CONSTABLE,

a surname derived from the ancient high and honourable office of

comes stabuli, count of the stable. Under the French kings the

person who held this office was the first dignitary of the crown, the

commander-in-chief of the armies, and the highest judge in military

affairs. In England there was at one time a lord high constable of the

kingdom, an officer of the crown of the highest dignity. The earl of

Errol is hereditary grand constable of Scotland. Constable was the

family name of the viscounts of Dunbar, a title dormant since 1721.

See DUNBAR, Viscount.

CONSTABLE,

ARCHIBALD,

one of the most enterprising publishers that Scotland has produced,

was born February 24, 1775, at Kellie, parish of Carnbee, county of

Fife. He was the son of Thomas Constable, overseer or land-steward on

the estate of the earl of Kellie. He received all the education he

ever got at the school of Carnbee. In 1788, he was apprenticed to Mr.

Peter Hill, bookseller in Edinburgh, the friend and correspondent of

Burns. While he remained with Mr. Hill, he assiduously devoted himself

to acquiring a knowledge of old and scarce books, and particularly of

the early and rare productions of the Scottish press. On the

expiration of his apprenticeship he married the daughter of Mr. David

Willison, a respectable printer in Edinburgh, who assisted him shortly

after his commencing business, which he did in 1795, in a small shop

on the north side of the High street of that city.

Mr.

Constable’s obliging manners, professional intelligence, personal

activity, and prompt attention to the wishes of his visitors,

recommended him to all who came in contact with him. Amongst the first

of his publications of any importance were Campbell’s ‘History of

Scottish Poetry,’ Dalyell’s ‘Fragments of Scottish History,’ and

Leyden’s edition of the ‘Complaint of Scotland.’ In 1800 he commenced

a quarterly work, entitled the ‘Farmer’s Magazine’ which, under the

management of Mr. Robert Brown of Markle, obtained a considerable

circulation among agriculturists. In 1801 he became proprietor of the

Scots Magazine, a curious repository of the history, antiquities, and

traditions of Scotland, begun in 1739.

Mr.

Constable’s reputation as a publisher may be said to have commenced

with the appearance, in October 1802, of the first number of the

Edinburgh Review. His conduct towards the conductors and contributors

of that celebrated Quarterly was at once discreet and liberal; and to

his business tact and straightforward deportment, next to the genius

and talent of its projectors, may be attributed much of its subsequent

success. In 1804 he admitted as a partner Mr. Alexander Gibson Hunter

of Blackness, after which the business was carried on under the firm

of Archibald Constable and Co. In December 1808 he and his partner

joined with Mr. Charles Hunter and Mr. John Park in commencing a

general bookselling business in London, under the name of Constable,

Hunter, Park and Hunter; but this undertaking not succeeding, it was

relinquished in 1811. On the retirement of Mr. A.G. Hunter from the

Edinburgh firm in the early part of the latter year, Mr. Robert

Cathcart of Drum, writer to the signet, and Mr. Robert Cadell, then in

Mr. Constable’s shop, were admitted partners. Mr. Cathcart having died

in November 1812, Mr. Cadell remained his sole partner. In 1805 he

commenced the ‘Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal,’ a work

projected in concert with the late Dr. Andrew Duncan. In the same

year, in conjunction with Longman and Co. of London, he published the

‘Lay of the Last Minstrel,’ the first of that long series of original

and romantic publications, in poetry and prose, which has immortalized

the name of Walter Scott. In 1806 Mr. Constable brought out, in five

volumes, a beautiful edition of the works of Mr. Scott, comprising the

Lay of the Last Minstrel, the Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, Sir

Tristrem, and a series of lyrical pieces. In 1807 he purchased the

copyright of Marmion, before a line of it was written, from Mr. Scott,

for £1,000. Before it was published, he admitted Mr. Miller of

Albemarle Street, and Mr. Murray, then of Fleet Street, to a share in

the copyright, each of these gentlemen having purchased a fourth.

Amongst

other works of importance published by him may be mentioned here Mr.

J.P. Wood’s edition of Douglas’ Scottish Peerage, Mr. George Chalmers’

Calendonia, and the Edinburgh Gazetteer in 6 vols. In 1808 a serious

disagreement took place between Mr. Scott and Constable and Co.,

owing, it is understood, to some intemperate expression of Mr.

Constable’s partner, Mr. Hunter, which was not removed till 1813. In

1812 Mr. Constable purchased the copyright and stock of the

‘Encyclopaedia Britannica.’ When he became the proprietor, the fifth

edition was too far advanced at press to admit of any material

improvements being introduced into it; but as he saw that these were

largely required, he originated the plan of the Supplement to the

later editions, which has enhanced to such an extent the value, the

usefulness, and the celebrity of the work. In 1814 he brought out the

first of the ‘Waverley Novels;’ and as that wonderful series of

romantic tales proceeded, he had not unfrequently the merit of

suggesting subjects to their distinguished author, and of finding

titles for more than one of these memorable works; such, for example,

was the case with ‘Rob Roy.’ In the same year he published Mr. Scott’s

edition of ‘Swift’s Works.’ Besides these publications, he brought out

the Philosophical Works of Mr. Dugald Stewart. He himself added

something to the stock of Scottish historical literature. In 1810 he

published, from an original manuscript, a quarto volume, edited by

himself, entitled the ‘Chronicle of Fife, being the Diary of John

Lamont of Newton, from 1649 fo 1672;’ and, in 1822, he wrote and

published a ‘Memoir of George Heriot, Jeweller to King James,

containing an Account of the Hospital founded by him at Edinburgh,’

suggested by the introduction of Heriot into the ‘Fortunes of Nigel,’

which was published during the spring of that year. He also published

a compilation of the ‘Poetry contained in the Waverley Novels.’ His

first wife having died in 1814, Mr. Constable married, in 1818, Miss

Charlotte Neale, who survived him.

In the

autumn of 1821, in consequence of bad health, he had gone to reside in

the neighbourhood of London, and his absence from Edinburgh and its

cause are feelingly alluded to in the introductory epistle to the

‘Fortunes of Nigel,’ where Mr. Constable is commended as one “whose

vigorous intellect and liberal ideas had not only rendered his native

country the mart of her own literature, but established there a court

of letters, which commanded respect even from those most inclined to

dissent from many of its canons.” Indeed, his readiness in

appreciating literary merit, his liberality in rewarding it, and the

sagacity he displayed in placing it in the most favourable manner

before the public, were universally acknowledged.

In the

summer of 1822 Mr. Constable returned to Edinburgh, and in 1823 he

removed his establishment to more splendid and commodious premises in

Prince’s Street, which he had acquired by purchase from the

connections of his second marriage. In that year he was included by

the government in a list of justices of the peace for the city of

Edinburgh.

In January

1826 the public was astonished by the announcement of the bankruptcy

of his house, when his liabilities were understood to exceed £250,000.

The year

1825 was rendered remarkable in Great Britain by an unusual rage for

speculation, and the employment of capital in various schemes and

projects, under the name of joint-stock companies.

At this

period the House of which the late Mr. Constable was the leading

partner, was engaged extensively in various literary undertakings, on

some of which large profits had already been realized, while the money

embarked in others, though so far successful, was still to be

redeemed. Messrs. Hurst, Robinson, and Col, the London agents of

Constable’s house, who were also large wholesale purchasers of the

various publications which issued from the latter, had previously to

this period acquired a great addition of capital and stability, as

well as experience in the publishing department, by the accession of

Mr. Thomas Hurst, formerly of the house of Messrs. Longman, Hurst,

Rees, Orme, and Brown, as a partner. But the altogether unprecedented

state of the times, the general demolition of credit, and the utter

absence of all mercantile confidence, brought Messrs, Hurst, Robinson,

and Co. to a pause, and rendered it necessary to suspend payment of

their engagements early in January 1826.

Their

insolvency necessarily led to that of Messrs. Constable and Co., who,

without having been engaged in any speculations extraneous to their

own business, were thus involved in the commercial distress which

everywhere surrounded them.

The liberal

character of the late Mr. Constable in his dealings with literary men,

as well as with his brethren in trade, is well known. His extensive

undertakings, during the period in which he was engaged in business,

tended much to raise the price of literary labour, not merely in

Scotland, but throughout Great Britain. “To Archibald Constable,” says

Lord Cockburn, “the literature of Scotland has been more indebted than

to any other publisher. Ten, even twenty guineas a sheet for a review,

£2,000 or £3,000 for a single poem, and £1,000 each for two

philosophical dissertations (by Stewart and Playfair), made Edinburgh

a literary mart, famous with strangers, and the pride of its own

citizens.” In the department of commercial enterprise, to which he was

particularly devoted, and which, perhaps, no man more thoroughly

understood, his life had been one uniform career of unceasing and

meritorious exertion. In its progress and general results, (however

melancholy the conclusion,) we believe it will be found, that it

proved more beneficial to those who were connected with him in his

literary undertakings, or to those among whom he lived, than

productive of advantage to himself or to his family. In the course of

his business, also, he had some considerable drawbacks to content

with. His partner, the late Mr. Hunter of Blackness, on succeeding to

his paternal estate, retired from business, and the amount of his

share of the profits of the concern, subsequently paid over to his

representatives, had been calculated on a liberal and perhaps

over-sanguine estimate. The reliving the Messrs. Ballantyne of their

heavy stock, in order to assist Sir Walter Scott in the difficulties

of 1813, must also have been felt as a considerable drag on the

profits of the business. In the important consideration as to how far

Messrs. Constable and Co. ought to have gone in reference to their

pecuniary engagements with Messrs. Ballantyne, there are some

essential considerations to be kept in view. Sir Walter’s power of

imagination, great rapidity of composition, the altogether

unparalleled success of his writings as a favourite with the public,

and his confidence in his own powers, were elements which exceeded the

ordinary limits of calculation or control in such matters, and appear

to have drawn his publishers farther into these engagements (certainly

more rapidly) than they ought to have gone. Yet, with these and other

disadvantages, great profits were undoubtedly realized, and had not

such an extraordinary crisis as that of 1825-6 occurred, the concern,

in a few years, would have been better prepared to encounter such a

state of money matters as then prevailed in every department of trade.

The disastrous circumstances of the time, and the overbearing demands

of others, for the means of meeting and sustaining an extravagant

system of expenditure, contributed to drag the concern to its ruin,

rather than the impetuous and speculative genius of its leading

partner.

Mr.

Constable was naturally benevolent, generous, and sanguine. At a

glance, he could see from the beginning to the end of a literary

project, more clearly than he could always impart his own views to

others; but his deliberate and matured opinion upon such subjects,

among those who knew him, was sufficient to justify the feasibility or

ultimate success of any undertaking which he approved. In the latter

part of his career, his situation as the most prominent individual in

Scotland in the publishing world, as well as his extensive connection

with literary men in both ends of the island, together with an

increasing family, led him into greater expense than was consistent

with his own moderate habits, but not greater than that scale of

living, to which he had raised himself, entitled him, and in some

measure compelled him to maintain. It is also certain that he did not

scrupulously weigh his purse, when sympathy with the necessities or

misfortunes of others called upon him to open it. In his own case, the

fruits of a life of activity, industry, and exertion, were sacrificed

in the prevailing wreck of commercial credit which overtook him in the

midst of his literary undertakings, by which he was one of the most

remarkable sufferers, and, according to received notions of worldly

wisdom, little deserved to be the victim.

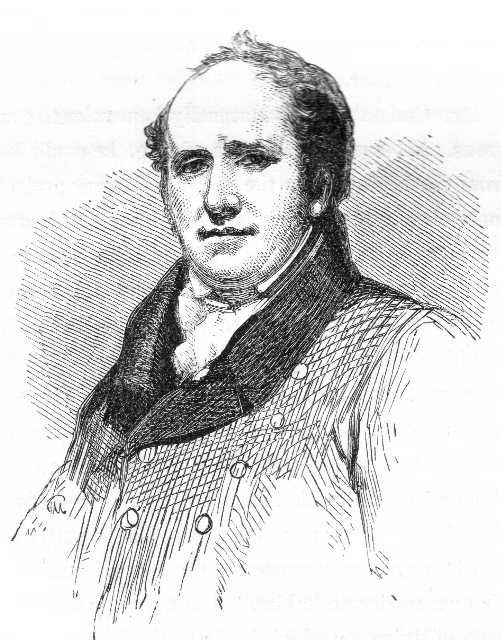

[portrait

of Archibald Constable]

At the time of his bankruptcy took place, Mr. Constable was

meditating a series of publications, which afterwards appeared under

the title of ‘Constable’s Miscellany of Original and Selected Works,

in Literature, Art, and Science,’ – the precursor of that now almost

universal system of cheap publishing, which renders the present an era

of compilation and reprint, rather than of original production. The

Miscellany was his last project. Soon after its commencement he was

attacked with his former disease, a dropsical complaint; and he died,

July 21, 1827, in the fifty-third year of his age. He left several

children by both his marriages. His frame was bulky and corpulent, and

his countenance was remarkably pleasing and intelligent. The portrait

printed by the late Sir Henry Raeburn is a most successful likeness of

him. The preceding woodcut is taken from it. His manners were friendly

and conciliating, although he was subject to occasional bursts of

anger. He is understood to have left memorials of the great literary

and scientific men of his day.