GENIUS involves its

possessor in increased danger as well as increased responsibility. The

height to which a man of great intellectual powers may aspire is the

measure of the depth to which he may fall. He has in himself the

possibility of conspicuous glory, and also of conspicuous ruin. Without

moral restraint, superior mental gifts are developed in forms of more

gigantic wickedness. The flame which might have irradiated a nation with

beneficent light becomes an illumination for the orgies of vice. Genius,

even in a godly man, will lead to disastrous errors if not accompanied

by prudence. Sails may be unfurled and pennons rolled out, but if

discretion be wanting, there will be sad submergence or fatal crash on

the rocks. Edward Irving had princely endowments, but through defect of

judgment he fell into mournful eccentricities of speech and action. By

his fine bodily presence, his majestic voice, his elevated sweep of

thought, his language, gorgeous as a calm sea when it has caught the

hues of sunset, he was able to take a foremost place among the preachers

of his time; but he was without the “wisdom” that is “profitable to

direct,” and deviated into lines of conduct in which he found misery and

abasement.

He was born in the year 1792, at Annan, a little town on the Solway

Frith. Some of his relatives on his mother’s side obtained a local

renown by their peculiarities. One of his uncles published an

autobiography in the form of a tombstone; for, apprehensive that

posterity wonld not do justice to his achievements, one of which was a

lawsuit with his brothers and another the building of a bridge, he had

the stone inscribed with them and set up in the graveyard while he yet

lived. Another uncle was a man of Samson-like strength. Being once

annoyed by a number of men when he was on a visit to Liverpool, he

snatched up the poker, and twisted it, as if it had been but a green

sapling, around the neck of one of his assailants, who had to get a

blacksmith to take off the uncomfortable cravat. The first school that

Edward attended was kept by an old dame named Peggy Paine, a relative of

the notorious Thomas Paine. From Peggy, with her alphabet and words of

one syllable, he was transferred to a more important school kept by Mr.

Adam Hope, who had also the honour of numbering Thomas Carlyle among his

pupils. The future preacher was more intent on splashing among the waves

of the Frith, exploring glens and climbing hills, than on applying

himself to his school-books; yet he evidenced considerable interest in

mathematics, and hailed as a kind of holiday the day on which the master

taught that branch of science. The time spent in wild rambles over his

native country was. not altogether wasted. His early intimacy with

natural objects,—the tangled copses, the lonely uplands, the waters

dashing their foam at his feet, the sky with clouds floating like golden

argosies, or shadowed by the dark sweep of the thunderstorm,—was an

important element in his education. The pleasure he then found in the

aspects of the outer world influenced him through life, and even in the

dingy streets of London he was able to renew in fancy the Arcadian

charms which 'expanded and gladdened his boyish heart.

His out-door exploits were on one occasion nearly brought to a sudden

end. He and his brother John were in the sands of the Frith; the tide

rushed in and out with great fury, but the beach, with its glistening

pools, its seaweed and shells, bad so captivated them that they became

unmindful of the swift and stealthy waves. Happily a horseman came

galloping along, snatched up the lads, and rushed at full speed, not

knowing who they were, until he got to a place of safety, when he found

that they were his own nephews. A little longer and the voice that was

to make music grand as that of golden organ-pipes would have been

silenced by the impetuous surges. When thirteen years old, Edward was

sent to the University of Edinburgh. He lodged with his brother on a

lofty flat in one of the many-storied houses of the city. The lads were

left very much to their own devices in the matter of housekeeping, and

had to make their bed and cook their food; the latter not a very

difficult operation, as their diet consisted principally of the national

oatmeal, with its variations of cake, porridge and brochan.

In college as in school, Edward’s predilection for mathematics was

manifest; but his mental development owed most to his careful study of

the great masters of British literature. His soul grew larger by contact

with their stately thoughts and imagery, and at a later time, when the

antique splendours of his diction were assailed by a cold and narrow

criticism, be thus nobly vindicated himself:—“I fear not to confess that

Hooker and Taylor and Baxter in theology, Bacon and Newton and Locke in

philosophy, have been my companions, as Shakespeare and Spenser and

Milton have been in poetry. I cannot learn to think as they have done,

which is the gift of God; but I can teach myself to think as

disinterestedly, and to express as honestly what I think and feel; which

I have in the strength of God endeavoured to do. They are my models of

men, of Englishmen, of authors. My conscience could find none so worthy,

and the world bath acknowledged none worthier. They were the fountains

of my English idiom; they taught me forms for expressing my feelings;

they showed me the construction of sentences and the majestic flow of

continuous discourse. I perceived a sweetness in every thought, and a

harmony in joining thought to thought; and through the whole there ran a

strain of melodious feeling which ravished the soul as a vocal melody

ravisheth the ear.”

Irving attended classes four or five years in Edinburgh, and was then

employed as a school-teacher, but still went to Edinburgh at intervals

as a Divinity student. About this time he began a friendship with a man

who has outlived him many years, has thrown his rugged power into

numerous books, has severed himself from the faith in which Irving found

his joy and glory, and in his old age makes no sign of hope for himself,

and seems to have no hope for the world but in its subjugation by

red-handed despots. The reference is to Thomas Carlyle, who after

Irving’s death thus wrote of him: “One who knew him well,” meaning

himself, “and may with good cause love him, has said, ‘But for Irving, I

had never known what the communion of man with man means. His was the

freest, brotherliest, bravest human soul mine ever came in contact with:

I call him, on the whole, the best man I have ever, after trial enough,

found in this world, or now hope to find. The first time I saw Irving

was six and twenty years ago, in his native town, Annan. He was fresh

from Edinburgh, with college prizes, high character and promise. We had

come to see our schoolmaster, who had also been his; we heard of famed

professors, of high matters, classical, mathematical, a whole wonderland

of knowledge; nothing but joy, health, hopefulness without end, looked

out from the blooming young man."

We can scarcely help wishing that we had a record of one of those Nodes

Ambrosianoa in that secluded, wave-dashed Annan. There, while the

breakers moan, on the sands, and Orion shines grandly above the Frith,

and the lamp burns on the table, and the old clock in the corner sounds

the swiftly-gliding hours, what glowing, eloquent and poetic discourse

from the youth destined to pour a new light on the pulpit, and what

intensity of interest in the youth who has since wielded the pen with

surpassing, but often misdirected power! Irving was only eighteen years

old when he became master of a school in Haddington, and had scholars

nearly as old as himself. His government of the school was severe and

imperious, and he let the biggest lads know, by unmistakable sensations

on their backs, that he was dominie or lord; but out of school he walked

and talked and sported with the scholars in a manner that won their

affection and esteem. While he was in Haddington, Thomas Chalmers, who

was just beginning to shake Scotland with the thunders of his stormy yet

magnificent eloquence, was announced to preach in Edinburgh. The

schoolmaster and a number of his pupils went to hear him, starting after

school-hours and returning the same evening, walking altogether

thirty-five miles for the sake of a single sermon! When they got to the

church, they went up to the gallery, and were going into an empty pew,

when a man told them it was engaged, at the same time stretching his arm

across to prevent their entering. Irving reasoned with him, but in vain,

and his patience exhausted, he raised his hand and exclaimed, “Remove

your arm, or I will shatter it in pieces." The man was awed by Irving’s

manner, took away his arm, and the wearied lads followed their master

into the pew.

Irving was two years in Haddington, and then accepted the charge of a

school in Kirkcaldy, where, as in his previous school, he was unsparing

in the use of the rod. One day, when rueful sounds were coming out of

the room, a joiner appeared at the door, axe in hand, and asked, “Do ye

want a hand the day, Mr. Irving?” ironically intimating that he was able

to supplement the birch with a more effective weapon.

But if stripes were frequent in school, kindnesses were equally frequent

out of school. He taught the boys to swim in the Frith of Forth, not

seldom gliding through the water with a lesser one on his shoulders, and

at night took them out for astronomical observations. Once when they

were busy with a telescope, meteors darted from the sky, and some of the

townspeople imagined that Irving was drawing the stars down, or at least

knew when they would fall.

In 1815 he was licensed to preach by the Presbytery of Kirkcaldy, and

occasionally occupied the pulpit of that town, but was not much

appreciated, for the people said he had “ower muckle gran’ner.” One man

kicked open his pew door and stalked indignantly out of the church when

he saw the tall schoolmaster in the pulpit.

The first time he preached in Annan there was a large congregation,

drawn by curiosity to hear the youth so well known there as a boy. He

was reading his sermon when he raised the Bible too high, and his

manuscript fell over into the precentor’s desk. It was an exciting

moment to the congregation. What would the preacher do without his

paper? He leaned over the front of the pulpit, laid hold of the fallen

leaves, crushed them up in his hand, and went on as fluently as before.

The people were proud of a townsman who could thus assert his

independence of paper.

He stayed seven years in Kirkcaldy and left in the year 1818, being then

in the twenty-sixth year of his age. After waiting in vain for a call to

a church, he began to prepare for a mission to Persia. He would leave

the land of his nativity, the Frith shores, the banks and braes by which

the burns and rivers winded on their romantic way, the heathery moors,

the fir-crowned ledges, the snowy scalps of the ancient mountains, the

green retirements of the woods, the lochs dimpled by the Highland

breeze, the towns and hamlets so dear to him; and in Ispahan and

Astrabad, and where Persepolis once stood the queen of the East, he

would preach the everlasting Gospel. He would go not as the agent of any

society, but strike out boldly and alone, like one of the primitive

evangelists, and he would roll out his commission and announce a Saviour

in regions covered with darkness and the shadow of death. Irving’s

project never got beyond the region of dreams, but more than twenty

years since we saw the magnanimous daring with which he meditated his

Persian scheme worked into fact by the Methodist youth who went from

Yorkshire to China on his own responsibility, to grapple with the

heathenism of that huge empire.

While Irving was looking across to Asia as the scene of his future

movements, he was invited by Mr. A. Thomson to preach in St. George’s,

Edinburgh, at the same time receiving an intimation that Mr. Chalmers

would be present, that he was looking out for an assistant, and might

make choice of him. After some waiting he had an interview with Mr.

Chalmers, and the conclusion was, “I will preach to your people if you

think fit, and if they bear with my preaching they will be the first

people who have borne with it.” He was diligent in his visitation of the

Doctor’s parishioners, and when he entered a house, no matter how mean

or poor it might be, he began with the salutation, “Peace be to this

house,” and ere he left he laid his hands on the head of each child of

the family, and said in tender and affectionate tones, “The Lord bless

thee, and keep thee.” But though he won his way to the hearts of the

poor, it was not easy to content those who could only see excellence in

Chalmers, and when it was discovered that he was to preach, numbers left

the church with disappointment on their faces, saying, “It’s no himsel’

the day.”

Irving was quite as wonderful in his own way as the great “himsel',” but

it was not then the fashion to admire him; his name was still in

obscurity, and not, as it became, a charm to draw multitudes together.

Besides, to say nothing of the power which Chalmers found in a direct

and faithful evangelicism, he was better fitted to gain immediate

popularity than Irving. Chalmers at once stormed his way to the hearts

and electrified the souls of his hearers; Irving appealed by the slower

processes of argument and reason to the intellect of the congregation.

Chalmers’ discourses had the quality of suddenness and startling

grandeur, resembling avalanches thundering down an Alpine precipice ;

Irving’s discourses were characterised by a less tumultuous yet broader

magnificence, and might be likened to a stately river sweeping through a

luxuriant valley, and reflecting the grim masonry of lone keeps and the

pinnacles of great cities.

Irving was unappreciated in Glasgow save by a comparative few; but the

day was at hand when his genius was to assert itself, and when, so far

as popular effect is concerned, he was to win some of the greatest

pulpit triumphs ever known. Before leaving Glasgow for the charge he had

accepted in London, he preached a farewell sermon, in which he thus

beautifully expressed himself, “God alone doth know my destiny, but

though it were to minister in the hall of nobles and the courts and

palaces of kings, He can never find for me more natural welcome, more

kindly entertainment, and more refined enjoyment than He hath honoured

me with in this suburb parish of a manufacturing city. My theology was

never at fault around the fires of the poor; my manner never

misrepresented, my good intentions never mistaken. Churchmen and

Dissenters, Catholics and Protestants, received me with equal

graciousness. Here was the popularity worth the having, whose evidences

are not in noise, ostentation and numbers, but in the heart opened and

disburdened, in the cordial welcome of your poorest exhortations, in the

spirit blessed by your most unworthy prayer, in the flowing tear, the

confided secret, the parting grasp, and the long, long entreaty to

return. Of this popularity I am covetous, and God in His goodness hath

granted it in abundance, with which I desire to be content."

He began his labours in the Caledonian Chapel, London, one Sabbath

morning in the year 1822. His first text was, “Therefore came I unto you

without gainsaying, as soon as I was sent for: I ask therefore for what

intent ye have sent for me?” Crowds were soon drawn to the mean building

by the melodious strain sounded from the pulpit. Sir James Mackintosh

was induced to hear the preacher, and one phrase he used in reference to

an orphaned family in his prayer, “thrown upon the fatherhood of God,”

was repeated by Mackintosh to George Canning, on whom it made such an

impression that he determined to hear for himself, and, having done so,

spoke of the sermon in the House of Commons as the most eloquent he had

ever listened to. Canning’s words gave a further impulse to the feeling

in favour of Irving, and noblemen, statesmen, poets, orators,

philosophers, artists, thronged to catch the streams of rhetoric thus

eulogised. Carriages with gorgeous coats of arms on their panels with

difficulty made their way to the church door, and titled ladies were

thankful for a seat on the pulpit steps. What lofty brows, what bright

eyes, what representatives of every sphere of human genius were grouped

before the preacher! He faltered not, but prophet-like in majesty of

aspect, with grand voice and in stately periods he expatiated on the

great themes with which he was charged. At last he attained the position

due to his powers, and was recognised as a king of men.

In 1827 the new church which had been built for Mr. Irving in

Regent-square was opened by Dr. Chalmers. Irving offered to assist him

by reading the chapter. He made choice of the longest in the Bible, and,

as if forgetful that a sermon was yet to come, expounded for an hour and

a half. The brilliant crowds that thronged the old and dingy building

did not follow him to the towered temple, which had been reared with

hopes of larger and more commanding influence. The novelty was over,

and, as Thomas Carlyle says, “Fashion went her idle way to gaze on

Egyptian crocodiles, Iroquois hunters, or whatever might be, and forgot

this man.” The church was well filled, but there was no longer the rush

of high aristocrats and men of genius; and Irving ceased to be the

orator setting London in a ferment with imperial accents, and was simply

a preacher limited to a large yet commonplace congregation. He might

still have been happy and useful, but the enormous popularity he had

enjoyed made the ordinary life of a minister distasteful to him;

consciously or unconsciously, he aimed at being the great light of his

age, and where genius failed, he resorted to singularity.

While still preaching in the Caledonian Chapel, he began to engage his

mind with the difficult questions of unfulfilled prophecy, and as it has

been said, “the gorgeous and cloudy vistas of the Apocalypse became a

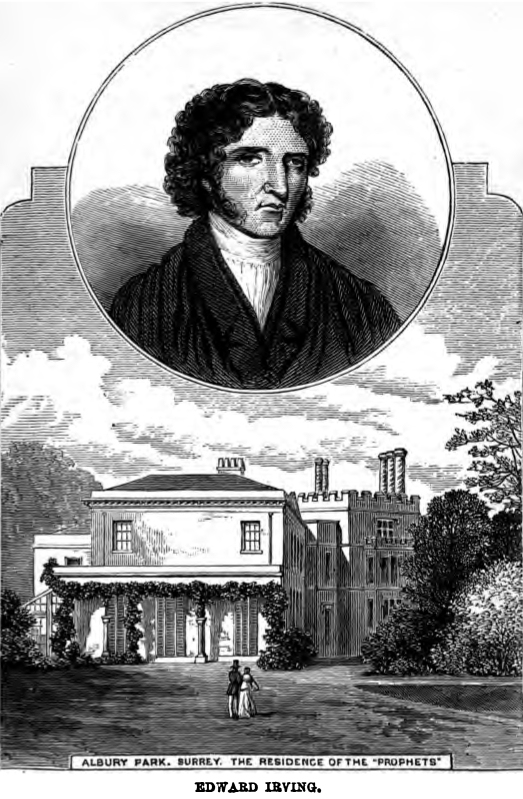

legible chart of the future to his fervent eyes.” Albury Park, the seat

of Mr. H. Drummond, was the scene of prolonged conferences, in which he

united with a number of ministers and laymen in the examination of those

portions of God’s Word which were supposed to bear on the destiny of the

Jews, or on the personal reign of Christ. But imagination rather than

reason was the faculty he brought to his prophetic studies, and many of

his interpretations of Scripture were forced and fanciful.

His first prophetical work was “Babylon and Infidelity Foredoomed by

God.” It contains, with much that is childish in argument, passages

rising to rapture of eloquence, and there is in it a description of

Popery so masterly and accurate that it must be quoted: “O, it is an

ample net for catching men! A delusion and bondage made for the world,

as the Gospel was a redemption made for the world! No partial error like

that of the Gnostics, framed out of mystic imaginations; or that of the

Arians, framed out of the proud arguments of reason, but a stupendous

deception and universal counterfeit of truth, which hath a chamber for

every natural faculty of the soul, and an occupation for every energy of

the natural spirit, permitting every extreme of abstemiousness and

indulgence, fast and revelry, melancholy abstraction and burning zeal,

subtle acuteness and popular discourse, world-renunciation and worldly

ambition; embracing the arts and the sciences and the stores of ancient

learning, adding antiquity and misrepresentation of all monuments of

better times, and covering carefully with a venerable veil that only

monument of better times which was able to expose the false ministry of

the infinite superstition, and overthrow to the ground the fabric of

this mighty temple, which Satan had constructed for his own glory, out

of those materials which were builded together for the glory of God and

Christ.”

Having adopted Millenarian views, he preached them with his usual

fervour, and went to Scotland to warn his countrymen of the coming of

Christ. In his own county of Dumfries there was great excitement. On the

Sabbath, ministers closed their churches and went with their flocks to

hear him. From the scenes of his youth and childhood he passed to

Edinburgh, where he lectured on the Apocalypse in St. Andrew’s Church,

and though he began at six o’clock in the morning, vast crowds

assembled, and numbers were unable to get in. Soon after his visit to

Edinburgh he preached in Perth from a text in one of those chapters in

St. Matthew’s Gospel which have reference to “the coming of the Son of

Man.” While he was unfolding his theme the church was darkened by a

cloud, from which came a vivid flash of lightning and a tremendous peal

of thunder. He paused, and then with deepened solemnity quoted the

words, “For as the lightning cometh out of the east, and shineth even

unto the west; so shall also the coming of the Son of Man be.”

Unfortunately he became erratic, not only in prophetical interpretation,

but also in doctrinal statement. With all his powers, he lacked the

qualities of the theologian, and while sincerely desirous of making

known the truth, fell into serious error as to the person of Christ,

teaching that He had the grace of sinlessness, not by nature, but by the

indwelling of the Holy Spirit; in other words, that Christ had

propensities to sin such as we have, but that they were restrained by

Divine influence. On account of this heresy, and the disturbances caused

by the voices and strange tongues which he encouraged in his church, he

was deposed from the ministry.

He did not long survive this exercise of discipline. Yielding himself to

the guidance of foolish and fantastic men, he went to Glasgow on a

prophetic mission. When he got to the city, he took off his hat in the

street, exclaiming, “Blessed be the name of the Shepherd of Israel, Who

has brought us to the end of our journey, in the fulness of the blessing

of the gospel of peace.” In Glasgow he was stricken down by fatal

sickness. He was heard one day murmuring to himself in Hebrew, “The Lord

is my Shepherd,” and there was something of the old exultant swell of

voice as he went on. “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the

shadow of death; I will fear no evil: for Thou art with me; Thy rod and

Thy staff they comfort me.” His last words were, “If I die, I die unto

the Lord;” and in the forty-second year of his age, he found the rest

for which he had vainly struggled on earth.

He was buried in one of the crypts of Glasgow Cathedral, and near his

grave is a window in which John the Baptist is represented, but with

Irving’s grand head and face, as preaching in the wilderness.

But his writings are his best monument, and however much we may dissent

from his prophetical fancies, from his error as to the person of our

Lord, from certain eccentricities of thought, and from occasional

remarks on Methodism not over-courteous but balanced by others in which

he warms into eulogy; we must allow him the praise of being a great

master of spoken and written language, and of having given delineations

of Christian morality scarcely surpassed in the whole range of religious

literature. His discourses, in their blending of literary and historic

interest, in their gleams of softened beauty and their upheavals of wild

grandeur, suggest comparison with a noble prospect to be enjoyed from

the bridge that spans the Tay at Dunkeld. Hear by, Bimham stands proudly

in its Shakesperian fame; the river clear as glass rushes swiftly over

its rock-paven bed; in the foreground of the picture, half veiled by

delicate foliage, are the mansion of the Duke of Athol, with its fair

lawn sloping to the water, and the shattered cathedral in which Gawin

Douglas, the translator of Virgil, sat throned in prelatical pomp; and

beyond are dark firs, steep bald cliffs, and the hazy blue*of distant

mountains: such beautiful variety, such panoramic magnificence are to be

found in the discourses of Irving, of whose character we cannot say

less, than that he was a good man, and, up to the measure of his

convictions, a faithful minister of Jesus Christ. |