GOW,

a surname derived from a Gaelic word signifying Smith. Cowan, when not

a modulation of Colquhoun, is the same word as Gowan, and has the same

meaning. The surname M’Gowan is the English Smithson. “The Gows,” says

Lower, in his Essay of English Surnames, (vol. I. P. 104), “were once

as numerous in Scotland as the Smiths in England, and would be so at

this time had not many of them, at a very recent date, translated the

name to Smith.”

GOW, NEIL,

renowned for his skill in playing the violin, of humble origin, was

born at Inver, near Dunkeld, Perthshire, March 22, 1727. He early

displayed a taste for music, and was almost entirely self-taught till

about his thirteenth year, when he received some instructions from

John Cameron, an attendant of Sir George Stewart of Grandtully. His

progress as a musician was singularly rapid. A public trial having

been proposed amongst a few of the best performers in that part of the

country, young Neil was prevailed on to engage in the contest, when

the prize was decreed to him, the judge, who was blind, declaring that

“he could distinguish the stroke of Neil’s bow among a hundred

players.” Having obtained the notice, first, of the Athol family, and

afterwards of the duchess of Gordon, he was soon introduced to the

admiration of the fashionable world, and enjoyed the countenance and

distinguished patronage of the principal nobility and gentry of

Scotland till his death. As a performer on the violin he was

unequalled. “The livelier airs,” says Dr. M’Knight, in the Scots

Magazine for 1809, “which belong to the class of what are called the

strathspey and reel, and which have long been peculiar to the northern

part of the island, assumed in his hand a style of spirit, fire, and

beauty, which had never been heard before. There is perhaps no species

whatever of music executed on the violin, in which the characteristic

expression depends more on the power of the bow, particularly in what

is called the upward or returning stroke, than the Highland reel.

Here, accordingly, was Gow’s forte. His bow-hand, as a suitable

instrument of his genius, was uncommonly powerful; and where the note

produced by the up-bow was often feeble and indistinct in other hands,

it was struck in his paying with a strength and certainty which never

failed to surprise and delight the skilful hearer. To this

extraordinary power of the bow, in the hand of this great original

genius, must be ascribed the singular felicity of expression which he

gave to all his music, and the native Highland gout of certain

tunes, such as ‘Tullochgorum,’ in which his taste and style of bowing

could never be exactly reached by any other performer. We may add the

effect of the sudden shout with which he frequently accompanied his

playing in the quick tunes, and which seemed instantly to electrify

the dancers, inspiring them with new life and energy, and rising the

spirits of the most inanimate.”

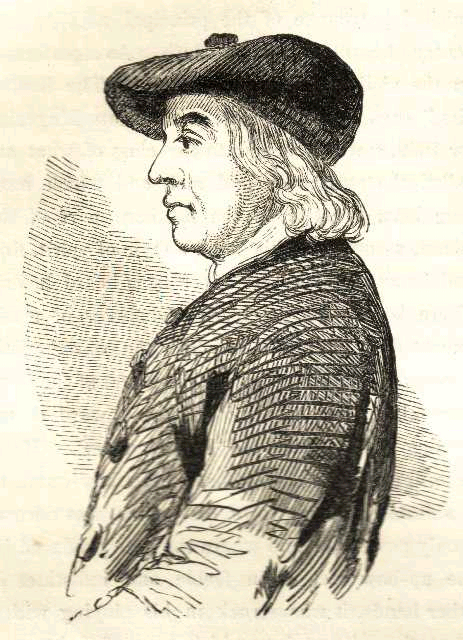

Neil Gow

excelled also in the composition of Scottish melodies; and his sets of

the older tunes, and various of his own airs, were prepared for

publication by his son Nathaniel. In private life Neil Gow was

distinguished by his unpretending manners, his homely humour, strong

good sense and knowledge of the world. His figure was vigorous and

manly, and the expression of his countenance spirited and intelligent.

His whole appearance exhibited so characteristic a model of a Scottish

Highlander, that his portrait was at one period to be found in all

parts of the country. A woodcut of it is subjoined:

[portrait of Neil Gow]

Four admirable

likenesses of him were painted by the late Sir Henry Raeburn, one for

the County Hall, Perth, and the others for the duke of Athol, Lord

Gray, and the Hon. William Maule, created in 1831 Lord Panmure. His

portrait was also introduced into the view of a ‘Highland Wedding,’ by

Mr. Allan, with that of Donald Gow, his brother, who usually

accompanied him on the violoncello.

Neil Gow

died at Inver, March 1, 1807, in the 80th year of his age.

He was twice married: first, to Margaret Wiseman, by whom he had five

sons and three daughters; and secondly to Margaret Urquhart, but had

no issue by her. Three sons and two daughters predeceased him, and

besides Nathaniel, the subject of the following notice, he left

another son, John, who long resided in London, as leader of the

fashionable Scottish bands there, and died in 1827.

GOW, NATHANIEL,

an eminent violin player, teacher, and composer of music, the youngest

son of the preceding, was born at Inver, near Dunkeld, May 28, 1766.

Having exhibited early indications of a talent for music, his father

soon began to give him instructions on the violin; and afterwards sent

him to Edinburgh, where he studied first under M’Intosh, and

subsequently under M’Glashan, at that period two well known

violinists, and the latter especially an excellent composer of

Scottish airs. He took lessons on the violoncello from Joseph Reneagle,

afterwards professor of music at Oxford. In 1782 he was appointed one

of his majesty’s trumpeters for Scotland, and on the death of his

elder brother, William, in 1791, he succeeded him as leader of the

band formerly conducted by M’Glashan at Edinburgh, a situation which

he held for nearly forty years with undiminished reputation.

In 1796 he

and Mr. William Shepherd entered into partnership in Edinburgh, as

music-sellers, and the business was continued till 1813, when, on the

death of the latter, it was given up. He afterwards resumed it, in

company with his son Neil, the composer of ‘Bonny Prince Charlie,’ and

other beautiful melodies, who died in 1823. The business was finally

relinquished in 1728, having involved him in losses, which reduced him

to a state of bankruptcy.

Between 1799

and 1824 Nathaniel Gow published his six celebrated collections of

Reels and Strathspeys; a Repository of Scots Slow Airs, Strathspeys,

and Dances, in 4 vols.; Scots Vocal Melodies, 2 vols.; a collection of

Ancient Curious Scots Melodies, and various other pieces, all arranged

by himself. In some of the early numbers he was assisted by his

father, and these came out under the name of Neil Gow and Son.

During the

long period of his professional career, his services as conductor were

in constant request at all the fashionable parties that took place

throughout Scotland; and he frequently received large sums for

attending with his band at country parties. He was a great favourite

with George the Fourth, and on his visits to London had the honour of

being invited to play at the private parties of his majesty, when

prince of Wales, at Carlton House. Such was the high estimation in

which he was held by the nobility and gentry of his native country,

that his annual balls were always most numerously and fashionably

attended; and among the presents which at various times were made to

him were, a massive silver goblet, in 1811, from the earl of

Dalhousie; a fine violoncello by Sir Peter Murray of Ochtertyre; and a

valuable violin by Sir Alexander Don of Newton Don, baronet. As a

teacher of the violin and piano-forte accompaniment he was paid the

highest rate of fees, and he had for pupils the children of the first

families in the kingdom.

In March

1827 he was compelled, by his reduced circumstances, and while

suffering under a severe illness, to make an appeal to his former

patrons and the public for support, by a ball, which produced him

about £300, and which was continued annually for three years. The

noblemen and gentlemen of the Caledonian Hunt were not unmindful of

the merits of one who had done so much for the national music of

Scotland, as they voted him, on his distresses becoming known, £50

yearly during his life; and he every year received a handsome present

from the Hon. William Maule, subsequently Lord Panmure. He died

January 17, 1831, aged 65. He was twice married: first, to Janet

Fraser, by whom he had five daughters and one son; and, secondly, in

1814, to Mary Hogg, by whom he had three sons and two daughters; one

of whom, Mary, was married to Mr. Jenkins, London; another, Jessie,

was the wife of Mr. Luke, treasurer of George Heriot’s Hospital; and a

third, Augusta, became a teacher of music.