|

TELFORD, or TELFER,

a surname from Taillefer, Iron cutter, borne by a Norman knight, who

landed with the Conqueror, and we are told, went before the army to the

attack of the Saxons, singing chivalrous songs, throwing his sword in

the air and catching it again as it fell.

TELFORD, THOMAS, a distinguished civil engineer, was born of

parents in humble life in the pastoral valley of Eskdale, in

Dumfries-shire, in 1757. He received a limited education at the parish

school of Westerkirk, but afterwards taught himself Latin, French,

Italian, and German. At the age of fourteen he was bound apprentice to a

builder in his native parish, where he for some years worked as a

stone-mason. After the expiry of his time he went to Edinburgh, where he

studied the principles of architecture. In 1782 he proceeded to London,

and obtained employment under Sir William Chambers, in the building of

Somerset House. Here his great merit became conspicuous, and he was

subsequently engaged in superintending some works belonging to

government in Portsmouth dock-yard. In 1787 he was appointed surveyor of

public works in the county of Salop, a situation which he held till his

death. In 1790 he was employed by the British Fishery Society to inspect

the harbours at their respective stations, and he devised the plan for

the extensive establishment at Wick, in the county of Caithness, which

is now known by the name of Pulteneytown. IN the years 1803 and 1804 the

parliamentary commissioners for making roads and building bridges in the

Highlands of Scotland, appointed him their engineer; and, under his

directions, eleven hundred bridges were built, and 860 miles of new road

constructed. The Caledonian canal was also completed according to his

plans. In these and various other works which he executed in different

districts in England, Scotland, and Wales, his extraordinary skill

enabled him to surmount difficulties of the greatest magnitude. The most

stupendous undertaking in which he was engaged, and the most

imperishable monument of his fame, is the Menai Suspension Bridge over

the Bangour Ferry, one of the most magnificent structures of its kind in

the world. He also made several extensive surveys of the mail-coach

roads by direction of the Post-office, and in Sir Henry Parnell’s

‘Treatise on Roads’ will be found many details of his public works,

which are too numerous to be enumerated here.

In 1808 he was employed

by the Swedish government to survey the ground, and lay out an inland

navigation through the central part of the kingdom, with the view of

forming a direct communication by water between the North Sea and the

Baltic. In 1813 he again visited Sweden, and the gigantic undertaking

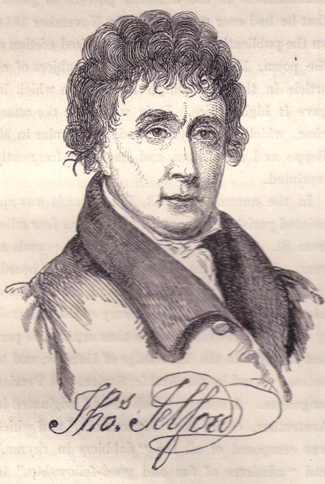

was afterwards fully accomplished according to his plans. His portrait

is subjoined.

[portrait of Thomas Telford]

His genius was not

confined to his profession. In early life he contributed several

poetical pieces of merit to ‘Ruddiman’s Weekly Magazine,’ under the

signature of ‘Eskdale Tam,’ and he addressed an epistle in rhyme to

Burns, a portion of which is given in Dr. Currie’s Life of the poet. But

though he soon relinquished the unprofitable trade of mere

rhyme-stringing, he remained a poet all his life. “The poetry of his

mind,” it has been finely remarked, “was too mighty and lofty to dwell

in words and metaphors; it displayed itself by laying the sublime and

the beautiful under contribution to the useful, for the service of man.

His Caledonial canal, his Highland roads, his London and Holyhead road,

are poems of the most exalted character, divided into numerous cantos,

of which the Menai Bridge is a most magnificent one. What grand ideas

can words raise in the mind to compare with a glance at that stupendous

production of human imagination?” He was a fellow of the Royal Societies

of London and Edinburgh, and, from its commencement in 1818, was

annually elected president of the Institution of Civil Engineers. His

gradual rise to the very summit of his profession is to be ascribed not

more to his genius, his consummate ability, and his persevering

industry, than to his plain, honest, straightforward dealing, and the

integrity and candour which marked his character throughout life. The

year before his death he wrote a ‘Report on the means of supplying the

Metropolis with Pure Water.’ He understood algebra well, but held

mathematical investigation in low estimation, and always restored to

experiment when practicable, to determine the relative value of any

plans on which it was his business to decide. He took out one patent in

his lifetime, and it gave him so much trouble that he resolved never to

have another, and he kept his resolution. He delighted in employing the

vast in nature to contribute to the accommodation of man. His eyes once

glistened with joy at the relation of the conception of a statue being

cut out of a mountain, holding a city in its hand; he exclaimed that

“the suggestor was a magnificent fellow.” Though ever desirous of

bringing the merit of others into notice, his own was so much kept out

of view that the Swedish order of knighthood of “Gustavus Vasa and of

merit” conferred on him, and the gold boxes, royal medallions and

diamond rings received by him from Russia and Sweden, were only known to

his private friends. The immediate cause of his death was the recurrence

of a nervous bilious attack to which he had been subject for some years.

He died unmarried, at his house in Abingdon Street, Westminster,

September 2, 1834, and was buried in Westminster Abbey. |