|

PARK, MUNGO, an

enterprising traveler, the third son and seventh child of a respectable

farmer, was born at Fowlshiels, a farm on the estate of the duke of

Buccleuch, near Selkirk, September 10, 1771. He received the rudiments

of his education in his father’s family, and was afterwards sent to the

grammar school of Selkirk, where he distinguished himself by his

application and proficiency. He was originally intended for the church,

but, preferring the medical profession, he was, at the age of fifteen,

apprenticed to Mr. Thomas Anderson, a respectable surgeon in Selkirk,

with whom he resided three years. In 1789 he removed to the university

of Edinburgh, where for three successive sessions he attended the

customary medical classes. His favourite study at this time was the

science of botany, to prosecute his researches in which he made a tour

through the Highlands with his brother-in-law. Mr. James Dickson, who

had settled in London as a nurseryman and seedsman. On leaving college,

Park repaired to London, and was introduced by Mr. Dickson to Sir Joseph

Banks, by whose recommendation he obtained the appointment of

assistant-surgeon to the Worcester, East Indiaman. In February 1792 he

sailed for Bencoolen, in the island of Sumatra, where he collected a

variety of specimens in natural history. He returned the following year,

and, November 4, 1794, he communicated to the Linnaean Society a paper

containing a description of eight new species of fishes from the waters

of Sumatra, which was printed in the third volume of their Transactions.

Soon after, at the suggestion of Sir Joseph Banks, he offered his

services to the African Association, and engaged to go out on an

expedition to the interior of Africa, for the purpose of exploring the

source of the Niger. He sailed from Portsmouth, May 22, 1795, on board

the Endeavour, an African trader, and reached Pisania, a British

factory, about 200 miles up the Gambia, July 5. Here he remained five

months, learning the Mandingo language, and collecting information as to

the habits and customs of the countries in his route. He left Pisania in

the 2d of the ensuing December, and reached Yarra, a frontier town of

Ludamar, then governed by the chief of a predatory horde of nomade

Moors, February 18, 1796. Ali, the Moorish chief, detained him a captive

till July 1, when he made his escape. At this time he had been deprived

by the Moors of every thing but a horse, with its accoutrements, a few

articles of clothing, and a pocket-compass, which he had saved by

concealing it in the sand. Undismayed by the hardships and dangers which

surrounded him, he traveled on to the Joliba, or Niger, which he reached

at Sego, after a journey of fifteen days. He explored the stream

downwards to Silla, and upwards to Bammakoe, then crossed a mountainous

country to Kamalia, a Mandingo town, which he reached September 16.

Here, five hundred miles from the nearest European settlement, his

health at length gave way, and for upwards of a month his strength and

energies were entirely prostrated by a fever. After his recovery he was

detained in the same place five months more before he obtained the means

of journeying to the coast. At last, on June 10, 1797, he returned to

Pisania, and was received by the British residents there “as one

restored from the dead.”

After an absence from

England of two years and seven months, Mr. Park arrived at Falmouth,

December 22, 1797, and reached London on the morning of the 25th. An

Abstract of his Expedition, drawn up by Mr. Bryan Edwards, secretary to

the African Association, from materials furnished by Mr. Park, was

immediately printed for the use of the members. In June 1798 Mr. Park

went to reside at his mother’s house at Fowlshiels, where he spent the

summer and autumn in preparing his volume of Travels. His simple but

interesting narrative was published in 1799, with an Appendix,

containing Geographical Illustrations of Africa, by Major Rennell; and,

on its appearance, it was received with uncommon avidity, and has ever

since continued a standard work.

Having resolved to settle

in Scotland, Mr. Park married, August 2, 1799, a daughter of Mr.

Anderson of Selkirk, with whom he had served his apprenticeship. In

October 1801 he commenced practicing at Peebles as a surgeon. In the

autumn of 1803 a proposal was made to him by Government, to undertake a

second expedition to Africa; and, in December of that year, he quitted

Scotland for London. Owing to changes in the ministry, however, and

other unavoidable causes, the expedition was delayed till January 30,

1805, when, every thing being arranged, he once more left the shores of

England for the deadly and inhospitable regions of Central Africa. He

was empowered to enlist at Goree any number of the garrison under

forty-five, and to draw for any sum not exceeding £5,000. From Goree he

was directed to proceed up the river Gambia, and thence, crossing over

to the Senegal, to travel by such routes as he should find most eligible

to the banks of the Niger. In his first journey he had traced its

easterly course, but he had not been able to follow it down to its

mouth. His object now was to cross the country from the western coast,

enter Bambara, construct two boars, and, embarking on the river,

endeavour to reach the ocean.

On March 28 Mr. Park

arrived at Goree, from whence he proceeded to Kayee, a small town on the

Gambia, a little below Pisania, where he engaged a Mandingo priest named

Isaaco, who was also a traveling merchant, to be his guide. Here he

remained for some days arranging matters for the expedition, and here

commences Mr. Park’s interesting Journal of his last mission, which

includes regular memoranda of his progress and adventures to November 16

of the same year. On the morning of April 27 the expedition set out from

Kayee. It consisted of Mr. Park himself, with the brevet commission of a

captain in Africa, his brother-in-law, Mr. Alexander Anderson, surgeon,

with a similar commission of lieutenant, and Mr. George Scott,

draughtsman, five artificers from the Royal dock-yards, Isaaco the

guide, and Lieutenant Martyn and thirty-five men of the Royal African

corps, as their military escort. In two days they arrived at Pisania,

which they quitted on May 4, and on the 11th reached Medina, the capital

of the kingdom of Woolli. On the 15th they arrived at Kussai, on the

banks of the Gambia, and about this time one of the soldiers died of

epilepsy.

Park’s hopes of

completing the objects of his mission in safety depended entirely on his

reaching the Niger before the commencement of the rainy season, the

effects of which are always fatal to Europeans. The half of his journey,

however, had not been finished when the wet season set in, and, in a few

days, twelve of the men were seriously ill, and others were soon

affected in a greater or less degree by the climate. On the morning of

June 13, when they departed from Dindikoo, the sick occupied all the

horses and spare asses, and by the 15th some were delirious. On the 18th

they arrived at Toniba, from whence they ascended the mountains south of

that place; and, having attained the summit of the ridge which separates

the Niger from the remote branches of the Senegal, Mr. Park had the

satisfaction of once more seeing the Niger rolling its immense stream

along the plains. But this pleasure was attended with the mortifying

reflection, that, of the party that had set out with him from the coast,

there survived only six soldiers and one carpenter, with Lieutenant

Martyn, Mr. Anderson and the guide. Mr. Scott, the draughtsman, who had

been left behind at Koomikoomi, on account of sickness, died without

reaching the Niger. On August 21 Mr. Park and the few survivors embarked

in a canoe, and on the 23d they arrived at Maraboo. Isaaco was

immediately dispatched to Sego, the capital of Bambarra, to negotiate

with Mansong, the sovereign, for permission and materials to build a

boat for the purpose of proceeding down the Niger. Whilst waiting for

his return Mr. Park was seized with a severe attack of dysentery, but,

by the aid of medicine and a good constitution, he soon recovered. After

many delays, Mansong sent a messenger to conduct the traveler towards

Sego. The king and his chiefs were much gratified by the presents which

they received from Mr. Park, who, on September 26, proceeded to

Sansanding. It was with difficulty, however, that he procured from

Mansong, in return for his presents, two old canoes, wherewith he

constructed, with his own hands, and some assistance from one of the

surviving soldiers, a flat-bottomed boat, to which he gave the title of

his majesty’s schooner, the Joliba. In the meantime he was informed of

the death of Mr. Scott, and he now had to lament the loss of his friend

Mr. Anderson, who died, after a lingering illness, October 26. On

November 16 every thing was ready for the voyage, and, during the

succeeding days, previous to his embarkation, which was on the 19th, Mr.

Park wrote several letters to his friends in Great Britain, with which

Isaaco the guide was sent back to the British settlements on the Gambia.

Some time elapsed without

any farther intelligence being received of Mr. Park and his companions;

but in the course of 1806 various unfavourable reports became current

regarding their fate. Information was brought down to the coast by the

native traders from the interior of Africa, to the effect that Mr. Park

and those with him had been killed during their progress down the river.

Lieutenant-general Maxwell, the governor of Senegal, in consequence,

engaged Isaaco, Mr. Park’s former guide, to proceed to the Niger, to

ascertain the truth of these rumours, and in January 1810 he left

Senegal on this mission. He returned on September 1, 1811, bringing a

full confirmation of the reports of Mr. Park’s death; and delivered to

the governor a Journal from Amadi Fatouma, the guide who had accompanied

Park from Sansanding down the Niger, which, after being translated from

Arabic into English, was transmitted by him to the secretary of state

for the colonial department. From the information procured by Isaaco, it

appeared that the expedition proceeded from Sansanding to Silla, whence

Mr. Park, Lieutenant Martyn, three other white men, three slaves, and

Amadi, as guide and interpreter, nine in number, sailed down the Niger;

and in the course of their voyage were repeatedly attacked by the

natives, whom they as often repulsed with much slaughter. At length

having passed Kaffo and Gourmon, and supplied themselves with

provisions, they entered the country of Haoussa. Park had delivered some

presents to the chief of the Yaouri, a village in this district, to be

transmitted to the king, who lived at a little distance. The chief,

having learned that Park was not to return, treacherously appropriated

them to himself, and sent a message to the king that the white man had

departed without giving them any presents. At Yaouri, Amadi’s engagement

with Park terminated, and on going to pay his respects to the king he

was put in prison, and an armed force was sent to a village called

Boussa, near the river side, to intercept Park’s progress. This force

was posted on the top of a rock, which stretches across the whole

breadth of the river, and in which there is a large cleft or opening

through which the water flowed in a strong current. When Mr. Park

arrived at this opening, and attempted to pass, he was attacked by the

natives with lances, pikes, arrows, and stones. For some time he

resolutely defended himself; but at length, overpowered by numbers and

fatigue, and unable to keep the canoe against the current, he laid hold

of one of the white men and jumped into the water. Lieutenant Martyn did

the same, and they were drowned in the stream in attempting to escape.

One slave was left, and they took him and the canoe, and carried them to

the king. After having been kept in prison for three months, Amadi was

released; and obtained information from the surviving slave, concerning

the manner in which Mr. Park and his companions had died. Nothing was

left in the canoe but a sword belt, of which the king had made a girth

for his horse, and this belt Isaaco afterwards recovered. Captain

Clapperton in his second Expedition received accounts confirming this

statement, and visited the spot where the travelers perished. He was

likewise told that the chief of Yaouri had some of Park’s papers, which

he was willing to give up to him, if he would go to see him. The Landers

also visited the place, and were shown by the chief one of Park’s books,

which had fallen into his hands.

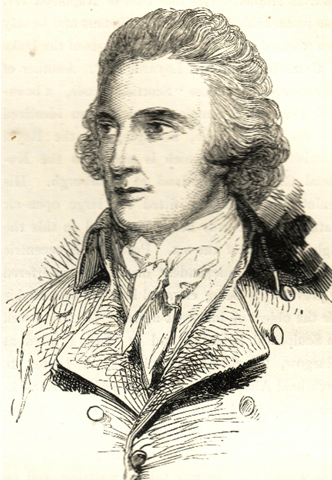

The portrait of Mungo

Park is subjoined:

[portrait of Mungo Park]

Mr. park’s death is

supposed to have taken place about four months after his departure from

Sansanding. Of his enterprising spirit, indefatigable vigilance, calm

fortitude, and unshaken perseverance, he has left permanent memorials in

the Narrative of his Travels, and in his Journal and Correspondence,

published in 1815, with his Life prefixed by Mr. Wishaw. His widow, who

was left with three children, died in February 1840.

PARK, PATRIC, a sculptor of considerable genius, the son of

Matthew Park, an eminent builder in Glasgow, who erected the new part of

Hamilton palace, was born in Glasgow in 1808. He early evinced a decided

taste for art, and studied at Rome for some years, as a pupil of

Thorwaldsen. In 1834 he settled in London, and was much engaged in bust

sculpture. At different periods he had a studio in Glasgow and

Edinburgh, and latterly at Manchester. In 1851 he was elected an

associate of the Royal Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture, and

Architecture, and was afterwards chosen an academician. He excelled

principally in busts, and those of many eminent personages of his time

were executed by him, among whom may be mentioned Thomas Campbell the

poet, and General Sir Charles Napier. His fine bust of Napoleon III. was

remarkable for its faithful likeness and beauty as a work of art. So

also are his busts of the Duke of Cambridge and Mr. Layard, M.P. Another

of his master-pieces is the “Scottish Lassie,” a beautiful head of a

female in marble, an idealized likeness of his wife, belonging to the

Royal Scottish Academy, which is placed in the National Gallery of

Scotland at Edinburgh. His genius was peculiarly fitted for large

open-air statues, but he was never employed in this the highest branch

of the art. Perhaps his eccentric character and independent disposition

interfered to prevent his being engaged in what was all his life the

object of his great desire. He wrote well on Sculptural subjects, and in

1846, printed at Glasgow, for private circulation, A Letter to Archibald

Alison, Esq., LL.D., sheriff of Lanarkshire, ‘On the Use of Drapery in

Portrait Sculpture.’ He died at Warrington, Aug. 16, 1855. He had gone

from Manchester to give a gentleman whose bust he was taking a sitting,

and on his return to the station at Warrington, he perceived a porter

endeavouring to carry a heavy trunk. Rushing forward to his assistance,

in the attempt to lift it, the weight of the box caused him to burst a

blood vessel. In the 28th Annual Report of the Royal Scottish Academy,

dated Nov. 14 of that year, the Council thus alludes to his merits and

decease:

“A vacancy has occurred in the list of academicians, by the premature

and lamented death of their highly talented brother academician, Patric

Park, Esq., sculptor, an event which occurred suddenly at Warrington, on

the 16th August last. Mr. Park had, at the time of his decease, only

attained the age of forty-four years, and being an enthusiastic student

and lover of his profession, his works, especially his portrait busts –

long distinguished by some of the highest qualities of his noble art,

seemed every succeeding year to gain in strength and refinement, so

that, had life been spared, many works of still higher excellence might

have been looked for from his prolific studio. The Academy exhibitions,

for a long series of years past, and none of them more strikingly than

that of 1855, when his fine bust of the Emperor of the French occupied a

place of honour, sufficiently attest the justice of this brief eulogium

of the council, and justify their sorrow that, in the death of Patric

Park, the Academy has lost one of its most talented members, and the

department of sculpture, in which he more peculiarly excelled, one of

its most eminent professors.”

He married a daughter of Robert Carruthers, Esq., Inverness, and had 4

sons and a daughter. |