BUCHAN,

anciently BOQUHAN or BUCQUHANE, a surname originally derived from the

district of Buchan, formerly a county of itself, which comprises the

north-eastern part of Aberdeenshire, with part of Banffshire. The name,

like that of Bouchaine in France, Buchianice in Naples, and some others,

seems to have had its origin from Bon or Boi, an old French word now only

found in the Spanish and Portuguese, primarily from the Latin word bos,

an ox, and in reference to the flesh of oxen or cattle, although the

district is now more famed for its corn than its cattle. It is probable

that the names of many similar places in England, as Bukenham or

Buckingham, &c., had the same origin. In another form we have it in

Buccaneers, a Spanish word indicating the kind of food (Bucan,

dried ox flesh) on which these freebooters of the new world almost

exclusively sustained themselves.

_____

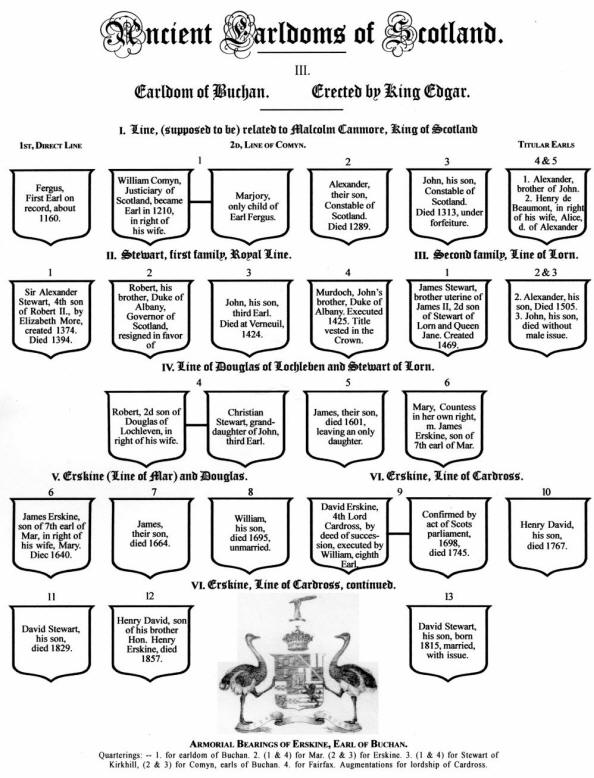

The earldom of

BUCHAN, in the Scottish peerage, at present enjoyed by the Erskine family,

but formerly possessed by the Comyns, is one of the most ancient in

Scotland.

The first earl

of Buchan on record was Fergus, who flourished abut the time of William

the Lion. He is supposed to have been one of the seven earls of Scotland,

who, being displeased at Malcolm the Fourth’s serving under Henry the

Second of England at Toulouse, were disposed to seize his person and eject

him from the throne in the assembly at Perth in 1160. He had no family

name, but as Skene affirms that all the earldoms of Scotland were given by

King Edgar to members of the royal family at that time, it is probable he

was related to the line of Malcolm Canmore. He is mentioned as having made

a grant of a mark of silver annually to the abbacy of Aberbrothwick,

founded by King William.

His only child

Marjory or Margaret, countess of Buchan in her own right, took for her

second husband, in 1210, William Comyn, sheriff of Forfar and justiciary

of Scotland, who became earl of Buchan in right of his wife. He was the

third of the Comyns in Scotland, and had been previously married to a lady

whose name is not known, and by whom he had two sons, of whom Walter, the

second son, was earl of Menteith (which title see). By his second wife,

the countess of Buchan, he had three sons and a daughter, Elizabeth,

married to William earl of Mar. He died in 1233, and was survived by his

countess.

Their son,

Alexander Comyn, second earl of Buchan of this name, acted a prominent

part in the busy reigns of Alexander the Second and Third. In 1244 he was

one of the guarantees of the peace with England, and in 1251 was appointed

justiciary of Scotland, but being one of the Scottish party who were

obnoxious to King Henry the Third, he was removed from that high office

four years afterwards. In 1257, however, he was restored to it, and held

it till his death. He married Elizabeth, second daughter of Roger de

Quinci, earl of Winchester and constable of Scotland, on whose death, in

1264, without male issue, the earl of Buchan obtained, in right of his

wife, a full share of her father’s estates in Galloway and in other

counties; and on the resignation of the office of constable by Margaret

countess of Derby, the elder sister of his wife, in 1270, he became, in

right of the latter, constable of Scotland. He was one of the magnates

Scotiae, who, on 5th February 1284, engaged to maintain the

succession of the princess Margaret of Norway to the crown, on the death

of her grandfather, being the first of thirteen earls present at the

parliament held at Scone on that day. In 1286, on the death of Alexander

the Third, he was chosen one of the six guardians of Scotland. He died in

1289, and was succeeded by his son John, also constable of Scotland.

John, third earl

of Buchan of the Comyn family, adhered to the English interest, and with a

tumultuous band of followers he encountered King Robert the Bruce, 25th

December 1307, but his troops fled at the first onset of Bruce’s army. In

the following year he assembled a numerous force, but was defeated by

Bruce, with great slaughter, at Inverury, 22d May 1308. Soon afterwards he

retired to England, where he died before 28th April 1313. His

wife, Isabel, the daughter of Duncan, earl of Fife, was the high-spirited

lady who placed the crow n on the head of Robert the Bruce, as referred to

in that article.

John’s brother

Alexander was styled fourth earl of Buchan, and Henry de Beaumont, an

Englishman who married Alexander’s eldest daughter, Alice, assumed the

title of fifth earl of Buchan, in right of his wife. He died in 1341.

In 1371 a grant

of this earldom was obtained from Robert the Second by Sir Alexander

Stewart, knight, his fourth son by his first wife, Elizabeth More, long

known, from his savageness, by the name of the Wolf of Badenoch. He had

also the earldom of Ross for life, in right of his wife, Euphame, countess

of Ross, by whom he had no issue, but he left five natural sons,

Alexander, earl of Mar, Sir Andrew, Walter, James and Duncan, from whom

several families of the name of Stewart are descended. Having seized the

bishop of Moray’s lands he was excommunicated, and in revenge he, in May

and June 1390, burnt the towns of Ferres and Elgin, with the church of St.

Giles, the maison dieu, and the cathedral, and eighteen houses of the

Canons, for which he did penance in the Blackfriar’s church of Perth,

before the altar, and was obliged to make full satisfaction to the bishop.

He died 24th July 1394.

At his death it

devolved on his brother Robert, duke of Albany, when it was granted to

John Stewart, his eldest son, born in 1380, to whom his father gave the

barony of Coul and O’Niel in Aberdeenshire, and who, for his valour, was

surnamed “the brave John o’Coul.” In 1416, he was sent to England to

complete the treaty for the release of James the First, in which he was

unsuccessful. In 1420, he went to France, at the head of seven thousand

Scotch auxiliaries, to support the right of Charles the Seventh to the

French crown against the English. At the battle of Beauge in Anjou, 22d

March 1421, he defeated the English under the duke of Clarence. He was

slain at the battle of Verneuil in Normandy, 17th August 1424.

By his wife Lady Elizabeth Douglas, second daughter of Archibald, fourth

earl of Douglas and duke of Touraine, he left an only daughter, Margaret,

married to George, second Lord Seton, and from them were descended, in a

right line, all the lords of the now extinct house of Seton, earls of

Winton (see WINTON, earl of].

The earldom of

Ross which his father had procured for him fell to the crown on his death,

but the earldom of Buchan devolved on his brother Murdoch, duke of Albany,

at whose execution in 1425, it was forfeited.

In 1466, it was

bestowed on James Stewart, surnamed “Hearty James,” uterine brother of

King James the Second. He was the second son of Sir James Stewart, the

black knight of Lorn, by Jane, queen of Scotland, the widow of James the

First. In 1471, on the fall of Lord Boyd, he was constituted high

chamberlain of Scotland, and in 1473, he was sent ambassador to France,

when he obtained a safe conduct for passing through England. He died

before 1500.

His son and

grandson both succeeded as earls of Buchan.

John, master of

Buchan, eldest son of the latter, had, by his second wife, Margaret,

daughter of Walter Ogilvie of Boyne, a daughter, Christian Stewart, who

succeeded to the title, and by her marriage in 1469 with Robert Douglas,

second son of Sir Robert Douglas of Lochleven, uterine brother of the

regent Moray, he became earl of Buchan, in right of his wife.

They had two

daughters, and a son, James, who became fifth earl of Buchan of this

family. He died 26th August, 1601, aged 21. By his wife,

Margaret, second daughter of Walter, first Lord Ogilvy of Deskford, he had

an only child, Mary Douglas, countess of Buchan, in her own right, by

whose marriage with James Erskine, son of John, seventh earl of Mar, lord

high treasurer of Scotland, and first Lord Cardross [see CARDROSS, lord,]

this earldom passed into the Mar branch of the Erskine family. Of this

first earl of Buchan of the house of Erskine, there is a portrait in

Smith’s Iconographia Scotica, of which the following is a cut:

portrait of

James Erskine earl of Buchan

James Erskine, sixth earl of Buchan, was one of the lords of the

bedchamber to King Charles the first, and resided much in England. He died

in 1640. His eldest son James, seventh earl, married Lady Marjory Ramsay,

eldest daughter of the first earl of Dalhousie, by whom he had four

daughters and one son, William, who succeeded in October 1664 as eighth

earl of Buchan. At the revolution he adhered to the party of King James,

but falling into the hands of King William’s forces, he was committed

prisoner to the castle of Stirling, where he died in 1695, unmarried. At

his death, the succession to the earldom opened to David, fourth lord

Cardross, eldest son of Henry the third lord; and in the parliament of

1698 an act was passed allowing him to be called in the rolls of

parliament as earl of Buchan.

Henry David, the tenth earl, married Agnes, daughter of Sir James Steuart

of Coltness, baronet, and granddaughter of Sir James Steuart, lord

advocate to King William and Queen Anne, popularly called Jamie Sylie; and

by him had with a daughter and a son David, who died young, David Steuart

Erskine, the eleventh earl, and his two celebrated brothers, the Hon.

Henry Erskine, father of the 12th earl, and Thomas, created

Lord Erskine, lord chancellor; notices of whom are subsequently given in

their place, under the head of ERSKINE.

Earl Henry, the father of these three celebrated brothers, was a man of

infinite good nature and polite manners, but ordinary understanding. In

1745, when the young Chevalier arrived in Edinburgh, he had a great desire

to be introduced to him, but not wishing to commit himself by joining the

standard of rebellion, he, along with his brother-in-law, the celebrated

Sir James Steuart of Coltness, requested their friend Lord Elcho, who was

Sir James’s brother-in-law, and one of the prince’s firmest adherents, to

take them, as it were, upon compulsion, to the court at Holyroodhouse.

Next day, therefore, according to concert, they were seized at the cross

of Edinburgh by a party under the command of Elcho, and straightway

brought into an ante-chamber of the palace. The prince, however, on the

matter being explained to him, refused to see them, unless as avowed

adherents. Sir James Steuart consented, was introduced, and ruined, while

the earl of Buchan, with a low and sarcastic obeisance to Lord Elcho,

turned upon his heel, and left the palace. He thus saved his estates from

confiscation, but unfortunately, it was only to squander much of their

value in another way. At his death in 1767 he left his children little

better inheritance than their talents, for which they were more indebted

to their mother than to him.

Henry David Erskine, twelfth earl of Buchan of the name, son of the

celebrated Hon. Henry Erskine, by his wife, the daughter of George

Fullerton, Esq. of Broughton Hall, died in 1857. Born in 1783, he was

three times married. His eldest son Henry, Lord Cardross, died in 1837,

leaving a son, born in 1834, and died in 1849. His second son, David

Stuart Erskine, born in 1815, succeeded as 13th earl; married,

with issue. Besides that of Lord Cardross, the earl also holds the

secondary title of Lord Auchterhouse, conferred in 1606.

_____

Of

the principal families of this name are the Buchans of Auchmacoy, in the

parish of Logie-Buchan, Aberdeenshire, who have been proprietors of that

estate, as appears from Robertson’s Index of Scarce Charters, since the

year 1318, holding it of the earl of Buchan until the forfeiture of the

Comyns in the reign of King Robert the Bruce. IN 1503, James the Fourth

gave Andrew Buchan of Auchmacoy a new charter, and erected his lands into

a free barony, which has been inherited by his lineal male descendants

ever since. The family of Auchmacoy were remarkable for their steady

loyalty to the Stuarts, and their opposition to the Covenant. Of this

family was the celebrated Major-General Buchan, the last officer who had

the chief command of King James’s forces in Scotland, after the revolution

of 1688. He was the third son of James Buchan of Auchmacoy, by Margaret,

daughter of Alexander Seton of Pitmedden, and was born about the middle of

the seventeenth century. He entered the army young, and after serving in

subordinate ranks in France and Holland, he was in 1682 appointed by

Charles the Second lieutenant-colonel, and in 1686, by James the Seventh,

colonel of the earl of Mar’s regiment of foot in Scotland. He received the

thanks of the privy council for various services, and in 1689 was promoted

by King James to the rank of major-general. After the fall of the Viscount

Dundee at Killiecrankie, and the subsequent repulse of his successor,

Colonel Cannan, at Dunkeld, he was appointed by King James, who was then

in Ireland, commander-in-chief of all the Jacobite forces in Scotland. He

took the field in April 1690, and on his arrival from Ireland a meeting of

the chiefs and principal officers was held at Keppoch, to deliberate on

the course which they ought to pursue, when it was unanimously resolved to

continue the war. As, however, the labours of the spring season were not

over, they postponed the muster of the clans till these should be

completed, and in the meantime directed Major-general Buchan to employ the

interval in beating up the enemy’s quarters, along the borders of the

lowlands, for which purpose a detachment of twelve hundred foot was to be

placed at his disposal. [Balcarres.] It so happened that the

general’s brother, Lieutenant-colonel Buchan, had joined the party of the

government, and at this time commanded King William’s forces in the city

and county of Aberdeen, and he was directed by General Mackay to march

upon any point where he could co-operate with Sir Thomas Livingston, who,

at the head of a large force, was acting as a check upon the movements of

the Jacobite forces in the Southern Highlands. At Cromdale, early in the

morning of the first of May (1690), Livingston surprised and defeated

General Buchan and the forces under his command, then reposing in the low

grounds, on the south banks of the Spey, which gave rise to the well-known

song of ‘The Haughs of Cromdale,’ beginning —

“As I came in by Auchindown,

A little wee bit frae the town,

When to the Highlands I was bown,

To view the haws o’Cromdale;

I met a man in tartan trews,

I speer’d at him what was the news,

Quo’ he, the Highland army rues

That e’er we came to Cromdale.

We were in bed, Sir, every man,

When the English host upon us came;

A bloody battle then begun,

Upon the haws of Cromdale.

The English horse they were so rude.

They bathed their hoofs in Highland blood,

But our brave clans they boldly stood,

Upon the haws of Cromdale.

But, alas! We could no longer stay,

For o’er the hills we came away,

And sore we do lament the day,

And view the haws of Cromdale.”

The

names of Montrose and Cromwell are, in the rest of the song, by an absurd

anachronism, substituted for those of Buchan and Livingstone, while some

of the clans enumerated were not in the skirmish at all. The popular songs

of a country sometimes make sad havoc with fact and even probability, as

history is often “made void through traditions.”

Buchan afterwards, at the head of a considerable force, being joined by

Farquharson of Inverey with about six hundred of Braemar Highlanders, left

the neighbourhood of Abergeldie, where he had been for some time, and

descended into the low parts of Aberdeenshire, Mearns, and Banff, but were

opposed by the master of Forbes and Colonel Jackson, with eight troops of

cavalry. Buchan, however, purposely magnified the appearance of his

forces, by ranging his foot over a large extent of ground, and

interspersing his baggage and baggage horses among them, which inspired

the Master of Forbes and Jackson with such dread that they considered it

prudent to retire before a foe apparently so formidable. They accordingly

retreated to Aberdeen at full gallop, a distance of twenty miles. Buchan,

who had no immediate design upon Alberdeen, followed them, and was joined

in the pursuit by some of the neighbouring noblemen and gentlemen. The

inhabitants were thrown into a state of the greatest consternation at his

approach, and the necessary means of defence were adopted, but Buchan made

no attempt to enter the town, and marched southward. On the advance,

however, of General Mackay, he crossed the hills to the right, and

proceeded to Iverness, where he expected the earl of Seaforth’s and other

Highlanders to join him, when he intended to have attacked the town, but

Seaforth was obliged to surrender to the government, and crossing the

river Ness, Buchan retired up along the north side of the Loch. At length,

unable to collect or keep any considerable body of men together, after

wandering through Lochaber, he dismissed the few who still remained with

him, and along with Sir George Barclay, and other officers, took up his

abode with Macdonell of Glengary. After the submission of the Highland

chiefs to the government of King William, Buchan and Cannan, with their

officers, in terms of an agreement with the ruling powers, were

transported to France, to which country they had asked and obtained

permission from King James to retire, as they could no longer be

serviceable to him in Scotland. Although he had failed to retrieve the

fortunes of the fallen monarch, there are letters to him and other

documents in the possession of Mr. Buchan of Auchmacoy, from James

himself, and his queen, their secretary Melfort and others, expressive of

their undiminished confidence in his military skill and attachment to

their cause. On the breaking out of the rebellion in 1715, the marquis of

Huntly wrote a letter to General Buchan, soliciting him to join the forces

of the earl of Mar, and he is supposed, though not in command, to have

been present with the marquis of Huntly’s troops at the battle of

Sheriffmuir, on the 13th November 1715, but when the marquis,

to save his life and estates, withdrew from the earl of Mar’s army, a few

days after, it is doubtful whether the general followed his example, as by

a letter from the countess of Errol, dated 15th May 1721, it

appears that he was still in communication with the exiled family. His

portrait is in the house of Auchmacoy, Aberdeenshire.

A

family of the name of Buchan possesses the estate of Kelloe in

Berwickshire. The son of George Buchan, Esq. of Kelloe, by the daughter of

Robert Dundas, Esq. of Arniston, viz., Lieutenant-general Sir John Buchan,

who distinguished himself in the Peninsular war, was, for his services,

created a knight commander of the Bath in 1831. Died 1850.

BUCHAN,

WILLIAM, M.D.,

a medical writer of great popularity, was born in 1729, at Ancrum, in

Roxburghshire. His father possessed a small estate, and in addition rented

a farm from the duke of Roxburgh. He was sent to Edinburgh to study

divinity, and spent nine years at the university. At an early period he

exhibited a marked predilection for mathematics, in which he became so

proficient as to be enabled to give private lessons to many of his

fellow-students. He afterwards resolved to follow the medical profession,

in preference to the Church. Before taking his degree, he was induced by a

fellow-student to settle in practice for some time in Yorkshire. He soon

after became physician to the Foundling Hospital at Ackworth, in which

situation he acquired the greater part of that knowledge of the diseases

of children which was afterwards published in his ‘Domestic Medicine,’ and

in his ‘Advice to Mothers.’ He returned to Edinburgh to become a Fellow of

the Royal College of Physicians, and soon after married a lady named

Peter. On the Ackworth Foundling Hospital being dissolved, in consequence

of parliament withdrawing its support from it, Dr. Buchan removed to

Sheffield, where he appears to have remained till 1766. He then commenced

practice in Edinburgh. In 1769 he published his celebrated work, ‘Domestic

Medicine; or, the Family Physician;’ dedicated to Sir John Pringle,

president of the Royal Society. In the composition of it he is said to

have been assisted by Mr. William Smellie. It was published at Edinburgh

at six shillings; and so great was its success, that, in the words of the

author, “the first edition of five thousand copies was entirely sold off

in a corner of Britain, before another could be got ready.” The second

edition appeared in 1772, and before the author’s death nineteen large

editions had been sold. The work was translated into every European

language, and became very popular, not only on the continent, but in

America and the West Indies. From the empress Catherine of Russia the

author received a large medallion of gold, with a complimentary letter.

Many other letters and presents from abroad were also transmitted to him.

Dr. Buchan subsequently removed to London, where for many years he enjoyed

a lucrative practice. In his latter years, he went daily to the Chapter

Coffeehouse, St. Paul’s, where patients resorted to him, to whom he gave

advice. Before leaving Edinburgh he delivered several courses of natural

philosophy, illustrated by an excellent apparatus bequeathed to him by his

deceased friend, James Ferguson, the celebrated lecturer. On his removal

to London, he disposed of this collection to Dr. Lettsom. He died February

25, 1805, and was interred in the cloisters of Westminster Abbey. He left

a son, also an eminent physician and the author of several medical works.

Dr. Buchan’s works are:

Domestic Medicine; or a Treatise on the Prevention and Cure of Diseases,

by regimen and simple medicines. Lond. 1769. 2d edition, with additions.

Lond. 1772, 8vo.

Cautions concerning Cold Bathing and Drinking Mineral Waters; being an

additional chapter to the 9th edition of his Domestic Medicine.

Lond. 1786, 8vo.

Letters to the Patentee concerning the Medical Properties of fleecy

Hosiery; with Notes and Observations. 3d edit. Lond. 1790, 8vo.

Observations on the Prevention and Cure of the Venereal Disease; intended

to guard the ignorant and unwary against the baneful effects of that

insidious malady, &c. Lond. 1796, 8vo. Several editions.

Observations on the Diet of the Common People; recommending a method of

living less expensive, and more conducive to health, than the present.

Long. 1797, 8vo.

Advice to Mothers on the subject of their own Health, and on the means of

promoting the health, strength, and beauty of their offspring. Lond. 1803,

8vo. 2d edit. Lond. 1811, 8vo.

The works of his son, Alexander P. Buchan, M.D., London, are:

Enchiridion Syphiliticum, or Directions for the Conduct of Venereal

Patients. Lond. 1798, 8vo.

Practical Observations concerning Sea Bathing, with Remarks on the use of

the Warm Bath. Lond. 1804, 8vo.

New edition of Armstrong on Diseases of Children, with notes. Lond. 1808,

8vo.

Bionomia, or Opinions concerning Life and Health. Lond. 1811, 8vo.

New edition, being the 21st, of Dr. Buchan’s Domestic Medicine.

Lond. 1813, 8vo.

Account of an appearance off Brighton Cliff, seen in the air by

reflection. Nic. Jour. xiv. 340. 1806.

BUCHAN,

OR SIMPSON, ELSPETH,

the foundress of a sect. partly enthusiastic millenarians, and partly

harmless fanatics, was born in 1738. She was the daughter of John Simpson,

the keeper of an inn, at Fetney-Can, situated half-way between Banff and

Portsoy; and, in her 22d year, she went to Glasgow, and entered into

service. There she married Robert Buchan, a potter, one of her master’s

workmen, in the delft-work, Broomielaw, by whom she had several children.

Although educated an Episcopalian, she adopted, on her marriage, the

principles of her husband, who was a Burgher Seceder. Afterwards, laying

claim to the gift of inspiration, which she supported by asserting that

she had had a vision “in the fields,” when about six or seven years of

age, and that at the age of thirty-four “the power of God wrought so

powerfully upon her senses that she could make no use of food for weeks,”

she began, sometime about the year 1779, to promulgate singular doctrines.

Mr. Hugh White, a minister of the gospel, a licentiate of the Church of

Scotland, and recently admitted into connection with the synod of Relief

at Irvine, being called to Glasgow at the April sacrament of 1783, Mrs.

Buchan heard him preach, and being much taken with his discourse, she

wrote several letters to him, and a correspondence ensured, which

terminated, four months afterwards in her visiting him at Irvine. On her

appearance there she was kindly received, and by her artful conversation

soon converted not only Mr. White but his wife to her own peculiar

notions, and through him a few of his hearers, none of whom, however, were

of the wealthy of his flock. The latter portion of his congregation,

disapproving of their minister’s conduct, brought him before the

presbytery, who after he had disregarded a suspension, and continued to

preach his new doctrines, were compelled to depose him from the office of

the ministry. He afterwards preached and otherwise laboured to propagate

his fanatical tenets, first in a tent, and subsequently in his own house.

His adherents met during the night, sung hymns, which was a great part of

their worship, and the uninitiated were instructed in the new faith by

their pretended prophetess, who signed her name “Elspat Buchan,” and,

though illiterate, had some natural ability. She gave herself out to be

the woman spoken of in the 12th chapter of the Revelation, and

Mr. White to be the man-child she had brought forth. This and some other

of her ravings brought upon her and her party the indignation of the

townspeople. They rose, assembled round Mr. White’s house, broke the

windows, and might have proceeded to greater extremities but for the

interposition of the magistrates. After repeated applications to have her

proceeded against as a blasphemer, the magistrates thought it prudent, in

April 1784, to dismiss her and several of her adherents from the town.

They conducted her safely without the bounds of the borough, but at

parting, she and her companions were pelted by the youthful mob who were

following them, with dirt and stones. The first night they stopped in the

neighbourhood of Kilmaurs, and being joined by Mr. White and a few others

in the morning, the whole proceeded till they came to the parish of

Closeburn, Dumfries-=shire, where they took up their abode for a season.

The farm of New Cample in the parish of Closeburn, in the outhouses or

offices of which they took up their abode, (now called Buchan Ha’,)

continued to be their residence till 24th December of that

year, when, under a popular belief that Mrs. Buchan was a dealer in

witchcraft, they were assailed by a mob of rustics, but were protected by

the sheriff, and forty-two of the rioters tried before him for the breach

of the peace. The persons who came from Irvine were mostly females, but

among them were a few men of respectable character and easy circumstances,

including a Mr. Hunter, a lawyer and fiscal of that town. They were joined

at New Cample by a lieutenant of marines, by name Charles E. Conyers, who

resigned his commission, and by a few from the counties on the English

border, but their number never amounted to more than fifty. Their

proceedings and the few conversions they made caused a sensation, and they

were beset with letters inquiring into their principles and views. They

could number one countess at least among their correspondents, besides

several clergymen of the church of England; and they began vauntingly to

publish their correspondence. They also issued from the press two parts of

a work called ‘The Divine Dictionary,’ containing their notions and

revelations, each accompanied with the following blasphemous attestation:

“The truths contained in this publication, the writer received from the

Spirit of God in that woman, predicted in Rev. xii. 1. though they are not

written in the same simplicity as delivered – by a babe in the love of

God, HUGH WHITE. Revised and approven of by ELSPAT SIMPSON.”

Nothing could be more injurious to their cause than to write such a book.

So little reason was mixed with their madness, that it is difficult

at times in its pages to comprehend their meaning or to correctly grasp at

their belief. It showed them to be illiterate, visionary, and rhapsodical.

Their main doctrine was that a coming of Christ in person, or what is

called the millennium, was just at hand; on which occurring, they

would be taken up to meet h im in the air, transformed into his likeness,

and would reign with him for a thousand years. They believed that none of

them were to taste of death; that the approach of the Saviour would be

hastened by their assuming the position of waiters or expectants, and in

particular by their living like the angels in heaven. They emaciated their

bodies by fasting. They renounced all earthly connections. Such of them as

were in the relation of husband and wife ceased to know each other as

such. They asserted that sin no longer existed in their heart, – that

there was impropriety in praying for the pardon of sin, – that the soul

had no existence separate from the body, – that at conversion a spiritual

life was infused, which consisted in rejoicing in God, singing hymns, and

waiting in ecstacy for the appearing of their Redeemer. Mrs. Buchan was

not only the high priestess but the treasurer of the party. She kept the

common stock of the brethren and sisters, for they had all things in

common. All the funds they brought with them, and they were considerable,

she contrived to get into her hands. She dealt out their food to them –

and that in small portions; she led their hymns; she poured out her

rhapsodies over the Bible; she asserted herself to be not only the women

mentioned in the Apocalypse, but the mother of Christ, who had been

wandering in the world ever since his days, and that she would never die.

Although she had a husband and son left behind in Glasgow, and two

daughters who were of the party and living before her eyes, she asserted,

and got her followers to believe her, that every thing was false about her

parentage, marriage, or motherhood. Notwithstanding these absurd views,

the Buchanites were temperate, civil, and peaceful in a remarkable degree.

The young women particularly excited much commiseration. When the trial of

the rioters came on, they would not prosecute, nor scarcely bear witness

in reference to the injuries they had received, until the one first called

had been imprisoned for suppressing the truth.

After the trial they saw they could only be in safety by having a little

spot of ground they could call their own. Accordingly they removed to the

neighbouring county of Galloway, and possessed a farm called Auchencairn,

near the village called ‘the Nine-mile Tollbar.’ Here they remained until

the death of the prophetess. Various defections, however, took place. The

young women were induced to marry in the neighbourhood, or otherwise

returned into society. The former was even the case with Mrs. Buchan’s

daughters. A few continued, however, until she died in May 1791.

On

her death-bed, this wretched imposter called her followers together, and

endeavoured to cheer their drooping spirits by asserting that though she

new appeared to die, they need not be discouraged, for in a short time she

would return and conduct them to the New Jerusalem. After her death, her

credulous disciples would neither dress her corpse nor bury her, until

compelled by the authorities. The last survivor of the sect, whose name

was Andrew Innes, died in 1848. He had kept the skeleton of Mrs. Buchan

bedside him, always expecting that she would come alive again as she had

foretold, and carry all her followers to heaven. The Buchanites were

remarkably peaceable and industrious, and excelled in the manufacture of

spinning wheels, formerly to be found in every cottage, but now superseded

by the spinning-jennies of the great steam factories. – Struthers’

History of the Relief Church.

The name Buchan in the

Dictionary of National Biography