|

ELLIOT, ELIOT, or

ELLIOTT, a

surname of considerable antiquity both in Scotland and England, possessed

by a border clan which resided chiefly in the eastern districts of the

border. Willis, the antiquary, mentions persons of this name having been

seated in Devonshire about the reign of King John, and having branched out

into several families, chiefly in the west of England, some of them being

of importance in the reign of Edward the First. Of the same stock is

descended the family of Eliot of Port Eliot in Cornwall, settled there

about 1540. There were also families of this name in Suffolk and Surrey.

The Scottish

Elliots appear to have been originally settled on the river and village of

Eliot of Elot, in Forfarshire, hence the word Arbirlot, a contraction of

Aber-Eliot, the river entering the sea at the parish of that name. As most

of the surnames in Scotland were local, it is probable, and this has ever

been the opinion of the Elliots themselves, that they had their name from

this river. During the reign of Robert the Third, about the year 1395,

they were induced to remove, in a body, into Liddesdale, by means of the

family of Douglas, to strengthen their interest on the borders, towards

England.

Eliott of

Lariston, in Liddesdale, was unquestionably the original stock from which

all of the name in Scotland, at least, are descended. The direct male line

failed about the beginning of the eighteenth century, and the heir female

was married to James Elliot of Redheugh, youngest son of the family of

Stobs or Stobhouse, in Roxburghshire, who continued the line, and appears

to have been the parent stock of those branches which have in modern times

rendered themselves eminent.

His son, or

grandson, was Gilbert Elliot of Stobs, commonly called “Gibby wi’ the

gouden gartins.” He married Margaret, daughter of Walter Scott of Harden,

known by the name of ‘Maggy Fendy,” and had by her six sons, namely,

William, his heir; Gilbert, of Craigend; Archibald, of Middlestead; Gavin,

of Grange, ancestor of the family of Midlem or Middlemill and Lord Minto

(see below); John, of Godistree; and James, of Redheugh, who married the

heiress of Lariston, as above stated.

The eldest son,

William Elliot of Stobs, by his wife, Elizabeth, daughter of Sir James

Douglas of Conons, had three sons, and of the youngest, William, Sir John

Elliot of Peebles, baronet, an eminent physician of London, of whom a

memoir is afterwards given, was heir male.

The eldest son,

Sir Gilbert Elliot of Stobs, was for his distinguished bravery made a

knight banneret in 1643, by King Charles the First in person. He was

afterwards, on 3d September 1666, created a baronet of Nova Scotia. He was

twice married. By his first wife, Isabella, second daughter of James,

master of Cranstoun, he had an only son, William; and by his second wife,

Magdaline, daughter of Sir Thomas Nicholson of Lasswade, baronet, he had

two sons and a daughter.

His eldest son,

Sir William, second baronet, died in 1694. Sir William’s son, Sir Gilbert,

third baronet, married Eleanor, daughter of William Elliot of Wells, in

Roxburghshire, by whom he had eight sons, the youngest of whom, George

Augustus, the celebrated General Elliot, was created Lord Heathfield for

his gallant defence of Gibraltar in 1787, a memoir of whom is given below.

Sir Gilbert died in 1764. His son, grandson, and great-grandson, all

succeeded to the title and estates. The latter, Sir William, sixth

baronet, by his wife, daughter of John Russell, Esq. of Roseburn, had

eight sons and two daughters, and died 14th May 1812. His

eldest son, Sir William Francis Elliot of Stobs and Wells, seventh

baronet, F.R.S., and deputy-lieutenant of Roxburghshire, married, 22d

March, 1826, the only daughter of Sir Alexander Roswell of Auchinleck,

baronet, and by her (who died in 1836) has issue. In 1818 he succeeded his

cousin, the late Right Hon. William Elliot, M.P. for Peterborough, in the

estate of Wells and othee3r lands in Roxburghshire, the second Lord

Heathfield, on whom the estates were entailed, having previously died

without issue.

_____

GILBERT ELLIOT,

popularly called ‘Gibbie Elliot,’ an eminent lawyer and judge, the founder

of the Minto family, was a younger son of Gawin Elliot of Midlem Mill,

above mentioned. He was born in 1651, and being educated for the

profession of the law, he at first acted only as a writer in Edinburgh, in

which capacity he was agent for the celebrated preacher, Mr. William

Veitch, and was successful in getting the sentence of death passed against

the latter commuted to banishment, in the year 1679. His own zeal for the

presbyterian cause and religious liberty caused him to be denounced by the

Scottish privy council, and 16th July, 1685, he was condemned

for treason, and forfeited for being in arms with the earl of Argyle. He

was soon, however, pardoned by the king, and in 1687 he applied to be

admitted advocate. He was one of the Scottish deputation to the prince of

Orange in Holland, to concert measures for bestowing on him the British

crown. At the Revolution the act of forfeiture against him was rescinded,

and he was appointed clerk to the privy council, which office he held till

1692. He was created a baronet in 1700, and was constituted a lord of

session, and took his seat as Lord Minto, in 1705. At the same time he

became a lord of justiciary. He died in 1718, at the age of 67.

The estate of

Minto in Roxburghshire, which originally belonged to the Turnbulls, he had

purchased some time before his elevation to the bench, from the daughters,

who were co-heiresses, of the last possessor, Walter Riddell, Esq., second

son of Walter Riddell of Newhouse. From King William he had a charter of

the lands and barony of Headshaw and Dryden.

Dr. M’Crie, in

his ‘Life of Veitch,’ relates the following amusing anecdote regarding

this eminent personage and his former client. “When Lord Minto visited

Dumfries, of which Mr. Veitch was minister after the Revolution, he always

spent some time with his old friend, when their conversation often turned

on the perils of their former life. On these occasions his lordship was

accustomed facetiously to say, ‘Ah! Willie, Willie had it no been for me,

the pyets had been pyking your pate on the Nether-Bow port!’ to which

Veitch would reply, ‘Ah! Gibbie, Gibbie, had it no been for me, ye would

hae been yet writing papers for a plack the page.’”

His son, Sir

Gilbert Elliot, the second baronet, was born in 1693 or 1694. He became a

lord of session 4th June 1726, when he also assumed the

judicial title of Lord Minto, a lord of justiciary 13th

September 1733, and was afterwards appointed lord justice clerk. He

likewise sat in parliament in 1725. Concurring in politics with the

celebrated John duke of Argyle and Greenwich, he was much in that

nobleman’s confidence, and assisted him in the management of Scots

affairs. Besides other improvements, he formed a large library at

Minto-house, such as at that period was rarely to be met with in Scotland.

He died suddenly at Minto in 1766. He is said to have been the first to

introduce the German flute into Scotland about 1725. He married Helen,

daughter of Sir Robert Stuart, baronet of Allanbank, by whom, besides

other children, he had Gilbert, the third baronet, and his sister, Miss

Jane Elliot, authoress of the ‘Flowers of the Forest,’ a memoir of whom is

given below.

Sir Gilbert,

third baronet, author of the beautiful pastoral, beginning, “My sheep I’ve

forsaken and broke my sheep-hook,” was born in September 1722. Like his

father and grandfather, he was educated for the bar, and passed advocate

10th December, 1743. He married, 15th December,

1746, Agnes Murray Kynnynmound, heiress of Melgund in Forfarshire and of

Kynnynmound in Fifeshire, by whom he had a son, the first earl of Minto,

of whom a notice follows. The father of this lady was Hugh Dalrymple,

second son of the first baronet of Hailes, who inherited the estates of

Melgund and Kynnynmound in 1736, in right of his mother, Janet, daughter

of Sir James Rocheid of Inverleith and widow of Alexander Murray of

Melgund, and he in consequence assumed the designation of Hugh

Dalrymple-Murray-Kynnynmound. He died in 1741. Sir Gilbert was a man of

considerable political and literary abilities, and filled several high

official situation. In 1754 he was elected member of parliament for

Selkirkshire, and was again returned in 1761. In 1765, on a vacancy

occurring in the representation of Roxburghshire, he resigned his seat for

Selkirkshire, and was returned member for his native county; and also

during the successive parliaments in 1768 and 1774. In 1763 he was

appointed treasurer of the navy. In April 1766 he succeeded his father in

his title and estates, and subsequently obtained the reversion of the

office of keeper of the signet in Scotland. He was also one of the lords

of the admiralty. He died at Marseilles, whither he had gone for the

recovery of his health, in January 1777. His Philosophical Correspondence

with David Hume is quoted with commendation by Dugald Stewart, in his

‘Philosophy of the Human Mind,’ and in his ‘Dissertation’ prefixed to the

seventh edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. Sir Gilbert was the writer

of some pathetic elegiac verses on Colonel Gardiner, who fell at Preston,

beginning, “Twas at the hour of dark midnight.” He is also supposed to

have been the author of some beautiful lines in blank verse, entitled

‘Thoughts occasioned by the Funeral of the Earl and Countess of

Sutherland, at the Abbey of Holyrood House,’ 9th July, 1766,

inserted in the Scots Magazine for October of that year, where they are

attributed to a person of distinction.

His eldest son,

Gilbert Elliot Murray Kynnynmond, fourth baronet, and first earl of Minto,

a distinguished statesman, was born April 23, 1751. After receiving part

of his education at a school in England, in 1768 he was sent to Christ

Church, Oxford. He subsequently entered at Lincoln’s Inn, and was in due

time called to the bar. He afterwards visited the Continent, and on his

return was, in 1774, elected M.P. for Morpeth. At first he supported the

Administration, but towards the close of the American war he joined

himself to the opposition, and was twice proposed by his party as Speaker,

but was both times defeated by the ministerial candidate. In January 1777,

he had married Anna Maria, eldest daughter of Sir George Amyand, Bart.,

and soon after he succeeded his father as baronet. At the breaking out of

the French Revolution, he and many of his friends became the supporters of

the government. In July 1793 he was created by the university of Oxford

doctor of civil laws. The same year he acted as a commissioner for the

protection of the royalists of Toulon, in France. The people of Corsica

having sought the protection of Great Britain, Sir Gilbert Elliot was

appointed governor of that island, and in the end of September 1793 was

sworn in a member of the privy council. Early in 1794 the principal

strongholds of Corsica were surrendered by the French to the British arms;

the king accepted the sovereignty of the island; and on June 19, 1794, Sir

Gilbert, as viceroy, presided in a general convention of Corsican

deputies, at which a code of laws, modelled on the constitution of Great

Britain, was adopted. The French had still a strong party in the island,

who, encouraged by the successes of the French armies in Italy, at last

rose in arms against the British authority. The insurrection at Bastia,

the capital of the island, was suppressed in June 1796; but the French

party gradually acquiring strength, while sickness and diversity of

opinion rendered the situation of the British very precarious, it was

resolved, in September following, to abandon the island. Sir Gilbert

returned to England early in 1797, and in the subsequent October was

raised to the peerage of the United Kingdom as Baron Minto, with the

special distinction accorded him of bearing with his family arms in chief

the arms of Corsica. In July 1799 his lordship was appointed envoy

extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to Vienna, where he remained

till the end of 1801. On the brief occupation of office by the Whigs in

1806, he was appointed president of the Board of Control. He was soon

after nominated governor general of India, and embarked for Bengal in

February 1807. “When Sir Gilbert Elliot,” says Mr. MacFarlane, in his

History of British India, “Lord Minto had been one of the bitterest

enemies of Warren Hastings, and had taken a most active part on the

impeachment and trial of that great man. Like some of his predecessors, he

had gone out to India impressed with the notions that the true policy of

Britain was non-interference, that no attempt ought to be mad to extend

the limits of our possessions or to increase the number of our connections

with the native princes. No man had inveighed more bitterly than he

against the ambitious, encroaching, aggrandizing spirit of Mr. Hastings,

or had dwelt more pathetically on the wrongs done to the native princes.

Yet his lordship had not been many days on the banks of the Hooghly ere he

confessed that the security of our empire depended upon the actual

superiority of our power, upon the sense which the natives entertained of

that power, and upon the submissiveness of our neighbours.” Under his

administration many important acquisitions were made by the British arms.

“If conquests and annexations,” says Mr. MacFarlane, “were not made in

Hindostan, there was no lack of them in other directions. In fact, during

the peaceful administration of Lord Minto, our conquests and

operations in the Eastern Archipelago, or Insular India, were widely

extended – so widely, indeed, that the forces and resources employed in

this direction, would have made it difficult to prosecute any important

war on the Indian continent.” He accompanied in person the successful

expedition against Java in 1811. For his services in India he received the

thanks of parliament, and in February 1813 was created earl of Minto, and

Viscount Melgund. Towards the close of the same year he resigned his

office, and returned to England. His lordship died, June 21st,

1814, at Stevenage, while on his way to Scotland. He had three sons and

three daughters.

His eldest son,

Gilbert, fifth baronet, and second earl of Minto, born in 1782, married in

1806, the eldest daughter of Patrick Brydone, Esq., of Lennel, near

Coldstream, once well-known for his ‘Tour through Sicily,’ by whom he had

issue. He assumed the names of Murray and Kynnynmond by royal license, was

M.P. for Ashburton in 1806-7, and ambassador at Berlin from 1832 to 1834;

privy councillor, 1832; G.C.B., 1834; first lord of the admiralty from

September 1835 to September 1841, and lord privy seal from July 1846 to

Feb. 1852, and was sent on a mission to Italy and Switzerland in Sept.

1847. The countess died at Nerve, a short distance from Genoa, 21st

July 1853. The earl died in 1859. His eldest son, William Hugh, third

earl, born at Minto castle, Roxburghshire, in 1814, was, while Viscount

Melgund, M.P. for Hythe from 1837 to 1841, for Greenock from 1847 to 1852,

and for Clackmannan from April 1857 to May 1859; chairman of the General

Board of Lunacy for Scotland from 1857 to 1859. He married in 1844,

Emma-Eleanor Elizabeth, born in 1824, daughter of General Sir Thomas

Hislop, Baronet; issue, Gilbert John, Viscount Melgund, and three other

sons.

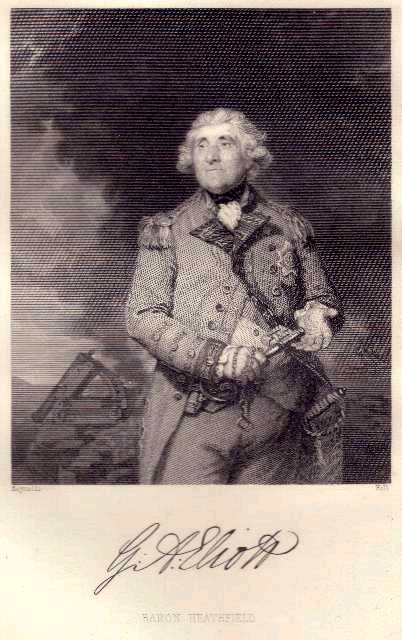

ELLIOT, GEORGE

AUGUSTUS, LORD HEATHFIELD,

the gallant defender of Gibraltar, ninth and youngest son of Sir Gilbert

Elliot, the third baronet of Stobs, in Roxburghshire, by Eleanor, daughter

of William Elliot, Esq. of Wells, was born at Stobs in 1718. He was

educated at home by a private tutor, and afterwards sent to the university

of Leyden, where he made great progress in classical learning. After

attending the French military school of La Fere, in Picardy, he served for

some time as a volunteer in the Prussian army. He returned home in 1735,

and became a volunteer in the 23d regiment of foot, or Royal Welsh

fusileers, then lying in Edinburgh castle, but in 1736 he joined the

engineer corps at Woolwich, where he continued till he was made adjutant

of the second troop of horse grenadiers. In May 1743 he went with his

regiment to Germany, and was wounded at the battle of Dettingen. In this

regiment he successively purchased the commissions of captain, major, and

lieutenant-colonel, when he resigned his commission as an engineer, and

was soon after appointed aide-de-camp to George the Second. In 1759 he

quitted the second regiment of horse guards, being selected to raise,

form, and discipline, the first regiment of light horse, called after him

Elliot’s. He subsequently served, with the rank of brigadier-general, in

France and Germany, from whence he was recalled, and was employed as

second in command in the memorable expedition against the Havannah. At the

peace the king conferred on his regiment the title of royals, when it

became the 15th, or king’s royal regiment of light dragoons. In

1775 General Elliot was appointed commander-in-chief of the forces in

Ireland, from whence, at his own request, he was soon recalled, and sent

to Gibraltar as governor of that important fortress.

In 1779, Spain,

in connection with France, took part in the struggle between Great Britain

and her revolted American colonies, and, even before a declaration of war,

laid siege to Gibraltar by sea and land. That fortress was defended by

General Elliot with consummate skill, during three years of constant

investment by the combined French and Spanish forces. In June 1782, the

duke de Crillon, commander-in-chief of the Spanish army, who had recently

taken the island of Minorca frm the British, arrived at Gibraltar, with a

reinforcement. All the french princes royal were in the camp. An army of

40,000 French and Spaniards were at the foot of the hill. Floating

batteries, with hanging roofs, were constructed to attack the

fortifications, so carefully and strongly built, that neither balls nor

bombs could injure them. Twelve hundred pieces of heavy ordnance were

collected, and the quantity of gunpowder was said to exceed eighty-three

thousand barrels. In Miller’s History of the Reign of George the Third is

the following account of their final discomfiture: “The Thirteenth of

September was fixed upon by the besiegers for making a grand attack, when

the new invented machines, with all the united powers of gunpowder and

artillery in the highest state of improvement, were to be called into

action. The combined fleets of France and Spain in the bay of Gibraltar

amounted to forty-eight sail of the line. Their batteries were covered

with one hundred and fifty-four pieces of heavy brass cannon. The numbers

employed by land and sea against the fortress were estimated at one

hundred thousand men. With this force, and by the fire of three hundred

cannon, mortars, and howitzers, from the adjacent isthmus, it was intended

to attack every part of the British works at one and the same instant. The

surrounding hills were covered with people assembled to behold the

spectacle. The cannonade and bombardment were tremendous. The showers of

shot and shells from the land batteries and the ships of the besiegers,

and from the various works of the garrison, exhibited a most dreadful

scene. Four hundred pieces of the heaviest artillery were playing at the

same moment. The whole peninsula seemed to be overwhelmed in the torrents

of fire which were incessantly poured upon it. The Spanish floating

batteries for some time answered the expectations of their framers. The

heaviest shells often rebounded from their tops, while thirty-two pound

shot made no visible impression upon their hulls. For some hours the

attack and defence were so equally supported, as scarcely to admit of any

appearance of superiority on e3ither side. The construction of the

battering ships was so well-calculated for withstanding the combined force

of fire and artillery, that they seemed for some time to bid defiance to

the powers of the heaviest ordnance. In the afternoon the effects of hot

shot became visible. At first there was only an appearance of smoke, but

in the course of the night, after the fire of the garrison had continued

about fifteen hours, two of the floating batteries were in flames, and

several more were visibly beginning to kindle. The endeavours of the

besiegers were now exclusively directed to bring off the men from the

burning vessels; but in this they were interrupted. Captain Curtis, who

lay ready with twelve gun-boars, advanced and fired upon them with such

order and expedition, as to throw them into confusion before they had

finished their business. They fled with their boats, and abandoned to

their fate great numbers of their people. The opening of daylight

disclosed a most dreadful spectacle. Many were seen in the midst of the

flames crying out for help, while others were floating upon pieces of

timer, exposed to equal danger from the opposite element. The generous

humanity of the victors equalled their valour, and was the more honourable,

as the exertion of it exposed them to no less danger than those of active

hostility. In endeavouring to save th lives of his enemies, Captain Curtis

nearly lost his own. While for the most benevolent purpose he was

alongside of the floating batteries, one of them blew up, and some heavy

pieces of timber fell into his boat and pierced through its bottom. By

similar perilous exertions nearly four hundred men were saved from

inevitable destruction. The exercise of humanity to an enemy under such

circumstances of immediate action and impending danger, conferred more

true honour than could be acquired by the most splendid series of

victories. It is some measure obscured the impression made to the

disadvantage of human nature, by the madness of mankind in destroying each

other by wasteful wars. The floating batteries were all consumed. The

violence of their explosion was such as to burst open doors and windows at

a great distance. Soon after the destruction of the floating batteries,

Lord Howe, with thirty-five ships of the line, brought to the brave

garrison an ample supply of every thing wanted, either for their support

of their defence.” He succeeded in landing two regiments of troops, and in

sending in a supply of fifteen hundred barrels of gunpowder.

So admirable and

complete had been the measures taken by the governor for the protection

and security of the garrison, while the latter was employed in defending

the fortress and annoying the enemy, that its loss was comparatively

light, and it was chiefly confined to the artillery corps. The marine

brigade, of course, being much more exposed, suffered more severely. In

the course of about nine weeks, the whole number slain amounted to only

sixty-five, and the wounded to three hundred and eighty-eight, and it is a

remarkable fact that the works of the fortress were scarcely damaged.

George the Third

sent General Elliot the order of the Bath, which was presented to him on

the spot where he had most exposed himself to the fire of the enemy. He

also received the thanks of both houses of parliament for his eminent

services, with a pension of fifteen hundred pounds per annum. Elliot

himself, with the consent of the king, ordered medals to be struck, one of

which was presented to every soldier engaged in the defence.

After the

conclusion of peace General Elliot returned to England, and, June 14,

1787, was created Lord Heathfield, Baron Gibraltar. In 1790 he was obliged

to visit the baths of Aix-la-Chapelle for his health, and, when preparing

to proceed to Gibraltar, died at Kalkofen, his favourite residence near

the former place, of a second stroke of palsy, on the 6th of

July of that year. His remains were brought to England, and interred at

Heathfield in Sussex. A monument was erected to his memory in Westminster

abbey at the public expense, and the king himself prepared the plan of a

monument erected in honour of him at Gibraltar. In the council chamber of

Guildhall, London, is one of the most celebrated picturers by Mr. John

Singleton Copley, father of Lord Lyndhurst, representing the siege and

relief of Gibraltar, and full of portraits, in which the figure of its

heroic defender occupies the most conspicuous place, painted at the

expense of the corporation.

[picture of

George Augustus Eliott, Lord Heathfield]

Lord Heathfield was one of the most abstemious men of his age. His diet

consisted always of vegetables and water, and he allowed himself only four

hours’ sleep at a time. He married Anne, daughter of Sir Francis Drake, of

Devonshire, by whom he had a son, Francis Augustus, who succeeded to the

title, which became extinct on his death in 1803.

ELLIOT,

JANE,

authoress of one of the three exquisite lyrics known in Scottish song by

the name of ‘The Flowers of the Forest,’ was the second daughter of Sir

Gilbert Elliot, the second baronet of Minto, and the sister of the third

Sir Gilbert, author of the fine pastoral song of “My sheep I neglected,”

and was born about 1727. Her beautiful song of ‘The Flowers of the Forest’

is the one beginning, with the fragment of the old words,

“I’ve heard them lilting, at the ewe-milking.”

And she

thus proceeds,

“Lasses a’lilting before dawn of day;

But now they are moaning on ilka green loaning;

The Flowers of the Forest are a’ wede awae.”

It is

the only thing she ever produced, and is said to have been written about

the year 1755. When first published, it passed as an old ballad, and long

remained anonymous. Burns was among the first to consider it modern. “This

fine ballad,” he said, “is even a more palpable imitation than Hardy-knute.

The manners are indeed old, but the language is of yesterday.” Sir

Walter Scott inserted it in the Border Minstrelsy in 1803, “as by a lady

of family in Roxburghshire.” It is stated that she composed it in a

carriage with her brother, Sir Gilbert, after a conversation about the

battle of Flodden, and a bet that she could not make a ballad on the

subject. She had high aristocratic notions, and as a proof of her presence

of mind, it is recorded that during the rebellion of 1745, when her father

was forced to conceal himself among Minto Crags, from an enraged party of

Jacobites, she received and entertained the officers at Minto House, and

by her extreme composure, averted the danger to which he was exposed. This

accomplished lady was never married. From 1782 to 1804, she resided in

Brown’s Square, Edinburgh, in a house which, in the progress of local

improvement, is now taken down. She died at Mount Teviot, in

Roxburghshire, the seat of her brother, Admiral Elliot, March 29, 1805.

ELLIOT,

SIR JOHN,

baronet, an eminent physician, was born at Peebles, some time in the first

half of the eighteenth century. He was of obscure parentage, but descended

of a junior branch of the Stobs family, and received a good education,

having become well acquainted with Latin and Greek. He was first employed

in the shop of an apothecary in the Haymarket, London, which he quitted to

go to sea as surgeon of a privateer. Being fortunate in obtaining

prize-money, he procured a diploma, and settled in the metropolis as a

physician. Aided by the friendship and patronage of Sir William Duncan,

uncle of the celebrated admiral, Adam, Viscount Duncan, he soon became one

of the most popular medical practitioners in London; his fees amounted to

little less than five thousand pounds a-year; and by the influence of Lord

Sackville and Madame Schwellenberg, he was, in July 1778, created a

baronet. He was appointed physician to the prince of Wales, became

intimate with persons of rank, and was the associate of the first literary

characters of the metropolis, among whom he was celebrated for his

hospitality. He died November 7th, 1786, at Brocket Hall,

Hertfordshire, from the rupture of one of the larger vessels, and was

buried at Hatfield. Dying unmarried, the baronetcy became extinct at his

death. He was the author of various popular works relative to medical

science, of which a list follows:

Philosophical Observations on the Senses of Vision and Hearing. To which

is added, A Treatise on Harmonic Sounds, and an Essay on Combustion and

Animal Heat. Lond. 1780, 8vo.

Essays on Physiological subjects. Lond. 1780, 8vo.

Address to the Public on a subject of the utmost importance to Health.

Lond. 1780, 8vo. Against Empirics.

An

Account of the Nature and Medicinal Virtues of the principal Mineral

Waters in Great Britain and Ireland, and those in most repute on the

Continent, &c. Lond. 1781, 8vo.

The Medical Picket Book. Lond. 1781, 12mo.

A

Complete Collection of the Medical and Philosophical Works of John

Fothergill, M.D.; with an Account of his Life, and occasional Notes. Lond.

1781, 8vo.

Elements of the Branches of Natural Philosophy connected with Medicine;

including the doctrine of the Atmosphere, Fire, Phlogiston, Water, &c.

Lond. 1782, 8vo, 2d edition, with an Appendix.

Experiments and observations on Light and Colours. To which is prefixed,

the Analogy between Heat and Motion. Lond. 1787, 8vo.

Observations on the Affinities of Substances in Spirit of Wine. Phil.

Trans. Abr. xvi. 79. 1786. |