|

In no particular has there been greater diversity of

opinion, and error, than in the accounts given of the origin

and distribution of the several water

courses of the parish by writers who have dealt with this question.

Some writers have ridiculed the errors of others, whilst they have

themselves fallen into equally grave mistakes when dealing with

other parts of the same subject.

THE RIVER LEVERN

The name is of Celtic origin, and signifies the

“noisy stream.” This is by much the largest and most important

stream in the parish, and throughout its past history it has always

been the same. The use of steam as a motive power has, no doubt, to

a great extent superseded its operations at many of the works on its

banks, but it is still a stream of first importance and great

beauty. It takes its origin in the Long Loch. This loch is situated

on the level uplands beyond Moyne Moor, and is about one and a half

to two miles long, and half a mile broad. From this origin it flows

through Harelaw Dam and farm, and in the lands of the latter is

joined by the Knock Burn, a tributary from the farm of Nether-Carswrell,

in a hollow on the upper lands of which there formerly existed Knock

Loch. With the exception of a small pond for the farmer’s mill, the

waters of this loch are now drained off. After crossing Kingston

Road, under a quaint old narrow bridge—which has recently undergone

repair, and been widened on one side—the Levern enters Commore Dam,

whence it passes through Waterside, where, for many years, there was

situated a bleaching work of that name. This was the first bleaching

work on the river, and as such, from the purity of the water, was

considered one of the most important in the valley for fine fabrics.

It is now, however, quite a ruin, having been driven out of the

trade chiefly on account of the extra cost of working, especially

from expense in coal, owing to its distance from any railway

station.

At this point the Levern formerly received the waters

of the “Lady Well,” a perennial spring now turned to domestic

purposes in supplying the town of Neilston with water, and mil be

elsewhere referred to. Having given off a branch here to turn a

wheel for the farm of Neilstonside, but which is now no longer used,

the river leaves the vicinity of the solitary ruin, and flows

through a series of most tortuous links—“The Links of Levern”—in the

meadow land, where it forms the inarch between the farms of

Neilstonside and Jaapston, and where, many years ago, there used to

be a considerable dam. It now crosses “the Keeper’s Road” under an

ancient arch, and passing the remains of the ‘‘Old Grain

Mill,”—Mali’s Mill,—to which it used to lend its power, it rushes

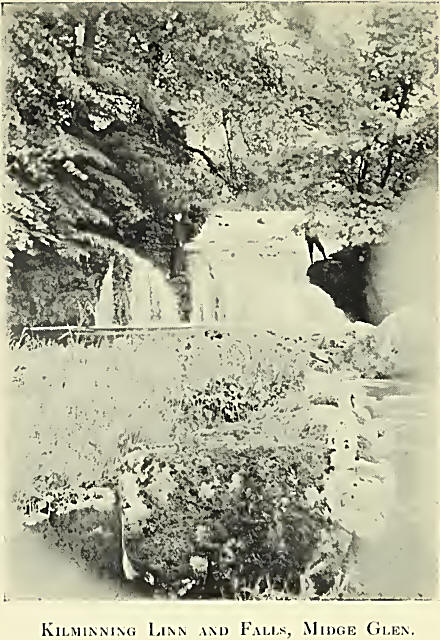

into Midge-hole Glen, or “Image-hole Glen,” for there is a local

tradition thus accounting for the origin of the name. During the

Reformation period, the iconoclastic zeal of some of the reformers

led them to drag the image of the Virgin from the religious house at

Waterside to the falls in this glen, w^here they dashed it on the

rocks in the bed of the stream, whence the name “Image-hole Glen,”

now corrupted to Midge-hole Glen. This glen is a very picturesque

ravine, in which there are two very fine water-falls, over which the

water plunges, especially when in spate, in white foam, into deep

basins beneath, which have been honoured by poetic notice, and have

received the names of “Kilnminning’s Linn,” and “Dusty’s Linn,” from

above downwards. Subjoined are the lines referred to :—

“Now rushing o’er Kilnminning’s Linn,

Now jouking ’neath brambles it goes;”

and

“Are hushed here as foaming the flow

Of Levern o’er Dusty’s Linn loud.”

The Image Glen then (for on the grounds of euphony

the word hole should be dropped from its name as an inelegant clog)

is beautifully wooded with overhanging trees on its eastern bank,

whilst on its western bank there is a right-of-way, which is a

favourite walk with the youthful lieges.

Having now reached the lower meadow land by these

falls, the waters glide smoothly along through Kilburn farm to what

was, until

lately, Lintinill Bleaching Works, formerly a “Wank

Mill.” For many years this was a prosperous and thriving concern,

but now it is a complete ruin. The river now crosses under Uplawmoor

Hoad to “High Croft-head,” also, until recently, a thriving

bleaching and dyeing work employing one or two hundred hands, men

and women, but of which not even the ruins are left, all having been

torn down to make concrete; the same fate having equally befallen

“Holehouse Laundry,” to which also the Levern gave a supply of

water. These works having been utterly destroyed, the workers, many

of them old in the service of the employers, were scattered in

helplessness.

“In fares the land to hastening ills a prey,

Where wealth accumulates and men decay.”

Hastening from these inhospitable scenes, the waters

pass through Crofthead Thread Works, and here the level of the

Levern valley is reached at a point coinciding with the east end of

Cowden Glen,, where it receives the water of Cowden Burn. This burn

is made up of the united waters of Shilford and Witch Burns. The

former rises in Tuphead Park and meadows, of Cowdenmoor farm ;

passing Shilford Sawmill they flow eastward to join the Witch Burn

in the meadows below. The Witch Burn flows from two sources, one in

Dumgrain Moor on the farm of Aboon-the-Brae, which runs in the

hollow south of Braeface hill, and thence through the meadows of

Braeface and Jaapston farms, and joins the other branch which rises

in the moorland south of Knockglass farm, and passes eastward by the

glen west of How-Craig’s-Hill, to its junction with the stream from

Dumgrain Moor.

The united streams now continue as the Witch Burn,

and cross under a bridge on Uplawmoor Road. Now flowing through a

tortuous channel where the banks consist of several high terraces

which the waters have scooped out in the course of long ages, the

burn plunges over a shelving rock forming an agreeable waterfall,

into the meadow land below, where it joins Shilford Burn as

previously stated. The waters of the united burns now continue to

flow eastward alongside the railway, till, on leaving Cowden Glen,

they join the river Levern as Cowden Burn at Crofthead Thread Works

as before indicated.

At Crofthead Mill the Levern gives off a lade or

millrace for the supply of Broadlie Bleaching and Dyeing Works,

thence passing under Levern or Crofthead Bridge it reaches the south

side of the turnpike road from Glasgow, and at Broadlie Mill passes

under this road from the south to reach the north side of the

railway, where it immediately receives the water from Killoch Glen.

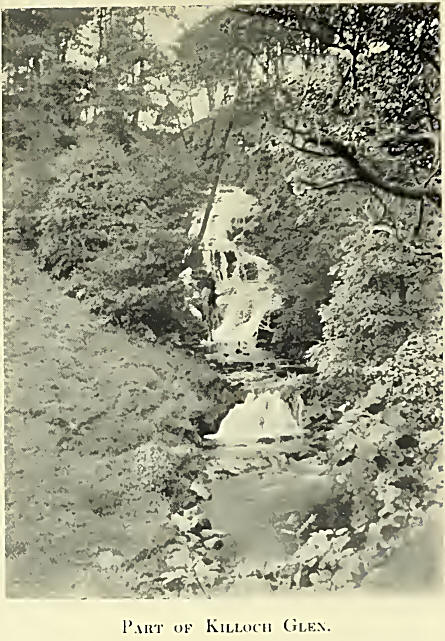

Killoch Burn rises by two heads. The first takes

origin in the moors of Caplaw farm and flows south, under

Sergeantlaw Road leading to Paisley. Continuing through Greenfield

Moor, it is joined by the second stream, the Witch Burn (the second

of that name in the parish), which springs in the meadows of

Foreside farm. The burn now passes under the road leading to

Capellie farm, and shortly gains the upper reaches of Killoch Glen.

In traversing this beautiful glen to arrive at the level of the

general valley at Killoch Laundry, where it joins the Levern, the

water is precipitated over a series of falls which present a grand

appearance when in flood.

The muses have been courted by more than one

poet 111 this beautiful glen, and the gentle Tannahill found

inspiration in singing the glories—

“O’er Glen-Killoch’s sunny brae.”

In the course of the descent two small streams are

taken from the Killoch Water, the upper as a mill-race to Killoch

farm, whence it is continued to the dam for Fereneze Printing Works

at Gateside, after which it joins the Levern ; the other, at a lower

level, is ponded up and led in pipes to Millfield Printing Works,

after which it also joins the Levern. Still pursuing its useful

career, the Levern runs eastward past the Waterproofing Works at

Gateside, West Arthurlie Cotton Mills, Chappell Laundry, Saunders

& Connor’s Sanitary Engineering Works, Lochrie & Nelson’s Plumber

Works, through Grahamston. Here it passes under the road leading

from Barrhead to Paisley and enters the Dunterlie valley, where it

is joined by the waters of Kirkton Burn, which have been pursuing an

equally useful but quite different course.

Kirkton Burn.-—The waters of this burn take origin in

the marsh and meadow-land surrounding the skirts of Neilston Pad,

both north and south. On the north, they are gathered into Craigha’

Dam, whence, after giving off a mill-pond for the Craig farm, they

flow into Kirkton Dam. In the south and east, they originate in the

meadows of Loanfoot, Lo Walton and High Walton farms, and flow into

Snypes Dam, whence they also pass into Kirkton Dam. From this dam

Kirkton Burn proper begins, and passes under the road leading from

Neilston to Mearns immediately on leaving the dam; thence it

continues past Kirkton Grain Mill, Kirktonfield Bleaching Works,

Netherkirkton Works, now in ruin, to Wraes

Grain Mill, whence it flows through Colinbar Glen to

Blackwood’s, or Arthurlie Bleaching Works; it crosses what was

lately Blackwood’s Dam, now filled up, giving off a stream to

Arthurlie Skinnery filters; thence by a conduit under the road

leading from Barrhead to Neilston it passes by the Skinnery, under

the road from Barrhead to Paisley, in a built channel, where it was

formerly ponded up (now drained off) behind Cross Arthurlie Inn; and

shortly after, as before stated, joins the Levern at Dunterlie

valley.

Walton Burn.—This burn takes origin in Snypes Moss

and the lands of Muirhead, Low Walton, and North Walton farms.

Having been first gathered into Walton Dam, it flows thence, and

crosses the road leading from Neilston to Mearns almost immediately.

At this point it constitutes the boundary between these two

parishes. Passing through Burnside farm, the water is again stored

up in Glanderston Dam, which burst with such disastrous consequence

in 1842, again referred to. Thi^ sheet of water now occupies what

was probably the gardens of Glanderston House, at one time the

residence of a branch of the ancient family of the Mures of

Caldwell, but of which not even the ruins now remain. Here, too, a

bleaching work was subsequently carried on by the family of

Cochrane, afterwards of Kirktonfield. Glanderston Burn continues

from this dam to Springfield and South Arthurlie Calico Printing

Works; and now, sadly changed in colour by dye stuffs, it continues

its course by Arthurlie to Aars Road, which it crosses under the

name of Aars Burn. Flowing sluggishly thence to Darnley, it joins

the Brock Burn, and the conjoined waters pass on to Househill, where

they unite with the Levern, and continuing their course through the

lands of Nether Pollok, enter the White Cart at Crookston.

Craigton Burn.—This burn rises in the moss-land of

South Walton and Middleton farms, in the parish of Mearns; flowing

thence through the small glen between these lands, it reaches

Craigton farms, where it is collected into a small mill-pond and

drives a water-wheel; continuing its flow through the Craigton

meadows, it there becomes united with the water of the Brock Burn.

Brock Burn.—This burn draws its source from the

extensive moor west of Dodhill, in the parish of Mearns, from the

west side of the same hill, and the meadow-land of Banner Bank farm,

on the Stewarton Road. Flowing thence through Langton farm, it

crosses the road leading by the Craigtons from Neilston to Mearns,

and entering the meadows, there it receives the water of Craigton

Burn, as before stated. The Brock now continues past Fingleton Grain

Mill and South Balgray House, where it enters Gorbals Gravitation

Reservoir. From the reservoir the riparian or compensation water

continues through Waulk-mill Glen to Darnley, where it is joined by

the Aars or Walton Burn, and thence flows, as before mentioned, to

Househill, where it enters the Levern, and subsequently the Cart.

All the streams hitherto enumerated and described

have been flowing in a direction that is more or less eastward

through the parish, but there are four streams that in their course

flow towards the west. These are Thortor Burn, Pollick Burn, Lugton

River, and Cross-burn.

Thortor Burn.—The name by which this stream is

locally known, and the farm of the same name through which it flows,

is evidently a corruption of the words “Athort-the-burn,” that is,

across the burn, and has reference to the position of the farm-house

which is at the other side of the stream from the main road, The

waters of this burn are gathered from the moorland of “Thortor-burn”

farm, and after flowing down a narrow gully towards the railway,

they continue along the north side of the line, through the meadows,

into the east end of Loch Libo.

The Lugton.—This river takes origin from the west end

of Loch Libo, and passes beyond the boundary of the parish just as

it enters the policies of Caldwell. Continuing its course westward,

it passes through the policies of Eglinton Castle, where it is

joined by the Garnock from Kilbirnie hills; here it unites with the

Irvine, and so reaches the estuary of the Clyde.

Pollick Burn.—This water draws its source from the

moorlands and meadows of the several Uplaws and Linnhead farms.

Crossing the road above Uplawmoor station, it passes through Pollick

Glen, a very picturesque ravine, to Neukfoot; thence under the Joint

Line and turnpike at Caldwell station, where it enters the waters of

the Lugton quite near its source. This water constitutes the

newly-adjusted boundary of the parish in the west.

Dunsmuir or Cross-burn draws it source from Moorhouse

and Braco meadows, where it is ponded up, and was used at a saw-mill

formerly at Cross-burn, but now gone. After flowing through The Hall

farm and Caldwell policies, where it forms a small curling pond, it

joins the Lugton.

Lochs and Dams.

In a parish where the water supply is so abundant as

it is in Neilston, as evidenced by the number and variety of streams

that contribute to swell our main river, the Levern, as has been

pointed out, and where the water supply is wanted all the year

round, one naturally expects that there would be such provision made

as would place the regulation of the supply under the control of

those who required it, and this is found to be the case. Storage is

provided by lochs and reservoirs in the upper reaches of the parish,

as the general supply comes from the elevated moorland in the south

and west. First and most important of these water storages is

the Long Loch. This loch, which is from a mile and a half to two

miles long by half a mile broad, is situated about four miles from

Neilston, between Moyne Moor and James’ Hill. The surrounding

country is a bleak, rough tract of moss and heatherland, at an

elevation varying from 808 feet to 900 feet, which extends from

Dumgrain in this parish to Lochgoin Moors in the parish of Eaglesham.

The boundary line between the parishes of Neilston and Mearns passes

longitudinally through this loch, and continues across Harelaw Dam,

into which the water from Long Loch flows. The character of the land

by which this sheet of water is surrounded, being free from all

manure contamination— none of it being under cultivation—renders it

an admirable gathering ground, and the water being naturally soft,

is in every way adapted for domestic purposes. From this source the

town of Neilston now obtains its water supply by gravitation,

supplementary to the excellent spring water from the Lady Well.

Harelaw Dam.—This is a large body of water, being the

surplus storage of the overflow water from Lono-Loch. There are one

or two small islands in it, and in early spring they swarm with the

nests and squabs of seagulls, which have come inland from the coast

for breeding purposes.

Commore and Crofthead Dams are places of storage for

the Levern in its upper reaches, after leaving which it continues

its course as already described.

Snypes, Craigha’, and Kirkton Dams are places of

storage for the water of Kirkton Burn; while Walton and Glanderston

Dams store the water of Walton Burn. Craigton Dam is a small storage

for the former’s use. These dams are well stocked with

fish—trout, perch, and braze. Fcreneze Dam, at Gateside, is a

storage pond for Fereneze Printing Works. The water is brought from

Killoch Burn by a lade, as described when speaking of that

stream. West Arthurlie Dam is a place of storage for the cotton mill

of that name. Arthurlie Bleaching Works obtain their water supply

from Kirkton Burn at Colinbar Glen.

Formerly there existed on the lands of Nether

Carswell a considerable sheet of water—the Knock Loch—which is

referred to and marked in many of the older maps and records of the

parish ; but the water of this loch was drained oft’ many years ago,

with the exception of a small millpond for the farmer’s use. The

water is continued into the meadows below, where it joins the Levern

as the Knock Burn. On the land of Greenhill Farm there at one time

existed a small collection of water— Greenhill Loch—marked on some

local maps, but it also has long since been drained away.

Loch Libo.—This beautiful and picturesque loch lies

near the western border of the parish, in the valley between

Caldwell Law on the north and Uplawmoor Wood on the south. The

turnpike road leading into Ayrshire passes along its southern edge

for about a mile. The district railway from Glasgow to Kilmarnock

runs along the margin of the water, yet in such a way as simply to

lend variety and animation to the scene. Viewed from the slopes of

Uplawmoor Wood, everything about the loch looks calm and peaceful.

In its sedgy surroundings, the gaunt heron (Ardea cinereci) may be

seen fishing in patience, and the round leaves and creamy yellow

trumpets of the water lilies (Nymph cea cdba) observed floating on

its surface—what time the month of July brings round Glasgow Fair.

The monotonous note of the coot (Fulica atra), the wild duck (Anas

boskcis), and water-hen (Gcdlinula chloropus) are to be heard as

they glide over its surface, leaving the wavelets of their rippling

course behind them in their wake. The stately spike of the reed

mace (Typha latifolia) and the delicate colour and soft waxy flowers

of the bog-bean (Menyanthes trifoliatci), that adorn its marshy

margin, all contribute to enhance a scene of transcending

loveliness. On a calm day its tranquil waters form a mirror in which

the umbrageous woods that skirt the surrounding hills, and the green

hills themselves, are gracefully reflected in its transparent

depths.

The loch, in its general outline, is of an oval form,

which renders it more pleasing to the eye. As already stated, the

water from “Thortorburn” glen flows into it from the direction of Shilford, through the meadows of Banklug Farm, to the east; whilst

from its western extremity the Lugton river takes origin. Loch Libo

is well stocked with fish, especially pike, but eels, perch, and

braze are also abundant.

For many years coal was profitably wrought 011 the

southern edge of the loch, but about 1791 the waters broke in upon

the underground workings, deluging the pit and drowning several of

the unfortunate workmen. Since then, although attempts have been

made to renew operations, nothing special has come of them, and the

pit is now closed.

Hartfield, Brownside, or Caplaw Dam—for this sheet of

water is known by each of these names—is produced by the waters of

the Altpatrick burn having been ponded up 011 Hartfield moor. The

Alt-patrick water flows eastward from this dam to Glenpatrick Carpet

Works, near which it is known as the Brandy Burn. This water

constitutes the boundary between the parishes of Neilston and

Paisley. The volume of water in the dam varies with the weather

conditions, but it is always kept well stocked with fine trout by

the parties owning the shooting on the surrounding; moor.

On the top of Fereneze hills, at an altitude of about

GOO feet, is Harelaw Dam, the waters of which are collected from the

moorland around Duchal-law. The boundary between Neilston and

Paisley parishes passes through this sheet of water.

Spring Wells of Neilston.

Previous to the adoption, in 1892, of the scheme for

“Neilston Special Water Supply” from the spring at Lady Well,

situated near the old bleachfield of Waterside, the water supply of

the inhabitants was drawn, for all domestic purposes, from a number

of spring wells, mostly with hand-pumps on them, that were

distributed throughout the different parts of the town and

neighbourhood. These wells have now all been closed by order of the

sanitary authority, as the subsoil through which the water

percolated had, by long years of defective drainage and constant

use, become more or less contaminated with sewage. In the older and,

at that time, more densely peopled part of the town, sewage, on

chemical analysis, was found to have made its way into the water of

most of the wells to such a degree as to render them, in time of

drought especially, a source of danger to the inhabitants,

who were obliged to use them, having no alternative means of

obtaining water. But though no longer in use, I consider it a matter

of local interest that they should be enumerated, their locality

pointed out, the names recorded by which they were known, and the

quality of the water they yielded referred to, especially as by this

means it will be possible to point out the strati-graphic limits

within which it was quite safe, in sinking a well, to expect to

obtain a supply of water.

The number of wells in the town and neighbourhood,

except in seasons of extreme drought, afforded an ample supply of

water to the inhabitants, but its quality was not always to be

relied upon, especially in periods of protracted dry weather. During

such times, when any disease of an epidemic character threatened the

district, the wells were duly examined and the water analysed, and

such sanitary and protective measures adopted as the requirements of

the outbreak seemed to demand, to give it check. These steps were

carefully carried out at the instance of the Sanitary Inspector and

Sanitary Medical Officers under the Parochial Board.

The wrells in and around the town were thirty-seven

in number, and I propose simply to enumerate them, giving the names

by which they were known, and making reference to the analysis of

the more important of them at the end :—

Lady Well, a spring of great importance, to be more

particularly referred to again; Murdoch-moor Well; Toll Well;

Betty’s Well; Big Well; The School Well; Wishart’s Well; Craig’s

Well; Wilson’s Well; Robertson’s Well; The Cross Well; Holehouse, or

the Doctor’s, Well; Bussell’s Well; High Broadlie Well; Marshall’s

Well; Waddell’s Well; Gray’s Well; Gallocher’s Well; Baker’s Well;

Telfer’s Well; Lang Laird’s Well; Wright’s Well; Writer’s Well;

Manse Well; Butter Well; The Rest Well; Kirkhill Well; Kirkhill

Cottage Well; Lindsay’s Well; Menteith’s Well; Nether Kirkton Well;

Killoch Well; Auchen-tiber Well; Barnfauld Well; Broadlie Well;

Broadlie Bleaching Green Well; and the well in Broadlie Wood.

These wells were not all equally available to the

public, as many of them were connected with private property, and I

will, therefore, give only the analysis, with extracts from the

remarks of Professor Penny, of Anderson’s College, Glasgow, of those

wells that were situated in the most populous parts of the town.

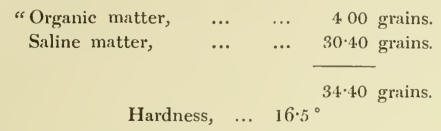

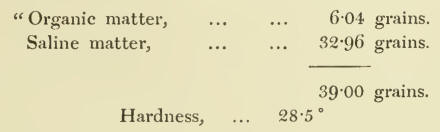

The Big Well.—“An imperial gallon of this water was

found to contain 34’40 grains of dissolved ingredients, consisting

of—

“The analysis shows that this water is strongly

charged with saline substances and contains a larger proportion of

organic matter than is usually found in good, wholesome waters.

“In colour, taste, and other physical qualities,

this water was found to be unexceptionable, but distinct evidence

was obtained of a small quantity of surface drainage and matter

analogous to sewage.”

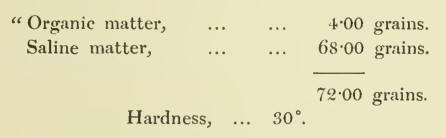

The Cross Well.—“It was found that an imperial

gallon of this water contained 72 grains of dissolved ingredients,

consisting of—

“The large proportion of sulphate of lime and

nitrates and chlorides in this water, is conclusive in showing that

it is polluted with the products of surface drainage, of the nature

of sewage from an inhabited locality. The organic matter is also in

notable quantity, and partly of an animal and noxious character.

“This is an impure and decidedly unwholesome water,

and unsuitable for any kind of domestic use.”

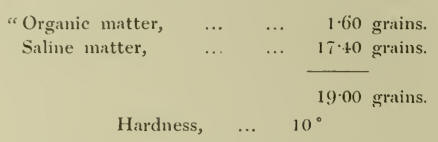

Gallocher’s, or the Chapel Well.—“An imperial gallon

of this water was found to contain 39 '00 grains of dissolved

ingredients, consisting of—

“This is an impure and polluted water, evidently

containing products from objectionable surface drainage. The

organic matter is in large proportion, and of noxious character. The

presence of nitrates and the marked quantity of sulphate of lime is peculiarly

indicative of its being polluted with matter from objectionable

sources.”

Yet, though decidedly unwholesome, this water was

clear to the eye and pleasant to the taste, and a favourite water

with the people in its neighbourhood.

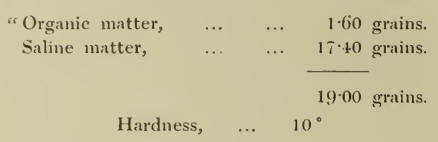

High Broadlie Well.—“An imperial gallon of this

water contained 19 grains of dissolved ingredients, consisting of—

“This water is of fair quality for domestic use. The

total amount of dissolved ingredients is not in excess of the

quantity contained in many waters used for town supply, and in the

proportion present none of the ingredients may be regarded as

hurtful or objectionable. But the presence of nitrates indicates

that surface drainage has access to the well.”

The water was held in high repute by the people who

used it.

The Toll Well.—“An imperial gallon of this water was

found to contain 11*5 grains of dissolved ingredients, consisting

of—-

“This is a good, wholesome water; in colour, taste,

and appearance, all that could be desired. The organic matter is

wholly of a vegetable nature, and in the proportion present quite

harmless. It is free from iron and nitrates, and from all injurious

metallic impregnation.”

The wells, in the order in which I have given their

analysis, extended mostly westward from the centre of the town, and

it is highly significant that the objectionable contamination

lessens in amount as we go west, until at the Toll Well—and the same

remark applies to the Doctor’s, or Holehouse, Well—which is quite

free of the town to westward, organic pollution is entirely

eliminated, and the water becomes quite a desirable water for all domestic and potable

purposes. And it is further worthy of observation, that this clearly

indicates the direction from which the body of water flows which

supplied the wells, viz., from west to east under the town.

The practical limits of the underground water, from

which nearly, if not absolutely, all the wells in the town had their

supply, is evidenced by the physical characters of the wells

themselves. To the west of the town they were near the surface and

shallow; towards the centre of the town many of them were quite

deep; and, again, as they got clear of the town, towards the east,

they became shallower, until at Kirkhill, they came almost to the

surface. It is thus apparent that the water gathered in the

extensive trappean hill district to the west of the town,

gravitating down their sloping surfaces and percolating through the

relatively porous formation on its way, found its natural bed in the

irregular trough that is thus shown to pass under the town, and

gained a more or less natural outlet at Kirkhill and Netherkirkton

in the east. This was amply verified during the introduction of the

drainage scheme through the town,—when it became necessary, from the

irregular levels of the streets, to make deep cuttings at certain

parts, as from the Cross to the bend in High Street, and from the

former to near the Chapel, where they were as much as 18 feet

deep,—the inflowing water so filled the pipe-track as to necessitate

the almost constant use of a powerful portable pump to admit of the

men getting on with the work at all. Whilst the trend of the

subterranean trough is from west to east, in which direction the

underground stream flows, its width would also appear to be well

defined by the sloping lands of Broadlie on the north and

north-west, and the meadow-lands of Kirkton on the south. Within

these limits, wells could be sunk almost anywhere with every

prospect of obtaining water. But on the hill-slope where the lands

of Broadlie dip towards the Levern, the water seems to be lost, as

boring in these parts was attended with failure.

By much the most important spring in the

neighbourhood is that of Lady Well, situated on the farm of Aboon

the Brae. During the existence of the bleaching works at Waterside,

the water of this spring was stored up, and was used for finishing

the finest kinds of bleached goods.

The very unsatisfactory, and, in the light of

analysis, even dangerous water-supply of Neilston, forced the

necessity of obtaining a purer water upon the notice of the

inhabitants, and, under the guidance of the then District Committee

of the County Council, accordingly, it was resolved to accomplish this by bringing into the town the

water from the powerful spring of Lady Well. The flow of water from

this well was favourably spoken of in the Gazetteer of Scotland as

to quantity, and the proverbial oldest inhabitant had no scruples in

declaring that it never varied summer nor winter. Accordingly,

measurements were taken and calculations made, and its adoption,

which was fixed upon, was looked forward to with confidence ; and,

as the water was of the very purest and seemed adequate, there was a

general feeling of satisfaction. The work connected with the

bringing in of this water-supply, and constructing storage tank,

into which it was led, west of the town, was completed in the autumn

of IS92, and for a time the supply seemed to be quite equal to the

demands made upon it. But now that the water of Lady Well came under

closer observation and measurement, the flow was found to vary very

materially in the winter and summer months; and that whilst the

supply was sufficient for the requirements of the inhabitants for

about two-thirds of the year, in the summer it proved altogether

inadequate, and the people had to be placed upon a limited

supply—the average maximum flow from the spring having varied from a

rate of about 54,000 gallons in 24 hours, to an average minimum

flow, during the same period, of about 12,500 gallons. This

fluctuation of supply, and the great inconvenience experienced by

the inhabitants in being placed on short allowance, led to some of

the wells—which had all been closed—being opened up again for use in

summers of great drought, with all the risks attendant, so that it

became necessary to look out for an additional water-supply.

At first it was thought that this might be

accomplished by sinking an Artesian well; and, accordingly, a bore

was put down on the outer skirts of the Pad, about a hundred yards

south of Kingston Road, but with very unsatisfactory results, the

maximum amount obtained being only about 1,700 gallons per day ;

although, considering where the bore was sunk—on the top of a trap

formation—it is difficult to see how other results could have been

expected. Finally, after an expenditure of £42G, both the engineer

and borer reported that, in their opinion, it would not be expedient

to proceed further with the boring operations. Blasts of gelignite

were discharged in the bore at different depths, in the hope of

reaching some under-flow, but without any more satisfactory results.

This was in the year 1899. The first 30 feet of this bore passed

through “blue boulder clay,” and the remaining 370 feet “through

very close-grained trap rock.”

The question of a sufficient water-supply being still

clamant, it was decided, after some negotiation, to apply to the

Local Government Board to acquire the right to 100,000 gallons of

water per day from the Long Loch, on the southern border of the

parish, and in due course the consent of the Board was obtained. The

estimated cost of the scheme was £1,900. This was in the year 1901,

but it was not till the beginning of 1903 that the work was

finished, and the water turned on. The Long Loch, as already

described under lochs, is situated on an extensive moor in the hilly

uplands to the west of the parish, and about four miles from the

town. It is a large body of water, about one and a half or two miles

long by half a mile wide, and admirably placed as a gathering-ground

for a domestic water, being free from all kinds of pollution, and

never likely to give trouble so far as regards shortage—a very

important matter for any community.

But scarcely had the inhabitants begun to realize the

blessings of this abundant water-supply, when they were startled by

an announcement of the supply having to be shortened—no water in the

town all night, supply cut off “from 7 o’clock p.m. till 7

o’clock a.m.” Not from want of water in this instance, for this was

in the summer of 1907, which had been one continuous deluge, but on

account of the service-pipes from the Long Loch being too small (six

inches in diameter), and “ air having got into them without

sufficient provision having been made for getting it out again.”

This error has now been put right by having larger pipes put in, at

a further cost, however, of about £900.

Referring to the variability of the flow from the

Lady Well spring, the fact that the flow never entirely ceases,

precludes it from being classified with “ intermittent springs.” Its

rising and sinking would appear rather to indicate variations of

level from time to time in the underground reservoir from which its

supplies are drawn, whilst the extensive moor of Dumgrane, which

occupies the great hollow in the trap formation around Knockanpe,

constitutes the gathering-ground. This moor spreads out for miles in

every direction, stretching beyond the parish of Neilston into that

of Dunlop, and is filled with treacherous moss and “wellies,” into

which cattle sometimes wholly disappear—a horse having sunk into one

of them a few years ago, possibly to form a subject of enquiry to

some geologist of the age when Macaulay’s Zulu will be studying St.

Paul’s from the vantage ground of the ruins of London Bridge—and

Lady Well would seem to form the principal, though not the onlv natural outlet. This to some extent is

evidenced by the fact that it is not until some time after

continuous and heavy rains, that the increased flow is experienced,

and that the low continues at nearly its maximum discharge long

after drought has begun to be felt by every other surrounding

object; as if the great extent of moss in the moor had first to

supply its own wants to perfect saturation, before allowing the

water to percolate through the surface to the underground reservoir

at all, whilst the latter continues to supply the spring long after

the surface moorland has begun to suffer from evaporation and

drought.

Climate of the Parish.

Where there is such diversity of altitude in the

land, as is to be found in the parish of Neilston, rising from a

level of about three hundred feet above the sea in the lower or

eastern district, to eight and nine hundred in the western or upper

district, it is naturally to be expected that there will be climatic

differences, for the inter-relationship that is always found to

subsist between climate and altitude is found to apply here also. In

the lower lands, as about Barrhead, where the soil is everywhere

fertile, the seasons are earlier by about two or three weeks than in

the upper district of Neilston and Uplawmoor, and harvesting is

correspondingly sooner begun ; there is greater dampness, and more

mists, and consequently the climatic surroundings are slightly

milder and more relaxing than in the upper district. Spring is

earlier, frost in winter is less severe, but fogs are more frequent

and prolonged. From the town of Neilston, which is about 500 feet

above sea level, the land westward rises gradually by gentle

undulations, and the natural drainage by the number of streams that

flow through it, causes it to be drier than that in the east. The

atmosphere is clearer, more bracing and invigorating, and although

the seasons are a little later, its comparative proximity to the

sea—being only about fourteen miles from the Firth of Clyde, at

Troon— makes it that they are never rigorous, whilst its great

salubriousness is evidenced, amongst other things, by the great

longevity of many of its inhabitants. In this relation it is

interesting to note that at a casual tea-party of five that came

under the writer’s notice, the respective ages of those present were

82, 81, 81, 77, and 75 years. As a matter of fact, few places can

vie with the western surroundings of Neilston, as, for example,

Uplawmoor and the Caldwell district, from a health point of view.

The climate is genial and mild; the exposure is west and south; and whilst the hill range of Oorkindale and Caldwell Laws

and Hartley Hill, shelter it from the north, the woods of Uplawmoor

screen it from the east; and the noble forest trees in the policies

round the ancient home of the Mures of Caldwell, the old tower on

the hill overlooking the delightful scene, and the unsurpassed, if

not unparalleled beauty of Loch Libo in the valley below, all

contribute to lend a charm and character to the surroundings, that

make the general restfulness equally with the health amenities of

the locality of the highest order, which, to be fully appreciated,

only require to be more widely known.

The prevailing winds in the parish for a large

section of the year— generally spoken of as about three-quarters of

it—are from the west and south, or some combination of these

cardinal directions; but in early spring, there is a good deal of

east wind, especially in the eastern parts of the parish, as from

Barrhead westward, where it is somewhat confined by the hill ranges

north and south of the main valley. The average rainfall,

notwithstanding the elevation, is comparatively low in the district.

Few things more clearly indicate the direction of the prevailing

winds in any locality than the growth of the older trees. They are

Nature’s owrn register, over which man can exercise very little

control. And it is instructive and important, and no less curious to

note in this respect, how the oldest trees on the Kingston and

Uplawmoor roads, for example, have their trunks leaning over towards

the east, and their largest and most luxurious branches swinging in

the same direction, demonstrating in the most obvious manner that,

during the long years of their comparatively slow growth, the

western or west by south winds have prevailed. The winds that blow

directly from the Firth of Clyde and the mountain peaks of Arran,

bring with them the invigorating influences of the shore, freed of

the excess of saline matter in the journey overland, but still

bearing with them the health-giving elements of ozone. In winter the

uplands are often covered with snow, which at times attains

considerable depth, through drifting, when accompanied with high

winds, but it seldom lies for any length of time, and the frost is

rarely of such intensity as to do harm to flocks or vegetation. |