|

JEDBURGH is a small town

in Roxburghshire, noted in the annals of Border warfare. It was

frequently attacked by the English, and the broken arches and scarred

towers of a fine Abbey still testify to the violence of their assaults.

The scenery of the neighbourhood combines somewhat of the ruggedness of

the Highlands with the delicate beauty of a Devonshire landscape. The

old red sandstone presents itself in numerous bare precipices ; the

background is formed of picturesque interminglings of dark woods,

apple-orchards, meadows and corn-fields. Nor is the charm of water

wanting. The Jed, which has given its name to the ancient burgh, flows

by hazel copse and cultured slope, and in the shadow of firs “ that

crown the heights with tufts of deeper green.” This stream has gained a

poetic celebrity, for on its banks Thomson first watched the procession

of the “Seasons and Leyden", who sleeps in distant Java, has sketched

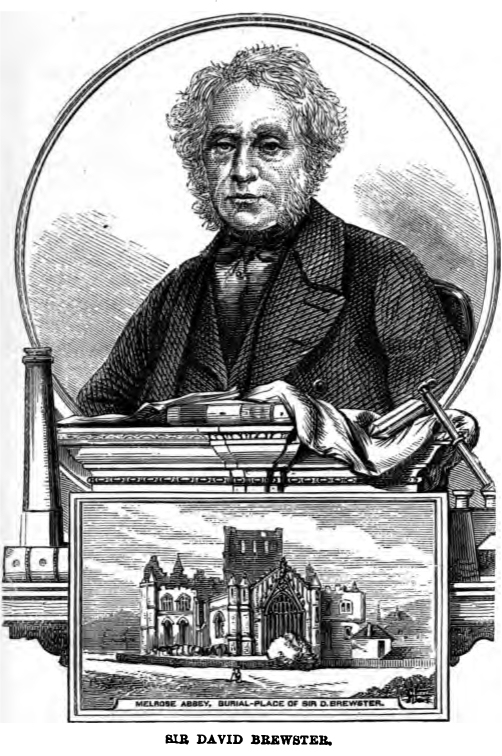

its beauties with a loving hand in his “Scenes of Infancy.” Sir D.

Brewsteb was born in Jedburgh, in the year 1781. His father was rector

of the Grammar School, a position to which he had been appointed, partly

through the influence of the minister of the parish, Dr. Macknight,

whose learning and acuteness found scope in the famous works on the

Gospels and the Epistles.

David was educated by his father. His mind was naturally quick and

retentive, and though never seen toiling over his school-books like the

other boys, he always had his lessons ready. Genius is often started on

its career by trifling circumstances, and David’s early bias towards

natural science was occasioned by seeing the prismatic colours thrown

out by some peculiarity in a window-pane in his father’s house. The

beautiful hues thus made visible, led him to eager inquiries as to the

refraction of light. He was aided in his investigations in reference to

that and cognate subjects, by acquaintance with several individuals who

had a local renown for scientific research or mechanical ingenuity. His

principal teacher was James Veitch, who resided about half a mile from

Jedburgh, in a valley gently sloping towards wooded banks and red scaurs.

His cottage, standing on a small patrimonial estate named Inchbonny, is

described as “pleasant to sight and sound, with its walls covered with

pear-trees, its sunny little garden, its hives of bees, its song-birds

and its murmuring brook.” He was a carpenter by trade, but was able to

construct telescopes, microscopes and other instruments with a precision

not surpassed by the workmen of Edinburgh or London. He delighted in

astronomical pursuits, and was the first to discover the great comet of

1811. Men of eminence in science and literature courted his society; and

Sir Walter Scott frequently said to him, “Well, James, when are you

coming amongst us in Edinburgh to take your place with our

philosophers?” The leafy dwelling, the workshop with its mechanical

curiosities, would have been an attraction to almost any boy, but were

specially so to one so eager for information as David Brewster. Though

he had afterwards teachers of greater name, it was from the philosopher

of Inchbonny he received the lessons which prepared him for his

scientific achievements. Nor did he forget his obligations, for when

honoured by a European reputation and by the diplomas and medals of many

illustrious institutions, he turned fondly to the sequestered valley in

which his early preceptor pursued the even tenour of his way.

When twelve years old, he was sent to the University of Edinburgh, where

he distinguished himself as a laborious and successful student, and took

his degree of M.A. while yet in his teens. Though he entered the

Divinity Hall, being intended for the clerical profession, he abated

nothing of his enthusiasm for natural science, and employed all his

available time in astronomical observations and experiments in

electricity and optics. After leaving the University he preached a few

times, but excessive nervousness and a number of discouraging

circumstances, induced him to abandon the plan of ministerial life which

had been formed for him. It is evident he could have had no deep

conviction of duty in reference to the work of the ministry. He had been

simply designed to it, as to a profession, without regard to conversion

or a Divine call. There may be instances in which in childhood

predilections and qualifications for the ministry are manifested, which

ought to be sacredly cherished by parents. But what kind of ministers

are boys likely to rise up who have never been affected by the love of

Christ, and have never thought of the grave responsibilities of the

ministerial calling, yet at twelve or thirteen are sent to College as

Divinity students, and then, with no more than the cold outlines of a

system of Theology in their minds, are ordained to the care of churches?

Who can wonder if Religion languishes, and Rationalism comes with axes

and hammers to break down the carved work of the old beliefs, when

pulpits are occupied and sacraments administered by men without

experience of the first elements of Christian life? Happily there has

not been in the past, nor is there now, the slightest tendency to this

mode of procedure in Methodism. Ho one can be received as a candidate

for our ministry, in reference to whom the following questions cannot be

answered in the affirmative: “Has he grace? Has he gifts? Has God given

him fruit of his labours?”

In 1810, Mr. Brewster was married to a daughter of the Macpherson who

gained both applause and obloquy by his real or pretended translations

of Ossianic poetry. For some time after his marriage the philosopher

resided in Edinburgh, and then removed to a small estate he had bought

in Roxburghshire, not far from Melrose Abbey. Allery was the name he

gave to his new abode, which commanded a fine stretch of country backed

by the Eildon Hills, and had the additional advantage of being

favourably situated for intercourse with Abbotsford and other seats of

distinguished literary men. This picturesque spot was held by him until

1838, when he was made Principal of the United College of St. Salvador

and St. Leonard, in St. Andrews; an appointment which necessitated his

removal to that city. He occupied the house in which the famous George

Buchanan once studied and wrote, and was in the midst of antiquities

replete with the interest of great names and startling events. He could

scarcely have gone to a place more suitable for a man of studious habits

than St. Andrews. The long, parallel streets are almost cloister-like in

their quietness; the wide beach, the sands of which glisten in the

sunlight as if strewn with particles of silver, with the blue sweep of

the noble bay, afford an ample scene for meditation or recreation; the

stern masonry of the old castle, the fragmentary glories of the

Cathedral, and the gaunt tower of St. Regulus, carry the mind back to

days when prelates vied with kings in power and pomp; and in the

cathedral yard are numerous historic tombs, one of which bears the

honoured name of Samuel Rutherford, and cannot be seen without a throb

of emotion by those who have yielded to the lovely charm of his

“Letters.”

Whether in Allery or St. Andrews, Mr. Brewster was ever busy with his

scientific labours, and by his success in them won distinctions from

almost every part of Europe, and the honour of knighthood from William

IV.; while geography took charge of his name, giving it to a cape in the

Arctic, and a river in the Antarctic region. He could almost have said

with Lord Bacon, "1 have taken all knowledge to be my province.” Few

subjects, relating either to the heavens or the earth, escaped his

attention; but it was in the domain of light and optics that he found

his most congenial tasks, and made discoveries which were hailed as new

glories for science. While engaged in his favourite studies, lie

invented an instrument which, though of no utility unless to pattern

designers, has given pleasure in tens of thousands of dwellings. This

was the kaleidoscope, the appearance of which caused immense excitement.

The tube, with its endless variation of form and colour, was sought by

all ranks and ages, from peers to peasants, from grave philosophers to

little children. Kaleidoscopes could not be made with sufficient

rapidity to meet the demand. Shops were besieged, and people left their

money in order to insure the coveted article. But the inventor gained no

pecuniary advantage; means were adopted to evade the patent he took out,

and though it was said he ought to have realised one hundred thousand

pounds, he was not profited to the extent of a single farthing. Sir

David Brewster also gave to the stereoscope its present form, for though

the principle of binocular vision had been long understood, and though

instruments had been made by which two pictures had been brought into

one view, and their objects set in apparent relief, he was the first to

bring out the instrument now in universal use. One of these he took to

Paris, where its adaptation to photography was at once appreciated.

Crowds flocked to see the wonders effected by the twofold lens, and the

instrument soon became extensively popular. His optical researches also

led him to make considerable improvements in the illumination of

lighthouses. Great difficulties were placed in the way of the adoption

of these improvements, and even his claim as the originator of the

dioptric apparatus was acrimoniously denied in favour of a Frenchman ;

but his services were recognised after, if not before, his death, and a

high authority has said: “Every lighthouse that burns round the shores

of the British Empire is a shining witness to the usefulness of

Brewster’s life.” Sir David Brewster was not only a scientific but also

a literary man. His first great work, projected while he was

comparatively young, was the “Edinburgh Encyclopaedia" for which he

wrote many articles. He was involved in immense troubles by want of

punctuality, and even utter neglect, on the part of numbers who had

promised articles, and pecuniarily the work was a failure but it remains

as a fine monument of the editor’s daring and his intellectual energy.

Thomas Chalmers was asked to be a contributor. At that time he was but

little interested in the themes proper to his ministerial office:

Mathematics had greater charms for him than Theology, and he made choice

of Trigonometry as his subject for the “Encyclopaedia.” But the death of

a beloved sister touched his heart, and he requested permission to write

the article “ Christianity.” This article has interest as being his

first purely religious composition for the press, and as indicating an

important crisis in his spiritual history. Though it has reference more

to the buttresses than to the inner glories of Christianity, the studies

necessary to its production brought him into closer contact with truths

on which he had hitherto looked with philosophic disdain.

An Essay on Whewell’s “Plurality of Worlds,” written by Sir David

Brewster for the “North British Review,” was expanded by him into the

volume so well known as, “More Worlds than One:” a work to which he

applied himself with the caution of the philosopher, the imagination of

the poet, and the faith of the Christian. While free from the

extravagant rhetoric, it has much of the splendour of Chalmers’

“Astronomical Discourses.” The glories of the heavens blaze over the

great argument; and the writer in a masterly manner shows the

unlikelihood of the magnificent worlds which appal our minds with their

sublime distances and stupendous magnitudes, being mere wastes without

sentient occupants. In his own vigorous way he suggests the thought,

that if we could rise to the orbs which gleam afar, if we could glide

from planet to planet and from sun to sun, we should witness most

wonderful manifestations of intellect and moral power, and mingle with

beings haying lips melodious with lofty psalms, and vision bright with

prophetic radiancy, and hearts ever intent on doing the bidding of their

Creator.

Sir David Brewster’s most elaborate work is the “Memoirs of the Life,

Writings and Discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton.” He spared no trouble in

the execution of the task he had set himself, visiting Woolsthorp, where

he saw the tree from which, it is said, the apple fell which turned

Newton’s thoughts to the law of gravitation, and Grantham, where he saw

the venerable school-house in which he was educated: he also obtained

access to papers in the archives of the Earl of Portsmouth, which

hitherto had only been cursorily examined, but were found by him to be

of great value, as clearing Newton’s character from imputations of

unworthy conduct in his differences with Flamsteed. He would willingly

have proved Newton perfectly orthodox in religious belief; but though he

was not able to do this, he was convinced that his deviations from

Trinitarian doctrine were not so wide as they are usually stated to have

been. Other works were also published by Sir David Brewster; “The

Martyrs of Science,” “Natural Magic,” a popular “Life of Newton;” while

of miscellaneous articles he contributed three hundred and fifteen to

various philosophical journals, and seventy-five to the “North British

Review.”

Sir David Brewster was a Christian philosopher. His sympathies had

always been with the Evangelical section of the Church of Scotland, and

at the Disruption he identified himself with the Free Church. He was too

long a stranger to the spiritual life of the Gospel, but he was not a

doubter. He never indulged in the haughty scepticism which interferes so

much with our admiration of some of the eminent philosophers of the

present day.

His aim was not to sacrifice religion to science, but to unite them in

harmonious labours for the well-being of man.

It was not until late in life that Sir David Brewster entered into

conscious relationship with Christ. When he did become sensible of the

one thing he lacked, he sought the Lord with his whole heart. One of his

daughters had a conversation with him on the plan of salvation, in which

she related her own experience of the love of God. He listened, took her

in his arms and kissed her, and said with child-like simplicity, “Go

now, and pray that I may know it too.” The light he craved at length

filled his soul, and he could say, “I see it all so clearly myself. It

cannot be presumption to be sure, because it is Christ’s work, not ours

; on the contrary, it is presumption to doubt His word and His work.” On

another occasion he said, while tears filled his eyes, “O, is it not sad

that all are not contented with the beautiful, simple plan of

salvation—Jesus only, Who has done all for us!”

In 1859, he was appointed to the Principalship of the Edinburgh

University. His official life in St. Andrews was ruffled by strife and

litigation, for which he was to a large extent to be blamed. He was

somewhat pugnacious in disposition, and his strong phrases and

imperative manner, even in the assertion of what was right, tended to

rouse and embitter opposition. But in Edinburgh—and doubtless the

mellowing influence of Divine grace may be taken as accounting for it—he

worked in harmony with the College authorities, and one who had feared a

repetition of the St. Andrews squabbles, said after his death, “ Would

that Sir David Brewster had lived for ever; we shall never see his like

again ! ” His last public appearance was in Dundee, at the Meeting of

the British Association. The “old man eloquent,” with the beautiful

white hair and the expressive countenance, gave his testimony in favour

of revealed religion. One who was present wrote, “To see a phllosopher

like him, of worldwide reputation, vindicating the inspiration of God’s

Word, and humbly receiving the truth in the love of it, was most

encouraging.”

But though the faculties of his mind were well-nigh as bright as in the

days when with boyish glee he bounded along the bank of the Jed or

climbed the towers of the ruined Abbey, his body was weakened by lapse

of years. At one of the meetings he fainted on the platform. On his

return home, he expressed himself as feeling every day “ an inch nearer

the end since Dundee.” The closing days of his long and laborious life

were spent in his own charming Allery. He employed himself in calmly

arranging his affairs; and as each little task was completed, a letter

dictated or papers put in order, or books restored to their right place

on the shelves he would say, “There; that’s done.” The last time he was

in his study, his little daughter, the issue of a second marriage, came

in, and read to him the twenty-seventh Psalm and the sixth chapter of

the Epistle to the Hebrews, and then sung to him the hymn he always

delighted to hear, “There is a happy land.” When he left the study he

said, “Now you may turn the key, for I shall never be in that room

again.” When he undressed he said, “Take away my clothes, this is the

last time I shall wear them;” and when he lay down, “I shall never again

rise from this bed.”

Sir James Simpson visited him when on his death-bed, and told him that.

he hoped he might yet rally. “Why, Sir James, should you hope that?” he

asked; and then added, “The machine has worked for above eighty years,

and it is now worn out. Life has been very bright to me, and now there

is brightness beyond.” A little before he died, he said, “Jesus will

take me safe through.” One of the members of his family said, “You will

see Charlie,” a son who had been drowned many years before. After a

pause he replied, “I shall see Jesus, Who created all things; Jesus Who

made the worlds; I shall see Him as Ho is.” His closing testimony was,

“I feel so safe, so satisfied!” And then the blue eyes became dim, the

features rigid, and the patriarch was “for ever with the Lord.” His body

was borne through alternations of storm and calm, snow and sunshine, to

a grave near one of the sculptured windows of Melrose Abbey. On his tomb

there is an inscription highly appropriate to one who had studied the

properties of light with such assiduity, “The Lord is my light.” The

daughter who has written his life with tender care and in beautiful

words, has honoured his memory with a graceful poem, from which the

following lines are taken :—

“Under the storm!

Under the storm!

Lift ye gently the aged form!

Bear him tenderly down the stair—

Carry him out to the wintry air!

Let him into the shelter go

Of the plumy pomp of the conquer’d foe.

“Under the calm!

Under the calm!

Bear him along with a victor’s palm!

Borrow a glow from the purpled dell,

And a gleam from the river he loved so well;

Let the bells ring out a birthday chime

For a soul new-born from the throes of time.

“Under the snow!

Under the snow!

Into the damps and the dews below!

Lay him down with his long-loved dead,

Weep if ye will o’er his silver head,

We have not an honour to reach him now,

We have not a love that can touch his brow.

“Under the sun!

Under the sun!

Joy! for the saved whose race is run!

Joy! for the gift of the doubtless trust

That shall parry many a doubter’s thrust.

Joy! for the saint with his fair white stole,

Of Christ’s finished work in the glorious goal.” |