|

BRUCE,

or as it was anciently written, BRUS, the name of a family of Norman

descent, which became one of the most illustrious in the annals of Scotland.

The name, originally Brusi, had its origin among the Scandinavians or

Northmen, and appears – through their matrimonial alliances with the

vikingrs of Norway, who subdued the Orkney islands – in connection with the

royal family of Scotland at a very early period of its authentic history.

Sigurd the Stout, jarl or earl of Orkney, who married the daughter of

Melkolm, probably Malcolm the Second, king of Scots, had four sons, Thorfinn,

Sumarled, Brusi, and Elinar. Brusi, the third son, the Orkneyinga

Saga, as quoted in the ‘Collectanea de Rebus Albanicis,’ printed for the

Iona Club, informs us, was a very peaceful man, and clever, eloquent, and

had many friends. After the death of Sumarled, disputes arose amongst the

brothers about the division of his lands in Orkney and Caithness, and wars

and scarcity ensued, but Brusi was contented with his third of Orkney, and

“in that part of the land which Brusi had there was peace and prosperity.”

From a branch of

this family came, accordeing to Burke, Robert de Brusi, a descendant of

Einar, fourth jarl of Orkney, brother of the famous Rollo,

(great-great-grandfather of William the Conqueror,) who in 912 acquired

Normandy, and became its first duke. This Robert de Brusi built the castle

of La Brusee, now called Brix, in the diocese of Coutanse, near Volagnes. By

his wife, Emma, daughter of Alain, count of Brittany, he had two sons, Alain

de la Brusee, lord of Brusee castle, (married Agnes, daughter of Simon

Montfort, earl of Evreux,) whose posterity remained in Normandy, and Robert

de Brusee, the ancestor of the Bruses, and the first of that name who

appeared in England. He accompanied William the Conqueror there in 1066, but

died soon after. By his wife, Agnes, daughter of Waldonius, count of St.

Clair, he had two sons, William and Adam, who both attended their father

into England, and acquired great possessions, the former in Sussex, Surrey,

Dorsetshire, and other counties, and the latter in Cleveland, of which the

barony of Skelton was the principal. Adam died in 1098, leaving, by Emma his

wife, daughter of a knight named Sir William Ramsay, three sons, namely, Sir

Robert his heir; William, prior of Guisburn, and Duncan. After the death of

his father, Sir Robert had forty-three lordships in the East and West

Ridings of that county, and fifty-one in the North Riding, whereof Guisburn

in Cleveland was one [Dugdale’s Baronage, v. i. p. 447.]

His son, Robert de

Brus of Cleveland, served as a companion in arms under Prince David,

afterwards David the First of Scotland, during his “residence,” says our

authority, “at the court of Henry the First of England;” but in reality, and

as in all probability and consistency, during the conquest and a part of the

period of his government of Cumbria – the district comprising the Lothians

and Galloway as bestowed on that prince upon the death of his brother Edgar,

– and received from him, along with the hand of a lady, a native of the land

and heiress thereof, as his second wife, a grant of the lordship of

Annandale, comprising all that territory called in Norman French

Estra-hanent, ‘beyond or across Annent or Amnant,’ (afterwards altered

into Strathannan or Annandale,) and all the lands from Estra-nit (Strathnith)

the bounds of the property of Dunegall, (ancestor of the Randolphs, earls of

Moray) into the limits of Ranulph de Meschines, then lord of cumberland,

with a right to enjoy his casdtle there, with all the customs appertaining

to it. The charter by which this large domain was conferred upon him

established the tenure by the sword; that is, gave a right to take

possession and retain by force of arms. For this princely gift, which he

held by the tenure of military service, he did homage to the Scottish king.

In 1138, during the civil war between King Stephen who had usurped the

throne of England, and Matilda, the rightful heiress, niece of the king of

Scots, when the latter, in support of the claims of his relative, had led an

expedition into England and advanced as far as Northallerton, de Brus was

sent, by the barons of the north of England, (who, if not attached to the

cause of Stephen, were satisfied it was their safety to maintain it and had

assembled a force for that purpose,) in order to gain time to increase their

strength, to negotiate, or rather to remonstrate with him. At the

commencement of the war, he had renounced his allegiance to David, and

resigned his lands in Annandale to his son by his second marriage. He

represented that the English and Normans, against whom he was then arrayed,

had repeatedly restored the power and authority of the Scottish monarchs

when driven out by their subjects of the ancient races of the country, and

that they were more faithful to the royal family than were the Scots

themselves, who rejoiced at this unnatural war, because it afforded them an

opportunity of displaying their resentment against those who had often

frustrated their treasonable devices. He dwelt on the savage outrages which

that portion of the army, consisting of native forces, had committed, urged

him to prove the truth of his disavowal of them by withdrawal, assured him

of the determined resistance of the Yorkshire barons, and concluded (as

reported by their common friend Aldred) in the following affectionate

strain: – “It wrings my heart,” said he, “to see my dearest master, my

patron, my benefactor, my friend, my companion in arms, in whose service I

am grown old, thus exposed to the danger of battle, or to the dishonour of

flight,” and then he burst into tears. David also wept, but his resolution

to maintain the rights of his sister’s daughter, to whom as her first

subject he had sworn fealty, continued unchanged. The battle of the Standard

followed, 11th August, 1138, in which the army of King David,

after a partial succession the first onset, was completely defeated. At this

famous battle de Brus took prisoner his second son, Robert, a youth of

fourteen years of age, who, being liegeman to the Scottish king for the

lands of Annandale, which had been renounced in his favour by his father,

had fought on the Scots side. Robert de Brus, first lord of Annandale,

founded a monastery at Guisburn, now Guisborough, in Yorkshire, in 1119, and

amply endowed it with lands and possessions, in which he was joined by

Agnes, his first wife, daughter of Fulk Paynell, with whom he got the manor

of Carleton in Yorkshire, and Adam his son and heir. His death took place 11th

May 1141, when his English estates were inherited by his eldest son Adam,

whose male line terminated in Peter de Brus of Skelton, constable of

Scarborough castle, who died 18th September 1271, leaving his

extensive estates to four sisters, his co-heiresses, all married to powerful

English barons.

Robert de Brus,

his son by the second marriage, inherited Annandale in right of his mother

and by cession of his father, was by him, after the battle of the Standard,

sent prisoner to King Stephen, who ordered him to be delivered up to his

mother. On telling his father that the people of Annandale had no wheaten

bread, he conferred on him the lordship of Hert and the territory of

Hertness in the bishopric of Durham, to hold of him and his heirs, lords of

Skelton. He soon, however, returned to Scotland, and gave to the monastery

of Guisburn, founded by his father, the churches of Annand, Lochmabel,

Kirkpatrick, Cummertrees, Rampatrick, and Gretenhou (or Graitney, now

Gretna), and entered into a composition with the bishop of Glasgow,

concerning these churches, to which that prelate laid claim. “To show that

he looked upon his chief settlement to be in Scotland he quitted his

father’s armorial bearings (argent, a lion rampant, gules) and assumed the

coat of Annandale (or a saltire and chief gules.)” King William the Lion

conferred on him by a charter yet extant, dated at Lochmabel, the grant of

Annandale made to his father by David the First. He and his wife Euphemia

gave to the monks of Holmeultram the fishing of Torduff in the Solway Firth.

He had two sons, Robert and William.

Robert, the elder

son and third lord of Annandale, described as “a nobleman of great valour

and magnanimity, and at the same time pious and religious,” married, in

1183, Isabella, a natural daughter of William the Lion, by whom he had no

issue. He died before 1191. His widow married, a second time, a baron named

Robert de Ros.

The second son

William had a son named Robert, fourth lord of Annandale, surnamed the

noble, who took to wife Isobel, second daughter of David, earl of Huntingdon

and Chester, younger brother of William the Lion, and thus laid the

foundation of the royal house of Bruce. “By this royal match the lords of

Annandale came to be amongst the greatest subjects in Europe; for, by the

said Isobel (as coheiress, with her two sisters, of her father’s property,)

Robert, exclusive of his paternal estate in both kingdoms, came to be

possessed of the manor of Writtle and Hatfield in Essex, together with half

the hundred of Hatfield. She likewise brought him the castle of Kildrummie

and the lordship of Garioch in Aberdeenshire, and the manor of Connington in

Huntingdonshire, and Exton in Rutlandshire.” He died in 1245, and was buried

with his ancestors in the abbey of Guisburn, in Cleveland.

His eldest son,

also named Robert, was the competitor with John Baliol for the crown of

Scotland. He died in 1295.

Robert de Brus,

his eldest son, sixth lord of Annandale, and first earl of Carrick of the

name, [see ANNANDALE, lord of, and CARRICK, earl of], maintained his

pretensions to the Scottish throne. Nevertheless, he accompanied Edward the

First into Scotland, and fought on the English side at the battle of Dunbar.

He died in 1304.

His eldest son,

Robert de Brus, (as it was written and used by all parties in that Norman

French which was the spoken language of Scotland during his lifetime, but in

after ages not very accurately translated into English as The Bruce,) the

conqueror at Bannockburn, and the restorer of the Scottish monarchy, was the

seventh lord of Annandale, and second earl of Carrick in right of his

mother.

In the genealogy

of the royal line of Brus, it appears that there had been nine persons in

direct descent from de Brus of Doomesday Book to de Brus of Bannockburn, the

first king of the name, inclusive, eight of whom were named Robert, and one

William, the latter being the grandson of the Norman knight Robert de Burs,

and younger brother of the third Robert.

Of the lives of

the three last of these Bruces as more particularly connected with the

history of Scotland, the details are more fully given in their order, as

also that of Edward, one of the brothers of King Robert; viz.: –

BRUCE, or DE BRUS,

ROBERT, fifth

lord of Annandale, is known in history as Bruce the Competitor, to

distinguish him from his son, and his grandson the conqueror at Bannockburn.

He was born in 1210, and on the death of Margaret of Norway in 1290, being

then in his eighty-first year, he became a claimant with John Baliol for the

crown of Scotland. [See BALIOL, JOHN.] On this occasion, he alleged that

more than fifty years before, or in 1238, while in the 28th year

of his age, when Alexander the Second was about to proceed on an expedition

against the western isles, and then despairing of heirs of his own body, he

was acknowledged by that monarch, in presence and with consent of his

barons, as the nearest heir in blood to the throne, but the birth of a son

to Alexander by his second wife, in 1241, put an end at that period to his

hopes of the succession. Lord Hailes thinks Brus’s allegation a fiction; Sir

Francis Palgrave, with fuller materials, certainly shows reasons for

believing it correct. [Documents Illustrative of Scottish History,

1837, Introduction, pp. xxiii - xxix.]

In 1252, on the

death of his mother the princess Isobel, he did homage to Henry the Third as

heir to her lands in England, and in 1255 he was constituted sheriff of

Cumberland and constable of the castle of Carlisle. The same year, on the

breaking up of the regency of the Comyn party, which was that of the

independent interest as being opposed to the English supremacy in Scotland,

he was appointed one of the fifteen regents of the kingdom, during the

minority of the young king, Alexander the Third. Nine years later, that is

in 1264, during the famous struggle of King Henry the Third with his barons

headed by Simon de Montfort, in conjunction with John Comyn and John de

Baliol, de Brus led a large Scottish force to the assistance of the English

monarch, who, however, was defeated at the battle of Lewes, 14th

May of that year, when de Brus was taken prisoner, along with Henry and his

son, Prince Edward. After the battle of Evesham, 5th August,

1265, which retrieved the fortunes of King Henry, Bruce was set at liberty,

and was reinstated in the governorship of Carlisle castle.

On the death of

Alexander the Third in 1286, a parliament assembled at Scone, 11th

April, in which a regency, consisting of six guardians of the realm, was

appointed, three for the country north of the Forth, namely, William Fraser

bishop of St. Andrews, Duncan earl of Fife, and Alexander Comyn earl of

Buchan; and three for the country south of the Forth, namely, Robert Wishart

bishop of Glasgow, John Comyn lord of Badenoch, and James the Steward of

Scotland. Then properly may be said to have commen ced the contest for the

succession to the crown, between the partisans of Brus and Baliol, although

these were not the only claimants. The heiress to the throne, Margaret,

granddaughter of Alexander and grand-niece of Edward the First, was still

alive and in Norway, but she was an infant, and the different competitors

began to collect their strength and indulge in ambitious hopes, in the

anticipation of a struggle for the sovereignty. The most powerful of the

Scottish barons met, September 20, 1286, at Turnberry, the castle of Robert

de Brus, earl of Carrick in right of his wife (see the following article),

son of Robert de Brus, the subject of this notice, lord of Annandale and

Cleveland. They were joined by two powerful English barons, Thomas de Clare,

brother of Gilbert, earl of Gloucester, brother-in-law of the lord of

Annandale, and Richard de Burgh, earl of Ulster. Among those assembled at

Turnberry were Patrick, earl of Dunbar, with his three sons; Walter Stewart,

earl of Menteith; de Brus’s own son, the earl of Carrick, and Bernard de

Brus; James, the high Steward of Scotland, who had married Cecilia, daughter

of Patrick, earl of Dunbar, with John, his brother; Angus, son of Donald the

lord of the Isles, and Alexander his son. “These barons,” says Tytler,

“whose influence could bring into the field the strength of almost the whole

of the west and south of Scotland, now entered into a bond or covenant, by

which it was declared that they would thenceforth adhere to and take part

with one another, on all occasions, and against all persons, saving their

allegiance to the king of England, and also their allegiance to him who

should gain the kingdom of Scotland by right of descent from King Alexander,

then lately deceased. Not long after this the number of the Scottish regents

was reduced to four, by the assassination of Duncan, earl of Fife, and the

death of the earl of Buchan; the Steward, another of the regents, pursuing

an interest at variance with the title of the young queen, joined the party

of de Brus, and heart-burnings and jealousies arose between the nobility and

the governors of the kingdom. These soon increased, and at length broke out

in open war between the parties of de Brus and Baliol, which for two years

after the death of the king continued its ravages in the country.” Tytler

adds that this war, hitherto unknown to our historians, is proved by

documents of unquestionable authority. [Hist. of Scotland, vol. i. p.

56 and notes.] It will be remembered, although the popular impression

is to the contrary, that at this period the Comyn party, to which belonged

John de Baliol, lord of Galloway, whose sister Marjory was the wife of the

Black Comyn and mother of the Red Comyn (afterwards slain by Robert de Brus),

were and had been the constant supporters of the Scottish or independent

interests, and the de Brus party, which appeared to be the strongest, had

all along been in alliance with England. A pleading of de Baliol, in old

Norman French, then the language of statee affairs both in England and

Scotland, addressed to Edward the First, during the suit for the crown, and

stating reasons why his claim was preferable to that of de Brus, is still

extant. The seventh and last of these reasons is that Brus had committed

acts of rebellion against the peace of the realm during the regency, by

assaulting the castles of Dumfries, Wigton, and a place called Bot... , [the

latter part of the name is obliterated], and expelling the troops of the

queen therefrom. [ Palgrave’s Documents, &c. Introduction. pp. lxxx,

lxxxi.]

In the

negotiations during the years 1289 and 1290, relative to the proposal of a

marriage between the infant queen and Edward, the young son of Edward the

First of England, the lord of Annandale was actively engaged, and with the

bishops of St. Andrews and Glasgow, and John Comyn, he was one of the

Scottish commissioners at the conference at Salisbury, who signed the treaty

there. Although it is reasonable to suppose that the anxiety manifested

throughout these negotiations, to avoid any concession prejudicial to the

independence of the Scottish crown was strongly felt by the parties then in

power, yet it would be unfair without further grounds to infer that the

nobles who were leagued against the Comyns were not as earnest for the same

result. On the death of Margaret, it is well known that King Edward

interfered in the settlement of the succession to the throne. Two of the

regents, William Fraser bishop of St. Andrews, and John Comyn lord of

Badenoch, had set aside their colleagues, the Steward and the bishop of

Glasgow, and had taken into their own hands the entire administration of the

realm. It was their policy to appoint John de Baliol to the vacant throne,

and on the 7th October 1290, before the report of the death of

the young queen had been certaily confirmed, Fraser write a letter to King

Edward recommending Baliol in a particular manner to his favour. By their

own authority the joint regents had nominated sub-guardians of the realm,

and delegated to them the right of maintaining order. These sub-guardians

had, in name of the two regents, adopted violent measures for endorcing

their authority in various parts of the kingdom, and especially in Moray. A

large portion of the nobles and community of Scotland were opposed to the

proceedings of the regents, and maintained the right of Robert fe Brus to

succeed to the crown. It now appears that the intervention of Edward the

First in the affairs of Scotland, which has been so much misunderstood by

historians, was caused not by the famous letter of Fishop Fraser, as has

commonly been supposed, but by three formal and regular appeals made to him

by three competent parties, namely ‘the seven earls of Scotland,’ Donald

earl of Mra, and Robert de Brus lord of Annandale. Claiming it as their

privilege, by immemorial custom, as a peculiar estate in the realm, to

appoint a king, whenever there was a vacancy, and to invest him with the

royal authority, the seven earls came forward and appealed, on the ground

that the regents were infringing, or intended to infringe, this their

constitutional franchise. Donald earl of Mar, one of the seven earls,

appealed against the unconstitutional appointment of sub-guardians, and

against the damages done by certain of these guardians in the lands of

Moray, and Robert de Brus lord of Annandale appealed against the understood

intention of the regents to appoint Baliol to the throne, and thus violate

his rights, and the rights of the seven earls. [See Palgrav’e Documents

Illustrative of Scottish History.] The consequence of these appeals was

the famous summons of the English monarch that the nobility and clergy of

the Scottish kingdom should meet him at Norham, in the English territories,

on the 10th of May 1291. Having accordingly met him at the time

and place appointed, after declaring that he was ready to do justice to all

the competitors, he required them, in the first place, to acknowledge him as

lord paramount of the kingdom. To this unexpected demand no reply for a time

was given. At length some one observed that it was impossible to give an

answer whilst the throne continued vacant. “By holy Edward, whose crown I

wear,” said the imperious king, “I will vindicate my just rights or perish

in the attempt.” He then granted them three weeks for deliberation.

On the 2d of June

the Scottish barons and clergy again met King Edward at Upsettlington, when

eight competitors for the cdrown were present. These were, Robert de Brus,

lord of Annandale; Florence, count of Holland; John de Hastings; Patrick de

Dunbar, earl of March; William de Ros; William de Vesey; Robert de Pinckeny;

and Nicholas de Soulis. John de Baliol, lord of Galloway, attended next day.

The chancellor of England, addressing himself to de Brus, demanded whether

he acknowledged Edward as lord paramount of Scotland; and he expressly and

publicly declared that he did. On the same question being put to the other

competitors, the same answer was given. Baliol, on his appearance on the

following day, after some hesitation, also acknowledged the same. These

preliminary steps being taken, after a full investigation of the claims of

all the candidates, Edward, upwards of seventeen months after the

commencement of the inquest, pronounced in favour of Baliol, on the 17th

November 1292. There is no reason to believe that in this decision Edward

was otherwise than influenced by a just regard to the true law of

succession; and there are many considerations that would have induced him,

and he was understood privately to incline, to favour the cause of de Brus.

The appeals of the

Seven Earls having, as we have seen, constituted the foundation of all the

proceedings of Edward above recorded, it may be proper here to inquire, in

what sense did the Seven Earls and the others appeal to Edward? Was it in

the sense in which he accepted the appeal, – namely, as an appeal of a

portion of the community of Scotland to him as their lawful superior; and

was the reluctance which, we are informed, the Scottish nobility and clergy

exhibited to comply with his demand, that they should acknowledge him as

Lord Paramount, the mere reluctance of the rest of the cummunity to give

their assent to a proposition already virtually admitted by the appellants;

or, as possibly may have been the case, was it the reluctance also of the

appellants themselves, to make a formal and open averment of a proposition

necessarily implied in their appeal, but which, as they knew it to be

unpopular, they would have been glad to escape avowing in so express and

glaring a manner, as that in which the wily Edward made them do it?

Sir Francis

Palgrave, who, with so much ability, and with the advantage of the

additional light afforded by the documents which he has given to the world,

has revived the long obsolete question of the English supremacy over

Scotland, holds that, in appealing as they did to Edward, de Brus and the

Seven Earls meant to admit his title to give judgment as the lawful

Over-Lord of the Scottish kingdom. They submitted to Edward’s judgment, he

says, “not as to an arbitrator selected to determine a contested question,

but as to a lawful superior whose protection and defence they implored.” [Palgrave,

Documents, &c. Introduction, p. xxi.] And farther on, expanding the same

remark, he says, “The Scottish writers upon Scottish history, warmed by the

courage and heroism of de Brus and Wallace, as represented in the poetry and

popular legends and traditions of their country, have characterized the

repeated submissions to the English king as acts of disgrace, and stains

upon the national honour. But the justice of the cause must be judged

according to the conscience of the parties; and if the prelates, the peers,

the knights, the freeholders, and the burgesses of Scotland, believed that

Edward was their Over-Lord, it is not their obedience, but the withdrawing

it, that should be censured by posterity. ... There is not any reason for

believing that, until the era of Wallace, there was any insincerity on the

part of the noble Normans, the stalwart Flemings, the sturdy Northumbrian

Angles, and the aboriginal Britons of Strathclyde and Reged, whom we

erroneously designate as Scots – in admitting the legal supremacy of the

English crown, until the attempts made by Edward I. to extend the

incidents of that supremacy beyond their legal bounds provoked a

resistance deserved by such abuse.”

Now, so far as the

appeals of de Brus and the Seven Earls are concerned, it cannot be denied

but that Sir Francis Palgrave is in the right. The language of the appeals

themselves it would be difficult to interpret otherwise than as a

recognition of the superior authority of the crown of England over the

Scottish nation, although it may certainly be remarked that the writers seem

to have been studious to avoid any explicit statement of that fact in so

many words. The question, however, as regards de Brus, would be set at rest,

if it could be shown that Sir Francis Palgrave is right in supposing that

the following letter, published by him for the first time, along with the

appeals, in the volume above referred to, was written by de Brus. The

letter, which is written in Norman Franch, is evidently that of a competitor

for the Scottish crown, who wishes to ingratiate himself with Edward by

inordinate eagerness to admit his claim to the feudal superiority over

Scotland. We translate as literally as the gaps will permit: – “I have heard

from my father, and from ancient men of the time of King David, that there

was war between the king of England and king David. And in that time that

Northumberland was lost, there was a peace made between the king of England

and the king of Scotland; to wit that, if the king of Scotland should ever

in anywise refuse obedience to the king of England, or to his crown, then

the Seven Earls of Scotland should be bound by oath . . . to the king of

England, and to his crown. . . in . . . Afterwards . . . obediences were

made. But afterwards came King Richard, and sold the homage of the king of

Scotland. . . We do not think that this sale can be valid; for well is the

king of England who is so wise, and his council also, able to advise,

whether the crown can be dismembered of such a member. And seeing that the

crown ought to be kept entire, let it be known to him by Elias de Hanville,

that At what hour he will make his demand regularly, I will obey him, and

will aid him with myself, and all my friends, and all my lineage. . . my

friends will do. And I pray your grace for my right, and for the truth which

I wish to manifest before you; and meanwhile I . . . by speaking with the

ancient men of the land, to find out the evidence of your interests, as . .

.”

Sir Francis

Palgrave’s statement, however, that “the prelates, the peers, the knights,

the freeholders, and the burgesses of Scotland, believed that Edward was

their Over-lord,” is too sweeeping. It ignores the fact, that a feeling had

existed with a part at least of the Scottish community, for nearly a hundred

and fifty years previous to this memorable epoch, of antipathy to this very

claim of English supremacy. There was a germ and a root of repugnance to

England in the Celtic portion of the nation. But a network of Norman

colonization had overspread nearly the whole British island, which remained

entire and connected throughout its whole length, so that the northern part

of it, i.e. the Scoto-Normans, did not feel themselves yet separated

from the southern part of it, i.e. the Anglo-Normans. Besides this,

another strong tie co-operated in enabling England to grapple Scotland

towards herself. This was the traditional claim of legal supremacy asserted

by England over Scotland, a claim which as Sir Francis Palgrave’s

investigations have made clear, had, whether well or ill founded, a real

place in the beliefs of the period. Edward the First seems clearly to have

believed that, in virtue of certain old transactions, he, as king of

England, had a claim upon the allegiance of the people of Scotland. Looked

at from this point of view, therefore, his crime in the matter of Scotland

may have been, as Sir Francis Palgrave calls it, a mere attempt to “extend

the incidents of his legal supremacy beyond their legal bounds.” On the

other hand, too, it seems pretty clear that, among the Scottish nobles,

there was, during the whole of the period referred to, no decided conviction

that the claim of English supremacy was illegal in any absurd degree. The

feeling of at least a portion of them, relative to this claim, seems to have

been rather a desire to disencumber themselves of it, than such a contempt

for it as would have been inspired by a sincere belief that it was the mere

pretext of an invader. Hence it is found that, during the whole of that

period, though inclined to escape the claim of homage to England whenever

they could, on the least pressure they were found ready to yield to it.

The lordship of

Annandale being held, as already stated, by the tenure of military service,

to avoid doing homage to his successful rival, Robert de Brus resigned it to

his eldest son, retaining only for himself his English estates. “I am

Baliol’s sovereign, not Baliol mine,” said the proud baron, “and rather than

consent to such a homage, I resign my lands in Annandale to my son, the earl

of Carrick.” He seems thenceforth to have lived in retirement. He died in

1295, at his castle of Lochmaben, at the age of eighty-five. He had married

an Englishwoman, Isabel, daughter of Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester,

one of the most powerful barons of England, and by her he had Robert de Brus,

earl of Carrick, two other sons, and a daughter.

BRUCE, or DE BRUS,

ROBERT,

eldest son of the competitor, and father of King Robert the Bruce,

accompanied King Edward the First of England to Palestine in 1269, and

appears to have enjoyed the confidence and friendship of that monarch. On

his return, he married, in 1271, Margaret, the young and beautiful countess

of Carrick, whose husband, Adam de Kilconath, (Kilconquhar?) earl of Carrick

in her right, was slain in the Holy Land. By this lady, who was the only

child of Nigel, earl of Carrick and lord of Turnberry, and Margaret, a

daughter of Walter, the high steward of Scotland, de Brus had his celebrated

son Robert, afyterwards king of Scotland; Edward de Brus, lord of Galloway,

crowned king of Ireland in 1316; three other sons and seven daughters.

The circumstances

attending this marriage as related by our historians, are of as singular and

romantic a character as any in Scottish annals. One day in the autumn of

1271, while Martha, as she is generally called, though Marjory, or Margaret,

appears to have been her proper name, countess of Carrick in her own right,

was engaged in the exercise of hunting, surrounded by a retinue of her

squires and damsels, in the grounds adjoining her castle of Turnberry in

Ayrshire, the ruins of which still remain, she accidently met with de Brus,

then about thirty years of age, who had just returned from the Holy Land,

and was passing on horseback through her domains. Struck by his noble

figure, the young countess invited the knight to join her in the chase and

to be her guest for a time. Aware of the peril he encountered in paying too

much attention to a ward of the king, as the countess was, de Brus, it is

said, declined the invitation so courteously given, when, at a signal from

the countess, her retinue closed in around him, and the lady, seizing his

bridle reins, led him off, with gentle violence, to her castle at Turnberry.

He was thus constrained to partake of the hospitality of the countess, and,

after fifteen days’ residence with her, he married her, without the

knowledge of the relatives of either party or the consent of the king,

which, as she was a ward of the crown, ought to have been previously

obtained. So flagrant a violation of his feudal rights provoked even the

good tempered Alexander the Third, and the castle and estates of the

countess were instantly seized. By the intercession of friends, however, the

king was induced to pardon the youthful offenders, first inflicting on the

lady the payment of a heavy fine. Her husband became in her right earl of

Carrick, and their eldest son was Robert de Brus, the greatest of our

monarchs, this union being thus an auspicious event for Scotland. Such is

the tale told by our historians, and in most points it is true, but to take

away somewhat from its romance, one account, which seems the most probable,

states that de Brus had been the companion in the Holy Land, as well as the

fellow-crusader of the lady’s first husband, Adam de Kilconath, and it is

not unlikely that, on the death of the latter without issue, he returned to

Scotland with the design of marrying his widow, who, besides being young and

beautiful, had a proud title and extensive estates to confer on whomsoever

she bestowed her hand. His solitary ride through the woods of Turnberry was

thus not without an object.

When the future

monarch of Scotland was yet a minor, his father, following his grandfather’s

example, to avoid doing homage to Baliol, resigned to his son the earldom of

Carrick, which he held in right of his wife, just then deceased. The

youthful de Brus, on obtaining the title and lands, immediately swore fealty

to Baliol as his lawful sovereign. His father shortly after retired to

England, leaving the administration of the family estates of Annandale also

in his hands. In 1295, the same year in which the aged de Brus, the

competitor, died, Edward the First appointed de Brus the elder, the father

of king Robert, constable of the castle of Carlisle. In 1296, when Baliol,

driven to resistance by the galling yoke which Edward endeavoured to force

upon him, (by attempting to exercise a jurisdiction in Scottish affairs

which none of his predecessors had ever pretended to possess,) revolted from

his authority, and, assisted by the Comyns, took up arms to assert his

independence, de Brus the elder, cherishing no doubt, the natural hope that

as the next heir to the throne he might, on the event of the overthrow and

deposition of his rival, receive the vacant crown from thre English monarch,

accompanied Edward’s expedition into Scotland, and with his party, which was

numerous and powerful, gave their assistance to the English king. Our

Scottish historians indeed assert that a promise to this effect was made to

him by Edward, but it receives no countenance in English history, and is

quite inconsistent with what we know of Edward’s character or purposes.

Baliol, in consequence, seized upon the lordship of Annandale, and bestowed

it on John Comyn, earl of Buchan, who immediately took possession of the

castle of Lochmaben.

After the decisive

battle of Dunbar, 28th April 1296, in which the Scottish army was

defeated, and Baliol compelled to surrender the sovereignty, it is said by

the writers referred to that the elder Bruce reminded Edward of his promise

to bestow on him the vacant crown, and receiverd the following reply: “What!

Have I nothing else to do than to conquer kingdoms for you?” But although

Tytler does not venture to omit this incident, later writers have so far

treated it as doubtful as to soften the request into a simple application,

without reference to any previous promise, a mode of regarding it more

consistent with probability and with the well known character for probity

borne by Edward. [Papers on Robert Bruce in Lowe’s Edinburgh Magazine,

March 1848, p. 345.] After this he seems to have retired to his English

estates. In 1297, Sir William Wallace, one of the greatest heroes of which

the annals of any nation can boast, nobly stood forward as the defender of

his country’s freedom; but his patriotic achievements failed to rouse de

Brus from his inactivity, or to induce him to consider Wallace as seeking

more than either to restore Baliol or as aspiring to the throne himself. In

the fatal campaign of 1298, which concluded with the disastrous battle of

Falkirk, our Scottish historians represent Brus the son to have accompanied

the English monarch, and to have fought in his service against his

countrymen. After a gallant resistance, they assert that Wallace was

compelled to retreat along the banks of the Carron, pursued by de Brus at

the head of the Galloway men, his vassals. Here a conference is represented

to have taken place between the two leaders, which ended in de Brus’s

resolving to forsake the cause of Edward.

Wallace is

described as having upbraided de Brus as the mean hireling of a foreign

master, who, to gratify his ambition, had sacrificed the welfare and

independence of his native land. He is represented to have urged him to

assume the post to which he was entitled by his birth and fortune, and

either deliver his country from the bondage and oppression of Edward, or

gloriously fall in asserting its liberties. By Wallace’s reproaches and

remonstrances, de Brus, it is said, was melted into tears, and swore to

embrace the cause of his oppressed country. Such is the story of Wynton and

Fordun, and of course of Boece, Blind Harry, and Buchanan, and it may be

accepted as one of the most curious instances that could be adduced of the

operation of the mythical or dramaturgic faculty to the falsification of

history. Not only do the old Scottish writers make Bruce fight on Edward’s

side at the battle of Falkirk, but in contradicition to all possibility they

make him and Anthony Beck, bishop of Durham, jointly decide the fate of the

battle against the Scots. It is certain, however, that the younger de Brus

was not at the battle of Falkirk at all, but, as stated by an author who was

in Scotland and with Edward’s force at the time (Heningford), he was then in

guard of the castle of Ayr, in the interest of the Scottish cause maintained

at Falkirk by Wallace. Since this fazct was brought to light by Lord Hailes,

writers – including a recent translator of Buchanan – have represented that

it was de Brus the father who was present at Falkirk and had the interview

with Wallace, but there is no warrant in the older historians for this

transposition of the person referred to. All early accounts state that de

Brus the father ceased to take any interest in Scottish affairs after the

refusal of Edward to accede to his request for the vacant crown. It could

not be de Brus the elder who fought on the side of Edward at Falkirk at the

head of his Galloway vassals, as th original story has it, when he had no

vassals in Galloway, and when all Galloway was then in the power of the

patriots, with young de Brus his son, at the head of his Carrick tenatry, as

their leader. The part moreover assigned to young de Brus in that fight,

viz., the moving behind the Scottish ‘schiltrons’ and attacking them

in the rear, is precisely that described by the historian eye-witness to

have been taken by Sir Ralph de Basset, who was second in command to Anthony

a Beck, the warlike bishop of Durham. It was this Sir Ralph, and not young

de Brus that, as described by Synton (who wrote 110 years after the event) –

“With Sir

Anton the Beck, a wily man,

(Of Durham bishop he was than),

About ane hill a well far way,

Out of that stour then pricked they.

There they come on, and laid on fast;

Sae made they the discomfiture.”

It is not impossible,

therefore, that the whole story may have originated in a blunder in some old

document, – a circumstance not uncommon in copying the writings of that age,

– and that Sir R. Basset may have been misread or miscopied, as

Sir R. Brus. [A singular instance of this nature occurs in a document

referred to in the next life, where Irvine is rendered Sir William Wallace,

thus ‘Escrit a Irewin,’ (written at Irvine) for ‘

escrit a Sirewm,’

afterwards divided into Sire Wm., and again elongated into Sire Willaume, as

printed in Rymer. Hailes naturally supposed it to mean Sir William Wallace.]

The famous meeting, therefore, of de Brus with Wallace after the battle of

Falkirk – the most exquisite, it is admitted, of Scottish legends – is a

mythus, an imaginary fact or circumstance, in which the popular national

feeling regarding the two heroes has bodied itself forth. At the death of de

Brus in 1304, he transmitted his English estates to his son, the future king

of Scotland, who was then thirty years of age; whether, at the same time, he

bequeathed to him a nobler legacy, namely, that of atonement and true

patriotism, exhorting him, with his latest breath, to avenge the injuries of

his suffering country, and to re-establish the independence of Scotland, as

is asserted by authors in connection with the legend above referred to, is

more than doubtful. This at least is clear, that the crown of Scotland, to

which both conceived they had an undoubted right, was never out of the view

of the latter, who, in gaining it, secured at the same time, the

independence of his kingdom.

The following seal

of Robert de Brus the father represents only the arms of the ancient earldom

of Carrick:

BRUCE, or

DE BRUS, ROBERT,

the restorer of the national monarchy, eldest son and second child of the

preceding, and of the Lady Martha, sole daughter of Nigel, earl of Carrick,

was born on the 121th of July 1274. It has been generally believed that

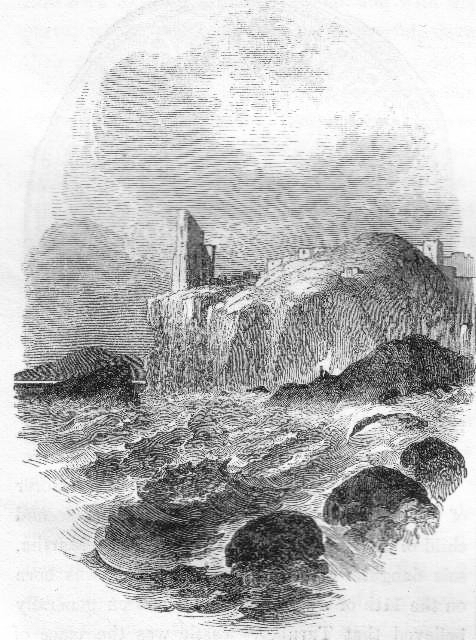

Turnberry castle was the place of his birth, and in his Lord of the Isles,

canto v., stanza 33, Sir Walter Scott assumes this to have been the case;

but there is no evidence on the subject. Tradition on the contrary, if we

may assume it to be represented by the mendacious Boece (Bellenden’s

Translation, xiv. 5.), describes him as “an Englishman born;” and that

excellent authority, Collins’ Peerage (article earl of Aylesbury), expressly

states that on his return from the Holy Land, de Brus went to reside in

England. Although, however, the lines of welcome to its halls on the

occasion of his return from Rachrine, described in that poem,

“Once more behold the floor I trod

In tottering infancy!

And there the vaulted arch whose sound

Echoed my joyous shout and bound

In boyhood, and that rung around

To youth’s unthinking glee!”

cannot be

literally true, there can be no doubt that Turnberry castle became the abode

of his father during a part of his boyhood, and whilst the events, described

in the life of his grandfather as occurring there from 1286 to 1290, were

taking place.

In

conformity with the practice of the barons of that age to send their

children to the household of some noble, superior in rank, there to acquire

the graces of society and the art of arms, young de Brus appears to have

been placed in the household of Edward, king of England, where he was

trained in those exercises of war and chivalry for which he became

afterwards so distinguished. That this was the consequence of the early

friendship that existed between his father and that monarch, of which the

language of a deed still extant bears witness, and not because the family of

the elder de Burs was considered as aliens to Scotland, appears from the

circumstance, that his grandfather continued to reside until his death in

the ancestral castle of Lochmaben, and that all his sisters, six in number,

were in early life married to Scottish barons. In 1293, when just entering

his seventeenth year, young de Brus was infefted in his mother’s lands, and

in the title of earl of Carrick, which devolved on him through her, lately

deceased, and he rendered homage to Baliol for the same at his second

parliament, held at Stirling in August and September of that year. One chief

cause of this infeftment was the unwillingness of his father to acknowledge

the title of Baliol. At the time this took place, as we are informed in the

Scoto Chronicle, young Robert was “a young man in King Edward’s chamber,”

when he was sent for by his father. He also conferred on him the

administration of his lands in Annandale at the same time. In 1294, on the

occasion of a war breaking out between England and France, a writ appears to

have been sent to him as earl of Carrick by Edward, to serve in person

during the expected campaign, but whether he complied with it does not

appear. He seems to have taken the same part as his father in aid of the

English monarch, during his invasion of Scotland in 1296, on the occasion of

the revolt of Baliol, which led to their castle of Lochmaben in Annandale

being temporarily seized by Comyn, earl of Buchan, leader of the Scottish

army; and after the decisive fight of Dunbar, 28th April, he was

employed to receive for Edward the submissions of his own men of Carrick. In

August of the same year, when Edward held a parliament at Berwick for the

settlement of Scotland, Bruce, then earl of Carrick, with the rest of the

Scots nobility, renewed his oath of homage to the English monarch. Up to and

ever after this period, it is probable that not only both father and son but

all the Scottish magnates of their party, who joined with them in that act

of homage, entertained the expectation that when all was tranquilly settled

in Scotland, the English king would confer the government of that kingdom as

a king-fief of his crown upon the former. The idea of his ruling it, even as

lord paramount, except through the instrumentality of a native prince, was

in antagonism not only to all historical precedent, but must have been

repugnant to every feeling of nationality in their bosom. If so, however,

the establishment by Edward, on his leaving for England later in the autumn

of that year, of the earl de Warenne as governor of Scotland, with

Cressingham and Ormesby as treasurer and justiciary, proved the futility of

their hopes.

That

young de Brus was dissatisfied with this settlement of the kingdom it was

but natural to suppose, and on the appearance of Wallace, in the following

summer (1297), carrying on a private warfare against the English in the

south-west of Scotland, in which he was joined by various chiefs in the

neighbourhood, his conduct became so equivocal, that, as Hemingford relates,

the English wardens of the western marches summoned him to Carlisle to renew

his oath of fidelity to Edward. Probably being then unprepared to act on the

offensive, he proceeded there with his vassals, and took a solemn oath on

the consecrated host and the sword of Thomas à Becket, to assist Edward

against the Scots and all his enemies. To prove his sincerity, on his return

to Annandale he made an inroad with his armed vassals upon the lands of

William lord Douglas, knight of Liddesdale, one of the insurgent lords; and,

after wasting them, carried off his wife and children to his castle at

Turnberry.

No

sooner, however, was the danger over than the correctness of their

suspicions was manifested by his joining the conspiracy of the Scottish

leaders, and attempting on his return to Carrick to induce his father’s

vassals to rise with him. In this perhaps he was not so much an active as a

passive agent. The revolt against the English rule had become so general,

says Hemingford, as entirely to assume a national character, and the vassals

of the barons could not be restrained by their chiefs from adhering to it.

By opposing it his own safety was likely to be compromised, and it seemed

probable that all chance of his claim to the throne ever being recognised by

the nation would be cut off. There seems to have been strong hopes held out

to him that the insurgents would adopt his cause. It was publicly at this

time reported, according to Hemingford, that he aspired to the throne. All

the leaders of the insurrection, except Wallace and Sir Andrew Moray, were

those who had invariably supported the claims of his family. Wishart, bishop

of Glasgow, who had counselled their rising, was hie firm friend, and the

Comyns, who were his rivals in their own right and in that of Baliol, were

with their partisans in confinement in England. The men of Annandale,

however, at first hesitated, asked a day to consider the matter, and quietly

dispersed to their homes during the night. With his own vassals of Carrick,

however, he took up arms, and might, notwithstanding of his youth, have

rendered important service to the national cause, had unity prevailed in

their counsels, and had not the English forces been too active to permit it.

Wallace had determined to support the cause of Baliol. He was the soul of

the party, and not a few of the insurgents joined in his views. The Comyns

also had adherents in the camp. The Scottish forces were numerous and

strongly posted, but their leaders were actuated by opposing views. First

one, then others of them,, left the camp and went over to the English. Being

thus taken at disadvantage by an army under Sir Henry Percy and Sir Robert

Clifford, commanding in Scotland, the confederates were constrained to yield

upon conditions at Irvine, on the 9th of July 1297. The document

embodying their submission has been published in its original Norman French

by Sir F. Palgrave, and is that referred to in the note in the preceding

life as having contained an error in transcription. On this occasion so much

difficulty was felt by the English commanders with respect to de Brus, that,

as appears by another document of the same date, his daughter Marjory, then

about four or five years of age, was required to be delivered to them as an

hostage, and three magnates, of whom two were parties to the convention,

became joint securities for his loyalty “with their lives, limbs, and

estates,” until that hostage should be delivered into their hands. The

Marjory was his only child by his first marriage with the daughter of the

earl of Mar, who survived this bereavement only for a few months. The

conduct of Wallace on this occasion shows a fierce and intractable

disposition. although included in the capitulation he refused to accede to

its terms. Ascribing the arrangement to the counsell of Wishart, bishop of

Glasgow, he set fire to his house, plundered all his goods, and led his

family captive. The other barons honourably fulfilled their engagement.

In

the subsequent struggles of Wallace and his party, de Brus took no active

part; but in 1298, when Edward entered Scotland with a formidable army, he

shut himself up in the castle of Ayr, and maintained a doubtful neutrality.

After the defeat of Wallace at Falkirk, Edward was about to attack the

castle of Ayr, when de Brus, dreading the consequences, razed it to the

ground, and retired into the recesses of Carrick. In 1298, when Wallace had

resigned the regency, John Comyn of Badenoch and Sir John Soulis were chosen

guardians of the kingdom. About a year afterwards, Lamberton, bishop of St.

Andrews, and the earl of Carrick then only in his twenty-fifty year, were,

by general consent, added to the number.

The

conduct of de Brus, at this juncture, as throughout the entire period prior

to his assumption of the crown, not being understood, has excited the wonder

and regret of posterity. supple, dexterous, and accommodating, – now in arms

for his country, and then leagued with her oppressors, – now swearing fealty

to the English king, and again accepting the guardianship of Scotland in the

name of Baliol, it seems to require all the energy, perseverance, and

consummate prudence and valour of after years to redeem his character from

the charge of apparent and culpable weakness. De Brus the guardian of

Scotland in the name of Baliol! Says Lord Hailes, is one of those historical

phenomena which are inexplicable. Yet this conduct we have attempted to

explain, and in part to vindicate, by the peculiarity of his circumstances,

which necessitated a course different from what he would have chosen. His

grandfather, after vainly endeavouring to establish his pretensions to the

throne of Scotland, had quietly acquiesced in the elevation of Baliol. His

father, sometime earl of Carrick, had submitted uniformly and implicitly to

the superior ascendency of the English monarch. Bruce, therefore, though

convinced of his right to the Scottish throne, and determined to assert it,

could not in the meantime, with decency or hope of success, urge a claim in

his own person. In doing so he would have had to contend with a rival who

was at that time one of the most powerful men in the kingdom. Baliol had

renounced for ever all claim for himself, and his son was in captivity; but

the claims and hopes of his family centered in John Comyn, commonly called

the Red Comyn, the son of his sister Marjory, who was allied to many of the

noblest families in Scotland and England, and who, by the decision of

Edward, possessed, in succession, a clear right to the Scottish crown.

Between the families of Bruce and Comyn there had existed for many years all

the jealousy and hatred which rival and irreconcilable interests could

create. The movements of both families, not only during the contests which

occurred between the abdication of Baliol and the death of Wallace but long

afterwards, seem to have been decided rather by a regard to family interests

than the good of their country. They were uniformly ranged on opposite

sides, with the exception of the brief period now referred to, when Bruce

and Comyn were associated in the regency of the kingdom.

All

writers seem to think that this coalition had been mainly produced by a

desire to crush Wallace, whose patriotism and influence endangered their

common pretensions, and that that end once gained they returned to their

former course of factions opposition and strife. That the existence on the

part of both of this feeling is true, and that, as respects Comyn at least,

this was the ruling motive, we are not prepared to deny. It was only the

leaders of the army, however, who refused to serve under Wallace. But de

Brus was not with the army, nor in communication with it, until some time

after the appointment of Comyn as guardian. the battle of Falkirk was fought

on 22d July 1298; Wallace’s resignation followed immediately thereafter, as

well as the appointment of Comyn as guardian, whilst the first appearance of

the name of de Brus in connection with the office is on 13th Nov.

1299. It has been supposed that de Brus was pressed upon the other guardians

by Lamberton, the primate, as a condition of his (Lamberton’s) accepting the

same office, and for the sake of union and conciliation, and Lamberton was a

friend of Wallace raised to the primacy by the determined will of that

patriot alone [Palgrave documents.] A more satisfactory explanation

of his conduct may therefore be found in the not improbable conjecture, that

the regency of 1299 was the result of a compromise in which the claims of

Baliol, then in hopeless captivity in England, were understood to be

abandoned. The joint guardianship, whether established or not on this

understanding, lasted only for a short time. Lamberton and de Soulis went

over to France as commissioners, with five others, there to watch over the

national interests. A cautious and far-seeing, but selfish policy, must have

taken alarm on the prosperous appearance which Baliol’s affairs soon

afterwards began to assume, and probably offence at the proceedings of his

representatives thereupon. When the cause of the late imprisoned and

abdicated king was taken up by the courts of France and Rome; when the

genuineness of the deed of his resignation of the throne was denied by the

Scottish emissaries at the latter court; when his person was released from

prison, and delivered over to the Pope’s nuncio at Witsand, 18th

July 1299; and when a bull admonitory, in his interest, was served on Edward

himself, by no less a personage than the archbishop of Canterbury (June

1300), we find that soon thereafter, – his lands of Annandale and Carrick

having in the meantime been laid waste by the army of Edward, – de Brus once

more abandoned a cause which had become again not that of his country but of

his rival, and made his peace with Edward, by surrendering himself to John

de St. John, the English warden of the western marches.

This

view of the character of the guardianship of de Brus, amongst other proofs

too minute for detail, receives confirmation from the circumstance that in

the only public transaction occurring during its brief existence of which

authentic documents have descended to us, namely, the adjustment of a truce

with Edward, no mention is made by either party of Baliol as king of

Scotland. During the three successive campaigns which took place previous to

the final subjugation of Scotland and the submission of the Comyns in 1304,

de Brus continued faithful to Edward. In all the proceedings which ensued

upon that occasion, de Brus was treated by Edward with favour and

confidence, and the settlement of Scotland, was arranged by the English king

on the plan recommended by de Brus.

On

the death of his father in 1304 he received possession of his lands in

Annandale and in England, and became one of the most powerful of the

northern barons. There is no evidence that up to the death of Comyn in

1305-6 de Brus had entertained serious thoughts of attempting to assert his

right to the Scottish crown. He certainly was occupied in strengthening his

friendships by bonds of the character of those that were common in that age,

and that with the ulterior object of improving any occasion that might arise

for this end. But his knowledge of the character of Edward, and the

closeness with which his proceedings were watched, were likely to induce him

to postpone all hostile projects until more favourable circumstances should

arise.

The

murder of John Comyn, younger of Badenoch, 10th February 1305-6,

is one of those passages in the obscure history of that period which has

exercised the patience and tried the candour of historians. The

contradictory and most improbable details of this event given by our

Scottish historians, written as they were long after the event took place,

can only be regarded as the embodiment and embellishment of national

traditions, and unfortunately the contemporary writers of England are silent

as to nearly all but the fact itself, and the accounts of later ones are as

difficult to reconcile with probability as those of the Scottish. Dismissing

not a few particulars now proved to be either impossible or false, the

circumstances which these historians relate as having led to and accompanied

this murder are as follows: That at a conference which took place between

the rivals at Stirling, de Brus, after lamenting the misery to which the

kingdom was reduced, made to him this proposal: – “Support,” says he, “my

title to the throne, and I will give you all my lands; or bestow on me your

lands, and I shall support your claim;” that Comyn cheerfully acceded to the

former alternative, waiving his own claims in favour of his rival; that a

formal bond was, in consequence, drawn up and signed by the parties; that de

Brus returned to London, matters not being yet matured sufficiently for open

resistance to the English; and that Comyn, anxious to regain the favour of

Edward, betrayed the plot to that monarch, and transmitted to him the

agreement signed by de Brus.

It

is added that King Edward, on receiving this information, cherishing the

design not only of seizing his person, but of involving him and his brothers

in one common destruction, was so imprudent as to discover his purpose to

some of the nobles of his court; that that very night the earl of

Gloucester, under pretence of repaying a loan, sent de Brus a purse of money

and a pair of gilded spurs – a hint which the latter understood; and,

accompanied by a single attendant, he took horse and escaped with all speed

into Scotland; that when near the Solway sands, he met a messenger

travelling alone, whom he recognised as a follower of Comyn; that his

suspicions were now awakened, and slaying the courier, he possessed himself

of his despatches, in which he found further proofs of Comyn’s treachery,

accompanied by a recommendation to Edward to put his rival to instant death;

that Bruce proceeded hastily on his journey, and repairing to Dumfries,

requested a private interview with Comyn, which was held February 4, 1305,

in the church of the Minorite Friars; that at first the meeting was

friendly, and the two barons walked up towards the high altar together; that

Bruce accused his rival of having betrayed their agreement to Edward, – “It

is a falsehood you utter,” said Comyn; and Bruce, without uttering a word,

drew his dagger and stabbed him to the heart; that hastening instantly from

the church, he rejoined his attendants, who were waiting for him without;

and that seeing him pale and agitated, they eagerly inquired the cause, – “I

doubt I have slain the red Comyn,” was his answer, “You doubt!” cried Sir

Thomas Kirkpatrick fiercely, “Is that a matter to be left to doubt? I’se mak

siccar,” (I will make sure;) and rushing into the church with Sir James

Lindesay and Sir Christopher Seton, they found the wounded man, and

immediately despatched him, slaying, at the same time, Sir Robert Comyn, his

uncle, who tried to defend him. Lord Hailes, however, investigated this

obscure transaction in 1767, with his usual impartiality and discrimination,

and the conclusions at which he arrived have not been invalidated but rather

confirmed by subsequent researches.

We

concur with him in thinking it was most improbable that de Brus should have

made such a proposal to Comyn as is there stated, or that Comyn could

suppose him to be sincere in doing so. Fordun does not say which alternative

Comyn accepted. Barbour makes the proposal to have come from Comyn. The

answer given by de Brus was, “I will take the crown; it is mine of right;”

an answer likely to revive the old contention. Barbour and Fordun represent

the agreement to have been by indenture, of which each held a copy signed by

the other – a most extraordinary circumstance, as they must have called a

third party. Winton, on the other hand, describes it as a mere conversation

as they were “riding fra Stirling.” It is most improbable that Edward, in

possession of such a document, should have concealed or delayed his purpose

of apprehending de Brus for a single day. Barbour reports that on receiving

Comyn’s part of the indenture Edward summoned a parliament, at which de Brus

appeared; – that he there exhibited the indenture, and accused de Brus of

treason; – and that de Brus asked to look at the paper till next day, and

then disappeared. Of course we know there was no such parliament, nor would

that be the mode of procedure at one. Not less unlikely is it that Edward

would in a moment of unguarded festivity reveal his purpose against de Brus,

if he was, as is stated, anxious to secure his absent brother. It is

altogether incomprehensible that the king’s son-in-;law Ralph de Monthermer,

called by courtesy the earl of Gloucester, should have betrayed the secrets

of his sovereign and benefactor. Our historians have, evidently under

mistake, meant this for the previous earl’s father, who was a relation of de

Brus’s mother. The purse of money and pair of gilded spurs should be “twelve

pence and a pair of spurs,” as in Fordun, a most mysterious and improbable

restitution and mode of communication of danger.

The

whole antecedents would appear to be prepared, under the inventive powers of

tradition, to account for the murder of Comyn as an act contemplated

beforehand, whereas it is most evident that it was as unexpected on the part

of de Brus as on that of his victim. It was a hasty quarrel between two

proud-spirited rivals. De Brus had made no preparations to assert his

pretensions to the crown, nor had he a single castle except Kildrummie in

Aberdeenshire at his disposal. Amidst a mass of contradictory

improbabilities one genuine public contemporary document is worth a hundred

conjectures. In his first public instrument after the slaughter of Comyn,

King Edward expressly says, that he reposed entire confidence in de Brus [Faed.

ii. 938]. It is not easy to see how he could have done so, if he were

possessed of written evidence to prove that the intentions of de Brus were

hostile. It was as little likely that de Brus could have known Comyn was to

be present at Dumfries as that he would have proposed a sanctuary – a place

so tremendous in the notions of those days – for the scene of action. It is

probable, however, that Comyn might have been endeavouring to instil some

suspicions into the mind of Edward from Jealousy of de Brus; and indeed

there is a hint to this effect given by Hemingford, the most authentic

because the best informed contemporary, and that reports of these might have

reached the ears of de Brus or been referred to by Edward himself. On

meeting Comyn, therefore, de Brus demanded a private interview and an

explanation. In their conversation some hot words took place, and de Brus

struck Comyn with his dagger. The impetuous zeal of his followers aggravated

the crime, and gave to the whole transaction the appearance of premeditated

assassination. Such is the conclusion at which we have been compelled to

arrive, after a careful consideration of all the circumstances of an event

which decided de Brus’s destiny.

Two

months thereafter, March 27, Bruce, as we shall now call him, was crowned

king at Scone. The whole proceedings indicate haste and lack of preparation.

The regalia of Scotland, with the sacred stone and the regal mantle, had

been carried off by Edward in 1296; but on this occasion the bishop of

Glasgow furnished from his own wardrobe the robes in which Bruce was

arrayed; he also presented to the new king a banner embroidered with the

arms of Baliol, which he had concealed in his treasury. A small circlet of

gold was placed by the bishop of St. Andrews on his head; and Robert the

Bruce, sitting in the state chair of the abbot of Scone, received the homage

of the few prelates and barons then assembled. The earl of Fife, as the

descendant of Macduff, possessed the hereditary right of crowning the kings

of Scotland. Duncan, the then earl, favoured the English interest, but his

sister Isabella, countess of Buchan, with singular boldness and enthusiasm,

repaired to Scone, and, asserting the privilege of her ancestors, a second

time crowned Bruce king of Scotland, two days after the former coronation

had taken place.

The

news of the murder of Comyn reached Edward while residing with his court at

Winchester, whither he had gone for the benefit of his health. He

immediately nominated the earl of Pembroke governor of Scotland, ordered a

new levy of troops, and, proceeding to London, held a solemn entertainment,

in which his eldest son, the prince of Wales, with three hundred youths of

the best families in England, received the honour of knighthood; and, with

the king, made a vow instantly to depart for Scotland, and take no rest till

the death of Comyn was avenged on Bruce, and a terrible punishment inflicted

on his adherents. The earl of Pembroke and Henry Percy having reached and

fortified Perth, Bruce, with his small band of followers, arrived in the

neighbourhood, and sent a challenge to Pembroke, whose sister was the widow

of the red Comyn, to come out and fight with him on the 18th of

June. Pembroke returned for answer that the day was too far spent, but that

he would meet him on the morrow. Satisfied with this assurance, Bruce

retreated to the wood of Methven, where his little army, towards the close

of the day, was unexpectedly attacked by Pembroke. Bruce made a brave

resistance, and after being four times unhorsed, was at last compelled, with

about four hundred followers, to retreat into the wilds of Athol. Here he

and his small band for some time led the life of outlaws. Having received

intelligence that his youngest brother Nigel had arrived with his queen at

Aberdeen, he proceeded there; and, on the advance of a superior body of the

English, conducted them in safety into the mountainous district of

Breadalbane. The adventures through which, at this period, the king and his

followers passed, and the perils and privations which they endured, are more

like the incidents of romance than the details of history. The lord of Lorn,

Alexander, chief of the Macdougalls, who had married the aunt of the red

Comyn, at the head of a thousand Highlanders, attacked the king at Dalry,

near the head of Loch Tay, in a narrow defile, where Bruce’s cavalry had not

room to act, and he was compelled to retreat, fighting to the last. At

Craigrostan, on the western side of Benlomond, is a cave, to which tradition

has assigned the honour of affording shelter to King Robert Bruce, and his

followers, after his defeat by Macdougall. Here, it is said, the Bruce

passed the night, surrounded by a flock of goats; and he was so much pleased

with his nocturnal associates that he afterwards made a law that all goats

should be exempted from grassmail or rent. Finding his cause becoming every

day more desperate, he sent the queen and her ladies to Kildrummie castle,

under the charge of Nigel Bruce and the earl of Athol; while he himself,

with his remaining followers, amounting now only to about two hundred,

resolved to force a passage to Kintyre, and escape from thence into the

northern parts of Ireland. On arriving at the banks of Loch Lomond, there

appeared no mode of conveyance across the loch. After much search, Sir James

Douglas discovered in a creek a crazy little boat, by which they safely got

across.

While engaged in the chase, a resource to which they were driven for food,

Bruce and his party accidentally met with Malcolm earl of Lennox, a staunch

adherent of the king, who, pursued by the English, had also taken refuge

there. By his exertions the royal party were amply supplied with provisions,

and enabled to reach in safety the castle of Dunaverty in Kintyre, where

they were hospitably received by Angus of Isla, the lord of Kintyre. After a

stay of three days the king embarked with a few of his most faithful

adherents, and, after weathering a dreadful storm, landed at the little

island of Rachrine, about four miles distant from the north coast of

Ireland. On this small island he remained during the winter.

In

his absence the English monarch proceeded with unrelenting cruelty against

his adherents in Scotland. Nigel Bruce, with those chiefs who had aided him

in the defence of Kildrummie castle, which they were compelled to surrender,

were hurried in chains to Berwick, and immediately hanged. Many others of

noble rank shared a similar fate. Even the female friends of Bruce did not

escape King Edward’s fury. The queen, her daughter Marjory, and their

attendants, having taken refuge in the sanctuary of St. Duthac, in

Ross-shire, were sacrilegiously seized by the earl of Ross, and committed to

an English prison. The two sisters of Bruce were also imprisoned. The

countess of Buchan was suspended in a cage of wood and iron from one of the

outer turrets of the castle of Berwick, in which she remained for four

years.

Bruce’s estates, both in England and Scotland, were confiscated, and he

himself and all his adherents were solemnly excommunicated by the Pope’s

legate at Carlisle. Of these dire national and personal misfortunes, the

king, in his island retreat, was happily ignorant; and he had so effectually

concealed himself, that it was generally believed that he was dead. On the

approach of spring, 1307, Bruce resolved to make one more effort for the

recovery of his rights. He set sail for the island of Arran, with

thirty-three galleys and three hundred men. He next made a descent upon

Carrick; and, surprising at midnight the English troops in his own castle of

Turnberry, then held by the Lord Henry Percy, he put nearly the whole

garrison to the sword. He now ravaged the neighbouring country, and levied

the rents of his hereditary lands, while many of his vassals flocked to his

standard.

Meantime, an English force of a thousand strong being raised in

Northumberland, advanced into Ayrshire, and, unable to oppose it, Bruce

retired into the mountainous districts of Carrick. Percy soon after

evacuated Turnberry castle, and returned to England. This success was

counter-balanced by the miscarriage of the king’s brothers, Thomas and

Alexander Bruce, who, with seven hundred men, attempting a descent at Loch

Ryan, in Galloway, were attacked by Duncan Macdowall, a Celtic chief, and

almost all cut to pieces. The two brothers being taken prisoners, were

conveyed to Carlisle and executed.

While English reinforcements continued to pour into Scotland from all

quarters, Bruce, shut up in the fastnesses of Carrick, found himself with

only sixty men, the remainder having deserted him in the belief that his

cause was hopeless. Beset on every side by the English, he was also exposed

to danger from private treachery; and his escapes were often almost

miraculous. Among the most inveterate of his foes were the men of Galloway,

who, hoping to effect his destruction and that of all his followers,