|

The parish of Neilston is traversed by a great

valley, which, under different names, extends from the level land in

the north-east, where it is bounded by the parishes of Paisley and

Eastwood, to where it marches with the parishes of Dunlop and Beith

in the south-west. The eastern portion of this valley may be

considered as passing through Hurlet, Nitshill, and Darnley, and

here it is between two and three miles wide. From this it gradually

converges as it passes up the stream of the Levern until it reaches

to within about half a mile of Neilston station on the Joint Line of

railway; and at this point it narrows in so rapidly that, by the

time it reaches the station, the trap formations on either side have

met. From this point the outlet of the valley towards the west is

through a comparatively narrow break in the trap, known as Cowden

Glen, which extends south-westward for about a mile, and is about a

hundred feet wide. The boundary of this glen on the north side is a

continuation of the porphyrite traps of Gleniffer Hills, which here

rise as a bold escarpment to the height of about eighty feet; the

southern boundary is a more recent formation of volcanic ash and

tuff, and in it several eruptive dykes have been exposed through the

alteration on the turnpike road rendered necessary by the

construction of the Joint Line to Kilmarnock.

Emerging from this comparatively narrow ravine, the

valley begins gradually to widen out again, passing westward through

Shilford, Loch Libo, Caldwell, and Lugton sections. Beyond Caldwell

it again broadens out, until in the neighbourhood of Lugton, where

it enters into the parishes of Dunlop and Beith, it attains a width

of about three miles and merges into the carboniferous formations of

the Dairy basin. It will thus be seen that, as regards general

outline, the valleys of Levern and Lugton, viewed together, bear

some resemblance to a gigantic sand glass, two or three miles wide

at the eastern and western extremities respectively, but narrowing

to about a hundred feet in the middle, where the trap formations

meet in Cowden Glen. About the west end of* this short glen the trap

suddenly dips, by a fault, to about sixty feet, the depression or

blank thus caused being filled up with boulder clay, whilst the

hollows on the surface are filled up with stratified deposits of

sand, mud, and peat, evidently the remains of an old lake, being one

of a series of lakes, which it appears had at one time occupied the

valley from this point to Caldwell, the present Loch Libo being the

only one of the series now remaining.

Mr. James Binnie, of the Geological Survey of

Scotland, speaking of this formation, says:—“Up to 1867 the

picturesque little valley of Cowden beyond Crofthead on the road to

Ayrshire, was not known to possess any features of special

geological interest, but in that year, having been chosen as the

route of the district railway to Kilmarnock, it was invaded by the

navvy with pick and shovel to the utter destruction of all its

natural beauties. The gradients being steep, the excavations were

extensive, and at one point the bed of an ancient lake was cut

through, containing deposits of mud and peat lying between two

distinct layers of boulder clay. These stratified deposits were

found to contain numerous remains of vegetable and animal life, both

of higher and lower forms.”

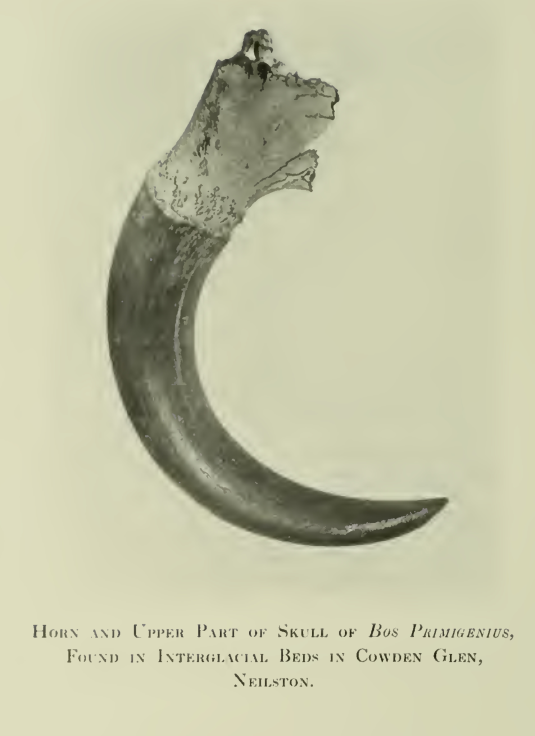

In the opening up of these stratified lacustrine

beds, the following fossil fauna were found near to the trap fault

already referred to,— the skull and horn-core of the Bos primigenius (this

interesting relic has now found a home in Caldwell House); part of

the horn of the extinct Irish elk, Mcgctceros hibernicus, and a few

bones of the horse, Equus caballus. The horn-core of the bos prijnus was

lying near the centre of the railway cutting, about six feet from

the surface, while the antlers and fragments of the Irish elk were

about thirty feet further into the hillside, and fifteen feet from

the surface. The fossil flora was represented by, besides mosses and

a sedge Scirpus lacustris, branches of Betulci cdbct, leaves of

the Salix alba, twigs of Calimun vulgaris, and Vaccinum myrtillus.

Through this great valley and closely alongside the

Joint Line Railway, the main turnpike road from Glasgow and Paisley

passes through the parish into Ayrshire, and divides at Lugton into

two principal roads, one leading to Kilmarnock and the other to

Irvine. At the north-eastern boundary of the parish, the Levern

valley as thus defined becomes sub-divided by a thick ridge of

sandstone, which runs from nearly opposite Darnley Hospital to

Barrhead, and along Craigheads, to the west of Barrhead ; and each

sub-valley has its own water course.

This rid ire makes a irreat break in the

carboniferous strata with which the main valley is filled, with the

consequence that the beds on the north side of the ridge are lower

in the series than those exposed on its south, which crop out

against the sandstone, giving a displacement, possibly of about

sixty fathoms, near Darnley. The trough of the southern sub-vallev

narrows towards its termination at Colinbar Glen, near Wraes Mill.

Various beds of sandstone, coalshale, clayshale, oilshale,

ironstone. and others, from a depth of over 175 fathoms, crop out on

either side of the valley against the trap formations, and in some

places lie at such an acute angle to them, as against the Fereneze

ash, as to show that these valley troughs have been formed by the

bursting upwards through their beds of the volcanic eruption, which

now in the form of the trap formation constitutes the northern and

southern hill ranges forming the boundaries already referred to in

the configuration of the parish. The carboniferous limestone of the

valley vields many fossils belonging to the following classes,

viz.:—Plantae, Zoophyta, Echinodermata, Annelida, Crustacea,

Brachiopoda, Lamelli-branchiata, Gasteropoda, Pteropoda, Cephalopoda, and Pisces. During

the recent formation of the Lanarkshire and Ayrshire Railway, which

passes through the parish from its eastern to its western border,

the excavations and cuttings exposed formations very varied in

character; trap and ash tuff, blue and boulder clay, the latter

containing boulders of various sizes—round and sub-angular—amongst

which the writer picked up a small, evidently carried, quartz, which

had a number of small pieces of gold imbedded in it.

f In a field known as the Wellpark, and situated

behind and to the east of Brig o’ Lea, a considerable section of

sand bed was passed through distinctly stratified in character, and

evidently the remains of some ponded up body of water. In the

rock-cutting at the south side of the entrance to Midge Glen, which

was wrought by the contractor as a quarry for ballast until the

railway was quite finished, it was observed that the whinstone was

distinctly columnar in its arrangement when exposed, and at the east

end of the same section, the friable volcanic ash was seen to

underlie the more solid stone, the latter having evidently flowed

out over it when in its liquid condition, as if the froth and ash of

the volcano had first boiled up and overflowed, and been then itself

covered over with the more consistent stream, which ultimately on

cooling formed the bulk of the erupted mass of which the hill is

composed. On Cowdenmoor farm, and about two hundred yards east of

the bridge across the railway, on the road leading from Uplawmoor to

Shilford, and on the south bank of the line, there is exposed a

large boulder well glaciated, the striae having a direction from

north-east to south-west; whilst at the east end of the village of

Uplawmoor, where the line passes through the skirt of the plantation

there, and for some distance westward, under ten feet of peat, a bed

of boulder clay was exposed, laden with boulders of different sizes,

mostly sub-angular, and many of them striated, resting on an outcrop

limestone consisting mostly of fossil shells, and stems of

encrinites at its eastern exposure. In passing through Pollick farm,

westward of Uplawmoor, the formation of the railway was entirely

through limestone, which is continued beyond the boundary of the

parish to the limestone quarries of Lugton and Beith.

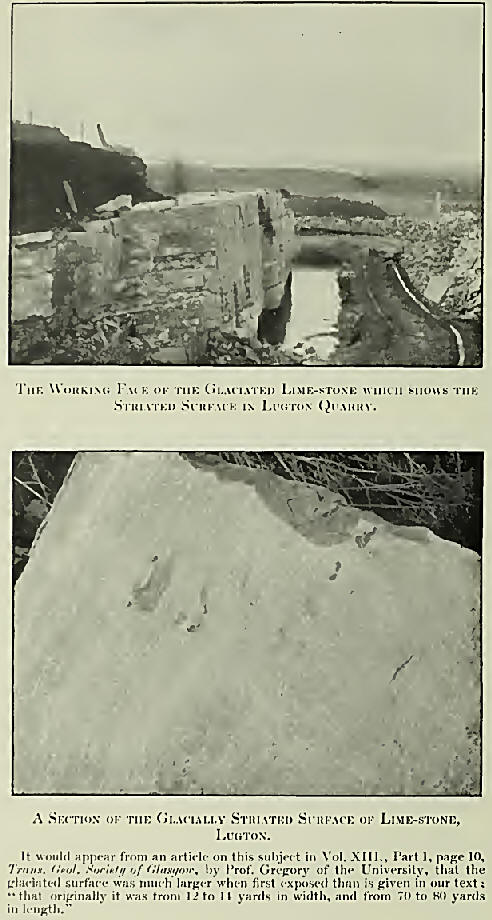

At this point I think it proper, as it is connected

with the limestone under consideration, although just beyond the

boundary of the parish, to refer to a very remarkable exposure of

glaciated surface in the lime quarry on Waterland farm at Lugton. In

190G the workmen, for blasting purposes, had to bare the limestone

of a top soil of about eight or nine feet in thickness, and on this

being cleared away there was exposed a broad platform of stone,

having a highly polished and gently undulating surface, with a

slight dip to the south-west. The dimensions of the surface thus

laid bare were about thirty feet by fifteen; but it was observed

that the same character of surface was continued under the still

unremoved soil of the field, to what extent was unknown. The

glaciation of this surface was quite remarkable for its high polish,

and when wet or washed clean, it shone with quite a glassy lustre.

But besides, and constituting a marvellous addition to its interest,

the whole exposure was marked with striations or groovings, some

deeper, some shallower, and many very fine scratchings, but all

clearly and definitely cut in long parallel lines, and all trending

from north-east to south-west, and the undulations on the surface

crossed these striations. At the western end of the exposure, the

natural surface of the stone dipped gently down towards the west,

and was unworn and rough, apparently indicating that the polished

surface represented some boss of rock that had been ground off; and

at places where this terminated somewhat abruptly, there was found

in the depressions, clay, containing bones, boulders, and other

deposits, huddled together. Shining everywhere through this

beautiful surface were the fossil remains of many marine structures,

shells, and crustaceans, cut through at all angles, and the outlines

of very large animals were clearly defined, while bones and teeth

were frequently met with, the whole surface presenting the

unmistakeable evidence of long bvgone and long continued glacial

action. In connection with glacier grooving, it may be further

pointed out, that when the alteration was made in the turnpike road

at the west end of Loch Libo, during the formation of the railway

there in 18G7, on baring the sandstone 011 the south side of the

road, there were several very pronounced gutters exposed in the

surface of the stone, running north-east and south-west. These

markings were about three inches wide, and fully an inch deep. At

the east end of the loch, and near the gravel quarry on the farm,

Head of Side,” there is an “osar,” or sand hill, quite as circular

in form as the track of a circus, “ the fairy ring,” a

relic no doubt of early glacier movement, or a once larger lake than

the present Loch Libo.

In its physical features, most of the land of the

parish may be said to lie along the hill ranges situated south and

north of the Levern valley. As has been already pointed out, this

valley passes through the parish from north-east to south-west, and

the general trend of the hill ranges is in the same direction.

To the north is the Fereneze range, which, by

Capellie, Lochliboside, and Caldwell, continues into Ayrshire. At

Caldwell it spreads out into a broad tableland, having Corkindale

and Caldwell Laws as its most conspicuous elevations, the former

rising to a height of 848 feet, and the latter to 800 feet above the

mean level of the sea. From these heights, spreading in a

north-westerly direction, the land becomes continuous with the

parishes of Lochwinnoch and Beith. To the south of the valley the

land begins to rise from Craigheads at Barrhead, and continues to

increase in elevation as it extends south and west, until it also

spreads out into a broad tableland through moss and rough pasturage

into that of the parishes of Mearns. Stewartou, and Dunlop. In the

direction of Kingston, where the water shedding is reached, the old

turnpike road rises by a succession of long step-like elevations,

which clearly indicate their trap formation.

The most prominent elevations in this westward

progress are the trap formations of Craig of Carnock, on the

borderland of Mearns parish ; Neilston Pad, also of igneous origin;

How-Craigshill, south of Uplawmoor Road; Dumgrain and Knockanae,

both north of Kingston Road;

Cannon Hock and Durduffhill, both south of Kingston

Hoad; Knock-maid, south of Uplawmoor, all rising on igneous

formations more or less interstratified. These hill ranges rise with

a varying but gentle acclivity from the level of the Levern valley

to Kingston, in the parish of Dunlop. In the east of the parish

beyond Barrhead, the valley gradually opens out, and becomes

continuous with the comparatively level land that passes on to the

Clyde; whilst westward through its Lugton section, it reaches the

Firth of Clyde by the broad alluvial lands that stretch onward to

Ardrossan and the Ayrshire coast.

The views that are to be obtained from several of the

most prominent hilltops in the parish are as varied as they are

grand and extensive. From Craig of Carnock, and from its more

gigantic neighbour, The Pad— so named from its fancied resemblance

to the cushion or pad ladies were wont to sit on when riding behind

gentlemen on horseback, a familiar enough practice in the days of

our grandfathers, when vehicles were less common than they are

now—the broad valley through which the Clyde passes, lies spread out

before the observer, from the east of the parish to the Campsie and

Kilpatrick ranges, including Campsie Fell and Glen, with the wide

spreading city of St. Mungo, and the numerous towns and villages

surrounding it stretched out between.

Nor does the broad prospect end here, for in early

spring when the distant sky is clear, and the hilltops of the

Grampians are covered with snow, the whole range from Ben Lomond to

Schiehallion, including Ben Arthur and its neighbours, Ben Cruachan,

Ben More, Ben Lawers, Ben Voirlech, Ben Nevis, and very many others,

come within the extensive prospect.

But the view from the top of Corkindale Law at

Lochliboside, for extent and grandeur, is unsurpassed by any hill of

equal height in Scotland, so wide and varied is the prospect it

affords. Its summit is quite green, and the ascent to it is so

gradual that, 011 reaching it, one can scarcely realize that such a

height has been attained, and if the day is favourable, the labour

entailed in attaining it is amply rewarded, so great is the range of

vision. To the north the Kilpatrick range, and the Vale of Leven,

Loch Lomond, with a number of its islands, and the great Ben Lomond

towering over it, and dominating the whole scene; Ben Ledi, the

“Cobbler,” and a host of other hilltops. Mount Tinto in the east,

with the towns and villages that intervene ; and in the south and

west the fertile lands of Ayrshire, and the coast line down to the

Rhinns of Galloway. Dahnellington and Cumnock hills, the heights of

Kirkcudbright, and the massive range of Saddleback, and Scafell in

England, in the Lake District of Cumberland and AVestmoreland, are

dimly visible, with the Trostan and northern hills of Ireland ;

while in the west and south-west, the grandeur of the prospect is

more immediate. Eglinton Castle in its surrounding woods, the shore

by Ayr bay, Troon, and Ardrossan, Arran, and Ailsa, in their watery

surroundings, while sailing vessels and gigantic ocean liners on the

waters of the firth give animation to the scene. With Kilbirnie

hills, Mistylaw, and the heights of Kilmacolm in the nearer view,

altogether they make up a prospect of unsurpassed interest and

grandeur. |