DUNCAN MATHESON, an

evangelist who worked for Christ, with both hands earnestly was born at

Huntly in Aberdeenshire, on November 22nd, 1824. His parents were very

poor, and there was nothing of the golden romance in his boyhood which

is so fascinating in the narrative of Hugh Miller’s exploits on the

beach, and up the cliffs of Cromarty. When in bed he often wept as he

thonght of the labours and anxieties which paled his mother’s cheek, and

was eager for the time to come when he would be able to lighten her

burden. Though his heart was affectionate, he resented injustice, and

one day when the master of the school he attended began to beat him for

an act of boyish mischief with which he had been wrongfully charged, he

became so violent in his muscular demonstrations that the tawse had to

be laid aside. Most of the Established Churches in that northern

district were, as to religion, cold as the snow on Ben Nevis; but

Duncan’s grand-uncle, George Cowie, who was minister of an Independent

Church in Huntly, preached the Gospel with great power, not only in the

town, but also in the villages to which he had access, and encouraged

penitent sinners to trust in Christ, by his frequent and favourite

saying, “There is life for a look; there is life for a look!”

Many were converted and

established in grace by the Divine energy which accompanied his

ministrations. When he died, thousands of men and women to whom his

sermons had been reviving as the palms and cool wells to the fainting

pilgrims in the desert, followed him to the grave, and his tombstone was

appropriately inscribed with the words, “They that be wise shall shine

as the brightness of the firmament; and they that turn many to

righteousness, as the stars for ever and ever.” In after years Duncan

often knelt at that grave, and prayed that he might be endued with a

zeal for Christ impassioned as that of his sainted relative, and that he

might have a like success in winning souls for heaven. Religion, as it

was represented in his home, and in the character of godly friends of

the family, appeared to him in boyhood as a possession to be desired,

and his conscience was aroused by sickness, and by the death of a

beloved sister, but he did not apply himself with thorough earnestness

to the work of salvation. His heart, clinging to the world, urged delay;

yet he had a clear perception of the necessity of Divine grace,

especially in a minister of the Gospel. An offer was made to him of such

pecuniary help as would enable him to enter a University, on condition

that he should study for the ministry; but he would not intrude on an

office for which he had no spiritual qualification, and said, “A

minister ought to be a converted and a holy man. I am not that. I cannot

do it.”

Indulging in dreams of artistic renown, he determined to be a sculptor,

and made choice of the employment of stone-hewing, as a step towards the

majestic images he hoped one day to bring out of Italian marble. After

working about six months with mallet and chisel, his master sent him

into the quarry, where his visions of beautiful statuary were soon

dissipated. He became expert as a builder, and obtained work in

Edinburgh. There he attempted to get rid of the serious thoughts that

still haunted him, and instead of attending church, spent his Sabbaths

in novel-reading, or in rambles through the romantic scenes in the

neighbourhood of the city. In 1845, lie was called to his mother’s

death-bed, and was deeply affected as with tender pathos in her voice

she urged him to follow Christ and meet her in heaven. Returning to

Edinburgh he again endeavoured to close his heart to the work of

righteousness, but was aroused by a sermon preached by the Rev. A.

Bonar, and began to seek salvation. So intense was his desire for

acceptance in Christ, that he prayed all day, and again prayed on every

one of the seventy steps he had to climb to his lodgings. By the

ministrations of Mr. Bonar, and. the counsels of other good men, he was

encouraged to cast his soul on the atoning grace of the Lord Jesus, and

had a sense of ineffable peace while meditating on the words, “For God

so loved the world, that He gave His only begotten Son, that whosoever

believeth in Him should not perish, but have everlasting life.” His joy

in his new relation to God was at first unbounded, but clouds

intervened, and for some time he was in deep despondency, fearing that

he had been deceiving himself with unwarranted assurances of the Divine

favour. After a stem struggle with doubts and fears he obtained the

victory, and henceforth went on his way with gladness in his heart and

songs on his lips. Knowing the faith that unites the soul to Christ, he

wished to publish it, and began that course of evangelistic labour by

which he rendered far greater service to his fellow men than he could

have done if he had worked his dreams of the sculptor’s glory into

recognised facts, and had even excelled the grace and symmetry of the

Elgin marbles. The Duchess of Gordon having heard of his successful

aggressions on the kingdom of Satan, engaged him as a Missionary at a

salary of £40 a year. Huntly, and the adjacent country, were the scenes

of his efforts, and he was encouraged to diligence by the aged saints

who had been the friends or converts of Mr. Cowie. Visiting Isobel

Chrystie who was ninety years old he was delighted to hear her thus

break out about the dying thief: “That was a gey trophie to gang throw

the gowden gates o’ heaven. I’m thinkin’ there was a gey steer amo’ the

angels; but nane o’ them would try to pit him oot. Na, na; Christ brocht

him ben!” Another venerable servant of God said to him, “Haud in wi’

Christ; whatever happens, aye think weel o’ God; and tak care o’ yoursel’;

for, ye ken, a breath dims a polished shaft.”

Mr. Matheson wished to serve his generation not only by his voice, but

also by the extensive circulation of religious tracts. Having spent his

last penny in this work, he was lifting up his heart to God for help,

when the thought came into his mind, “If I could get a printing press I

could make as many tracts as I could use.” He went on praying for a

press for several months, and then discovered that an old one, with a

set of worn types, was for sale. He quickly made the purchase, set up

the press in his room, and wrote on it “For God and for eternity.” His

first attempts at printing ended in failure, and once when he had got a

page composed, and flattered himself that he was at last successful, had

the mortification of seeing the whole suddenly fall into confusion. But

he persevered, and was at length able to print two thousand four-page

tracts in a day. “How,” he remarked, “I did toil, and sweat, and pray at

it! Some nights I never slept at all, but went on composing. My

constitution was strong, and night after night was spent at the work.”

In 1854, he witnessed the departure of British troops for the Crimea. As

he looked on the brave men on their way to deadly conflict with the

gigantic power of Russia, his sympathies were excited, and he began to

pray that God would open a way for him to follow them, that he might

direct them to the Captain of their salvation, and cheer them in their

hardships by rehearsing in their ears the melodies of eternal love.

Through what appeared to be a remarkable interposition of Divine

Providence, lie was soon engaged in those labours of love. The Countess

of Effingham wished to send a Missionary to the Highland Brigade, and

Mr. Matheson received a letter, the substance of which was, “If you are

still in the mind to go to the East, reply by return of post, and please

say when you could start.” He felt sure there was a mistake, but took

the letter to the Duchess of Gordon, who on reading it, exclaimed, “How

strange, I have been praying that God would incline you to go, and

others have been praying also. If there is a mistake, I will send you

myself.” The letter was intended for a licentiate of the Free Church

bearing the same name, but it fell into the right hands. The evangelist

was soon in readiness for his mission to the Crimean encampment. Before

leaving England he stayed a short time in that house Beautiful, the

rectory at Beckenham, and received a parting blessing from the saintly

and apostolic Dr. Marsh. Arriving at Constantinople, he embarked as

speedily as possible for the Crimea, and though landing at Balaklava

with the report of cannon in his ears, was cheered on finding that his

text for the day was, “The Lord preserveth those that love Him.” The

proud names of Alma and Inkermann had been added to the long roll of

British victories, and the “Six Hundred” had ridden into the valley of

death, “Charging an army, while all the world wondered!” but the camp

had become an almost indescribable scene of destitution and

wretchedness. The hospitals were crowded, and ships were constantly

bearing away the sick and wounded to Scutari. Many of the soldiers on

duty were in rags, and haggard with toil and hunger. Even officers, no

longer glittering with martial insignia, were so bespattered with mud as

scarcely to be distinguished from the privates. Mr. Matheson, with

characteristic ardour, began to administer to the bodily and spiritual

wants of his countrymen. He was cheered in his work by the Christian

sympathy of Hector Mac-pherson, drum-major in a Highland regiment. The

first Sabbath after his arrival, he and Hector retired to a quiet

ravine, where they read and prayed together, and united in singing the

psalm to which they had resorted when in trouble at home:

“God is our refuge and our

strength,

Id straits a present aid ;

Therefore, although the earth remove,

We will not be afraid,”

In order to be near the

army he lodged in an old stable infested with rats, and admitting the

bleak winds through many crevices in the walls and roof. Yet he was so

happy in the consecration of his life to the Saviour, that even of that

miserable hovel he could write, “I have a perfect palace, and I have

decorated the walls with copies of the 'Illustrated London Hews.' I fear

it is too good to last, but it is in the Lord’s hands. How contented I

feel with all, and how well it is, that when young I learned to help

myself. I am as happy as a king, yea, ten thousandfold more so than one

without grace.” He was out all the day, gladdening the hearts of

destitute soldiers with gifts of food and clothing, distributing Hew

Testaments, attending to the sick and wounded with a hand gentle as that

of a woman, and speaking now in his native Doric, and now in broken

French and Italian, words of wisdom and good cheer in the name of

Christ. One evening he was returning weary and sad from Sebastopol to

his rude lodging in Balaklava. At almost every step he sunk to the knees

in mud; but the stars were shining serenely in the heavens, and as he

lifted his eyes to their quiet beauty he was reminded of the beatified

spirits before the throne of God, and began to sing the Scottish

paraphrase:

"How bright these glorious

spirits shine

Whence all their bright array;

Now came they to the blissful seats

Of everlasting day?

“Lo! these are they from sufferings great,

Who came to realms of light,

And in the blood of Christ have washed

Those robes which shine so bright."

The following day was

stormy, and Mr. Matheson saw a soldier in rags, and almost shoeless,

standing for shelter under a verandah. He spoke kindly to him, and gave

him half a sovereign to get shoes. His kindness opened the heart of the

soldier, who said, “I am not what I was yesterday. Last night, as I was

thinking of our miserable condition, I grew tired of life, and said to

myself, "Here we are not a bit nearer taking that place than when we sat

down before it. I can bear this no longer, and may as well try and put

an end to it.’ So I took my musket and went down yonder in a desperate

state about eleven o’clock; but as I got round the point, I heard some

person singing, "How bright these glorious spirits shine" and I

remembered the old tune and the Sabbath-school where we used to sing it.

I felt ashamed of being so cowardly, and said, "Here is some one as

badly off as myself, and yet is not giving in." I felt he had something

to make him happy, of which I was ignorant, and I began to hope I too

might get the same happiness. I returned to my tent, and to day I am

resolved to seek the one thing.” "Do you know who the singer was?” asked

Mr. Matheson. "No,” was the reply. "Well,” said the Missionary, "it

wasI.” Tears filled the soldier’s eyes, as he held out the half

sovereign to be taken back, saying, "Never, Sir, can I take it from you,

after what you have been the means of doing for me.”

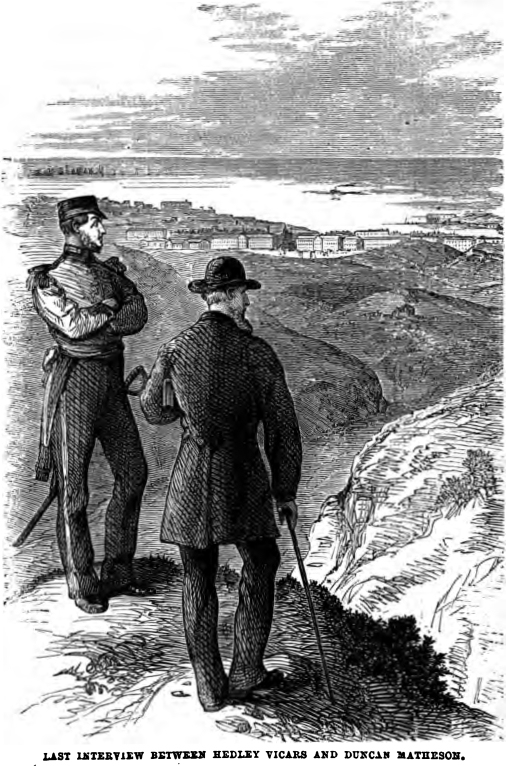

When Mr. Matheson first met Hedley Vicars he felt his heart at once

drawn to him, and rejoiced greatly in religions conference with that

brave soldier of Jesus Christ. One entry in his journal has a deep and

tender interest: “At Sebastopol. Met with Dr. Cay and Major Ingram in

Vicars* tent. We had prayer and reading the Word together. It was to us

all a well in the desert, a bright spot amidst surrounding gloom. We

blessed God on hearing that a day of national humiliation and prayer was

appointed. Cay and Vicars accompanied me on my way. After Cay left us,

Vicars and I stood on the plateau above Sebastopol—the doomed city, as

it was often called—lying in its beauty before us. The sky was without a

cloud: the sea was as calm as a pond. It was on one of those sweet

evenings you never can forget. Our conversation was on the purity,

blessedness, and endless peace of heaven, where the din of battle shall

never be heard, nor the strifes of earth be known. We expressed to one

another much longing to reach it. Speaking of some who had gone, we

remembered Peden at the grave of Cameron, exclaiming, *O, to be wi'

Ritchie!" and our feeling was the same ; we could hardly part. He agreed

to meet and spend a day with me at Balaklava.** But they never met again

on earth. The day oh which Vicars intended renewing his fellowship with

the Missionary, he experienced a sudden transition from the Crimean

camp, to the steps of the everlasting throne; and from the tumult of the

cannon’s “adamantine lips,” to “a sevenfold chorus of hallelujahs, and

harping symphonies.”

After the fall of Sebastopol, Mr. Matheson spent six weeks in Scotland

for the purpose of recruiting his health which had been broken by his

excessive labours, and then went back to the Crimea, taking with him a

large stock of Bibles and Christian books. He had shown such kindnesses

to the men of the Sardinian army, that he was known as “the Sardinian’s

friend,” and was gladdened by their eagerness to obtain the Holy

Scriptures. Eighteen thousand copies of the Word of God which had passed

through his hands, were carried by them into Italy. When peace was

proclaimed, he had access to the Russians, and gave them the Hew

Testament in their own language. The Cossacks especially appreciated his

acts of Christian love, and some of them in the exuberance of their

gratitude embraced him, a proceeding more gratifying to his heart than

agreeable to his nostrils. Leaving the Crimea he went to Constantinople,

and thence to Egypt. He also visited Italy, and while appalled by the

immoral tendencies of papal superstition, was cheered by seeing numerous

indications of a desire for a nobler life than was possible under the

malign influences of the Vatican.

In 1857, Mr. Matheson was engaged in evangelistic labour in Cumberland,

and also originated a periodical called, “The Herald of Mercy,” which

reached a circulation of over thirty thousand a month. He married a

Christian lady, and went to reside in Aberdeen, extending his Missionary

operations from that city to almost every part of Scotland. His success

in Dundee was extraordinary, and his memory is fragrant as the cinnamon

and spikenard of a Syrian garden to many of the townspeople. One Sabbath

evening, he addressed a crowded congregation in the Hilltown Free

Church. His text was, “And these shall go away into everlasting

punishment; but the righteous into life eternal.” With graphic power and

deep pathos he pictured the sinner’s eternal banishment from God, and

effectually illustrated his subject by referring to the loud wail of

agony, he had heard when in the East, from a crowd of Circassians who

were being driven from the mountains, to whose crags they had so fondly

clung, to exile in strange lands. Solemn awe rested on the congregation,

and sobs and tears and pallid faces, told of the feeling that was

stirring in many hearts. After the service, the vestries were thronged

by seekers of salvation; and numbers that night were enabled to say, “I

have found Him! I have found Him! ” In the autumn following that

service, open-air meetings were held in the Barrack Park, near Dudhope

Castle the ancient home of the Scrymgeours. Where the pomp and chivalry

of the royal standard-bearers once blazed, Mr. Matheson and a number of

ministers and laymen knelt for special prayer, and continued kneeling on

the grass for two hours, pleading for the baptism of the Holy Ghost.

When the prayer was ended, a heavy rain came down, and the people began

to leave, but the voice of Duncan Matheson was heard crying, “Perhaps

God is trying us by the rain; let us wait a little.” About three hundred

remained, and soon the rain ceased, the sun shone between the parting

clouds, and a wonderful power rested on the whole company. One who was

present, wrote, “Till memory fails, or the more excellent glory of the

unveiled face of Immanuel, obliterates the remembrance of faith’s

brightest visions on earth, it is impossible for us to forget the awful

nearness of God at the time, the overpowering sense of blended majesty,

love, and holiness, and the soft, pure radiance of the Redeemer’s face

that chased the dark shadows of doubt and sin away from many a soul.

After this visitation many were saved. Some of the incidents connected

with Mr. Matheson’s work in Dundee are very beautiful and touching.

A girl who had wandered

into sin, returned to her home, and was thus greeted by the grey-haired

mother: “O, my Annie! my Annie! my ain lost Annie! I never thocht I wad

hae seen ye mair. But the gude God has been better to me than a* my

fears. Are we ever gaun to pairt again, Annie?” “Never, mither, never,”

was the reply; “Jesus has saved me Him-sel’, an’ He has promised to keep

me, an’ He will never brack His word. We'll never pairt, mither; na, by

His grace, never, never.” And they did not part until Jesus came, and

took Annie to Himself. A godly woman whose ' husband had been a

drunkard, and who had been beaten by him on account of her godly ways,

went to her minister, saying, “ I am happier than I was on my marriage

day. God has heard my prayer; my poor husband is converted; he is like a

lamb now, and thinks he cannot do enough to please me. O, Sir, if you

had but seen him the other night holding family worship for the first

time! It was like heaven upon earth! There wasn’t a dry eye in the

house, and our little lassie looked up in his face and said, ‘Father,

ye’ll win to heaven noo, an’ I’ll gang wi* you, an’ we’ll a* be there. I

never thocht I would like to gang to heaven afore.’ ”

Mr. Matheson had a remarkable aptitude in preaching at feeing-markets

and village fairs. When other means failed he often got the attention of

the, shouting, laughing, crowd, by saying in a familiar manner, “I will

tell you a thing that happened while I was in the Crimea.” There would

be an almost instant hush, and after giving a stirring narrative of

British heroism, or picturing some feature in the scene of flame and

blood before Sebastopol, he preached Christ and eternity until

thoughtless hearts were troubled, and lips which to that hour were

profane and blasphemous, began to quiver with emotion. In one place the

manager of a penny theatre challenged Mr. Matheson and his companion to

go on his platform and try if they Could speak there. To his

astonishment the challenge was accepted, and Mr. Matheson, standing on

the boards which had been intended only for histrionic vanities,

addressed the multitude before him in wdrds of solemn warning and

affectionate entreaty. On another occasion, when Mr. Matheson and his

friends were preaching near a showman’s van, the magic bottle was

brought out, and the mountebank glancing towards the preachers said,

“Talk of revivals! Here is something that will revive yon.” The people

thought this very witty, and responded in peals of laughter, which for a

moment seemed to disconcert the evangelists. But they soon recovered

their courage, and throwing their hearts and voices into the melody of

the twenty-third psalm, drew the greater part of the crowd from the

showman. The green pastures and the still waters, proved a stronger

attraction than the conjuring tricks on the stage, and tears streaming

down numbers of cheeks, attested the pathos of the story of the Good

Shepherd seeking the lost sheep, as it was told by those devoted

servants of Christ. Mr. Matheson was preaching at a market in the north

of Scotland, from the words, Behold, He cometh with clouds; and every

eye shall see Him.” A scoffer came up, and with a sneer cried out, “Ay,

but when is He coming?” The preacher held up the Bible in his hand, and

looking round on his audience, said, “Ah, friends, you see this is a

wonderful book. Eighteen hundred years ago it predicted that there shall

come in the last days scoffers, walking after their own lusts, and

saying, ‘Where is the promise of His coming?’ I call you to witness that

the prediction is just now fulfilled. What do you think, Sirs. Is not

the Bible true? ‘He that shall come, will come, and will not tarry.’

”The reply silenced the objector, and the sermon was continued without

further interruption. Those open-air services were effectual in the

conversion of many souls, and entitled Mr. Matheson to be regarded as

“an unmitred Archbishop of Open-air.”

Being at the close of 1861 depressed in mind and body, he said to a

friend, “ Come, and let us visit St. Andrew’s and see the place where

the old Scottish heroes fought their good fight; it will stir and cheer

us, and perhaps God will give us of their martyr spirit.” They visited

the spot where George Wishart was burned for the truth, and where

Rutherford breathed out his soul in the triumphant exclamation, “Glory,

glory dwelleth, in Immanuel’s land.” Then going into the cathedral yard,

they wept and prayed on Rutherford’s grave, and having consecrated

themselves more fully to the service of Christ, sang “Rock of Ages” and

44 There is rest for the weary.” That solemn hour was frequently

reverted to by Mr. Matheson as a cheering memory for his darker hours,

and as an incentive to diligence in his work, and his preparation for

eternity. His excessive exertions induced disease, and after vainly

seeking health on the Continent, and in different parts of Scotland, he

went to Perth, where he ended his useful career in peace and hope. In

his last days he told his children that the chariot was coming to carry

him to glory, and bade them trust in and love Jesus, so that they might

meet him in heaven. He had many cheering words for his wife, and assured

her that the Lord would take charge of her and their little ones.

“Mary,” he said, "I have another text to give you to-day. It is this: 'A

Father of the fatherless, and a Judge of the widows, is God in his holy

habitation.’” Another time he said, 44 Mary this room is filled with the

heavenly host. Had I strength how we would sing!” The lines, in which

Dr. Yalpy at the close of life expressed his desire and his belief, were

frequently repeated by him:

"In peace let me resign my

breath,

And Thy salvation see;

My sins deserve eternal death,

But Jesus died for me.”

When his friend, the Rev.

John Macpherson, went to see him, he said, after talking of Christ and

glory, "I have cast my five fatherless children upon the Lord, and all

shall be well.” Prayer having been offered, he wished to have singing.

"Man,” he said, " don’t get singing enough; I want to sing; will you

help me?” They were about to unite in “Shall we gather at the river,”

when cramp came on, and with the cry on his lips, “Lord Jesus, come

quickly! O, come quickly!” he passed through death to eternal glory.

“Thus, writes Mr. Macpherson, “departed a right brave and great-hearted

man,—the man, who above millions had lived for God; the man who, above

most men, had laboured for souls and for eternity.” He died on September

16th, 1869, and his friends, mingling praises to God with their tears

and lamentations, buried him according to his own request in the new

burial-ground at Scone.

Life and

Labours of Duncan Matheson

By the Rev. John MacPherson (1876) (pdf) |