GARDINER, JAMES,

a distinguished military officer, celebrated as much for his piety as

for his courage and loyalty, the son of Captain Patrick Gardiner, of the

family of Torwoodhead, by Mrs. Mary Hodge, of the family of Gladsmuir,

was born at Carriden, Linlithgowshire, January 10, 1687-8, and received

his education at the grammar school of Linlithgow. He served as a cadet

very early, and at fourteen years of age had an ensign’s commission in a

Scots regiment in the Dutch service, in which he continued till 1702,

when he received an ensign’s commission from Queen Anne. At the battle

of Ramillies, May 23, 1706, he was wounded and taken prisoner, but was

soon after exchanged. In the latter year, he obtained the rank of

lieutenant, and on January 31, 1714-15, was made captain-lieutenant in

Colonel Ker’s regiment of dragoons. At the taking of Preston in

Lancashire, in 1715, he headed a party of twelve, and advancing to the

barricades of the insurgents, set them on fire, in spite of a furious

storm of musketry, by which eight of his men were killed. He afterwards

became aide-de-camp to the earl of Stair, and accompanying his lordship

in his celebrated embassy to Paris, acted as master of the horse on

occasion of his splendid entrance into the French capital. After several

intermediate promotions, he was, July 20, 1724, appointed major of a

regiment of dragoons, commanded by his friend Lord Stair; and in January

1730, he was advanced to the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the same

regiment, in which he continued till April 1743, when he received a

colonel’s commission in another dragoon regiment then newly raised,

which was quartered in the neighbourhood of his own house in East

Lothian.

Colonel

Gardiner had for many years been noted for his gay and dissolute habits

of life, but about the middle of July 1719 a remarkable change took

place in his conduct and sentiments, caused by his accidental perusal of

a religious book, written by Mr. Thomas Watson, entitled ‘The Christian

Soldier, or Heaven taken by storm.’ The account of his wonderful

conversion as given by Dr. Doddridge, in his celebrated memoir of him,

which partakes of the character of the early miracles of the church, is

well known. He was, says his biographer, in the most amazing manner,

without any religious opportunity, or peculiar advantage, deliverance,

or affliction, reclaimed, on a sudden, in the prime of his days and the

vigour of health, from a life of profligacy and wicked ness, not only to

a steady course of regularity and virtue, but to high devotion and

strict though unaffected purity of manners; which he continued to

sustain until his untimely death.

On the

breaking out of the Rebellion in 1745 his regiment marched with the

utmost expedition to Dunbar, and being joined by Hamilton’s regiment of

dragoons, and the foot under the command of Sir John Cope, the whole

force proceeded towards Edinburgh, to give battle to the rebels. The two

hostile bodies came into view of each other on September 20, in the

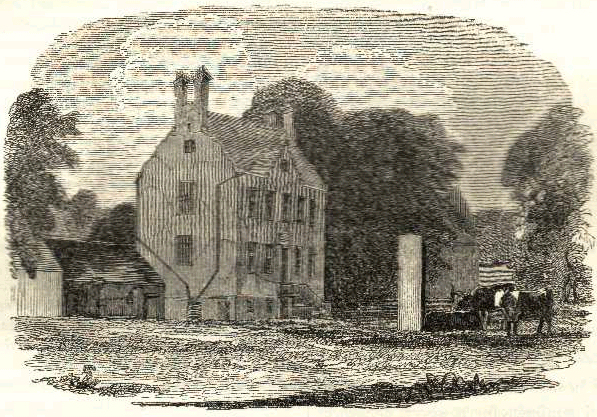

neighbourhood of Colonel Gardiner’s own house of Bankton near

Prestonpans, of which the following, sketched by Mr. J.C. Brown in 1844,

is a representation. It was totally destroyed by fire on 27th

November, 1852.

[pic of Gardiner’s home]

On the 21st he fell at the battle of Prestonpans. At the

beginning of the action he received a wound by a bullet in his left

breast, and soon after received a shot in his right thigh. After a faint

fire, his regiment was seized with a panic, and took to flight; at the

same moment he saw a party of infantry who were bravely fighting near

him, without an officer to head them, on which he said, “These brave

fellows will be cut to pieces for want of a commander,” and riding up to

them, he cried out, “Fire on, my lads, and fear nothing.” But just as

the words were spoken, he was cut down by a Highlander with a scythe

fastened to a long pole, and immediately after, being dragged off his

horse, another Highlander gave him a stroke, either with a broadsword or

a Lochaber axe, on the back part of his head, which was the mortal blow.

His remains were interred on the 24th of the same month at

the parish church of Tranent, where he usually, when at home, attended

divine service. He had married, July 11, 1726, the Lady Frances Erskine,

daughter of the fourth earl of Buchan, by whom he had thirteen children,

five only of whom, two sons and three daughters, survived their father.

One of his daughters, named Richmond, married Mr. Laurence Inglis,

depute-clerk of Bills at Edinburgh. She was the subject of a song of Sir

Gilbert Elliot’s, ‘Fanny fair, all woe-begone,’ which was originally set

to the tune of Barbara Allan. She herself wrote poetry, and in 1781

published at Edinburgh, in a quarto volume, ‘Anna and Edgar, or Love and

Ambition, a Tale.’ She died at Edinburgh, 9th June 1795.