Many years before Walter

Scott wove the name of Ulya into his song as one of a “group of islets

gay tbat guard famed Staff a round,” an old man, who had long been

renowned among the islanders for his wisdom and integrity, was dying in

one of its cottages. He called his children to his bedside, and with

patriarchal authority said, “I have searched carefully through all the

traditions of our family, and I never could discover that there was a

dishonest man among our forefathers. If therefore any of you should take

to dishonest ways, it will not be because it runs in our blood. I leave

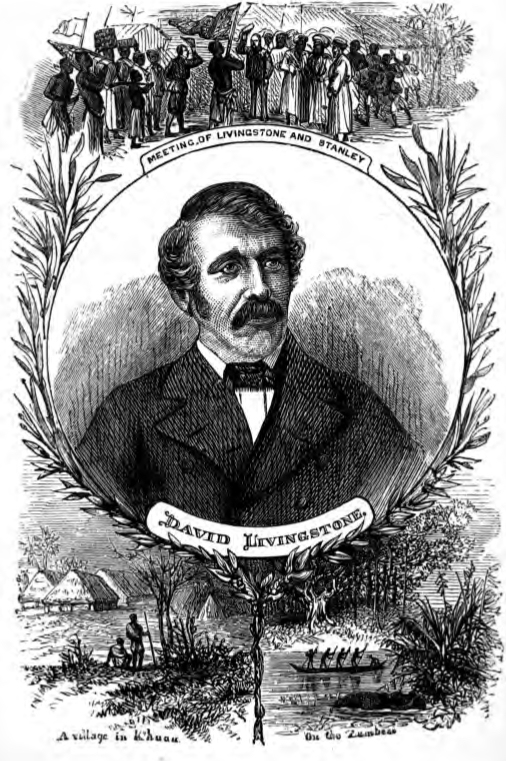

this precept with you: Be honest.” The old man was one of the ancestors

of David Livingstone, who regarded that dying charge as a nobler

inheritance for the family than a coat-of-arms quartered in gold and

crimson, or a castle enriched with baronial splendours. David’s

grandfather, being unable to obtain support for his numerous children

from his small farm in Ulva, removed to Blantyre, a village on a

beautiful reach of the Clyde above Glasgow, where he found employment in

a large cotton manufactory. In the noisier life of Blantyre he fondly

cherished the romantic memories of Ulva; and David, when a boy, listened

with delight to his Hebridean legends, and also to the Gaelic songs sung

by his grandmother, which she believed to have been composed by

islanders who had been captured by the Turks. The great traveller whose

name will be famous as long as Lake Ngami reddens with the glow of

African sunsets, or the Zambesi rushes down the awful chasm which breaks

its channel, was born at Blantyre in 1813. When ten years old he was

sent to the cotton-works; but was determined to make up for the defects

of his education by his own exertions, and with part of his first week’s

wages bought Ruddiman’s “Rudiments of Latin,” which he carefully

studied. He had to be in the factory, with short intervals for meals,

from six in the morning until eight at night, but as soon as his work

was over he hastened to a night-school, where he remained until ten, and

then, unless his mother snatched the book from his hand, sat reading and

thinking until twelve. His difficulties in the acquisition of learning

were great; but he was a thorough adept in the Scotch way of putting a

stout heart to a steep hill, and when sixteen was able to read Virgil

and Horace, and other classic authors. In English literature he

preferred books of Travel and Science to Boston’s “Fourfold State,” and

others of a like kind, to which his father wished him to give his

attention. The last time his father applied the rod to his shoulders,

was on his positively refusing to read Wilberforce’s “Practical

Christianity.” After a number of years his dislike of religious reading

was happily overcome by Dick’s “Philosophy of Religion,” and “Philosophy

of a Future State.” His parents had carefully instructed him in the

principles of Christianity, and about the time that Dr. Dick convinced

him that there was no real hostility between science and religion, he

began to feel the necessity of personal relationship to God through

Christ. The sense of sins forgiven awoke in him a desire to glorify his

Divine Benefactor, and his Missionary work in Africa was the outcome of

his happy experience of Christ’s saving power in Blantyre. When he

reached his nineteenth year he earned such wages as enabled him to

attend Greek and Medical classes in the Glasgow University through the

winter months, and also to take advantage of Dr. Wardlaw’s Divinity

Lectures in tlie summer. In his college course he did not receive, and

did not wish for, pecuniary help from any one; and, as day after day he

trod the nine miles of road between his home and Glasgow, he thought not

of the honours or emoluments of the scholar, but of greater capabilities

of doing good to his fellow men. Having finished his medical ,

curriculum, and passed an examination more than usually I severe, he was

admitted a Licentiate of Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons, and

rejoiced in becoming a member of a profession which has for its end the

mitigation of human suffering and the lengthening of human life.

It had been his intention to go as a medical Missionary to China, but

that field of Christian enterprise was closed against him by the

outbreak of the opium war, and he was induced by the London Missionary

Society to look towards Africa as the scene of his labours. He left

England in 1840, and landing at the Cape, went to Algoa Bay, and thence

to Kuruman, where the heroic Moffat had opened a paradise in the

wilderness. There was before him a fine exemplification of what could be

done by godly perseverance in the stone-built church and mission-house,

the printing press and the garden with the shadow of vine-leaves on its

herbs, and the fruit-trees blooming by its irrigating rivulet. Having

received instructions from the Directors of the London Missionary

Society to establish a mission further inland, he did not stay long at

Kuruman, but that station was always a bright spot to him, for when he

had been in Africa four years he was married to Mr. Moffat’s eldest

daughter, Mary. She had much of the spirit of her illustrious father,

and Livingstone had in her a helper with a brave affectionate soul, and

a hand never weary in good works. After some preliminary explorations,

he made choice of a part of the country occupied by the Bakatla tribe of

the Bechuanas, as the site of a mission station, and removed there in

1843. While at the village Mabotsa, his left arm was in part disabled by

a lion. He had shot it, but before the bullets took effect, it sprang

upon him, and would have killed him if a man whose life he had saved by

surgical skill when he was suffering from a wound inflicted by a

buffalo, had not come forward with his spear. The infuriated beast

turned its attention to its new assailant, and Livingstone was saved,

but had eleven teeth-marks in his arm, while the bone was so crunched

into splinters that it never properly united.

In 1845 Livingstone attached himself to the section of the Bechuanas

called the Bakwains. He thought highly of Sechele, the chief, a man of

bright intellect and impressible heart. When he opened his commission to

the people as a minister of Christ, Sechele asked him if his forefathers

knew of a future judgment. He replied in the affirmative, and began to

speak of the great white throne and the dead of all ages assembled

before the Judge. “You startle me,” replied the chief; “these words make

all my bones to shake; I have no more strength in me. But my fathers

were living at the same time yours were, and how is it that they did not

send them word about these things sooner? They all passed away into

darkness without knowing whither they were going.” Sechele was eager for

instruction, and soon learned to read the Bible. Isaiah was one of his

favourites, and he used to say, “He was a fine man, that Isaiah; he knew

how to speak.” He wished to aid the Missionary in his efforts to convert

his subjects to Christianity, but while as yet only in the twilight of

the faith, had little confidence in the efficacy of argument and

persuasion. “Do you imagine,” he asked, “these people will ever believe

by your merely talking to them;” and added, “I can make them do nothing

but by thrashing them; and if you like I shall call my head men, and

with our whips of rhinoceros-hide we will soon make them all believe

together.” When Sechele was baptized, and made a public profession of

Christianity, his people thought he was under the influence of some

strange glamour, and some of them addressed him in taunts, which, he

remarked, in the days of his heathenism would have cost them their

lives. A protracted drought rendered his position peculiarly trying, as

he had been a noted rain-maker, and the general opinion was that his

refusal to charm the clouds had caused the absence of rain. On account

of the drought the tribe migrated from Chonuane to the bank of a stream

called the Kolobeng. Livingstone built a house there, and when not

employed in teaching or preaching, had to act as gardener, carpenter and

blacksmith, while his noble wife, in addition to the mission work in

which she took part, made candles, soap, and the clothes required by the

family. A few words from Sechele suggested to Livingstone the expedition

to Lake Ngami. He was accompanied by Colonel Steele and Mr. Oswell, the

famous elephant hunter. The great difficulty was in crossing the

Kalahari Desert, which stretches between the lake and the Orange river.

The beds of ancient rivers show that it was once abundantly watered, but

now it has no running water, and very little in wells. Still it is not a

dreary waste of barren sand, but is almost covered with grass, and

plants with tuberous roots, and after a season of heavy rain produces

vast numbers of water-melons, with which both men and wild animals

rejoice to slake their thirst. Livingstone and his companions suffered

from want of water while they were in the desert; and at one time, when

terribly parched, thought they were about to dash into a lake, which, to

their chagrin, proved to be only a deceptive mirage caused by a blue

haze above the white incrustations of a huge salt-pan. Waves seemed to

dance before them, and trees to shadow their foliage in cool waters; and

so complete was the illusion that cattle, horses, dogs and Hottentots

rushed forward with the expectation of drinking to satiety. Two months

from the time of starting on their journey, Livingstone and his friends

were rewarded for the pains and perils they had undergone by seeing Lake

Ngami, the basin of which, though shallow, is about seventy-five miles

in circumference. But the Missionary, not content with the geographical

discovery, wished to reach Sebituane, the chief of the Makololo, who

lived two hundred miles beyond the lake. He was not at that time able to

extend his wanderings in that direction, and had to return to Kolo-beng.

Being still intent on the introduction of Christianity to Sebituane and

his people, he took his wife and children to the lake, and would have

passed over the intervening country, but the children were stricken by

fever, and he was compelled to abandon his purpose for that year. The

third attempt was successful, and he and his family received a generous

welcome from the chief. They had passed through a district infested by

the tsetse, a fly, the bite of which is fatal to most domestic animals,

and Sebituane, after expressing his joy at their arrival, said, “ Your

cattle are all bitten by the tsetse, and will certainly die; but never

mind: I have oxen, and will give you as many as you need.” In providing

for the present wants of his visitors, he gave them an ox and a jar of

honey, and prepared skins soft as cloth with which to cover themselves

at night. His life had been romantic as that of any hero honoured in

Scottish ballad or legend. He was at one time settled in the Bechuana

country, but being annoyed by hostile tribes, led his people over the

Kalahari Desert, and after adventures beyond the dreams of fiction,

crossed the Zambesi, overcame an immense army assembled to take the

skulls of his warriors as trophies, and established himself as ruler

over a wide tract of territory. His government was such as to conciliate

those who had been opposed to him, for he was as benevolent in peace as

heroic in war. When poor men went to his town with skins or oxen for

sale, he always spoke affably to them and fed them at his own cost.

Strangers, however large the party, never went away without each one

carrying a present from his hand, and the common verdict on him was, “He

has a heart! he is wise!”

Soon after Livingstone

entered his country, he was prostrated by inflammation of the lungs,

occasioned by an old wound. On the afternoon of the Sunday on which he

died, Livingstone, taking his little son with him, went to his house.

“Come near,” he said, “and see if I am any longer a man; I am done.” The

Missionary sat with him some time, and having commended his soul to the

mercy of Grod, was leaving, when he raised himself as much as he could,

and said to a servant, “Take Robert to Maunku (one of his wives) and

tell her to give him some milk.” These were the last words of the man of

whom Livingstone wrote: “He was decidedly the best specimen of a native

chief I ever met. I was never so much grieved by the loss of a black man

before; and it was impossible not to follow him in thought into the

other world, and to realise somewhat of the feelings of those who pray

for the dead. The dark question of what is to become of such as he must,

however, be left where we find it. *The Judge of all the earth will do

right!” The Makololo lived among swamps formed by the overflow of the

Chobe and the Zambesi. This rendered their country unhealthy for

Europeans, and Livingstone had to abandon his intention of settling

there with his family. There was no likelihood of his being able to

resume his labours at Kolobeng; for the Dutch Boers, who had become like

untaught Bechuanas in their barbarism, had broken up the mission station

in that place, and were evidently disposed to perpetuate their hostility

to missionary operations among the Bakwains. In those circumstances he

thought it best to embark his family for Europe, and to devote himself

to the task of exploring the country in search of a healthy district

which might be made the centre of evangelistic influences, and of

opening a path from the interior of the continent to its east or west

coast. After the death of Sebituane, the chieftainship devolved on his

daughter Mamochisane. She soon wearied of the office, and wished her

brother Sekelutu to take it. He hesitated, but at length yielded to her

earnest entreaties. Though he had not the abilities of his father he was

equally friendly to Livingstone, and readily aided him in his projects

for improving the condition of the Makololo.

In November, 1853, he set out on his daring expedition to Loanda, the

Portuguese settlement on the west coast. He took with him twenty-seven

men, two of whom were Makololo, and the rest belonging to different

tribes located on the Zambesi. His baggage consisted of a quantity of

beads, a little tea and sugar, about twenty pounds of coffee, books,

scientific instruments, a magic-lantern, and a tin canister containing a

change of clothes. Sekelutu accompanied the adventurers to the river

Chobe, on which they embarked in canoes, which were paddled in waters

swarming with hippopotami, and between banks on which magnificent trees

formed embowered retreats for elephants, buffalos, zebras, and

antelopes. From the Chobe they struck into the Leeambye, or upper part

of the Zambesi, and received generous treatment from the people in the

villages they passed, who presented them with oxen, butter, milk, and

meal. They rested on the Sabbath; and Livingstone recorded the following

of a Sabbath spent when they were on their way to the confluence of the

Leeba and Zambesi: “Rain had lately fallen, and the woods had put on

their gayest hue. Flowers of great beauty and curious forms, unlike

those in the south, grow everywhere. Many of the forest-trees have large

palmated leaves and trunks covered with lichens; and the abundance of

ferns which, appear in the woods, indicates a more humid climate than

any to the south of the Barotse valley. The ground swarms with insect

life; and in the cool mornings the welkin rings with the singing of

birds, whose notes, though less agreeable than those of the birds at

home, because less familiar, nevertheless strike the mind by their

loudness and variety as the wellings forth of praise to Him who fills

them with overflowing gladness. We all rose early to enjoy the balmy air

of the morning, and assembled for Divine worship; but amidst all the

beauty with which we were surrounded, a feeling of want was awakened in

my soul, at the sight of my poor companions, and at the sound of their

bitter, impure words, and I longed that their hearts might be brought

into harmony with the Great Father of Spirits. I pointed out to them in

the simplest words the remedy which God has presented to us in the

precious gift of His own Son, on Whom the Lord ‘ laid the iniquity of us

all.’

The great difficulty in

dealing with these people is to make the subject plain. The minds of the

auditors cannot be understood by one who has not mingled much with them.

They readily pray for the forgiveness of sins, and then sin again;

confess the evil of it, and there the matter ends.” A tall stalwart

young woman named Manenko, who was chief of one of the villages on the

Leeba, while favouring the objects of the expedition, insisted on

Livingstone and his companions leaving the canoes and proceeding by

land. She seized the luggage, and the black men, frightened by her sharp

tongue, readily succumbed, but Livingstone manifested a determination to

go on in his own way. Seeing this, she laid her hand on his shoulder,

and with a motherly look, said, “Now, my little man, just do as the rest

have done.” He had to yield, and rode on ox-back, while she, with her

husband and a noisy drummer, walked towards the residence of her uncle

Shinte, who received the white man with all the ceremony of an African

court, but soon slided from his dignity to encouraging friendliness.

After leaving Shinte, Livingstone had to contend with difficulties that

would have overcome a man of less indomitable mind. He was often

enfeebled by fever, his men at times became dispirited, greedy or

suspicions tribes threatened the party with deadly attacks, flooded

plains and wide rivers had to be crossed, and scarcity of provisions was

painfully felt. But through all he held to his purpose, and, on the 31st

of May, 1864, was welcomed to Loanda by Mr. Gabriel, an English

gentleman, who was residing there as a commissioner for the suppression

of the slave-trade. The sea was viewed with astonishment by his simple

followers, who, in afterwards relating their adventures, remarked: “We

were marching along with our father, believing that what the ancients

had always told us was true, that the world has no end; but all at once

the world said to us, ‘I am finished, there is no more of me.’

”Livingstone’s health was so affected by repeated attacks of fever that

he had to stay a considerable time at Loanda. He might have gone to St.

Helena, or have come to England on one of the ships of the British navy,

but he felt it his duty to restore his people to their homes, and when

convalescent started for Linyanti, the Makololo capital. The route

homeward was in part varied from that of the journey to the coast, but

the incidents of travel were similar. The travellers were

enthusiastically welcomed by their friends who had scarcely expected

seeing them again, and a grand meeting was convened in Linyanti to

inspect the articles which had been brought from Loanda, and to hear the

report of the wonders which had been seen. During his stay in the town,

Livingstone was fully employed, for all of its inhabitants, to the

number of seven thousand, thought themselves free to call on him, and he

prescribed for their ailments, or endeavoured to engage them in

conversation on the facts and doctrines of Christianity. He also held

frequent meetings for public worship, and noticed greater decorum of

behaviour on the part of the people than when he first went among them.

Though remote from

civilisation and uncheered by the presence of his wife and children, yet

standing before the swarthy sons of the Zambesi, and telling them of the

love of their Heavenly Father in sending His Son to redeem them from

their guilt and misery, he knew a sublimer joy, and held a higher

position than any of those Pharaohs who were borne in golden galleys

among the lotus-flowers of the Nile, or sat enthroned amid the pictorial

pride of Egyptian palaces. Having found that the path to the west would

not be serviceable to the Makololo, Livingstone resolved to work his way

to the east coast by the Zambesi. Seke-letu aided him largely in

preparing for the journey, and was anxious that he should bring back

Ma-Robert, as Mrs. Livingstone was called; it being the custom of the

Makololo to designate the mother by the name of the eldest child. On his

departure Mamire, who had married the mother of Sekeletu, said to him:

“You are now going among people who cannot be trusted because we have

used them badly; but you go with a different message from any they ever

heard before, and Jesus will be with you, and help you, though among

enemies; and if He carries you safely and brings you and Ma-Robert back

again, I shall say He has bestowed a great favour upon me. May we obtain

a path whereby we may visit, and be visited by other tribes, and by

white men!” Livingstone had not proceeded very far before he saw the

five gigantic columns of vapour which betokened his approach to the

great falls of the Zambesi.

The scenery of the river

above the falls has a calm beauty, in wide contrast to their terrible

grandeur. Lovely islands, like costly vases filled with choicest

vegetation, dot the waters, and on either side the banks rising in green

acclivities, are shadowed by the vast trunks of baobabs and groups of

graceful palms, while the silvery mohonono glimmers amid the darker

green, and trees resembling the elm and the chestnut remind the

traveller of the boughs that knit themselves into sylvan arches above

English lawns. The river, between five and six hundred yards wide when

Livingstone saw it, but a thousand yards when in full flood, is

precipitated into a black fissure that runs across its bed, and held for

thirty miles in a narrow chasm in the basaltic rock. Some of the

natives, taking advantage of the eddies and still pools, cautiously

paddled him in a canoe to an island in the middle of the river, and on

the very edge of the fearful crevice. Looking down on the right of the

island he could see nothing but a dense cloud of spray, on which two

rainbows shed their prismatic light; but on the left of the island he

saw the water a hundred feet below him rolling away in a white impetuous

mass. The Makololo called the falls, Mosi-oa-tunya, or

Smoke-sounds-there, but Livingstone named them the “Victoria Falls.”

Many honours have been

worthily bestowed on the Queen of England, but in no part of the world

is her name associated with a more magnificent display of the Creator’s

power than that on the distant Zambesi. With a hundred and fourteen men

carrying tusks for barter, Livingstone went on his way towards Kilimane

on the East Coast. When they got beyond the dominions of Sekeletu, they

felt some anxiety as to the manner in which they would be received by a

tribe whom the Makololo regarded as being in rebellion against their

chief. The people of one village seemed disposed to be friendly, but

those of another made hostile demonstrations. They began by attempting

to spear a young man who had gone for water. Failing in that, they

approached the travellers, and one of them, howling like a maniac and

with eyes protruding and foaming lips, stood close to Livingstone,

brandishing a small battle-axe with a fierceness which was anything but

soothing to the nerves. Livingstone felt some alarm, but disguised it

from the spectators, and would not allow his own men to knock the savage

on the head as they wished to do. When his courage had been sufficiently

tested, he beckoned to one of the friendly villagers to lead the madman

away, and was glad to see the battle-axe at a safe distance.

The Makololo and their

leader were threatened with destruction. “They are lost,” it was said.

“They have wandered in order to be destroyed.” But one of their friends

did them good service by explaining their character and intentions, and

they escaped without molestation. From a range of hills near the

confluence of the Kafue and the Zambesi, Livingstone beheld a scene

which repaid him for many of the hardships and dangers of his journey.

“At a short distance below us,” he wrote, “ we saw the Kafue, wending

its way over a forest-clad plain to the confluence, while in the

background, on the other side of the Zambesi, lay a long range of dark

hills, with a line of fleecy clouds overhanging the course of the river

at their base. The plain below us, at the left of the Kafue, had more

large game on it than anywhere else I have seen in Africa. Hundreds of

buffaloes and zebras grazed on the open spaces, and beneath the trees

stood lordly elephants feeding majestically. The number of animals was

quite astonishing, and made me think that I could here realise an image

of that time when Megatheria fed undisturbed in the primeval forests.”

Livingstone wished to cross the Zambesi near the village of a chief

named Mpende, but the people of the' village instead of manifesting

willingness to help the party, prepared to attack it.

Armed men were seen

gathering from all quarters, and spies frequently approached the

Makololo encampment. To two of these, Livingstone handed the leg of an

ox, desiring them to take it to Mpende, who on receiving it sent two old

men to enquire who the donor was. “I am a Lekoa,” (an Englishman) was

the reply. When they found he was not a Mozunga, as they called the

Portuguese with whom they had been fighting, they said, “Ah! you must be

one of the tribe that loves the black men.” They returned to Mpende, who

decided to grant a passage to the white man and his followers, and had

them ferried across the river in canoes. After various experiences they

reached Kilimane on the 20th of May, 1856. Livingstone had been engaged

in explorations for the greater part of four years. His work was sublime

in its magnitude and purpose; he had passed from side to side of the

African continent, had sailed on rivers in which no white man’s face had

been before reflected, and travelled through forests in which there had

never before been the track of a white man’s footsteps; he had for ever

dispelled the old fancy that the interior of Africa was a desert in

which it would be vain to look for water or foliage, by ascertaining the

abundance of its streams and the fertility of its soil; and he had done

this, not that his name might be great before the world, that he might

be renowned in the poet’s lay and the orator’s period, or that he might

lift the brow darkened by the African sun before applauding multitudes

in the halls of science and literature ; but to demonstrate the grandeur

of the field open to the Christian Missionary, to facilitate the

intercourse of tribe with tribe, to give to lands wasted and depopulated

by war the aspect of a continuous garden, and to supersede the

abominations of slavery by a legitimate commerce.

Promising to return and

take back his men to Sekeletu, he embarked on H. M. brig Frolic, and

landed in England on the 12th of December, 1856. Great enthusiasm was

excited by his appearance in England and Scotland. The gold medal of the

Royal Geographical Society was awarded to him; Universities vied with

each other in conferring npon him their proudest diplomas; and the press

eulogised him in its most laudatory strains. But whatever pleasure the

applause of the nation might afford him, it was nothing to the pleasure

he would have had in sitting by the fireside in the old cottage of

Blantyre, and relating his African adventures to his venerable father.

It was with deep sorrow he learned that his aged parent had passed away

while he was in the interior of Africa, hut, on his way to his native

land. Having published thejbpok in which he described his adventures and

discoveries1 he was ready for another expedition in Africa, and Eord

Palmerston, then at the head of Her Majesty’s Government, consented to

assist him in further researches on the Zambesi, and in other parts of

Africa. He went out in 1858, with a party including his brother Charles,

and Dr. Kirk. They had a steam launch named the Ma-Robert in which to

navigate the rivers, and one of their earlier exploits was to pass up

the Shir6, one of the tributaries of the Zambesi, until they reached the

magnificent cataracts to which they gave the name of the illustrious

geographer Murchison.

Going overland from the

Shire, they discovered the lakes Shirwa and Nyassa, and near the latter,

a fine sheet of water about two hundred miles in length, were hospitably

entertained by an old man in the “ pillared shade” of a fine

banyan-tree, and were thankful to have a night of undisturbed rest in

that natural palace. But Livingstone did not forget his promise to the

men who had marched with him from Linyanti to the coast. They had stayed

during his absence at a Portuguese village, where they had maintained

themselves by cutting firewood, and by other employments, but were

impatient for his return and welcomed him back as their true and loving

father. Some of them were about to embrace him as he stepped from the

boat to the bank of the river, but others noticing that he was very

different in appearance from what he was when plunging with them through

morasses and struggling through tangled woods, cried out, “Don’t touch

him, you will spoil his new clothes.” The party started for Linyanti on

the 15th of May, 1860. It was a toilsome journey, but there was an

unceasing interest for the European travellers in the scenery of the

hills, the rich diversity of vegetable and animal life, and the strange

customs of the tribes with which they came in contact. When they halted

for the night fires were kindled, long grass was cut for beds, and

though they had no tent, they found it pleasant to look between the

branches above them to the large glories of the African sky.

he Makololo country was

safely reached, but it was not in such a prosperous condition as when

Livingstone left it in 1855. Drought had caused scarcity of food, and

Sekeletu had been attacked by leprosy. He had secluded himself in a

covered waggon which was enclosed in a fence of reeds, and allowed no

one to see him but his uncle and a noted female doctor. An exception,

however, was made in favour of Livingstone, who prescribed for him, and

relieved him so much that he began to have hopes of recovery. But the

disease, though checked, renewed its ravages, and on his death the

nation, founded by the genius of Sebi-tuane, was broken up by civil war.

Having looked for the last time down the awful rift of the Victoria

Falls, Livingstone and his party descended the navigable reaches of the

Zambesi in canoes, and re-embarked on. the Ma-Robert, which they had

left in charge of two English sailors, at a small island named Kanyimbe.

They steamed to the Kongone mouth of the Zambesi, where they abandoned

the Ma-Robert, which had become all but useless, for the Pioneer,

another vessel provided by the British government in which they were

ordered to explore the Rovuma, a river beyond the Portuguese dominion.

The dismal mangroves on the coast, and along, the lower parts of the

river were left behind, and they passed between beautiful ranges of

wooded hills, but when they had advanced about thirty miles the water

fell so rapidly, that it was necessary for them to return to avoid

waiting for the rains of another year.

Bishop Mackenzie, with

the agents of the Oxford and Cambridge Mission, having arrived the same

time as the Pioneer, Livingstone agreed to assist them in the search for

a suitable settlement on the highlands above the valley of the Shire. At

one point of the journey a long line of manacled men, women, and

children, came in sight, and with them a number of black drivers,

arrayed in grotesque finery, carrying muskets and assuming consequential

airs. There was a sudden collapse of their dignity when they saw the

faces of the English, and they rushed with all possible speed into the

forest. The captives were in a state of joyful amazement when their

bonds were severed, and they were told to cook and eat the provisions

they had been carrying for their drivers. One little boy said, “The

others tied and starved us, you cut the ropes and tell us to eat; what

sort of people are you ? Where did you come from ? ” Cruelty had not

been restrained even by self-interest, and two of the women in the

slave-gang had been shot for attempting to unfasten the thongs with

which they were bound; another woman’s child had its brains knocked out

because she was unable to carry her load with it at her back, and a man

falling down from fatigue had his head cloven by an axe. When

Livingstone had given what help he could to the bishop, he had a boat

carried to Lake Nyassa, and with his brother and Dr. Kirk made

researches on its waters and among the villages on its beach.

Getting back to the

Pioneer in a weak condition from want of food, they dropped down the

Shire, and anchored at the Great Luabo mouth of the Zambesi. They were

soon employed in the pleasant task of towing in the brig which had

brought Mrs. Livingstone, and the sections of the steamer which

Livingstone had ordered at his own cost for river navigation. The new

vessel, named the Lady Nyassa, was put together at Shapunga, and while

there Mrs. Livingstone was prostrated by fever. Medical aid proved

unavailing, and she died while the sunset of a Sabbath evening was

irradiating the waters and filling the woods with golden glory. A coffin

was made in the night, and the following day Livingstone saw the bright

flower of Kuruman, his beloved Ma-Robert, buried under the branches of a

great baobab tree. Though his heart was crushed by grief, he held

bravely to his work, and organised a boating expedition up the Rovuma.

He was away a month, and when he came back to the Zambesi found that the

waters had risen sufficiently in the Shir6 to allow the passage of the

Lady Nyassa.

The population had been

swept from the valley of the river by slave-agents, and in the record of

the voyage it is said: “ It made the heart ache to see the widespread

desolation: the river-banks once so populous, all silent; the villages

burned down, and an oppressive stillness reigning where formerly crowds

of eager sellers appeared with the various products of their industry.,,

The river swarmed with crocodiles, and in one place sixty-seven were

counted on the bank. Livingstone and his friends thought that if they

could get their vessel on Lake Nyassa they would be able to limit the

depredations of the men-stealers from the coast, and began to make a

road from the cataracts, on which to carry the Lady Nyaxsa in sections.

The difficulties were great as both labourers and provisions were

scarce, and before they could accomplish their object they were recalled

by Lord John Russell. H. M. ship Ariel took the Lady Nyassa in tow to

Mozambique, and Livingstone, with a small crew, navigated her thence to

Bombay, a distance of two thousand five hundred miles. He then embarked

for England, and reached London on July 20th, 1864. Mr. Webb, who had

been a daring and successful hunter, entertained him with generous

hospitality at Newstead Abbey; and where Byron had flashed in the

splendours of a great but perverted genius, he transcribed for the press

his own and his brother’s journals of their African experiences.

He was anxious to solve a

number of problems relating to the water-system of Africa, and to repeat

his efforts for the suppression of the slave-trade. The Royal

Geographical Society seconded his purpose, and the Government appointed

him to act as Her Majesiy’s consul to the tribes of the interior. His

expedition was attended by many trying circumstances: most of his men

deserted him, and some of them affirmed that he had been murdered. The

statement was happily proved to be false; but mystery again enshrouded

him, until he was found by the young American, Stanley, at Ujiji, on

Lake Tanganyika. He was then all but destitute, wearied in body and

depressed in mind, but hope revived in him as he saw the American

colours gleaming amid the foliage; and the cheery voice of Stanley made

him feel young again. Stanley urged him to return home, but he said,

“No; I should bike to see my family very much indeed. My children’s

letters affect me intensely, but I must not go home; I must finish my

task.” He wished to complete his survey of the sources of the Nile, but

his strength failed, and at length he became so weak that he had to be

carried on a native bedstead.

His faithful negro men

built a hut for him at a place called Hala, and beneath its grassy roof,

while kneeling as if in prayer, his soul went up from the Africa he

loved so well to be for evermore in the presence of the Saviour Whom he

had striven to honour in all the movements of his busy and adventurous

life. The dead body, after being dried in the sun, was put in a cylinder

formed of bark, and over the whole a piece of sail-cloth was sewn. Then

the men started with their precious burden for the coast, carrying with

them also the “ Last Journals ” of the great traveller, who, when

writing-paper and ink failed, made use of sheets of old newspaper and

the juice of a tree in recording his observations. Zanzibar was reached

after many adventures, and the body was put on board a ship bound for

England. The general feeling was that Livingstone’s dust should mingle

with that of the illustrious dead in Westminster Abbey.

A grave was opened in

that august and venerable sanctuary, and in the presence of a large and

distinguished company, the coffin was lowered into it. Members of both

Houses of Parliament, and of the great scientific institutions of the

country, men of renown in literature, in philanthropy and religion,

assembled to do honour to the memory of the man who had once been an

operative in the Blantyre factory; but the scene owed much of what was

sublime in it to the venerable head of Robert Moffat and the black face

of Jacob Wainwright, who had watched tenderly over his dying master at

Ilala. The brazen plate on the coffin bore the following simple

inscription:

DAVID LIVINGSTONE.

BORN AT BLANTYRE, LANARKSHIRE, SCOTLAND,

DIED AT ILALA, CENTRAL AFRICA.

4th May, 1873. |