|

RAEBURN, SIR HENRY,

a distinguished portrait painter, the younger son of Mr. William Raeburn,

manufacturer at Stockbridge, a suburb of Edinburgh, was born there,

March 4, 1756. His ancestors lived on the border, and his father, on his

removal to Stockbridge, married Ann Elder, and commencing manufacturer,

became the proprietor of mills. He had two sons, William, who succeeded

him in his business, and Henry, the subject of this notice.

He lost both his parents

while yet young, and received his education in Heriotís Hospital,

Edinburgh, called by those who have been brought up in it, ĎHeriotís

Wark.í At the age of fifteen, he was apprenticed to a goldsmith in

Edinburgh. Soon after he began to amuse himself by drawing miniatures,

which, although he had never received any lessons, were finished in such

a superior manner as to excite attention. His master, astonished at his

performances, took him, about the year 1772, to see the paintings of

David Martin, then the principal portrait painter in the Scottish

metropolis. Martin, who painted many portraits in what Allan Cunningham

calls ďthe first starched Hudson style of Sir Joshua Reynolds,Ē at that

time resided in St. Jamesí Square. He received the young aspirant

courteously, and lent him several pictures, with permission to copy

them. He refused, however, to teach him how to prepare his colours,

leaving him to find that out for himself. In thus maintaining the

mystery of his profession, Martin acted properly enough. He had given

him all the assistance which a younger artist, not a pupil, is entitled

to expect from an elder, in the way of advice and encouragement, and so

far was entitled to praise rather than censure. But when his jealousy of

the rising talents of the youth, or his own captious temper, led him

somewhat hastily to accuse him of selling one of the copies which he had

permitted him to make, the case was different. Raeburn indignantly

established his innocence, and refused all further assistance from him.

He continued to paint

miniatures, for which there was soon a general demand, and he usually

finished two in a week. As this employment necessarily withdrew his time

from trade, an arrangement was entered into with his master, whereby the

latter, on receiving part of his earnings, dispensed with the young

painterís attendance. In the course of his apprenticeship he began to

paint in oil, and on a large scale, a style which he soon adopted in

preference to miniature painting.

When the expiration of

his apprenticeship rendered him free, he became professionally a

portrait painter. At the age of twenty-two, he married Ann, daughter of

Peter Edgar, Esq. of Bridgelands, with whom he received a handsome

fortune. He had fallen in love with this young lady while she sat to him

for her portrait. With the view of improving himself in his art, he

repaired to London, where he was introduced to Sir Joshua Reynolds. That

artist, struck with the genius displayed in his works, advised him to

enlarge his ideas by a visit to Italy, and even offered to supply him

with money for the purpose, which, however, Raeburn did not need. He

accordingly set out for Rome, accompanied by his wife, and well

furnished with letters of introduction from Sir Joshua to the most

eminent artists and men of science in that capital. He spent two years

in Italy, diligently engaged in studying the most celebrated works of

art. Returning to Edinburgh in 1787, he established himself in George

Street of that city, where he soon rose to the head of his profession in

Scotland, an eminence which he maintained to the end of his life.

In 1795 he built a large

house in York Place, the upper part of which was lighted from the roof,

and fitted up as a gallery for exhibition, while the lower was divided

into convenient painting rooms. His welling-house was at St. Bernardís,

near Stockbridge, on the banks of the Water of Leith. The history of his

life is limited to his professional pursuits. He painted the portraits

of many of the most eminent of his contemporaries in Scotland, and his

likenesses are universally regarded as most striking and exact, while

they are executed with a freedom, vigour, and dignity, in which he was

excelled by none. His style was free and bold; his drawing critically

correct; his colouring rich, deep, and harmonious; the accessories,

whether drapery, furniture, or landscape, were always appropriate; and

he had the peculiar power of rendering the head of his figure bold,

prominent, and imposing. His equestrian pieces, in particular, are

universally admired. The most interesting of his later works are a

series of half-length portraits of his literary and scientific friends,

which he painted solely for his own private gratification. A great

number of his portraits have been engraved. Constantly employed as a

portrait painter, he devoted no part of his attention either to

historical or landscape painting. He was elected a member of the Royal

Society of Edinburgh, of the Imperial Academy of Florence, and of the

New York and South Carolina Academies. On November 2, 1812, or, as

stated by some, in 1814, the Royal Academy of London elected him an

associate, and, on February 10, 1815, he was chosen an academician.

In 1822, when George IV.

visited Edinburgh, his majesty, as a compliment to the fine arts in

Scotland, conferred the honour of knighthood on Mr. Raeburn, a dignity

which was wholly unexpected on his part. A few weeks thereafter his

brother artists, as a mark of their respect, invited him to a public

dinner. Soon after, he was nominated portrait painter to his majesty for

Scotland, an appointment which, however, was not announced to him till

the very day when he was seized with the illness which terminated in his

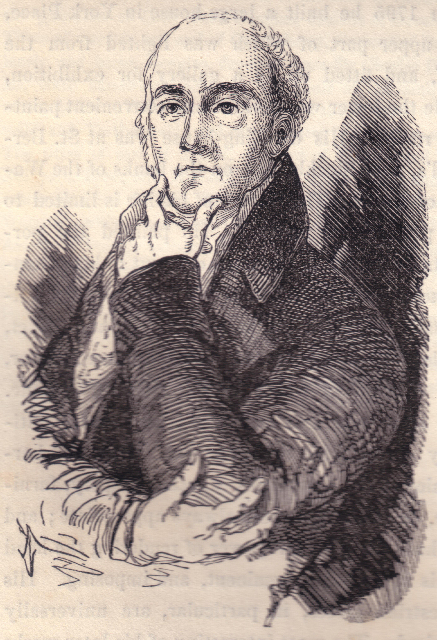

death. His portrait is subjoined:

[portrait of Sir Henry Raeburn]

The last pictures on

which he was engaged were two portraits of Sir Walter Scott, one for

himself, and the other for Lord Montague. He died, after a short

illness, arising from general decay, July 8, 1823. His widow survived

him ten years. He had two sons, Peter, who died at nineteen, and Henry,

who with his wife and family, lived under the same roof with his father,

and to whose children he left the bulk of his fortune, consisting of

houses and ground-rents on his property at St. Bernardís, Stockbridge,

which, in his latter years, he had occupied his leisure in planning out

into elegant villas and streets, and now forms part of one of the

suburbs of Edinburgh. |