MCNEILL,

the name of a clan of the Western isles, which, like the Macleods,

consisted of two independent branches, the Macneills of Barra and

the Macneills of Gigha, said to be descended from brothers. Their

badge was the seaware, but they had different armorial bearings, and

from this circumstance, joined to the fact that they were often

opposed to each other in the clan fights of the period, and that the

Christian names of the one, with the exception of Neill, were not

used by the other, Mr. Gregory thinks the tradition of their common

descent erroneous. Part of their possessions were completely

separated, and situated at a considerable distance from the rest.

The clan Neill were among the secondary vassal tribes of the

lords of the Isles, and its heads appear to have been of Norse of

Danish origin. Buchanan of Auchmar styles them Irish Celts of the

O’Neil tribe, and they are classed by Skene under the Siol

Gillevray, or race of Gillebride, surnamed king of the Isles,

who lived in the 12th century, and derived his descent

from a brother of Suibne, the ancestor of the Macdonalds.

About the beginning of the 15th century, the

Macneills were a considerable clan in Knapdale, Argyleshire. As this

district was not then included in the sheriffdom of Argyle, it is

probable that their ancestor had consented to hold his lands of the

crown.

The first of the family on record is Nigellus Og, who obtained

from Robert Bruce a charter of some lands in Kintyre. His

great-grandson, Gilleonan Roderick Muchard McNeill, in 1427,

received from Alexander, lord of the Isles, a charter of that

island, one of the Hebrides, eight miles long and two to four in

breadth. In the same charter were included the lands of Boisdale in

South Uist, which lies about eight miles distant from Barra. With

John Garve Maclean he disputed the possession of that island, and

was killed by him in Coll. His grandson, Gilleonan, took part with

John, the old lord of the Isles, against his turbulent son, Angus,

and fought on his side at the battle of the Bloody Bay, where he

narrowly escaped falling into the hands of the victorious Clandonald.

He was chief of this sept of division of the Macneills in 1493, at

the forfeiture of the lordship of the Isles.

The Gigha Macneills are supposed to have sprung from Torquil

McNeill, designated in his charter, “filius Nigelli,” who, in the

early part of the 15th century, received from the lord of

the Isles a charter of the lands of Gigha and Taynish, with the

constabulary of Castle Sweyn, in Knapdale. He had two sons, Neill

his heir, and Hector, ancestor of the family of Taynish. Malcolm

McNeill of Gigha, the son of Neill, who is first mentioned in 1478,

was chief of this sept of the Macneills in 1493. After that period

the Gigha branch followed the banner of Macdonald of Isla and

Kintyre, while the Barra Macneills ranged themselves under that of

Maclean of Dowart.

On the insurrection of the islanders, under Donald Dubh, in

the beginning of the 16th century, Gilleonan McNeill of

Barra was amongst the chiefs who, in 1504, were summoned to answer

for their treasonable support given to the rebels, and the following

year, when the Dowart Macleans sent in their submission to the

government, the Macneills of Barra, as their followers, as a matter

of course, did the same.

In 1545 Gilliganan McNeill of Barra was one of the barons and

council of the Isles who accompanied Donald Dubh, styling himself

lord of the Isles and earl of Ross, to Ireland, to swear allegiance

to the king of England. His elder son, Roderick or Ruari McNeill,

was killed at the battle of Glenlivet, by a shot from a fieldpiece,

on 3d Oct. 1594. He left three sons, Roderick, his heir, called

Ruari the turbulent, John, and Murdo. The two latter were among the

eight hostages left by Maclean of Dowart, in 1586, in the hands of

his brother-in-law, Macdonald of Dunyveg. During the memorable and

most disastrous feud which happened between the Macleans and the

Macdonalds at this period, and which has already been described, the

Barra Macneills and the Gigha branch of the same clan fought on

different sides.

The Macneills of Barra were expert seamen, and did not scruple

to act as pirates upon occasion. An English ship having been seized

off the island of Barra, by Ruari the turbulent, Queen Elizabeth

complained of this act of piracy. The laird of Barra was in

consequence summoned to appear at Edinburgh, to answer for his

conduct, but as the haughty and high-spirited chiefs of the remoter

isles were, in those days, sometimes very apt to do, even with the

king’s citations, he treated the summons with contempt. All the

attempts made to apprehend his proving unsuccessful, Mackenzie,

tutor of Kintail, undertook to effect his capture by a stratagem

frequently put in practice against the island chiefs when suspecting

no hostile design. Under the pretence of a friendly visit, he

arrived at McNeill’s castle of Chisamil (pronounced Kisimul), the

ruins of which stand on an insulated rock in Castlebay, on the

south-east end of Barra, and invited him and all his attendants on

board his vessel. There they were well plied with liquor, until they

were all overpowered with it. The chief’s followers were then sent

on shore, while he himself was carried a prisoner to Edinburgh.

Being put upon his trial, he confessed his seizure of the English

ship, but pleaded in excuse that he thought himself bound by his

loyalty to avenge, by every means in his power, the fate of his

majesty’s mother, so cruelly put to death by the queen of England.

This politic answer procured his pardon, but his estate was

forfeited, and given to the tutor of Kintail. The latter restored it

to its owner, on condition of his holding it of him, and paying him

sixty merks Scots, as a yearly feu duty. It had previously been held

of the crown. Some time thereafter, Sir James Macdonald of Sleat

married a daughter of the tutor of Kintail, who made over the

superiority to his son-in-law, and it is now possessed by Lord

Macdonald, the representative of the house of Sleat.

The old chief of Barra, Ruari the turbulent, had several sons

by a lady of the family of Maclean, with whom, according to an

ancient practice in the Highlands, he had handfasted, instead

of marrying her. He afterwards married a sister of the captain of

the Clanranald, and by her also he had sons. To exclude the senior

family from the succession the captain of the Clanranald took the

part of his nephews, whom he declared to be the only legitimate sons

of the Barra chief. Having apprehended the eldest son of the first

family, for having been concerned in the piratical seizure of a ship

of Bourdeaux, he conveyed him to Edinburgh for trial, but he died

there soon after. His brother-german, in revenge, assisted by

Maclean of Dowart, seized Neill McNeill, the eldest son of the

second family, and sent him to Edinburgh, to be tried as an actor in

the piracy of the same Bourdeaux ship, and thinking that their

father was too partial to their half brothers, they also seized the

old chief, and placed him in irons. Neill McNeill, called Weyislache,

was found innocent and liberated through the influence of his uncle.

Barra’s elder sons, on being charged to exhibit their father before

the privy council, refused, on which they were proclaimed rebels,

and commission was given to the captain of the Clanranald against

them. In consequence of these proceedings, which occurred about

1613, Clanranald was enabled to secure the peaceable succession of

his nephew to the estate of Barra, on the death of his father, which

happened soon after. (Gregory’s Highlands and Isles, p. 346.)

The island of Barra and the adjacent isles are still possessed

by the descendant and representative of the family of McNeill. Their

feudal castle of Chisamul has been already mentioned. It is a

building of an hexagonal form, strongly built, with a wall above

thirty feet high, and anchorage for small vessels on every side of

it. In one of its angles is a high square tower, on the top of

which, at the corner immediately above the gate, is a hole, through

which the gockman, or watchman, who sat there all night, threw down

stones upon any who might attempt to surprise the gate in the

darkness. Martin, who visited Barra in 1703, in his ‘Description of

the Western Islands,’ says that the Highland Chroniclers or

sennachies alleged that the then chief of Barra was the 34th

lineal descendant from the first McNeill who had held it. He relates

that the inhabitants of this and the other islands belonging to

McNeill were in the custom of applying to him for wives and

husbands, when he named the persons most suitable for them, and gave

them a bottle of strong waters for the marriage feast.

_____

The chief of the Macneills of Gigha, in the first half of the

16th century, was Neill McNeill, who was killed, with

many gentlemen of his tribe, in 1530, in a feud with Allan Maclean

of Torlusk, called Alein nan Sop, brother of Maclean of

Dowart. His only daughter, Anabella, made over the lands of Gigha to

her natural brother, Neill. The latter was present, on the English

side, at the battle of Ancrum-Moor, in 1544, but it is uncertain

whether he was there as an ambassador from the lord of the Isles, or

fought in the English ranks at the head of his clansmen. He sold

Gigha to James Macdonald of Isla in 1554, and died without

legitimate issue in the latter part of the reign of Queen Mary.

On the extinction of the direct male line, Neill McNeill vic

Eachan, who had obtained the lands of Taynish, became heir male of

the family. His descendant, Hector McNeill of Taynish, purchased in

1590, the island of Gigha from John Campbell of Calder, who had

acquired it from Macdonald of Isla, so that it again became the

property of a McNeill. The estates of Gigha and Taynish were

possessed by his descendants till 1780, when the former was sold to

McNeill of Colonsay, a cadet of the family.

The representative of the male line of the Macneills of

Taynish and Gigha, Roger Hamilton McNeill of Taynish, married

Elizabeth, daughter and heiress of Hamilton Price, Esq. of Raploch,

Lanarkshire, with whom he got that estate, and assumed, in

consequence, the name of Hamilton. His descendants are now

designated of Raploch.

The principal cadets of the Gigha Macneills, besides the

Taynish family, were those of Gallochallie, Carskeay, and Tirfergus.

Torquil, a younger son of Lachlan McNeill Buy of Tirfergus, acquired

the estate of Ugadale in Argyleshire, by marriage with the heiress

of the Mackays in the end of the 17th century. The

present proprietor spells his name Macneal. From Malcolm Beg

McNeill, celebrated in Highland tradition for his extraordinary

prowess and great strength, son of John Oig McNeill of Gallochallie,

in the reign of James VI., sprung the Macneills of Arichonan.

Malcolm’s only son, Neill Oig, had two sons, John, who succeeded

him, and Donald McNeill os Crerar, ancestor of the Macneills of

Colonsay, now the possessors of Gigha. Many cadets of the Macneills

of Gigha settled in the north of Ireland.

Both branches of the clan Neill laid claim to the chiefship.

According to tradition, it has belonged, since the middle of the 16th

century, to the house of Barra. Under the date of 1550, a letter

appears in the register of the privy council, addressed to “Torkill

McNeill, chief and principal of the clan and surname of Macneilis.”

Mr. Skene conjectures this Torkill to have been the hereditary

keeper of Castle Sweyn, and connected with neither branch of the

Macneills. He is said, however, to have been the brother of Neill

McNeill of Gigha, killed in 1530, as above mentioned, and to have,

on his brother’s death, obtained a grant of the non-entries of Gigha

as representative of the family. If this be correct, according to

the above designation, the chiefship was in the Gigha line. Torquil

appears to have died without leaving any direct succession.

_____

The first of the family of Colonsay, Donald McNeill of Crerar

in South Knapdale, exchanged that estate in 1700, with the duke of

Argyle, for the islands of Colonsay and Oronsay. The old possessors

of these two islands, which are only separated by a narrow sound,

dry at low water, were the Macduffies or Macphies (see MACPHIE).

Donald’s great-grandson, Archibald McNeill of Colonsay, sold that

island to his cousin, John McNeill, who married Hester, daughter of

Duncan McNeill of Dunmore, and had six sons. His eldest son,

Alexander, younger of Colonsay, became the purchaser of Gigha. Two

of his other sons, Duncan and Sir John McNeill, have distinguished

themselves, the one as a lawyer and judge, and the other as a

diplomatist.

Duncan, the second son, born in Colonsay in 1794, after being

educated at the universities of St. Andrews and Edinburgh, was

admitted advocate at the Scottish bar in 1816. In 1824 he was

appointed sheriff of Perthshire, and in November 1834,

solicitor-general for Scotland, which office he held till the

following April, and again from September 1841 to October 1842. At

the latter date he was appointed lord-advocate, and continued so

till July 1846. He was elected dean of the faculty of advocates, and

in May 1851 was raised to the bench as a lord of session and

justiciary, when he assumed the title of Lord Colonsay. In May 1852

he was appointed lord-justice-general and president of the court of

session, and in the following year was sworn in a privy councillor.

He was M.P. for Argyleshire from 1843 to 1851.

Sir John McNeill, G.C.B., and F.R.S.E., the third son, was

born at Colonsay in 1795, and in his 19th year graduated

M.D. at the university of Edinburgh. He practised for some time in

the East, as a physician, and in 1831 was appointed assistant envoy

at the court of Persia. In 1834 he became secretary of the embassy,

and received the Persian order of the Lion and Sun, and in June 1836

was appointed envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to

that court. In 1839 he was created a civil knight grand cross of the

order of the Bath. During his residence in Persia he became

thoroughly acquainted with the habits, policy, and resources of the

Asiatic nations; and was enabled, even at that period, to point out

the aggressive designs of Russia with singular penetration and

ability. In 1844 he returned home, and soon after he was placed at

the head of the board appointed to superintend the working of the

new Scottish Poor law act of 1845. In 1851 he conducted a special

inquiry into the condition of the Western Highlands and Islands. In

February 1855 he was chosen by the government of Lord Palmerston to

preside over the commission of Inquiry into the administration of

the supplies of the army in the Crimea. In 1857, he was sworn of the

privy council, and on April 22, 1861, he received the degree of

LL.D. from the University of Edinburgh. He is also Doctor of Civil

Law in the University of Oxford.

MACNEIL, HECTOR,

a popular poet and song-writer, descended from a respectable family

in the West Highlands, was born October 22, 1746, at Rosebank, on

the Esk, near Roslin, Mid Lothian, where his father, at one period

an officer in the army, had taken a farm. He was educated at the

grammar school of Stirling, under Dr. David Doig, to whom he

dedicated his ‘Will and Jean.’ He subsequently attended some classes

at Glasgow, in the higher branches of education. At the age of 14 he

went to Bristol, to a cousin, formerly a West Indian captain, who

sent him on a voyage to the island of St. Christopher’s, furnished

with a letter to a mercantile house there. On his arrival, he

obtained a situation in the counting-house of the merchant to whom

he had been recommended, but having forgot himself so far as to

snatch a kiss from the wife of his employer, one day while reading

in the garden with her, he was soon dismissed. He remained for many

years in the West Indies, but never could rise above subordinate

situations. During this period, it is said, he was employed as a

negro-driver, and in 1788 he published a pamphlet in defence of the

system of slavery in the West Indies, which was for ever abolished

by the Emancipation act of 1830.

When upwards of forth years of age, Macneil returned to

Scotland in bad health and in anything but prosperous circumstances.

He had, when a boy of eleven years of age, written a species of

drama, in imitation of Gay, but his poetical powers seem to have

been allowed to remain almost dormant during his long and struggling

career in the West Indies. He now, however, began “to give the world

assurance” of his possessing “the vision and the faculty divine,” by

publishing, in the spring of 1789. ‘The Harp, a Legendary Tale, in

two parts,’ which brought him into favourable notice in literary

society, but added nothing to his income.

Having no prospect of employment in his native country, he

again quitted it, but this time for the East Indies. Disappointed,

however, in his expectations there, he soon returned to Scotland,

and took up his abode in a cottage near St. Ninians, in the

immediate neighbourhood of Stirling. During his sojourn in the East,

he visited the celebrated caves of Elephanta, Cannara, and Ambola,

of which a detailed account written by him, was published in the

eighth volume of the Archaeologia. He afterwards wrote a number of

love songs in the Scottish language, which speedily became

favourites with all classes. Of these, his ‘Mary of Castlecary,’ ‘I

loo’d ne’er a laddie but ane,’ ‘Come under my plaidie,’ and others,

nearly all of a dramatic nature and in the dialogue form, are

familiar to all lovers of Scottish song.

In 1795 appeared his principal poem, ‘Scotland’s Skaith, or

the History of Will and Jean, ower true a tale,’ the object of which

was to exhibit the evils attendant on an inordinate use of ardent

spirits, in the story of a once industrious rustic and his wife

reduced through intemperance to poverty and distress; and so great

was its popularity that in less than twelve months it had passed

through fourteen editions. It was followed in the ensuing year, by a

sequel, entitled ‘The Waes o’War.’ All his pieces are in the

Scottish dialect.

In consequence of continued bad health, in 1796, with the hope

of deriving benefit from a tropical climate, to which he had been so

long used, and also of bettering his circumstances, he was induced

to go out to Jamaica, and on the eve of his departure composed his

descriptive poem, entitled ‘The Links of forth, or a parting Peep at

the Carse of Stirling,’ which was published in 1799. At Jamaica he

remained for a year and a half, residing with Mr. John Graham of

Three-Miles-River, where he wrote ‘The Scottish Muse,’ which

appeared in 1809. On the death of that gentleman he left Macneil an

annuity of £100.

In 1800 Macneil returned to Scotland, and having now a

competence and leisure to attend to literary pursuits, he took up

his abode at Edinburgh, where he mixed in good society. The same

year he published, anonymously, a novel, entitled ‘The Memoirs of

Charles Macpherson,’ which is understood to contain an account of

his own early career. Soon after, he set about preparing a complete

collection of his poetical works, which appeared in two volumes, in

1801. He next published two works in verse, entitled ‘Town Fashions,

or Modern Manners Delineated,’ and ‘Bygane Times and Late-come

Changes,’ and in 1812, a novel in two volumes, styled ‘The Scottish

Adventurers, or the Way to Rise,’ in all of which he eulogises the

manners and habits of past times, in preference to what he deemed

modern innovations and corruptions. Many minor pieces he inserted in

the Scots Magazine, of which he was at one time editor. He died at

Edinburgh of jaundice, 15th March 1818. The statement in

Chambers’ ‘Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen,’ that he was

in such destitute circumstances at the time of his death that he did

not leave “wherewithal to defray his funeral expenses,” is not

correct.

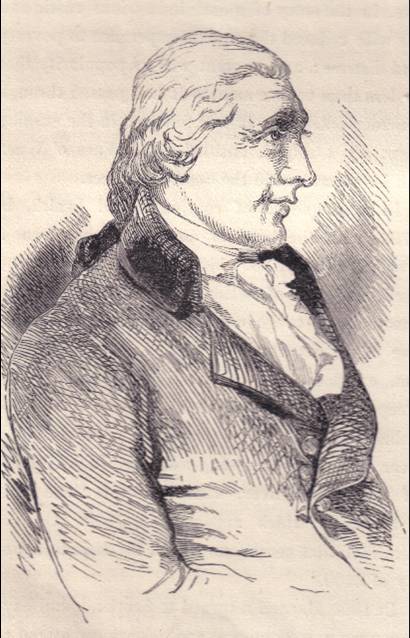

The portrait of Mr. Macneil is subjoined;

[portrait of Hector Macneil]

He is described, towards the close of his life, as having been a

tall, fine-looking old man, with a very sallow complexion, and a

dignified and somewhat austere expression of countenance. Like all

persons who have made poetry their profession, and felt the

struggles and privations attendant on the exclusive service of the

muses, he invariably warned all young aspirants for poetic fame

against embarking in the precarious occupation of authorship. His

works are:

On the Treatment of the Negroes in Jamaica. 1788, 8vo.

The Harp; a Legendary Tale. Edin. 1789, 4to.

Scotland’s Skaith, or the History of Will and Jean; owre true

a Tale. Together with some additional Poems. Embellished with

elegant engravings. 2d edit. Edin. 1795, 8vo. Again, entitled,

Politicks, or the History of Will and Jean; a Tale for the Times.

1796, 4to.

The Waes of War; or, The Upshot of the History of Will and

Jean. Edin. 1796, 8vo. Lond. 1796, 4to.

The Links o’ Forth; or, a Parting Peep at the Carse of

Stirling. Edin. 1795, 8vo.

Poetical Works, Lond. 1801, 2 vols, 8vo. 1806, 2 vols, 12mo.

3d edit. 1812.

The Pastoral, or Lyric Muse of Scotland; in 3 cantos. 1809.

4to.

Bygane Times and late-come changes, or a Bridge-Street

Dialogue in Scottish verse, exhibiting a Picture of the Existing

Manners, Customs, and Morals. 3d edit. 1812.

Scottish Adventurers, or the Way to Rise; an Historical Tale.

1812, 2 vols. 8vo.

An Account of the Caves of Cannara, Ambola, and Elephanta, in

the East Indies; in a Letter from Hector Macheill, Esq., then at

Bombay, to a friend in England, Archaeol. viii. 251. 1787.