Palaces and triumphal

arches, historic towers and lines of statuary, are not needed to make a

place famous. The builders of the Pyramids could not have done so much

to distinguish Elstow as John Bunyan has done. A Roman coliseum would

not have honoured Woolsthorpe so much as it has been honoured by the

name of Isaac Newton. Kilmany is only a country parish, yet it has more

than Arcadian charms for all who revere the memory of Thomas Chalmers.

Cromarty is but an insignificant town in the north of Scotland, yet it

is great in the annals of science and literature, as the birthplace, and

for several years the home of Hugh Miller. Many villages can boast of

architectural ornaments surpassing those of this once royal burgh, but

it is encompassed by features of natural grandeur which could not fail

to be important elements in the education of a boy of romantic and

imaginative tendencies. It stands on a strip of ground between a hill

beautifully variegated with gardens, fields, and woods; and a bay which

ere the days of maritime discovery, was regarded as one of the finest in

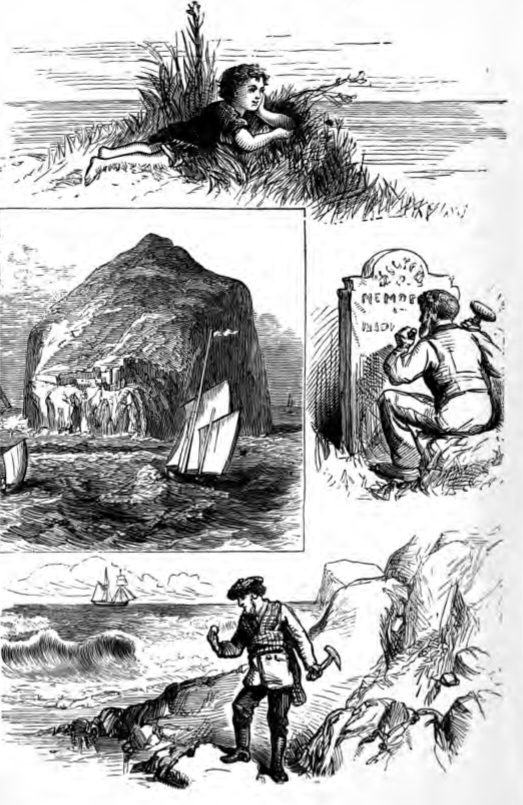

the world. “Viewed from the Moray Firth on a clear morning,” writes Hugh

Miller, “the entrance of the bay presents one of the most pleasing

scenes I have ever seen. The foreground is occupied by a gigantic wall

of brown precipices, beetling for many miles over the edge of the Firth,

and crested by dark thickets of furze and pine. A multitude of shapeless

crags are scattered along the base, and we hear the noise of the waves

breaking against them, and see the reflected gleam of the foam flashing

at intervals into the darker recesses of the rock. The waters of the bay

find entrance through a natural postern scooped out of the middle of

this immense wall. The huge projections of cliff on either hand, with

their alternate masses of light and shadow, remind us of the out-jets

and buttresses of an ancient fortress; and the two Sutors towering over

the opening, of turrets built to command a gateway. The scenery within

is of a softer and more gentle character. We see hanging woods, sloping

promontories, a little quiet town, and an undulating line of blue

mountains, swelling as they retire into a bolder outline and a loftier

altitude, until they terminate, some twenty miles away, in the

snow-streaked, cloud-capped Ben Nevis.” The “little quiet town,”

appearing in the distance like a few irregular lines on the margin of

the panorama, was the scene of Hugh Miller’s first joys and sorrows. He

was just waking to the pleasures of boyish life when his father, “a

patient, hardy man, of thoughtful brow,” having left his home with kind

farewells and hope of speedy return, steered the sloop of which he was

the owner along the channel between the Sutors and out into the Moray

Firth, but was never again seen in Cromarty. The vessel foundered in a

tremendous storm, but Hugh often gazed wistfully over the waters in the

hope of seeing it return.

“Alone he climbed the

grassy steep,

And waited for his father’s sail,

But vainly stayed till from the deep

The sun-set trail

Had faded, and the evening star

Gleamed like a silvern shield beheld afar.

“The seaman never would come back

For greeting in his own dear town,

The tempest shriek’d along his track,

And he went down

The depth which hath no upward stair,

And ocean-flowers were tangled in his hair.

“The boy was fatherless, and felt

His mother's tears fall on his face ;.

But grief smote faintlier, and he dwe'.t

Amid the grace .

Of fairy sisterhoods, who bore

The antique symbols of romantic lore.

“He dreamt of ancestors who smote

The haughty galleons of Spain,

And saw the lion-banner float

O’er that blue’ main

On which in pomp of starry lines,

The Southern Cross augustly, calmly shines.

“And Scotland with its haunted roods

Of vale, and crag, was all his own,

And in the unpathed birchen woods,

In sea-caves lone,

And where high snow-crowns glimmer cold,

For him were legends of old days unrolled.

“What wealth for him beneath the arch

With cloud-wrought imagery inlay’d,

What joyance in the year’s swift march,

Its light and shade,

Its silvern frost-work, and its flowers,

Impurpled hills, and sun-illumined showers!

“The school-house with its seaward door

And roof of thatch his haunt became;

But what to him the master’s lore,

Or scholar’s fame

Too careless of his tasks to reach

Beyond the glories of his native speech!

“With wild companions he would roam

From ledge to ledge through idle days,

Or light the wave-hewn cavern’s dome

With ruddy blaze

Of fires high-heap’d with broken spars

Wash’d from tofn keels on rocks and foamy bars.

“And thus he grew high-hearted, free,

The gleam of genius in his eyes,

Skill’d in the ancient poesy

Of changeful skies,

And his own Firth and Sutors, yet

Disdaining rule as untamed horse the bit.

“And who could see the boy’s heart swell

With scorn of bonds, and bard-like love

Of lovely things, and not foretell

That he would prove

To Cromarty a larger shame,

Or sphere it in the zodiac of fame?”

When Hugh’s school-days

were over it became necessary for him to learn a trade, and he decided

on being a mason. He was influenced in the choice of this trade by the

fact that masons had long winter holidays: not that he wished so much to

have time for amusement, but for improving his mind by careful

observation of nature, and by acquaintance with the best works in

English literature. He was apprenticed to the husband of one of his

maternal aunts, and getting a suit of mole-skin clothes and a pair of

heavy shoes, was ready for his first essay in real work. His master was

quarrier as well as builder, and he had to go with him into one of the

Cromarty quarries to help in hewing stone. Though his hands were soon

blistered and his limbs wearied, he enjoyed the out-door life; for birds

and bees gladdened him with their wild music, his curiosity was excited

by the strange marks on the riven rocks; and when he sat down to his

mid-day meal he could gratify his love of fine scenery by looking on the

Firth with the wooded promontories rising above it, and away to the

white peak of Ben Wyvis.

Our next glimpse of him is on the bank of the Conon, where with his

master he was employed in building a farm-steading. The latter was

unable to get work on his own account, and Hugh had to accompany him as

journeyman’s apprentice, and was lodged with about four-and-twenty men

in a large building open from end to end. Rough beds, consisting of

undressed planks, were on each side, and there was a row of fires for

cooking at one of the gables. Hugh had to cook for himself and his

uncle, and managed to serve up some extraordinary messes. By practice,

however, he became a tolerable baker, and made oat-cakes which pleased

his own taste very much. But to the dismay of his uncle, the meal in the

chest was rapidly diminishing, and he was limited to two cakes a week.

He consented to this arrangement, and one evening early in the week when

the old man was out, mixed about a peck of meal and rolled it out into

the circumference of a grindstone, and then put the pieces into which he

divided it before the fire. While he was busy with his baking, his uncle

came in, and glancing at the huge ring of meal on the lids of two boxes

which, placed side by side, had formed an extemporary table, and at the

twenty sections of the cake which were hardening at the fire, abruptly

asked, “What’s this, laddie? are ye baking for a wadding?” “Just baking

one of the two cakes, master,” he replied; “I don’t think we’ll need the

other one before Saturday night.” There was a roar of laughter through

the barrack, in which the old man had the good feeling to join, and

always after Hugh baked as much and as often as he liked.

He spent no more time than was necessary in the barrack, for the men

were coarse and dissolute; but there were delightful walks in the

neighbourhood of the Conon, and in “the red light of gorgeous sunsets”

he inspected the Druidic stones on Redcastle Moor, and the grim old keep

of Fairboum the freebooter, or mused in woods luminous] with the blue of

crowded hyacinths. Poetry attended him in those evening rambles, and

seeing in a solitary clmrcliyard a dial-stone encrusted with lichens, he

wrote the following with other verses :—

"Grey dial-stone, I fain

would know

What motive placed thee here,

Where sadness heaves the frequent sigh,

And drops the frequent tear.

Like thy carved plain, grey dial-stone,

Grief’s weary mourners be;

Dark sorrow metes out time to them—

Dark shade marks time on thee.”

When Hugh Miller had

completed his apprenticeship he worked for some time in the country as a

journeyman mason, and then went to Edinburgh, and was employed in the

erection of a manor-house near that city. He was joined in his lodgings

by a mason’s labourer, who, though not getting more than half the wages

of the skilled labourer, was in much better circumstances than the

greater number of them, being godly, and consequently sober and frugal.

In his constant cheerfulness the man presented a remarkable contrast to

another labourer, who, though aristocratic in the cast of his face, was

made miserable in appearance by the feeling that he was near to riches

and honours without being able to grasp them. Only a

marriage-certificate was needed to establish his claim to the earldom of

Crawford, and twenty times in a day his ears were saluted by the cry,

“John, Earl Crawford, bring us anither hod o’ lime.” Prom Edinburgh Hugh

Miller went back to Cromarty, and being in delicate health, had to rest

for some months. It was then that he gained a higher knowledge than had

been afforded by the sea-beach, and the old sea-levels, the woods and

the quarries—the knowledge of Christ by faith. From boyhood he had been

familiar with the doctrines of the Scotch Church, as taught in

catechetical exercises, but they had not quickened his soul to spiritual

life. They were in his mind, but they lay there dead and cold as the

ichthyolites which he struck out of the rocks. He knew the creed only as

an ancient petrification; and so slightly did it influence him that at

times he went to the verge of scepticism. He was never an infidel, yet

was not without intellectual tendencies to unbelief. Happily for himself

and the world he was at length drawn to the Saviour. His affliction gave

emphasis to the evangelical ministry under which he sat, and to the

faithful and tender expostulations of a converted friend; and he was

induced to feel his way to the living Person of the Redeemer. The

movement was slow and quiet, but it issued in abiding rest and peace for

his heart. Conversion in his case was not like a sudden storm hurling1

impetuous waves against the Sutors, but rather like a beautiful morning

widening in calm light over the waters of his native bay.

When sufficiently

improved in health, he began to hew tombstones; and while thus employed,

found a new interest in Cromarty in the friendship of the parish

minister, Alexander Stewart. While he was busy with epitaphs and

mortuary devices, the minister would stroll to him to find in congenial

talk a relief from the toils of the study. They also met frequently in

the evening, and while the setting sun burnished the cliffs and sent

shafts of golden light through the openings in the woods, walked

together on the beach or the hill-side: the one rolling out his

treasures of theological lore, the other welding the links in a chain of

geological argument, or expatiating on the significance of a newly-found

fossil. On the Sabbath Miller was in the church, with shaggy head bent

towards the floor, and face inexpressive as that of a Red Indian, yet

gathering all the sermon into his mind, and rejoicing in the original

thoughts and vivid illustrations which at the time of Mr. Stewart’s

ministry gave to the Cromarty pulpit the aspect of “a throne of light.*

Miller’s literary efforts and geological researches and discoveries

showed him to be worthy of a higher position than that of a hewer of

tomb-stones, and he was offered the accountantship of a branch bank. He

accepted the offer; and having an improved income and a higher social

status, was married to a young lady who was, like himself, an enthusiast

in literary and scientific pursuits.

But a greater scene than

that of a banking-house opened before him. Scotland was agitated by

ecclesiastical controversy, and his convictions and predilections were

with those who were determined at whatever cost to take Christ as the

only Head of the Church. He addressed to Lord Brougham a spirited and

eloquent letter on the questions in dispute. The manuscript, by a

seemingly accidental circumstance, fell into the hands of Dr. Candlish,

who at once concluded that the writer was the man needed as the editor

of the newspaper the Free Church party contemplated publishing.

.Application was made to him, and in a few months he was seated at the

editorial desk. “The Witness” came out twice a week, and was enriched by

him not only with leading articles on the usual topics, but also with

geological and other sketches, which were afterwards collected and

reprinted in goodly volumes. Considering his early disadvantages, his

mastery of the English language was wonderful; and whether describing

the caves above the Cromarty Firth, or the precipices of the Bass Rock;

whether narrating his adventures along the awful cliffs of ! the

Hebrides, or attempting an imaginary restoration of forests which are

now coal-beds, and seas which rolled their waves where now harvests

ripen and gardens glow with arabesque of flowers, he is always animated

and picturesque, and not seldom sublime.

In 1845 he spent his holiday in England; and an incident in connection

with his visit to York may be mentioned. He had to sleep in a

double-bedded room, and was in his own bed some time before his

fellow-lodger arrived. He noticed that the man prayed long and

earnestly, and afterwards ascertained that he was a Methodist. On the

following day he went to the minster, and looked with admiration on the

great pillars, with their capitals garlanded with stony foliage, the

rich decorations of the vaulted roof, the gorgeous windows reflecting

variegated splendours on the pavement; but it seemed to him that the

spirit of religion was wanting. The poetry rather than the sacredness of

the building impressed him, and without intending irreverence he walked

up the nave with his head covered. Two of the vergers espied him, and

one of them, with considerable gesticulation, cried out, “Off hat, Sir;

off hatand the other", in a commanding tone, exclaimed, “Take your hat

off, Sir.” The hat was removed, with an apology, and he heard one of the

officials say to the other, “Ah, a Scotchman; I thought as much.” The

service, notwithstanding the aid of the great organ and the surpliced

choir, struck him as being a tame mechanical affair, and he came to the

conclusion that the devotion of the Methodist of the previous evening

was more likely to move the world. Hugh Miller was a Christian man, and

though science was dear to him the Gospel was dearer, and one of the

great labours of his life was to show that there is a real harmony

between the facts of nature and the teachings of the Bible. But he

overworked his brain, and shot himself in a fit of madness. It is

lamentable to think of a man with such a genial heart and such a

magnificent intellect, coming to so sad an end; but as he was not

accountable for his last sad act, there is no reason for doubt as to his

final salvation.

His genius and virtues are honoured by a monument in his native town,

but his is more than a local reputation :

The fame which dawned in

Cromarty

Has widened over land and sea,

And Miller shines on high

Like great Orion when he stands

With mighty sword and glowing bands,

A splendour in the sky.

The sons of labour proudly claim

The light of his unsullied name,

And praise the toiling hand

Which, though with many a rough stone

Threw, fragrance as of costliest nard

Wide o’er his native land.

A group of muse-encrowned men,

Great masters of the golden pen,

His lofty powers discuss,

And own him of the brotherhood,

Of glorious front and fiery blood

Who make time luminous.

And Science bends her shining head

Above his deep, sepulchral bed,

And weeps innumerous tears

Still mourning that to raise her state,

He took so largely from the date

And triumph of his years.

Religion, with the upward look

And hand laid on the Holy Book,

Attests his godly worth,

And ranks him with the lofty ones,

Whose words and deeds are benisons,

To light the dim, sad earth.” |