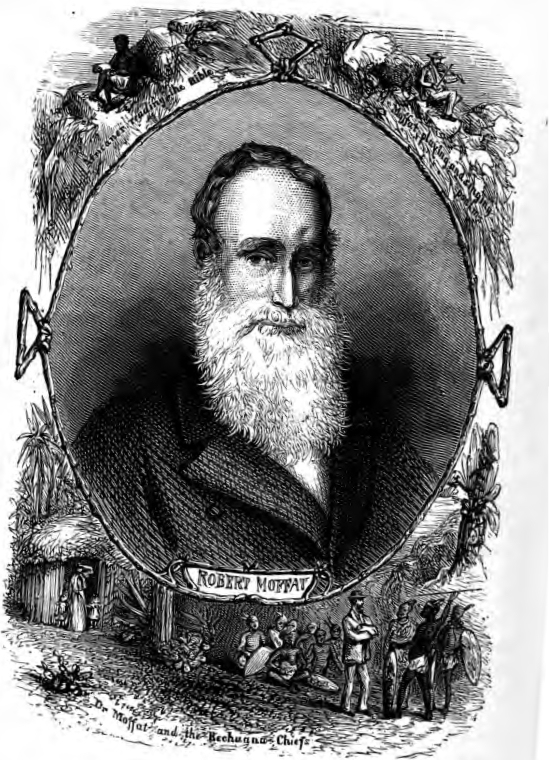

ROBERT MOFFAT, “the

Patriarch of Kuruman,” was born at Ormestone, near Haddington, in 1795,

but spent the greater part of his boyhood at Carron Shore, where his

father had an appointment in the Customs. When about twelve years old,

he was ambitions to be a sailor, and tried a voyage in a coasting

vessel. Not finding much that was pleasant in sea-faring life, he

returned to school, and began to study botany and horticulture, in order

to qualify himself for the position of a skilled gardener. His father

removing to Inverkeithing, in Fifeshire, he obtained employment near

that town, in the gardens of the Earl of Moray. While nailing the twigs

of the apricot to the wall, or planting the ferns on the rockery, he had

no thought of Africa as the scene of various and incessant labours to be

perpetuated through many years. But God had a glorious work for him to

do on that continent* and by His providence drew him along the path to

the kraal of Africaner and the fountain of Kuruman. Scotch gardeners

then, as now, had a good repute in England, and he was offered a

situation in Cheshire. On leaving. home his mother wished him to promise

that he would read his Bible every day, both morning and evening. He

tried to evade her request, but as she was about to bid him farewell,

she took his hand and, looking into his face with tearful eyes, said,

“Robert, you will promise me to read the Bible, more particularly the

New Testament, and most especially the Gospels—these are the words of

Christ Himself; and there yon cannot possibly go astray.” He could not

resist such an appeal, and replied, “Yes, Mother, I make you the

promise.” Having made it, he kept it, and always thought himself happy

in having done so. He was converted in England, and occasionally went to

a Methodist service at a farm-house in the Warrington Circuit when the

Rev. J. Beaumont was one of its ministers. A slight circumstance

directed his attention to the Mission field. Being in Warrington one

summer’s evening, he caught site of a placard, two lines of which

arrested his attention—“The London Missionary Socieiy” and “The Rev. W.

Roby, of Manchester.” The meeting announced on the placard had been

held, but he resolved on seeing Mr. Roby and offering himself for

Mission work. Mr. Roby received him with great kindness, told him to be

of good courage, and promised to use what influence he had with the

directors of the Society on his behalf.

He was accepted by the Society, and ordained with some other young men

as a minister of the Gospel to the heathen in Surrey Chapel. One of the

young men who knelt by his side to receive the imposition of hands was

John Williams, who, though slain by the savages of Erromanga, has a name

in the annals of Missionary toil and heroism bright as the stars which

pour their lustre on the palms of the Polynesian archipelagoes. Mr.

Moffat sailed for the Cape of Good Hope in October, 1816. He was only

about twenty-one years old, but had sufficient Scotch prudence and

determination to avoid blunders and to front difficulties in a manful

spirit. When he reached the Cape he had to solicit the permission of the

British Governor to visit the heathen beyond the boundaries of the

colony. This was refused for some time; but the young Missionary while

waiting was not idle. Lodging with a godly Hollander, he acquired the

Dutch language, so as to be able to preach to the Dutch Boers and their

native servants. Repeated applications to the Governor were at length

successful, and in going up the country he asked one of the Boers to

allow him to spend the night at his house. The Boer blustered as much as

if the traveller had petitioned him for the gift of a hundred oxen, and

Mr. Moffat thought to himself, “I’ll e’en try the guid wife.” She not

only provided food for him, but also asked him to preach. The service

was held in a long bam, and though the Boer had a hundred Hottentots in

his service, not one of them was present. “May none of your Servants

come in?” asked the Missionary. “Hottentots!” shouted the Boer, in

reply; “are you come to preach to Hottentots? Go to the mountains and

preach to the baboons; or if you like, I’ll fetch my dogs, and you may

preach to them.” Those contemptuous words were followed by the

appropriate text, “Truth, Lord; yet the dogs eat of the crumbs which

fall from their master’s table.” The truth smote the heart of the Boer,

and he cried out, “No more of that; I’ll bring you all the Hottentots in

the place.” He at once summoned them to the bam, and at the close of the

service said to Mr. Moffat, “I’ll never object to the preaching of the

Gospel to Hottentots again.”

Mr. Moffat was on his way to Namaqua Land, beyond the Orange River,

where he was to do Mission work among the people of the terrible

Africaner. The conversion of this fiery chieftain to the meekness of

Christian discipleship is justly regarded as a signal proof of the power

of the Gospel. His father, being enfeebled by age, resigned to him the

government of a tribe of Hottentots, whose lands at one time reached

within a hundred miles of Cape Town, and whose kraals and pastures and

hunting-grounds were scenes of rude abundance and barbaric freedom. But

the Dutch settlers gradually encroached on their possessions, and

Africaner, deprived of the old inheritance of his family, was induced to

accept service as shepherd to a Dutch farmer. Generous treatment would

have tended to reconcile him to the unfortunate change in his position,

but his master aggravated his sense of humiliation by an overbearing,

insolent manner, and even ordered him to take up arms against his own

people. The order was not obeyed, and Africaner, with his brother Titus

and some others, was summoned to the farm-house to be reprimanded, if

not punished, for disobedience. Africaner went up the steps to the door

for the purpose of remonstrating with the farmer, who, instead of

listening to him, gave him a sudden blow, which hurled him to the bottom

of the steps. This was too much for the patience of Titus, who, having a

gun, fired at and killed the farmer. To escape the vengeance of the

Dutch for that deed of blood the party hastened to the north of the

Orange River, and settled in Great Namaqua Land.

Many and fierce attempts

were made by the colonial authorities to destroy Africaner, but they

only excited him to deadly reprisals, and he became the terror of all

the farmsteads in the border country. It was to the kraal of this

dreaded outlaw that Mr. Moffat was travelling. The farmers at whose

houses he was entertained assured him that Africaner would think no more

of taking his life than he would of taking the life of a zebra or an

antelope. One told him that the chief would strip off his skin and make

a drum of it; another that he would strike his head from his body, and

use his skull for a drinking cup; and a motherly old lady, wiping the

tears from her eyes, said to him, “Had you been an old man it would have

been nothing, for you would soon have died, whether or no; but you are

young, and going to be eaten up by that monster!” Africaner was not so

bad as he had been pictured by the fears of the planters. Missionaries

had given him instruction in the doctrines of Christianity, and he had

been baptised, though it can scarcely be said that his heart had been

affected by Divine grace. Mr. Moffat was in no danger of being martyred

by him; but found little that was encouraging in his position when,

having crossed the Orange River, he entered the scene of his labours in

Namaqua Land. He was in a rocky, arid country, presenting a sad contrast

to the bright gardens at Inverkeithing and the embowered lanes and

grassy slopes of Cheshire. Africaner was slow in giving him a welcome;

but at length came to him, and seemed pleased when he ascertained that

the London Missionary Socieiy had sent him to the station. He directed a

number of women to make a house for him, which they did by bending long

rods into a hemispheric form, and covering them with mats. It was as

uncomfortable as it was frail, for the rain streamed through it, the suU

heated it to an almost unbearable degree, and when the wind blew it was

filled with suffocating dust. Vagrant dogs crept into it for a night’s

shelter, and frequently ran off with the food the Missionary had

prepared for the following day; serpents coiled themselves behind his

boxes; and at times he had to start up from sleep to drive away

contending bulls, lest in their struggles they should crush himself and

his dwelling. Through the day he was fully employed in teaching school

and holding services, and in the evening he wandered to a pile of rocks

in the neighbourhood, where he poured out his soul in alternate strains

of joy and sorrow; and occasionally reclining on one of the slabs of

granite, would break the stillness with the notes of his violin, and

sing his mother’s favourite hymn, beginning—

“Awake my soul, in joyful

lays,

To sing the great Redeemer’s praise.”

He was soon cheered by a

pleasing change in Africaner. Ho one at the kraal was more regular in

attending the public services: the truth accompanied by the Holy Spirit

was apprehended by him as a transforming energy, and the fierceness of

the bandit was melted into the gentleness of the Christian. The weapons

by which he had become so formidable were laid aside, and the Bible was

almost always in his hands. “Often have I seen him,” says the

Missionary, “under the shadow of a great rock, nearly the livelong day,

eagerly perusing the pages of Divine inspiration; or in his hut he would

sit, unconscious of the affairs of a family around, or the entrance of a

stranger, with his eye gazing on the blessed Book, and his mind wrapped

up in things divine. Many were the nights he sat with me on a great

stone at the door of my habitation, conversing with me till the dawn of

another day, on creation, providence, redemption, and the glories of the

heavenly world.”

Africaner’s visit to Cape Town with Mr. Moffat, excited great interest

in that part of Africa. When the visit was first proposed to him, he

said to the Missionary, “I had thought you loved me, and do you advise

me to go to the government to be hung up as a spectacle of public

justice?” then laying his hand on his head he asked, “Do you not know

that I am an outlaw, and that one thousand rix-dollars have been offered

for this poor head?” Mr. Moffat having assured him that he would be well

received in Cape Town, and that in all respects the journey would be

satisfactory, he agreed to go. On their way they came near a farm-house

in which Mr. Moffat had received kind entertainment when travelling

towards Namaqua Land. Mr. Moffat left the waggon and went alone to meet

the farmer. The latter seemed startled by his appearance, and asked in

rather a wild manner who he was. When the name was given the farmer

exclaimed, “Moffat! it is your ghost!” and it was with difficulty he was

persuaded that it was the living Missionary; for the general report was

that he had been murdered by Africaner, and one man declared that he had

seen his bones. Walking towards the waggon, they were speaking of

Africaner, and Mr. Moffat said, “He is now a truly good man.” To this

the farmer replied, “I can believe almost anything you say, but that I

cannot credit. There are seven wonders in the world; that would be the

eighth.” The Missionary appealed to numerous triumphs of divine grace in

the conversion of great sinners, in proof that it was not impossible for

the Hottentot chieftain to have been converted; but the farmer was still

doubtful, for he looked on Africaner as one of the accursed sons of Ham

to whom it was in vain to preach the Gospel, and ended the conversation

by saying, “ Well, if what you assert be true respecting that man, I

have only one wish, and that is to see him before I die ; and when you

return, as sure as the sun is over our heads, I will go with you to see

him, though he killed my uncle.”

They were then near the

chief, and Mr. Moffat confiding in the goodness and prudence of the

farmer said, “This, then, is Africaner.” A few questions having been

satisfactorily answered by Africaner, the farmer raised his eyes to

heaven and exclaimed, “O God, what a miracle of Thy power! What cannot

Thy grace accomplish!” Africaner was kindly and affably received in Cape

Town by the Governor of the Colony, Lord Charles Somerset, and many in

the town, who had heard of his terrible exploits years before, were

filled with astonishment as they witnessed his meek deportment, and

discovered his thorough acquaintance with, and delight in the Word of

God. He was faithful to the close of life, and the following description

of his death was given by a Wesleyan Missionary: “When he found his end

approaching, he called all the people together after the example of

Joshua, and gave them directions as to their future conduct. ‘We are

not,* he said, ‘what we were, savages, but men professing to be taught

according to the Gospel. Let us tfien do accordingly. Live peaceably

with all men, if possible; and if impossible, consult those who are

placed over yon, before you engage in anything. Remain together as you

have done since I knew you. Then, when the Directors think fit to send

you a Missionary, you may be ready to receive him. Behave to any teacher

you may have sent, as one sent of God, as I have great hope that God

will bless you in this respect when I am gone to heaven. I feel that I

love God and that He has done much for me, of which I am totally

unworthy. My former life is stained with blood; but Jesus Christ has

pardoned me, and I am going to heaven. Oh! beware of falling into the

same evils in which I have led you frequently ; but seek God, and He

will be found of you to direct you/ ” So died the man whose black hands

had often been red with the blood of Dutch Boers, and whose black face

lifted in savage triumph had often been brightened in the glare of

blazing farmsteads. The great Missionary who guided him to the cross of

Christ will have a crown jewelled with many resplendent memorials of

noble and heroic service done in the cause of the Divine Master, but

none will shine more conspicuously than that on which the name of

Africaner will be graven.

While in Cape Town Mr. Moffat was married to Miss Smith, who had gone

out to him from England. She cheered the loneliness of an African

mission station by her bright and genial presence, and encouraged her

husband in his work by a hopefulness that rarely failed, even in the

darkest days of trial and disappointment. Though strongly attached to

Africaner and his people, Mr. Moffat did not go back to Namaqua Land,

for a deputation from the London Missionary Society being at the Cape at

the time of his marriage wished him to prosecute a Mission among the

Bechuanas. After a short stay at Griqua Town, he and Mrs. Moffat went to

the Kuruman where Mr. Hamilton had formed a station. Their patience was

severely tested by the selfishness and perversity of the natives. The

Missionaries dug a ditch some miles in length, in order to obtain a

supply of water from the Kuruman for their gardens, which were on a

light sandy soil, and would grow little without irrigation. The women of

the village seeing the fertilising effect of the water on the mission

gardens, wished to have the same advantage for their own, and so opened

the ditch as to have a flood on their grounds, while the Missionaries

had not a drop of water for domestic purposes, and had the mortification

of seeing their vegetables wither and die away for want of moisture.

When they remonstrated,

the women, forgetful of their own interest, but ready to do anything to

annoy their white benefactors, broke down the dam by which the water had

been diverted from the river to the ditch. Thefts from the mission

premises were frequent. Tools were taken away, and after being

completely spoiled, were impudently brought back and offered in barter

for valuable articles. Cattle were let out of the fold, and driven into

bogs where only hyenas or natives could get at them, and if the

Missionaries bought a small flock of sheep they were thankful if they

secured half of them for their own use. Men and women crowded into Mr.

Moffat’s house, poisoning the atmosphere with the stench of their

bodies, not leaving room for Mrs. Moffat to attend to her household

duties, and defiling everything they touched with their greasy attire.

At the public services there would often be an indecorum that was

painful to witness. Some of the people would be snoring, others

laughing, others disgustingly busy with their fingers, and sadly

endangering the comfort and cleanliness of the Missionary’s wife, when

sitting close beside her.

The trials of the little

band of Christian pioneers were increased by a long drought, for which

they were blamed and cursed. It was said that their chapel-beU

frightened away the clouds; and even Mr. Moffat’s black beard and a bag

of salt he had brought in his waggon from Griqua Town, were imagined to

have something to do with the unkindliness of the heavens. The feeling

became so strong against the Missionaries that they were informed they

would be driven out of the country, if they did not speedily take

themselves away. A formidable deputation gathered in the shadow of a

large tree near Mr. Moffat’s house; and while Mrs. Moffat stood at the

door with a babe in her arms watching the crisis, a chief, quivering a

spear in his right hand in an imposing manner, delivered the decision

which had been arrived at in a secret council. Mr. Moffat boldly

replied: “We have indeed felt most reluctant to leave, and are now more

than ever resolved to abide by our post. We pity you, for you know not

what you do: we have suffered it is true, and He Whose servants we are

has directed us in His Word, ‘When they persecute you in one city, flee

ye to another ;’ but although we have suffered, we do not consider all

that has been done to us by the people amounts to persecution; we are

prepared to expect it from such as know no better. If you are resolved

to rid yourselves of us, you must resort to stronger measures, for our

hearts are with you. You may shed blood or burn us out. We know you will

not touch our wives and children. Then shall they who sent us know, and

God Who now sees and hears what we do, shall know that we have been

persecuted indeed.” Even Bechuana savages were touched by the brave

spirit of the Missionary, and they said: “ These men must have ten

lives, when they are so fearless of death; there must be something in

immortality.” No further attempt was made to molest the Missionaries,

and Mr. Moffat had soon an opportunity of rendering services to the

tribe by which he gained their confidence and esteem.

For more than a year

there had been a strange talk in the settlement about a woman named

Mantatee, who was said to be advancing with a mighty army from the

interior, conquering all before her, and leaving desolation in her

footsteps. Mr. Moffat did not give much credit to the rumour, but being

up the country on a mission to a powerful chief who lived about two

hundred miles from the Kuruman, was convinced that there was truth in

the story of the Mantatee army, and saw that unless vigorous measures

were adopted it would not be long before his own station would be

overrun by the mysterious and insatiable warriors. He hastened home, and

communicated the alarming tidings to the people, who were in such

consternation that some of them proposed immediate flight to the

Kalahari Desert. But Mr. Moffat knew that though the Mantatees would not

follow them to those arid regions, they would perish from hunger and

thirst, and suggested as a wiser plan, a request to the Griquas for

help. The suggestion was agreed to, and Mr. Moffat went in his waggon to

Griqua Town, where he succeeded in his purpose with the chief Waterboer.

Repeated attempts were made to parley with the Mantatees, but they only

became fiercer in their warlike demonstrations, and the Griquas having

united with the Bechuanas so completely routed them that they fled from

the country. There were occasional tidings of their re-appearance which

caused great excitement at the mission station, but whatever lands they

ravaged they did not again march towards the Kuruman. After the

deliverance of the Bechuanas from the dreaded invaders, they manifested

a kindlier spirit to the Missionaries, and consented to their removal to

a site nearer the source of the river, where they had a much better

supply of water. Before the new station was completed,

Mr. Moffat went on a

visit to Makaba, king of the Bauangketsi. The king great in war and

conquest was delighted to see him, and honoured him highly in his own

rude way. Sitting by his side one day when be was surrounded by his

nobles and counsellors, Mr. Moffat began to speak of the Saviour’s

mission to the world. Makaba was at first indifferent, but when be beard

of the resurrection of the dead wad startled. He asked if his own father

would rise, if the dead slain in battle would rise, and if those who bad

been killed by lions, tigers, hyenas, and crocodiles would rise. On

being assured that they would, be turned to his people and asked in a

stentorian voice, “Hark, ye wise men, whoever is among you, the wisest

of past generations, did ever your ears bear such strange and unheard-of

news?” Then, addressing the Missionary, he said: “Father, I love you

much. Your visit and your presence have made my heart white as milk. The

words of your mouth are sweet as honey, but the words of a resurrection

are too great to be beard. I do not wish to bear again about tbe dead

rising! The dead cannot arise! The dead must not arise!” “Why,” rejoined

Mr. Moffat, “can so great a man refuse knowledge, and turn away from

wisdom? Tell me, my friend, why I may not speak of a resurrection?”

The king, raising and

uncovering his arm, and shaking his hand as if quivering a spear, said,

“I have slain my thousands, and shall they arise?” His conscience had

not been troubled by the slaughter of those he bad overcome in battle,

but he was appalled as be thought of them starting up from their sleep

on the rocks and under the long grass, and confronting him with vengeful

eyes and upbraiding lips. While Mr. Moffat was away from home, his wife

was alarmed by tidings that he had fallen into the bands of the

Mantatees, and that portions of his clothes had been seen stained with

blood. He was in danger; but the Providence of God was over him, and he

bad the pleasure of uniting with his family in expressions of

thankfulness for the guidance and defence of the Divine band.

The Missionaries worked hard at the new station; but it was not until

the year 1828 that they were able to rejoice in extensive success. Then

a new life seemed to permeate the people, and Mr. Moffat wrote: “Sable

cheeks bedewed with tears attracted our observation. To see females weep

was nothing extraordinary; it was, according to Bechuana notions, their

province and theirs alone. Men would not weep. After having, by the rite

of circumcision, become men, they scorned to shed a tear. In family or

national afflictions it was the woman’s work to weep and wail; the man’s

to sit in sullen silence, often brooding deeds of revenge and death. The

simple Gospel now melted their flinty hearts; and eyes now wept which

never before shed the tear of hallowed sorrow. Notwithstanding our

earnest desires and fervent prayers, we were taken by surprise. We had

so long been accustomed to indifference that we felt unprepared to look

on a scene which perfectly overwhelmed our minds. Our temporary little

chapel became a Bochim—a place of weeping, and the sympathy of feeling

spread from heart to heart, so that even infants wept.” The people were

so anxious to obtain mercy that numbers of them held meetings in their

own huts, and singing and praying was heard from one end of the village

to the other. Native assistance was volunteered in the erection of a

school-house, which was to serve as a chapel until a more suitable one

could be provided. When it was opened for worship it was crowded, and

the day was made memorable by the baptism of several inquirers, and by

gracious tokens of the presence of God. Conversion was followed by

social improvement. Disgusting habits induced by heathenism were

abandoned; the men became more industrious, the women learned to sew,

and instead of wearing greasy skins, clothed themselves in clean and

decent garments; and huts, in which previously there had not been a sign

of domestic comfort, were furnished with chairs and tables. As the

Missionaries saw the change which had been effected, they could not but

feel that they had before them an additional proof of the truth of the

words, “They that sow in tears shall reap in joy. He that goeth forth

and weepeth, bearing precious seed, shall doubtless come again with

rejoicing, bringing his sheaves with him.”

The foundations of a chapel were laid in 1830, but partly owing to the

difficulty in procuring timber the building was not completed until

1839. At that date Kuruman was like an Eden in the wilderness. Lofty

trees of the willow species bordered the watercourses by which the

gardens were kept in freshness and luxuriance. Beyond the gardens, and

in a line with them, were the chapel, the school-houses, and the homes

of the Missionaries, pleasant to look upon with their walls of dove-coloured

limestone and roofs thatched with reeds and straw. The native huts, very

different to what they were before the people yielded to the influences

of religion, were scattered over the landscape, which has for background

a range of hills, broken at one point into a sharp and elevated peak.

Happily the station still flourishes, and attests by all its features of

^beauty the faith and perseverance of those who in days of sorrow and

darkness sketched its first lines, and threw upon it the transfiguring

light of the Gospel. Mr. Moffat felt that a native literature was

needed, and prepared and printed catechisms, spelling-books, and

hymn-books in Sechuana, the language of the Bechuanas. He also

translated the New Testament into the same language, and brought it to

England to have it printed under the auspices of the British and Foreign

Bible Society.

While in England he

published his graphic work, “Missionary

Labours and Scenes in South Africa,” in which there is the glow of

poetic description in combination with narratives of strange adventure,

terrible trials, and triumphs in which even angels have rejoiced. Dr.

Moffat resumed his labours at Kuruman, and, urged by Livingstone and

others, began the translation of the Old Testament. The task, which was

made to fit in with the usual toils of Missionary life, was a gigantic

one, and extended over several years. “I could hardly believe,” says Dr.

Moffat, in speaking of his feelings when the last sheet had been

written, “that I was in the world, so difficult was it for me to realise

the fact that the work of so many years was completed. Whether it was

from weakness or overstrained mental exertion I cannot tell, but a

feeling came over me as if I should die, and I felt perfectly resigned.

To overcome this I went back again to my manuscript still to be printed,

read it over and re-examined it, till at length I got back again to my

right mind. This was the most remarkable time of my life, a period that

I shall never forget My feelings found vent by my falling upon my knees

and thanking God for His grace and goodness in giving me strength to

accomplish my task.” In 1870 the veteran Missionary and his wife were

compelled by failing health to bid farewell to their beloved Kuruman,

and return to England, where they were welcomed with the enthusiasm due

to their long and faithful services. Dr. Moffat had spent more than

fifty years in Africa, and had been in perils from savage men and savage

beasts; he had known weary wanderings in the desert, when his tongue was

so parched with thirst as to be almost deprived of the power of speech;

he had visited and conciliated barbaric kings, whose halls were hung

with the trophies of cruel and exterminating war; he had confronted and

overcome difficulties in the spirit of a chivalric heroism loftier than

that which animated his ancestors on the field of Bannockburn; and he

had witnessed transformations of character and social life more

wonderful than poetry has ever imagined. Looking back from the height of

his numerous years on the scenes of protracted toil and sublime

achievement, still glowing with the Missionary ardour which in the

beginning of his course impelled him to dangers and hardships amid the

sterilities of Namaqua Land; and having before his eyes visions of

Africaner and a crowd of glorified converts from Kuruman, beckoning him

to eternal beatitude, he is worthy of the golden phrase which, in happy

parody of Milton, the Rev. W. Arthur applied to him on a great public

occasion, “That old Man Magnificent.’* |