|

The change that has come over the social relations of

village and rural life generally within the last sixty years is very

marked in many ways. In former times, the means of communication

with the larger centres of population (indeed, many of the present

large centres of population scarcely existed then as such) were

defective, irregular, and tedious, in addition to being expensive;

the spirit and exuberance of youth had, consequently, few outlets,

and such as were, were often of a kind the reverse of conducing to

either self-respect, refinement, or mental elevation. Not

infrequently the facilities afforded by the large number of licensed

premises that then existed—Neilston, we are informed, had

fifty-eight inns and alehouses—and the comparatively low price of

intoxicants, with no restriction as to the hours the places might be

kept open, gave a bias to this mode of enjoyment, with all its

consequent evils, helped on, it is to be feared, in many instances

by the example of the senior members of the community. Indeed, no

greater improvement has taken place than there is in this respect

among the leading classes of village communities.

Sixty or seventy years ago, and even down to times nearer our own,

there seemed to be no disgrace in men in the first positions being

overtaken in liquor ! But, happily, opinion has branded this

practice so that it is now left a long way behind in the march of

progress, and though the legislature, with its prohibitory and

restrictive influences, may have aided in bringing about this

altered condition of affairs, the vast change in the drinking

customs—particularly in the better classes—of the country during

that time is not the result of legislation, but of a more subtle

influence—an influence which there is now reason to believe is

percolating through every class of society at the present moment.

And we look with confidence to the time arriving when the man, who

at the present day is rather disposed to boast of his Saturday’s

potations, will realize the stigma that attaches to such conduct,

and will come to see that intemperance is a thing to be heartily

ashamed of.

Many customs or usages that have now practically ceased to exist,

then contributed towards developing the evils of intemperance, among

young tradesmen especially. Seventy, or even fifty years ago,

tradesmen, particularly those who served apprenticeships under

indenture, of the then usual term of seven years, in what were

considered the better class of trades or handicrafts, underwent a

painful training in this respect during the seven years of their

novitiate. For example, no sooner had a lad of from thirteen to

sixteen years of age commenced his apprenticeship than an

“entry-money,” or sum to put him on a “footing” (for such it was

often called) with his new shop-mates, was imposed upon him. This

sum varied in different trades from half a sovereign to a guinea or

more,—for in some instances seven guineas in addition were paid for

trade purposes; then a night was fixed upon, generally a Friday

night, when all in the workshop, men and boys, met in a

public-house, and spent the night in carousal. Towards the expense

of this revel the journeymen contributed their quota, and the other

apprentices added theirs. The time was usually passed in eating,

singing, and drinking, and the young lad, having now made his

“baptism of alcohol,” was acknowledged a fully fledged apprentice,

and entered upon his particular duties as such ; next morning the

workshop savoured of “stale debauch.” It was now his business to do

what was known as the “scudgy-work ” of the shop: attend the fire,

sweep and keep the place clean, run errands for the

journeymen—including “running the cutter” for drink, for the more

bibulous of them—when he was praised as being clever if he escaped

being caught by the manager or employer, and felt flattered at the

praise. These duties he continued to discharge, while at the same

time he was being initiated into the mysteries of his calling, and

he was only relieved from them on the appointment of a new

apprentice; his successor taking over the scudgy-work. But the

matter did not end there, for he had now to “pay up” for being freed

of the “beesom”; and when the time came round for drinking his

successor’s entry-money, his new fine was his contribution to the

meeting. Nor was this always the end. If a young man got married, he

was expected to “pay-off,” and in some instances a similar

obligation followed the arrival of his first-born. In fact, the

methods had recourse to for “raising” money for drinking purposes at

this period were so numerous and varied,That by the time the young

man had finished his apprenticeship, it was many chances against him

that he had also learned something more than being a tradesman :

that he had become so bound round with the merciless fetters of an

acquired habit as to render it difficult, if at all possible, to be

broken away from in later years.

But many of the older trades have now passed away, and those

customs, “more honoured in the breach than in the observance,” have

passed with them, or been greatly modified in the trades that have

succeeded them; and, so far, a happier era has begun. Concurrently

with these changes, improved conditions have arisen, workmen’s

wages, for all kinds of labour, have greatly increased; money has

become more plentiful, and where this is properly used, want is less

pressing than in the earlier period referred to ; the burdens have

been made lighter also by the State educating, and, where necessary,

otherwise providing for the children, so that they are no longer the

victims of neglect. The health of the workers is now protected,

injuries compensated, and dangerous occupations specially guarded

against; and when years and decrepitude have rendered them no longer

able to earn their maintenance, provision is made for them by the

Old Age Pensions Act of 1908 ; whilst the amenities of life have

been broadened out and enlarged in a way impossible to the earlier

generation of artizans. With greater railway facilities for leaving

rural districts, with statutory and regulated annual holidays, it

has now been made possible for all classes, and at small cost, to

devote their leisure to more healthful, elevating, and rational

enjoyment. That this is taken advantage of is well exemplified in

the large numbers of respectable tradesmen who, annually with their

families, spend their holidays by the seashore, and the crowds that

take advantage of the many special excursions to spend their Spring

and Autumn and other holidays at different places of interest, in

enjoyment and healthful exercise which, in the younger generation

rising up, may lead, let us hope, to better regulated lives and

greater regard for decency and social order.

Yet, in the dawn of this brighter and more elevating outlook for the

toilers, it is painful to learn the extent to which the evils

incident to betting on horse-racing has permeated certain of the

working community in recent years, when the systematic book-maker in

the city sends his vampires to raid country districts among the

employes of different works. At the earlier period here referred to,

this practice was either entirely unknown, or viewed only as a kind

of horror carried on among a certain class of people of questionable

character and reputation. Let us hope that, bv the spread of

education and wider and better knowledge, a taste may be generated

and acquired for more healthful enjoyment, and so stamp out these

pests of society, by playing into whose hands the breadwinner’s

wages are too often curtailed, and the dependent family too often

made to suffer in consequence.

Physique.

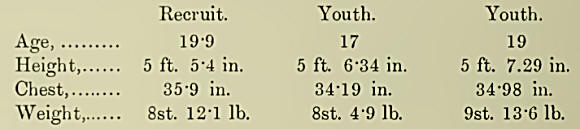

Closely associated with the foregoingsubject is the

question, Whether or not we as a people are deteriorating in point

of physique ? The recent statistics of the Anthropometric Committee

of the British Association, 1882-3, would seem to show some

foundation for thinking such was the case, at all events as applied

to the average recruit when compared with the average British youth

of the present day.

But, when we take a wider view of the matter, there

are substantial grounds for concluding that the race has improved,

taking like with like, for the above is scarcely a proper

comparison, seeing the source from which many recruits are drawn is

one where the essentials of subsistence are not always to be found

when tissue growth is keenest in demand, as is evidenced by the way

recruits grow and thrive every way when put on ample and regulated

rations. But if we compare class with class of the present

generation with those of a bygone age, the results show somewhat

differently; for example :—At the tournament held at Eglinton Castle

in 1839, the interesting and, in relation to our present inquiry,

instructive fact was brought out, that the armour obtained on loan

from the Tower, London, was mostly too small, and had to be “let

out” before it could be worn by men of like social position in our

own time. And as bearing on the same question, it may be noted that

at the International Exhibition in Glasgow, 1888, there was a

four-posted wooden bedstead among the exhibits at the Bishop’s

palace, lent by the Earl of Home, the present representative of the

family, which had belonged to and was used by the Black Douglas,

perhaps the most powerful and formidable knight of his age for

strength and prowess. On measurement, this bedstead was found to be

barely six feet in length, whereas a full-sized bedstead of the

present day is six and a half feet long. These two features, I

think, help us to conclude that we are an improved race, stouter and

taller than were the men of the earlier age. And as collaterally

showing that the whole European peoples have probably improved in

stature, it is reported in Laing’s Notes, as quoted by Bulwer

Lytton, in Harold, that in almost all the swords of the Norman age

to be found in the collection of weapons in the Antiquarian Museum

in Copenhagen, the handles indicate a size of hand very much smaller

than the hands of modern people of any class or rank. The

descendants of a people, who have for generations been workers in

mines and some kinds of factories or employment of a more or less

confining character, may become stunted in growth and deteriorate in

physique; but with an agricultural and rural population it is

different, and this applies to the original inhabitants of Neilston

parish, who have long been remarkable for size, strength, and

complexion, many of them being tall, stout, able-bodied men ; some

with fair, and others with dark complexions, but intelligent

features; and engaged largely in out-door pursuits. They are a

stalwart, big-boned race, as becomes the descendants of a people who

have been influenced in their stature by the primitive Britons of

Strathclyde.

The Manufactures of Levern Valley.

Within the last seventy years, the change that has

taken place in the trade of the Levern valley has been such as

might, without exaggeration, be designated a complete revolution. In

1831, when Charles Taylor published The Levern Delineated, the trade

of the valley consisted mainly of cotton spinning; and from

Crofthead factory, with 16,000 spindles, to Levern mill, erected in

1780, at Dovecothall, there were, he says, six cotton mills on a

large scale; in the New Statistical Account, 1837, Rev. Dr. Fleming

also speaks of the parish as abounding in cotton mills, printfields,

and bleachfields. But since their day, the trade of the valley has

undergone a very marked change. There are now only two bleachfields

that were in operation then, Kirktonfield and Arthurlie ; two cotton

mills, West Arthurlie and Levern mill; two printworks, South

Arthurlie and Gateside printfields—for Millfield printwork has been

unemployed since shortly after joining the calico combine, 1899.

Several of the bleachfields and one printfield that then existed

have been razed to the ground, viz., Waterside, Lintmill, High

Crofthead, Holehouse, and Nether Kirk toil bleachfields, and

Fereneze printfield; whilst Broadlie flax mill has been converted

into a bleaching and dyeing work ; Gateside cotton mill is now a

waterproofing manufactory, and \Y est Arthurlie bleachfield is now a

skinnery, the Spinning factory a bakery, and Cogan’s or Craig’s

Mill, long in a state of comparative ruin, is now a laundry. These

changes point to a revolutionary alteration in trade. Not that the

work of the valley is lessened thereby, or the output decreased, for

the contrary is the case; employment has been enormously extended,

and become more varied in character, much of it, especially in the

lower ward, being entirely new industry, whilst some of the works

where the industry remains the same have been more than quadrupled

in size.

Crofthead Thread Factory and Spool Turning Work is now the first or

highest work on the Levern—formerly there were four works higher up.

Of recent years this work has undergone great extension, and now

gives employment to fully 1,500 operatives, many of the girls coming

to it by train from Glasgow, Pollokshaws, and Barrhead, Bleaching,

dyeing, and mercerising is carried on at Broadlie Mill; and

Kirktonfield is specially noted for muslin, curtains, and lace

bleaching. In Gateside, printing is carried on in the

long-established Gateside printworks ; and waterproofing, a new

industry, has been established in what was formerly Gateside Cotton

Mill. In Barrhead, trade occupations are very varied, and

represented by—South Arthurlie Printing Works, an old-established

concern; Shanks & Company, Ltd., Sanitary Engineers, a new and large

industry giving employment to about 2,000 hands; Arthurlie Bleaching

Work; Cross Arthurlie Skinnery, a new industry; Sanitas and Darnley

Sanitary Engineering Works; Grahamston Foundry and Engineering

Works; Pulley Makers; Flock Spinners; Boilermakers; Brass Finishers;

Copper Works; Arthurlie Bread and Biscuit Factory; Co-operative

Bakery; Pottery Works; Wool and Hosiery Works; Cabinetmaking;

Joiners; Plumbers; and Blacksmiths.

These diversified industries bear evidence to the spirit of

enterprise and progress that has been everywhere spreading by leaps

and bounds in the district—especially in the lower district—until

what was only, even a quarter of a century ago, a comparatively

small community, has now become the populous and prosperous Burgh of

Barrhead.

It is interesting to note how very early the industry and push, that

seems always to have characterised the Levern valley, had

established a connection with the rising cotton industry of the

country by erecting what was the second mill in Scotland. In the

light of the present day it seems not a little remarkable that the

first cotton mill should have been erected at Rothesay on the island

of Bute. But the circumstance is explained by the fact, that in 1765

the laws of Britain required that all Colonial produce should be

landed in Britain before it could be imported into Ireland, and for

the accommodation of the Irish colonial trade, Rothesay was made a

Custom House station. Taking advantage of this, a cotton mill, the

first in Scotland, was erected in 1778 by an English firm. But it

soon afterwards became the property of the celebrated David Dale, of

Lanark mills fame, a man of great enterprise, and a native of the

neighbouring town of Stewarton, where his father was a grocer.

Levern mill, erected in 1780, followed closely after, being, as

already noticed, the second of its kind in Scotland.

The Old Parochial Board.

The provision made for the poor and destitute of the

parish under the old system, in which the landlords of landward

parishes assessed themselves and were relieved of one-half by their

tenants, the management of which was by the minister and elders of

the church, was often precarious in its nature, and always

unsatisfactory. But in the year 1845 the Poor Law (Scotland) Act,

came into force, and by it the circumstances of the poor of the

parish were placed upon an entirely different footing, and came

under the care of the Parochial Board, the duties of which were

carried out by an Inspector of Poor; the sick poor, in addition,

being attended to by the Parochial Medical Officer. In our parish,

which was non-burghal, the qualification for becoming a member of

the Board was being owner of lands and heritages of the yearly value

of £20. The funds for the relief of the poor were raised by

assessment, towards which owners and occupiers of houses both

contributed, and the whole administration of parochial affairs was

under the superintendence of a Central Board, the Board of

Supervision in Edinburgh. There were no special chambers for the

meetings of the Board. The meetings were held monthly, generally in

a room in the Inspector’s house set apart and paid for by the Board

as an office. Under this system the able-bodied poor had no claim,

but poor persons of seventy years, or even under that age, who were

so infirm as to be unable to gain a livelihood by their work, all

orphans, and destitute children under fourteen years, and all

suffering from mental disease were eligible, and all who were

certified by the Medical Officer as being unable to earn their

maintenance, were provided for. And, under certain conditions of

residence, foreigners, and people from other parishes, could acquire

a settlement and claim, entitling them to relief when destitute.

Where •doubt existed as to the alleged destitution being genuine,

the Board had the power of putting the matter to a test by offering

the party admission to the poorhouse as a residence. In Neilston,

forty years ago, there was a small poorhouse, under the care of a

matron, in which provision was made for the aged and infirm, and by

this arrangement the poor and sick of the parish were comfortable

and well provided for.

But with the introduction of the new form of Local Government, the

old Parochial Board has become obsolete, and superseded by the

Parish Council since 1895, under which the Poor Law administrators

are elected and representative. But though the venue has been

changed, the law in its power and purpose remains the same and

unchanged. The Chairman of the Parish Council under the new law is

ex-officio a member of the Commission of the Peace.

That there is, however, ample scope for improvement in the present

methods of Poor Law administration has been abundantly shown by the

voluminous reports of the recent Poor Law Commission. Both sections

of the Commission unhesitatingly condemn the present system, and

therefore, when Parliament comes to deal with the question, we may

naturally look for legislative reform of such a drastic character as

will bring the whole organisation of the Poor Law more into harmony

with present day opinions and recent cognate enactments; embodying,

probably, recommendations from both the majority and minority

reports of the Commission. |