NORMAN MACLEOD was of

Highland descent, and was not without genealogical glories, but rejoiced

more in a father and grandfather who were worthy ministers of the Scotch

Church, than in being able to trace connection with the ancient lords of

the tartan and the claymore.

There is in Argyleshire a wide romantic parish, named Morven, which has

a loch on each side, and the Sound of Mull in front. The general outline

of the parish is bold and rugged, but it is not without features of

beauty. With dark precipices and sombre moorlands, there are bright

melodious bums, lovely glens and rounded hills to which the oak, the ash

and the birch, lend the grace of their foliage. On one of the hills,

there was a number of years since an unpretending building known as the

Manse, or the House of Finuary. The glebe on which it stood, consisting

of about sixty acres, was broken into green terraces, and terminated in

a grassy flat in a line with the beach, distinguished as “the Duke of

Argyle’s Walk.** The House of Finuary was occupied by Norman Macleod’s

grandfather, who was minister of the parish. A family of sixteen sons

and daughters enlivened the manse, and sported about the glebe. The sons

were taught by a tutor, who had gained honours in one of the

Universities, and the daughters by a kind-hearted governess, who stumped

from room to room on a wooden leg. But the minister and his wife

attended to the religious education of their children, and in a loving

manner strove to imbue their minds with thoughts of Christ the Mediator,

in Whose name they were to seek the pardon of their sins, and as the

King to whom they were always to hold themselves in submission.

Truthfulness, integrity, generosity, sympathy with the suffering were

affectionately urged upon and exemplified before them, in character and

action.

About two thousand souls, spread over an area of one hundred and thirty

square miles, constituted the pastor’s flock. For their accommodation

there were two churches, but with the exception of one or two pews

intended for the principal people of the parish, there was not a seat in

them. So primitive was the diet of the parishioners that a man had to be

sent over moors and stormy lochs, for a distance of sixty miles, to

obtain wheaten bread for the Sacrament. When the minister had nearly

attained his fourscore years he became blind. His youngest son had been

appointed his assistant and successor, but to the last his heart was in

the work in which he had been so long employed. The closing scene of his

ministry was very affecting. The Lord’s Supper was about to be

dispensed, and he went to the church to give his people a farewell

address. He was guided to the pulpit by his old servant Rory, but

mistook the side for the front. Seeing this, Rory stepped back and

taking his trembling hand, placed it on the book-board, so as to put him

in the right position for speaking to the people. He stood before them

majestic even in decay, high in stature, with face beautiful in its

saintly venerableness, and with long white locks which streamed down to

his shoulders. His words were few but pathetic, and the stout hearts of

the Highlanders were melted, and low sobs broke from them, when he told

them that they would “see his face no more.”

His death, which took place a little while after, was calm as Loch

Sunart when reflecting the lovely hues of a sunset in July. His wife,

and sons, and daughters, and the faithful old Rory, were grouped about

his bed. Rory, who had legs of unequal length and only one eye, but was

a skilful boatman, and useful in many ways on the land, and who had been

“minister’s man” for fifty years, did not long survive his master. He

had been laid aside for some weeks, when one evening he said to his

wife, “Dress me in my best; get a cart ready; I must go to the manse and

bless them all, and then die.” His wife thought he was delirious, and

hesitated, but he insisted on being obeyed. He was taken to the manse,

and with his Sabbath tartan wrapped about him, tottered into the parlour,

and as the family gathered round him, announced his errand: “I bless you

all, my dear ones, before I die.” Raising his withered hands, he offered

a short prayer for their welfare, then shaking hands with each of them,

and kissing the hand of his beloved mistress, he bade them farewell. He

died the following day.

The holy influences of the old manse life were felt in succeeding

generations. One of the sons born on the glebe was settled as minister

of Campbeltown in Argyleshire. He was the father of Norman Macleod, who

was born June 3rd, 1812. As a child he was bright and vivacious, and the

great talker of the nursery. His education was commenced in the Burgh

School, but he was quite as fond of play as of books. The town stands at

the head of a loch, which, forming a convenient harbour, was usually

lively with the sails and pennants of merchant-ships, yachts, and

Revenue-cruisers. Norman frequently visited the vessels that were moored

to the pier, and became expert in climbing shrouds, and familiar with

nautical phraseology. The stories of the sailors opened to him a world

of romance, and voyages to Archipelagoes set in golden seas, or to the

clime of the walrus and the white bear, frequently filled his

imagination. Much of the knowledge of maritime life he obtained while

sporting about the harbour was afterwards utilised by him in that

pleasant book, “The Old Lieutenant and his Son.” When he was twelve

years old his father sent him to Morven to learn the Gaelic language. He

boarded during the week at the house of the schoolmaster, but was always

at the manse on the Sabbath. Living at Morven was a great advantage to

him, not so much on account of the Gaelic, as of the educational

influences of his out-door life. His mind was impressed by a sense of

the grand and beautiful in the works of God as he saw peak rising beyond

peak in silent majesty, torrents leaping down the precipices, streams

rippling over polished pebbles, and woodlands glimmering with the light

of primroses and hyacinths. Emotions he could not then define kindled in

his heart, when, from the top of a favourite hill, he looked on lakes

and leafy slopes, and away over the shining sea to the blue cliffs of

the Hebrides.

In 1825, Mr. Macleod removed to Campsie; and Norman having completed his

Highland training, went for a year to the parish school. At the end of

the year he became a student in the University of Glasgow. His mind was

too discursive to attempt accurate scholarship; and English literature

and natural science had greater charms for him than the Greek of

Euripides, or the Latin of Cicero. In after years he reproached himself

with not having been more diligent in the classes, and lamented his lack

of skill in the ancient tongues. He was frequently at Campsie on the

Sabbath; and though always affectionate and deferential to his parents,

displeased them by the boisterousness of his humour and mimicry. His

vacations were spent either at Campsie or in the Highlands. Wordsworth’s

poems took up many of his leisure hours, and he delighted in reading

them in the sunshine that flickered through the foliage in Campsie Glen,

or where the leaves were ruffled by the breeze from northern lochs.

In 1831 lie began to study theology under Dr. Chalmers in Edinburgh. The

eloquent prelections of the great evangelical rabbi were to him awful in

their impassioned earnestness. He venerated his teacher as rising above

other men like Ben Lomond above its neighbouring peaks, and opened his

heart to the force of the immense yet benignant individuality by which

Chalmers was distinguished. Chalmers also was favourably impressed by

the open countenance, generous spirit and bright intelligence of the

student, and recommended him as being qualified to act as tutor to the

son of a gentleman, then High Sheriff of Yorkshire.

Though intended for the ministry, he had not given much attention to

personal religion, but the sickness and death of his brother James

softened his heart, and induced in him a conviction of the necessity of

living union with Christ. One night after he and his sick brother had

opened their hearts to each other, he prayed aloud; it was the first

time he had done so, and with great earnestness he asked for blessing on

himself and his dying brother. When he had risen and gone away, James

called his mother to his bedside, put his arms round her, and said, “I

am so thankful, mother: Norman will be a good man." This was the

beginning of a good work in his heart. After his brother’s death he

wrote:—

“It is all past. My dear brother is now with his own Saviour. I do

heartily thank God for His kindness to him; for his patience, his

manliness, his love to his Redeemer. May I follow his footsteps! May I

join with James in the universal song! I know not, my own brother,

whether you now see me or not. If you know my heart, you will know my

love for you; and that in passing through this pilgrimage I shall never

forget you who accompanied me so far.”

There is not any one point in his history to which the fact of

conversion can be definitely attached; for, in his case, there was

rather a succession of advances than a sudden spring from darkness to

light. But there was a change: he did seek the righteousness which is by

faith; and no experience in a Methodist Love-feast could be more

decisive as to simple trust in Christ for salvation, or as to the joy in

God which accompanies spiritual life than a number of entries in his

journal. When he left Edinburgh he went to Moreby Hall, the residence of

his pupil’s father, and thence to Weimar. The little capital had been

renowned as the abode of the great German writers—Goethe, Schiller,

Herder, and Wieland; and though they had passed away, the splendour of

their genius still lingered about the city. But whatever intellectual

advantages Norman gained while there, his religious sensibilities were

deadened by intercourse with the citizens, whose mental activities took

the form of Rationalistic attacks on God’s Word, and to whom the Sabbath

was but a secular festival. Though he kept aloof from vice and

scepticism, he indulged too freely in the abounding gaieties, but learnt

for life the lesson of the utter vanity and hollowness of worldly

society.

In October, 1835, he began attendance on a course of Divinity lectures

in Glasgow. His father having accepted the charge of St. Columba in

Glasgow, he lived with him. Other students, also, were boarders in the

house, among whom were John Mackintosh, of Geddes, who became Norman’s

dearest friend, and John C. Shairp, now the accomplished Principal of

the United College in St. Andrews.

In recording his reminiscences of those joyful days, the latter gives

the following portraiture of Norman:

“His appearance as he then was is somewhat difficult to recall, as the

image of it mingles with what he was when we last saw his face, worn and

lined with care, labour and sickness. He was stout for a man so young,

or rather I should say only robust, yet vigorous and active in figure.

His face as full of meaning as any face I ever looked on, with a fine

health in his cheeks, as of the heather bloom; his broad, not high,

brow, smooth without a wrinkle; and his mouth firm and expressive,

without those lines and wreaths it afterwards had; his dark brown glossy

hair in masses over his brow. Altogether he was, though not so handsome

a man as his father at his age must have been, yet a face and figure as

expressive of genius, strength and buoyancy as I ever looked upon.

Boundless healthfulness and hopefulness looked out from every feature.”

The boarders were under Norman’s care, and he was in a better sense than

Bolingbroke was to Pope their “guide, philosopher and friend.” Each had

a separate bed-room, but all met in a common sitting-room, and formed a

bright little group, of which Norman was the centre. When the work in

preparation for college-classes was done, and sometimes before, he used

to come from his own study in his grey-blue dressing-gown and broidered

cap, and entertain them with a swift succession of sunny thoughts,

romantic stories and recitations from the poets; or he would sing a wild

lay he, had heard on the hills of Morven; or he would bring a book with

him and give a reading from Sir Thomas Brown’s “Religio Medici,” or from

a discourse in which Jeremy Taylor had woven his golden fancies and

lavished his varied lore.

It was in Glasgow that he won his first honours as a public speaker. A

banquet was given to Sir Robert Peel in celebration of his election to

the Rectorship of the University. There was a large and brilliant

assembly, and Norman had to speak on behalf of the students. Though

inwardly trembling, he betrayed no sign of nervousness, and so manly

were his sentiments, and so distinct was the enunciation of his choice,

yet simple words, that every one present felt the power of a true

orator; and Sir Robert Peel was reported to have expressed admiration of

the speech to his father. It has been said that he was never on any

public occasion more thoroughly successful than in that appearance at

the Peel banquet.

In due time he was licensed as a preacher, and in 1838 was ordained to

the parish of Loudoun.

Some months after his settlement there, J. C. Shairp and a few other

college friends spent three days with him. They were the greater part of

the time in the open air, wandering by Irvine water and through the

woods, or reclining on a grassy bank with the shadow of spring leaves on

their faces, intermingled the melodies of Wordsworth and Coleridge with

arguments on high and sacred themes. When the time drew near for them to

part, they were saddened by the thought that they might never all meet

again, and the young minister got each of them to take a root of

primroses from the woods to plant in the manse garden, in memory of

their visit. This they did; the roots were planted side by side, and

were so cherished by Mr. Macleod that when he left for Dalkeith he had

some of them removed to his new abode.

That he entered on his duties in a becoming spirit is evident from the

following extract:

“I have got the parish of Loudoun. Eternal God, I thank Thee through

Jesus Christ; and under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, I devote myself

to Thy service for the advancement of Thy glory and kingdom. These words

I write this day the moment I hear of my appointment. I again solemnly

say, Amen. I have got a parish!—the guidance of souls to heaven ! I

shall at the last day have to tell how I performed my duties. Part of my

flock will go to the left; part, I trust, to the right. I, their pastor,

shall see this ! I am set to gather lambs to Christ. What a

responsibility! I do not feel it half enough; but I pray with all my

soul, heart, and strength that the great Shepherd may never forsake me.

Without Him I can do nothing; with Him I can do all things.”

He found the widest extremes of character and opinion in his parish. His

people were for the greater part farmers or weavers. Several of the

former were descendants of the covenanters, and retained not a little of

the stern Presbyterianism of their ancestors. The weavers were most of

them chartists, and some of them infidels of the Thomas Paine type. Mr.

Macleod at once set himself to grapple with the difficulties of his

position, and his energy was soon felt as a beneficial power in the

parish. He visited from house to house, organised a Sabbath-school, and

held special services on the Sabbath evening for those who had not

suitable clothes in which to appear at the ordinary place of worship.

When on his round of visitation in Darvel, a part of his parish, he

called on a poor and aged woman, who held strictly to covenanting

principles. She was in the midst of a group of neighbours and friends

who had been invited to meet him. Not being disposed to receive him as a

minister of Christ until he had given satisfaction as to his theology,

she put her tin trumpet to her ear, for she was very deaf, and with a

tone of authority that a moderator of a General Assembly could not have

exceeded, said, “Gang ower the fundamentals.” Sitting by her side, and

putting his mouth to her trumpet, he went through the leading doctrines

of the Confession of Faith, and as there was no heresy she accepted him

as a true servant of Christ. But a rehearsal of his creed was not

sufficient for chartists and sceptics. For a time they resisted him, but

he succeeded in his endeavours to disarm them of their prejudices, and

having won their confidence, was able to press the truths of the Gospel

upon them with good effect.

His heart was pained not only by what he witnessed of the demoralising

effects of infidelity, but also by the apathy of those who made a show

of religious belief and profession, yet were as to religious sensibility

inanimate as the imagery on the tombstones in the churchyard. There were

times when he was depressed by the fear that, notwithstanding the crowd

that filled the pews, aisles and stairs of his church, he was

accomplishing little in the way of moral and spiritual reformation; but

when he knew of any one receiving benefit from his ministry his heart

was full of thankfulness to God. He writes:

“I have had to-day much joy and much humility. A woman told me that I

had been blessed for the good of her soul, and given her joy and peace;

and I think she gave evidence from what I saw of her that she is a true

believer. She gave me likewise five shillings for any religious purpose.

She will and does pray for me. I wept much at this proof of God’s

love!—that I should be made such an instrument! But, blessed be God, He

can make a fly do His errands. He is good and gracious—and O! I hope I

may save some; I pray I may bring some to Christ, for His sake. May I be

humble for all God is doing for me! His blessings crush me! May they not

destroy me! May Christ be magnified in me!”

While Mr. Macleod was at Loudoun his mind was agitated by the great

conflict which led to the Disruption, but his sympathies were not

altogether with either party. In religious sentiment and ministerial

activities he coincided with the Evangelicals, and had an almost

unbounded reverence for some of their leaders, but could not act with

them in what seemed to him extreme and revolutionary measures. His

glowing nature, with its intense desire for the salvation of souls, had

no affinity with the iciness and the subdued Christianity of the

Moderates, but he was with them in upholding what he considered the

constitutional principles of the Church. He did his utmost to avert

secession by uniting with Dr. Leishman and the “Forty” in advocating a

policy of conciliation and compromise, but the Evangelicals had gone too

far to recede, the Moderates acted as if they did not care how soon they

were rid of men who practically asserted their conviction that a parish

minister had something more to do than to draw the stipend and make

himself agreeable to the heritors; and the fatal moment came when one

part of the Assembly and the Church was severed from the other. Had Mr.

Macleod thought only of his own ease and popularity, he would have gone

out with the seceding ministers, but he felt himself bound to remain in,

and help to rebuild the shattered Church. As a Free Church minister he

would have found an ample sphere for his energies and gifts, and a

position of high honour and large influence would have been assigned

him. But it was well for the Establishment that he and others

like-minded with himself adhered to it, and instead of allowing it to

become the sepulchral monument of a vanished life, strove to keep it up

as a temple, which, with the light of holy memories on its walls, and

the glow of a Divine flame on its altars, should still be venerable in

the eyes, and dear to the hearts of the Scottish people.

The Disruption occasioned many vacancies in parishes, and seven

applications were made to Mr. Macleod. He had no wish to leave Loudoun,

but felt it his duty to accept Dalkeith. He settled there in December,

1843, and began his ministry in that town, in a quaint old church, in

which gallery rose above gallery, each bearing an emblazoned device

showing the guild to which it belonged. Preaching evangelical truth in

simple and beautiful words, and in a manner that betokened earnest

desire for the salvation of souls, he could not fail to be popular; but

he was far from contenting himself with a large and appreciative

congregation. Dalkeith, though a small town, was not without its lapsed

classes, to whom ho extended his cares and labours. In order to interest

his own people in evangelical work, he instituted weekly meetings, at

which he gave reports of Missionary enterprise at home and abroad;

members of the Church who had the necessary qualifications were employed

in visiting the poor and neglected, and three mission stations were

opened amidst haunts of vice and squalor. So beneficial were these

operations that street brawls became far less common and the police had

to report a remarkable decrease in the number of arrests for

drunkenness.

In 1845, Mr. Macleod was sent by the General Assembly as one of a

deputation to the congregations connected with the Church of Scotland in

British North America. The old romance of Morven life came back to him

when shooting rapids, gliding over silvery lakes, or passing through

seemingly interminable forests with the majestic boughs of great trees

bending in wide arches over his head. But much as he enjoyed the scenery

and the adventurous travelling, he had still more pleasure in meeting

with Highlanders who remembered his grandfather, and were eagerly

affectionate in their inquiries about his father and his uncles and

aunts. A communion service at Pictou, in which the members of the

deputation officiated, powerfully affected him. Four thousand people

were assembled on a grassy hill near the town, and he thought he had

never looked on a sight so touching and so grand. As he watched the

expression of solemn joy on the long rows of Highland faces bending

towards the communion table, and considered the remoteness of the

communicants from scenes that were still dear to them, and how in their

homesteads in the woods, which swept to the horizon, they were as sheep

without a shepherd, he lifted up his voice and wept. He was thankful to

have witnessed such a sight, and his feeling was, “O that my father had

been with, us! What a welcome he would have received!” The great outcry

of the people was for ministers; and an old Doctor amused Mr. Macleod by

saying to him, “Wo don’t expect a very clever man, but would be quite

pleased to have one who could give us a plain every-day sermon, like

what you gave us yourself to-day.

Some months after his return from America Mr. Macleod attended meetings

in connection with the Evangelical Alliance. His soul was refreshed and

gladdened by communion with brethren, who, though known by different

names were one in Christian purpose. Writing to his sister from one of

the meetings, he said: “Bickersteth, dear man, is in the chair, and

Bunting, noble man, is now speaking. Angell James is about to follow,

and Dr. Raffles has finished. It is mere chat, like a nice family

circle, and I hope that our Elder Brother is in the midst of it.”

Ronge and Czersky, who had headed a revolt from Popery in Prussian

Poland and Silesia, having been at one of the meetings of the Alliance,

some of its members were anxious to obtain fuller information as to the

character of their work, and Mr. Macleod was requested to accompany Dr.

Herschell on a mission of inquiry to their principal congregations. They

found that the movement under Ronge had assumed a Rationalistic form,

and was little more than “a mixture of Socialism and Deism, gilded with

the morality of the Bible, and having a strong political tendency

towards communism*. They were better pleased with Czersky and his

people, who appeared to be simple, devout Christians. The interest of

their visit was heightened by interviews with Neander and other German

theologians, and they brought back some valuable facts in relation to

religious life on the Continent.

The same year Mr. Macleod gave practical proof of his brotherly feeling

for other denominations by preaching an anniversary sermon in the

Wesleyan chapel in Edinburgh. He was the first minister of the

Established Church to occupy that pulpit, and had the pleasure of

preaching to a congregation that crowded the aisles and pulpit stairs.

The death of his old teacher, Dr. Chalmers, in 1847, brought from him a

fine eulogium of the man “whose noble character, lofty enthusiasm, and

patriotic views will rear themselves before the eyes of posterity like

Alpine peaks, long after the narrow valleys which have for a brief

period divided us are lost in the far distance of past history!"

In 1848 he felt so severely the effect of overwork that he was compelled

to retire for a time from all public engagements. For change of air he

went to Shandon, a lovely spot slanting down to the placid waters of the

Gareloch, and was conscious of reviving health, as he wandered over the

heather, along the track of musical brooks, and by rocks having crevices

filled with ferns and primroses. His meditations were in harmony with

the scenes amid which he wandered, and the following passage only needs

“the accomplishment of verse” to be a true Wordsworthian poem:

“How many things are in the world yet not of it! The material world

itself, with all its scenes of grandeur and beauty, with all its gay

adornments of tree and flower and light and shade, with all its

accompanying glory of blue sky and fleecy cloud, or midnight splendour

of moon and stars—all are of the Father. And so too is all that inner

world, when, like the outer, it moves according to His will; of loyal

friendships, loving brotherhood; and the heavenly and blessed charities

of home, and all the real light and joy that dwell, as a very symbol of

His own presence, in the Holy of Holies of a renewed spirit. In one

word, all that is true and lovely and of good report— all that is one

with His will—is of the Father and not of the world. Let the world,

then, pass away with the lust thereof ! It is the passing away of death

and darkness— of all that is at enmity to God and man. All that is of

the Father shall remain for ever.”

In the beginning of 1851, Mr. Macleod experienced a great but not

unsanctified sorrow in the death of his beloved and saintly friend John

Mackintosh, who, after long and laborious preparation for the ministry

of the Free Church, became the victim of consumption. He died abroad,

but his body was brought to Scotland, and we have this record: “We

buried him on Wednesday last. The day was calm and beautiful. The sky

was blue with a few fleecy clouds. The birds were singing. Everything

seemed so holy and peaceful His coffin was accompanied by those who

loved him. As I paced beside him to his last resting-place, I felt a

holy joy as if marching beside a noble warrior receiving his final

honours. O, how harmonious seemed his life and death! I felt as if he

was still alive, as if he still whispered in my ear, and all he said—for

he seemed only to repeat his favourite sayings— was in beautiful keeping

with this last stage of his journey: ‘It is His own sweet will;’

‘Dearie, we must be as little children;’ ‘We must follow Christ., And so

he seemed to resign himself meekly to be borne to his grave, to smile

upon us all in love as he was lowered down; and as the earth covered him

from our sight it was as if he said, ‘ Father, thou hast appointed all

jn once to die. Thy sweet will be done ! I yield to thine appointment!

My Saviour has gone before me; as a little child I follow.’ ”Mr. Macleod

published a memoir of him entitled, “The Earnest Student.” The writing

of it was to him a labour of love, and as Mackintosh had been studying

for the ministry in the Free Church, he devoted the proceeds of the

book, £200, to the Foreign Missions of that Church. He was too effective

a preacher, and too successful in parish, work to he allowed to remain

long in the comparative obscurity of Dalkeith. In 1851 he became

minister of the Barony Church, Glasgow. In the same year he was married

to the sister of his beloved friend John Mackintosh, of Geddes. The

first house he occupied in Glasgow was so situated that from the front

he could look on the crowded masts that rose above the bridges and the

piers of the Clyde, and on the green declivities of the Cathkin Hills;

while from the back windows there was a glorious view of the familiar

steeps of Campsie Fell. The glow of sunrise or of sunset on these steeps

was such a delight to him that often when he had guests he made them

follow him up stairs to share his own enjoyment of the scene.” It was

his custom to rise early in the morning, so as to ensure some hours for

reading and writing before engaging in the more active duties of his

pastorate. With curtains drawn, gas lighted, and apparatus for making

coffee close at hand, he enjoyed the cosiness and quiet of his study,

and thought the sounds from the wakening city and the clash of a

thousand hammers on the boilers of steamers destined for the Atlantic

and Pacific Oceans more inspiring music than the songs of larks or the

bleating of sheep. In the employments of those early hours he often

found an impulse to greater earnestness in his ministerial calling: “How

my morning readings in Jonathan Edwards make me long for a revival! It

would be worth a hundred dead General Assemblies if we had any meeting

of believing ministers or people to cry to God for a revival. This, and

this alone, is what we want. Death reigns! God has His witnesses

everywhere, no doubt; but as a whole we are skin and bone. When I

picture to myself a living people, with love in their looks and

words,—calm, zealous, self - sacrificing, — seeking God’s glory and

having in Glasgow their citizenship in heaven; it might make me labour

and die for such a consummation!

The Barony Church stands near the cathedral, and is one of the

unsightliest ecclesiastical buildings in Scotland. But the man in the

pulpit gave to it a charm that was felt throughout Glasgow, and the

interest never abated. Since Chalmers thundered in the Tron church, no

preacher gained such influence over the citizens. His manner was

deliberate, and was rather conversational than oratorical; his thoughts

were not so much like masses of ore quarried out of difficult rocks, as

like flowers springing spontaneously from a genial soil; and his

sentences were usually short, simple, and incisive. He could not speak

for any length of time without throwing out an image or introducing a

few bright, poetic words; but there was no long sweep of rhetorical

splendour, and no premeditated climax. The impression he gave his

hearers was that he was a man of large human interests, and that he was

desirous above everything else that Christ should be magnified in their

lives, and that they should be able to rejoice in hope of immortality

and eternal glory. But he was far from thinking that when he left the

pulpit his work was done. His parish was wide and populous, and he

devised a number of schemes for its neglected districts. Systematic

visitation was carried on by himself and his people, schools were

multiplied and Mission churches were built.

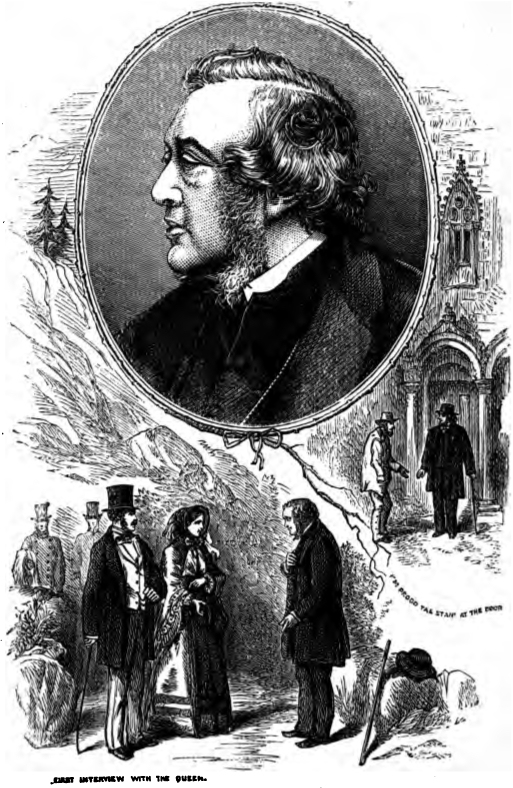

In October, 1854, Mr. Macleod preached for the first time before the

Royal Family in Crathie Church. He “preached with intense comfort, and

by God’s help felt how sublime a thing it was to be His ambassador.” In

the evening, after wandering through a green field, he sat in quiet

meditation on a block of granite, in the midst of beautiful scenery, and

under a calm, half golden sky. His reverie was disturbed by some one

asking him if he was the clergyman who had preached that day, and he was

noon in the presence of the Queen and the Prince Consort. Her Majesty

came forward, and in a kindly graceful manner, said, “We wish to thank

yon for your sermon;” and then inquired about his father, and his own

parish. Her Majesty has given a pleasing record of the service in her

“Journal,” speaking of the sermon as quite admirable: so simple, and yet

so eloquent, and so beautifully argued and put and of the prayer as

being very touching in its reference to the Royal children, and “the

dying, the wounded, the widow, and the orphans.” After that visit Mr.

Macleod was frequently at Balmoral, and was specially summoned to meet

Her Majesty there at the time when the shadow of her great sorrow was so

dark. Writing from Balmoral to Mrs. Macleod, he says, “You will return

thanks with me to our Father in heaven for His mercy and goodness in

having hitherto most surely guided me during this time, which I felt to

be a most solemn and important era in my life. All has passed well—that

is to say, God enabled me to speak in private and in public to the Queen

in such a way as seemed to me to be truth—the truth in God’s sight: that

which I believed she needed, though I felt it would be very trying to

her spirit to receive it. And what fills me with deepest thanksgiving is

that she has received it, and written to me such a kind, tender letter

of thanks for it, which shall be treasured in my heart whilst I live.”

He received the diploma of D.D. from the University of Glasgow in 1858,

but was rather saddened than elated by this honour, for he felt that it

stamped him with old age, and was a sign that he had but a short time to

work; and his prayer to God was that he might be able to brace every

nerve of his soul in endeavouring to glorify Him while on earth.

Notwithstanding his various activities, and the conspicuous place he

held before the public, he was always mindful of personal piety. It is

true his humour, his freedom in some doubtful matters, his occasional

departures from the strict lines of Scottish orthodoxy, were not

altogether favourable to his reputation for godliness; but those parts

of his journal in which his inner life is unfolded show that he was not

without experimental knowledge of the spiritual vitalities of

Christianity. Perfect holiness was one of the things he aimed at and

prayed for: “Is it possible that I shall habitually possess myself, and

exercise holy watchfulness over my words and temper, so that in private

and public I shall live as a man who truly realises God’s constant

presence—who is one with Christ, and therefore lives among men and acts

towards them with His mind and spirit? I, meek, humble, loving, ever by

my life drawing men to Christ?—self behind, Christ before! I believe

this to be as impossible by my own resolving, as that I could become a

Shakespeare, a Newton, a Milton; yet if God calls me to this, God can so

enable me to realise it that He shall be pleased with me. But will I

really strive after it? O, my Father! see, hear and help Thy weak and

perishing child! For Christ’s sake, put strength in me; fulfil in me the

good pleasure of Thy will. Lord, pity me and have mercy on me, that I

may famish and thirst for Thee and perfect holiness.”

The holy feelings Dr. Macleod cultivated in the retirement of the study,

urged him to more strenuous efforts for the evangelisation of the lapsed

classes in his parish; and in thinking how he could benefit them, he

decided, among other things, on holding services on Sunday evenings, to

which none were to be admitted but such as were in their working

clothes. Crowds gathered to the Barony Church, and men and women with

begrimed faces and uncombed heads were allowed free access to the

cushioned pews. As they sat there in their stained and ragged coats and

shawls, they suggested a striking contrast to the morning and afternoon

congregation, but their behaviour was as decorous as could be wished,

and though Bibles and Psalm-books were left out for their use, they were

never known to take any of them away.

The precentor at the services was a blind man; and bending over the

pulpit Dr. Macleod used to say, “You’ll rise now, Peter, and begin,” and

then Peter with the Psalms in raised type before him, traced the lines

with his fingers, giving out only two at a time, so that those who were

without books might be able to join in the singing. When a church was

built for working men a carter officiated as beadle. Dr. Macleod wished

him to stand at the door in his working clothes, but thought he might

not like to do so and said, “If you don’t like to do it, Tom, if you are

ashamed—” “Ashamed!” was the quick reply, “I’m mair ashamed o’ yoursel’,

Sir. Div’ ye think that I believe, as ye ken I do, that Jesus Christ,

Who died for me, was stripped o’ His raiment on the cross, and thatI—Na,

na, I’m proud tae stan’ at the door.” When Tom was dying of an

infectious disease his friends asked him if they should inform Dr.

Macleod, but he said, “There’s nae man leevin’ I like as I do him. I

know he wad come. But he shouldna come on account of his wife and bairns,

and so ye mann na’ tell him.”

The special services were productive of great good; hundreds were

reclaimed from vice, and many were converted and became members of the

church. Dr. Macleod’s joy was almost unbounded when he saw a number of

them seated at the Lord’s table. He might well be thankful to God, for

no higher honour could have come upon him than to have been instrumental

in hewing the rugged forms of humanity gathered from the foulest wynds

and closes of the city into the comeliness of Christian discipleship.

Nor were they unmindful of their indebtedness to his labours, for in an

address they presented to him they said: “Not content with bringing us,

as it were to the entrance of the Saviour’s Church, and leaving us to go

in or return as we pleased, you have led us into the great congregation

of His saints on earth, and have invited us to take our places among our

fellow-believers at the Lord’s table, so that we might enjoy similar

privileges with them. Those of us who have accepted this invitation,

have nothing of this world’s goods to offer you in return, but we shall

retain a life-long gratitude for your kindness—a gratitude which shall

be continued when we shall meet in that eternal world which lies beyond

the grave.”

In 1864, Dr. Macleod visited the Holy Land. He has given a graphic

description of the scenes and circumstances of his visit in the book

entitled “Eastward;” but in his private letters we have a fuller account

of his feelings of reverence and delight as he passed through the

valleys and over the hills on which “the glory and the consecration” of

the Saviour’s presence had fallen. One night when the stars were shining

with variegated splendour, and the large bright moon was pouring silvery

lustre on the foliage of the sycamores and palms, he left his companions

in their tents, and went to a ridge of hills from which he saw a village

on the opposite side of the valley. Writing to his sister, he said:

“You can understand my feelings better than I can describe them, when I

tell you that the village was Nazareth. And you can sympathise with me

when I say to you, that, after gazing awhile in almost breathless

silence, and thinking of Him Who had there lived, and laboured, and

preached; and seeing in the moonlight near me the well of the city to

which He and Mary had often come, and, farther of, the white precipice

over which they had threatened to cast Him; and then tracing in my mind

the histories connected with other marvellous scenes in His life, until

‘Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews’ died at Jerusalem, and all the

inexpressibly glorious results since that day which has made the name of

this place identical with the glory of the world; and when I thought of

all that I and others dear to me have received from Him, and from all He

was and did, yon will not wonder that I knelt down and poured out my

soul to God in praise and prayer. And in that prayer there mingled the

events of my past life, and all my friends whom I loved to mention by

name, and my dear father, and the old Highlands, the state of the

Church, and of the world, until I felt Christ so real, that had He

appeared and spoken it would not have seemed strange.”

Soon after his return from Palestine Dr. Macleod was appointed to the

Convenership of the India Mission of the Scotch Church. Referring to the

appointment he says: “I have accepted of this without doubt, though not

without solemn and prayerful consideration—for I have tried, at least

for the last twenty-five years, to accept of whatever work is offered to

me in God’s providence. I have, rightly or wrongly, always believed that

a man’s work is given to him—that it need not so much be sought as

accepted—that it is floated to one’s feet like the infant Moses to

Pharaoh’s daughter. Mission work has been a possession of my spirit ever

since I became a minister; I feel that God has long been educating me

for it. I go forth tolerably well informed as to facts, and loving the

work itself, with heart, soul and strength; I accept it from God, and

have perfect confidence in the power and grace of God to give us the men

and the money. Thank God for calling me in my advanced years to so

glorious and blessed a work.”

India had long been to him a land of great and varied interest. His

conversations with the widow of the Marquis of Hastings, in Loudoun, had

deepened his impression of the grand features of its scenery, and the

stirring incidents of its history; and he had a thorough acquaintance

with those achievements of war and statesmanship by which it had been

brought into subjection to British authority. Its scenes of shame and

glory were accurately pourtrayed on his mind: and while he mourned over

the error and wretchedness of its people, he had confidence in the

Gospel of Christ, as being able to draw them from their gorgeous yet

debasing idolatries, and to raise them to the dignity and magnificence

of “a royal priesthood,” rejoicing in the service of the Lord. There was

scarcely any sacrifice he was not prepared to make in the evangelisation

of India, and though his health seemed scarcely equal to the fatigue of

long travel and the debilitating influence of the hot climate, he set

sail for Bombay in 1867, accompanied by Dr. Watson of Dundee, to promote

the objects of the Mission.

While in India Dr. Macleod was almost incessantly engaged either in

public services or private investigations and interviews, but before he

had worked out his plan of operations, he was prostrated by sickness,

and after a hasty visit to Benares, Agra, Delhi and other noted cities,

embarked for home. He was met at Alexandria by Mrs. Macleod, and

returned to Scotland by Malta, Naples, Borne and Paris.

The General Assembly of 1869 unanimously elected Dr. Macleod to the

Moderatorship. This was the highest ecclesiastical honour that could be

awarded him, and was a fitting recognition of his great services in the

pulpit, and in the Home and Foreign Missions of the Church. Whatever

influence the office gave was used by him in the advocacy of schemes for

the enlargement of the Church, and especially of its Indian Mission. The

claims and necessities of the latter work were frequently urged by him

with all his power of argument and eloquence. India had taken hold of

his heart, and he went on pleading for funds and Missionaries, even when

in bodily suffering which he might justly have assigned as a reason for

perfect rest.

His health was so shattered that in 1872 he was compelled to give up his

Convenership. He made his final appeal for the Mission in a long and

memorable speech before the Assembly.

This was nearly the last scene of his public life. He preached once in

the Barony Church on the following Sabbath, taking for his text, “We

have forsaken all, and followed Thee; what shall we have therefore?” All

that he had written of the sermon was on a sheet of note paper; but from

a full heart he exhorted his hearers to accept the guidance of Christ,

assuring them that if they did so, they would at the last be able

cheerfully to give up life and all into His keeping. With that sermon

his work ended. The Monday was his sixtieth birthday, and he thus wrote

to his friend, Principal Shairp: “I am threescore years to-day! John,

dear, I cannot speak about myself. I am dumb with thoughts that cannot

be uttered.....As I feel time so rapidly passing, I take your hand, dear

old friend, with a firmer grip. I have many friends; few old ones ! O

that I loved my oldest and truest, my Father and Saviour, better! But

should I enter heaven as a forlorn ship, dismasted, and a mere log—it is

enough—for I will be repaired. But I have been a poor concern, and have

no peace but in God’s mercy to a miserable sinner.” He suffered severely

through the week, but was often engaged in audible or silent prayer.

Having heard of the birth of a nephew, he said, “I have been praying for

this little boy of Donald’s; that he may live to be a good man, and by

God’s grace be a minister in the Church of Christ—the grandest of all

callings.”

On Sunday morning, June 16th, he asked his wife to sit beside him, and

spoke to her freely of his joy and confidence in God, telling her to

write down what he said that his words might be a comfort to her in her

day of sorrow. Two of his daughters went to him to kiss him before going

to church. Taking the hand of one of them he said, "If I had strength, I

could tell you things would do you good through all your life. I am an

old man and have passed through many experiences, but now all is perfect

peace and perfect calm. I have glimpses of heaven that no tongue, or

pen, or words can describe. About an hour after, with a gentle sigh, his

soul escaped to heaven.

He was buried beside his father in the Campsie graveyard. Civic and

University dignitaries, ministers and members of numerous churches,

preceded or followed the hearse to the outskirts of the city; while

crowds of working people watched the procession as it passed along the

streets, and testified by their sorrowful faces how they loved and

lamented him who had been to them so true a friend, and whose labours

had tended so much to their social and religious improvement. At Campsie

the shops were closed, and the whole population united in paying respect

to the son of their former minister. As the coffin was about to be

lowered into the grave, three wreaths were placed upon it bearing

inscriptions showing that they were from Her Majesty and other members

of the Royal Family.

“The spot where he sleeps is a suggestive emblem of his life. On the one

side are the hum of business and the houses of toiling humanity; on the

other, green pastoral hills, and the silence of Highland solitudes. More

than one eye rested that day on the sunny slope where he had so lately

dreamt of building a home for his old age—more than one heart thanked

God for the more glorious mansion into which he had entered/1

Unqualified approval cannot be given to all Dr. Macleod’s opinions and

public movements, but he was a good and great man, intent on the honour

of Christ and the moral improvement of his fellow men. He presented a

fine combination of manly power with philanthropic Christian zeal. He

was, to quote the inscription on one of the two painted windows placed

by Her Majesty in Crathie Church as memorials of his ministry, “a man

eminent in the Church, honoured in the State, and in many lands greatly

beloved.” |