still a young man, Senior

President of the Royal Medical Society, and found scope for all his

powers in private practice, in professional dissertations, and in

lectures to medical students. He married Miss Jessie Grindlay, of

Liverpool, in December, 1839, but there was no honeymoon, for at that

time he was engaged in an eager canvass for a vacant chair in the

medical department of the University. The appointment was with the Town

Council, and each of the candidates competed to the utmost for the

favour of its members. Testimonials were accumulated, friends were

solicited for their influence, and so spirited was the contest that Dr.

Simpson spent £500 in printing and postage. Formidable interests were

set in array against the baker’s son, but the council acknowledged his

fitness for the office, and he was able to write to his mother-in-law,

“Jessie’s honeymoon and mine is to begin to-morrow. I was elected

Professor to-day by a MAJORITY OF ONE. Hurrah!!!” He received many

congratulations on his appointment, but the one he valued most was from

his sister Mary, who had been as a mother to him in his boyhood, and who

at the time of the election, was with her husband on board a ship in the

channel, about to sail for Australia. “My dear, dear, and fortunate

brother, I have taken up my pen to wish you joy, joy; but I feel I am

scarcely able to write. I never believed till now, ti^at excess of joy

was worse to bear than excess of grief. I cannot describe how, but I

certainly feel as I never did all my life. I hope we will be here

to-morrow to learn all the particulars of this happy event. My dear,

dear James, may God Himself bless you, and prosper you in all your

ways.”

Dr. Simpson’s lectures

drew many students to the class-room, and the first year his fees

amounted to £600. His private practice also increased with his

increasing renown, and aristocratic families began to seek his advice.

For a number of years he had struggled with pecuniary embarassments, but

at length his income exceeded his expenditure, and he was able to repay

the amounts which had been advanced to him by members of his family.

Though an enthusiast in all that related to his own science, he was at

the same time passionately addicted to archeological and other kindred

pursuits. When be could snatch an hour from professional duties, it was

devoted to the examination of ancient buildings and monumental stones,

or to researches in antiquarian literature. His attention at one time

was directed to the ancient Leper Houses in England and Scotland, and by

consulting old registers, and monastic and municipal chronicles, traced

the history of one hundred and nineteen hospitals founded for lepers. To

those who have only thought of leprosy as an oriental disease, it is

startling to find that in past centuries it was so prevalent in Britain.

We may well be thankful to God that no Lazar-House is now needed in any

part of the country, and that the sad cry, “Unclean, unclean,” is not

heard in any of our streets. Dr. Simpson was also deeply interested in

relics of the prehistoric inhabitants of the land; and friends and

grateful patients often gratified him by sending accounts of graven

rocks, or by augmenting his store of “auld nick-nackets,” with fragments

of antique pottery, flint spear-heads, and rude ornaments for the person

found in caves or turned up by the plough. He wrote and published works

on Archaeology as well, as on surgery and medicine, and, considering his

many engagements, evinced astonishing thoroughness and acquaintance with

detail in all his books. As a writer, he had not the graphic lines, the

gleams of sunny splendour, and touches of gorgeous colour, which came so

freely from the pen of Hugh Miller; nor had he the brilliant

imaginativeness which enabled Greorge Wilson and David Brewster to throw

into scientific disquisition, the glow and enchantment of poetry, but he

set his facts and theories in clear light, and gave a charm to them by

grouping about them abundance of historical and biographical references.

In 1847, Dr. Simpson said, “I can think of naught else.” This was in

allusion to the use of sulphuric ether for the purpose of inducing

unconsciousness in surgical operations, and in the line of practice to

which he was specially devoted. Confident “that the proud mission of the

physician is distinctly twofold, namely, to alleviate human suffering as

well as to preserve human life,” he was thankful beyond measure to see

how, under the influence of ether, the patient, who otherwise would have

been frenzied with pain, calmly slept while the surgeon was amputating a

limb or removing an excrescence. But he saw some objections to ether,

and experimented on himself with other volatile fluids, in the hope of

finding one that would be thoroughly efficacious, and at the same time

free from all injurious effects. The anaesthetic properties of

chloroform were discovered by him almost accidentally. Some of the

liquid, which had its origin in French chemistry, had been beside him

for several days. “ But,” he said, “ it seemed so unlikely a liquid to

produce results of any kind, that it was laid aside, and on searching

for another object among some loose paper, after coming home late one

night, my hand chanced to fall upon it, and I poured some of the fluid

into tumblers before my assistants, Dr. Keith and Dr. Duncan, and

myself. Before sitting down to supper, we all inhaled the fluid, and

were all ‘under the mahogany’ in a trice, to my wife’s consternation and

alarm. In pursuing the inquiry, perhaps thus rashly begun, I became

every day more and more convinced of the superior anaesthetic effects of

chloroform as compared with ether.” Chloroform was soon in extensive use

both in surgery and obstetric practice, and Dr. Simpson was eulogised by

many as a philanthropic discoverer, but there were some, who, on

religious grounds, objected to the triumph over pain which had been won

by the new anaesthetic. In replying to them he adduced the fact that

Christ has removed the curse under which man had fallen, and that the

Gospel not only gives assurance of salvation for the sonl, but also by

its general spirit and tendency, encourages all attempts to alleviate

the sufferings of the body. He also quoted in illustration and support

of his principle, Genesis ii. 21, “And the Lord God caused a deep sleep

to fall upon Adam, and he slept, and he took one of his ribs, and closed

up the flesh instead thereof.” Though satisfied with chloroform, the

professor went on trying the effect of other fluids by personal

inhalation of their vapours. One day his butler found him in his room in

a state of unconsciousness, and said, “He’ll kill himsel’ yet wi’ thae

experiments; and he’s a big fule, for they’ll never find onything better

nor chlory.” Chloroform was in such demand that it was even kept in

village shops, and Dr. Simpson was able to attest that in one place at

least its sale was guarded with praiseworthy care. He was on an

antiquarian excursion, and was accompanied by his youngest son, who had

a sudden attack of toothache. Going into a druggist’s shop he asked for

a little chloroform, but the lady who had charge of the drugs, said,

“Na, na; we dinna sell chloroform to folk that kens naething about it.”

Dr. Simpson was spoken of by one who knew him as realising the ideal of

a perfect Esculapius, having the brain of an Apollo, the heart of a

lion, the eye of an eagle, and the hand of a lady. As his quick judgment

and amazing skill became more widely known, Iris services were in such

request, and it was thought such a favour to obtain them, that his

position in Edinburgh was more like that of a prince than a medical man.

His reception rooms were crowded with patients; letters and telegrams

were forwarded to him in swift succession, imploring his help, and many

noble families were proud and thankful to have him as their physician.

Nor was his reputation limited to the British Isles, for people came to

consult him from almost all parts of the world, and a host of strangers

visited Edinburgh, not to tread the stately gallery of Holyrood, or to

see the regalia of the Scottish kings in the castle, but with the hope

of receiving benefit from the famous doctor. He was one of the great

notabilities of the city; and with a head resembling that of Professor

John Wilson, and a countenance expressing intellectual power, yet

beaming with kindly feeling, was looked upon as an embodiment of medical

genius, and as a benefactor of mankind. Wealth flowed in upon him: he

received as much as £300 in one fee, and his professional income was

estimated as being not less than £10,000 a year.

But magnificently

conspicuous as he was among the medical brotherhood, it was not until

1861 that he sought and obtained that which was needed as the perfecting

crown of his gifts and honours— the grace of God. It does not appear

that at any time of his life he was inclined to scepticism, or that he

was in captivity to any of the grosser forms of dissipation. He was so

far in sympathy with the evangelical ministers of Scotland that after

the Disruption he became a member of the Free Church, but he had no

experience of religion as a joy for his inner life; for though when

under the pressure of domestic sorrow or professional troubles he felt

the need of Divine support, he did not throw himself in simple faith on

the atonement of Christ. He held the Gospel more as a venerable relic of

the past than as a vitality more pervasive than that which makes the

tree laugh with all its leaves in response to the voice of Spring. But

in 1861 he yielded to a number of godly influences that were pressing

upon him, and submitting himself to the Scriptural method of salvation,

could say on the Christmas Day of that year, “My first happy Christmas;

my only one.” His joy was great, and it was heightened by conversions in

his family. To a friend he wrote: “Of late the love of God to me and

mine has been perfectly transcendent. Christ seems to have taken one and

all of my family to Himself for the children of His kingdom. . . . The

world seems quite, quite changed; ‘All old things now are passed away.’

”Family prayer was conducted not simply as a decent ceremony, but as a

service abounding in sacred pleasure. Strangers felt themselves to be on

holy ground when the hymn was sung by the children and the servants, and

the Doctor read a chapter in the Bible, and then sought the blessing of

God on the various pursuits of the day. He was not only intent on doing

good to those of his own household, but had tender and gracious words

for many of his patients, and also took part in evangelical meetings.

To a company of medical

students convened by request of the Committee of the Medical Missionary

Society, he said: “I feel as if it were scarcely fitting that I should

stand up to speak upon the subject on which I am expected to address

you,— I, who am one of the oldest sinners and one of the youngest

believers in the room. When I got a note requesting me to do so, I was

in a sick-bed, ill of fever, and I at once said, ‘I cannot do this.’ But

when I came to reflect further, I felt I must do it. I cannot speak

earnestly, or as I ought for Jesus, but let me try to speak a little of

Him—His matchless love, His great redemption which He offers to you and

me.” The doctrines of the Gospel were presented in a forceful manner,

and with professional allusions which would be thoroughly appreciated by

the audience, and the address was concluded with the following

exhortation: “ Many kind friends are trying to awaken you to the

momentous importance of these things, and calling upon you to believe in

Christ. If any of these, or anything you have heard here, has stirred

you up, do not, I beseech you, put aside your anxiety. Follow it up;

follow it out. If in your own lodgings, in the dark watches of the

night, you are troubled with a thought about your soul—if you hear some

one knocking at your heart—listen. It is He Who said, 1800 years ago

upon the sea of Galilee, ‘It is I; be not afraid.’ Open the door of your

heart. Say to Him, Come in. In Christ you will find a Saviour, a

companion, a counsellor, a friend, a brother, who loves you with a love

greater than human heart can conceive.”

In 1866 Dr. Simpson received a letter from Lord John Russell, informing

him that he had received Her Majesty’s command to offer him a baronetcy,

as a recognition of his professional merits, and with special reference

to his application of chloroform in surgical practice. The death of a

son of great promise caused him to hesitate in accepting the offer, but

the arguments of his friends prevailed, and with some violence to his

own feelings he was invested with the honour. When it was known that he

had received the patent, many letters of congratulation were sent to

him, and the Edinburgh people shook hands with him until his arm was

weary and sore. But there was no one so proud of the title as his

brother Alexander at Bathgate. It was to him gratifying beyond

expression that the Jamie who had carried out hot rolls and waited in

the baker’s shop had been raised to the rank of a baronet of the United

Kingdom. Sir James Simpson did not long enjoy the distinction awarded to

him. His strength was broken by excessive labours, and he died on May

6th, 1870. In his last sickness he said, “ I have not lived so near to

Christ as I desired to do. I have had a busy life, but have not given so

much time to eternal things as I should have sought. Yet I know it is

not my merit I am to trust to for eternal life. Christ is all. The hymn

expresses my thought—

"Just as I am, without one

plea,

But that Thy blood was shed for me.*

I so like that hymn. The

words “Jesus only” were frequently repeated by him; and in hope and

thankfulness he passed away, in the fifty-ninth year of his age. There

was a proposal to give him a tomb in Westminster Abbey, but his family,

having regard to his own wish, buried him in Warriston Cemetery. His

funeral was magnificent in the numbers who attended it, and the tears of

the poor showed how generously he had befriended them. Glowing

testimonies were given to his genius as a physician, and his nobleness

as a Christian, among which were the following verses from one of his

fellow-workers:

“Great in his art and

peerless in resource,

He strove the fiend of human pain to quell;

Nor ever champion dared so bold a course

With truer art, or weapons proved so well.

"Yet greater was he in his own great soul,

A brimful fount of pity, warm and pure,—

Which, as the quiv’ring needle for its pole,

Panted to soothe the pains it could not cure.

“On such emprise his ardent heart was bent

While, walking by faith’s holy light, he trod

The Shepherd’s path, with tears and blood besprent,

Which leads the flock up to the hills of God!” |