|

BROUN,

or BROWN, a surname common in Scotland, as Browne is in England and

Ireland, the same as Brun or Brune in France, In its first

form there is an ancient family, the Brouns of Colstoun, in the county of

Haddington, a younger branch of which enjoys a baronetcy, and according to

tradition, was founded soon after the Conquest, by a French warrior, bearing

the arms of the then royal family of France, with which he claimed alliance.

In the roll of Battle Abbey there is a knight named Brone among the Norman

adventurers who accompanied William the Conqueror into England, but whether

this be the ancestor of any of the innumerable families of the name of Brown

in this country, it is impossible to say. The name, doubtless, in ancient

times was bestowed, in some instances, from the colour or complexion of

those who adopted it as a surname.

Early in the

twelfth century one Walterus le Brun is found flourishing in Scotland. He

was one of the barons who witnessed the inquisition of the possessions of

the church of Glasgow made by Earl David in 1116, in the reign of his

brother, Alexander the First.

Sir David le

Brun was one of the witnesses, with King David the First, in laying the

foundation of the abbey of Holyroodhouse, 13th May 1128.

‘A thowsand a hundyr and twenty yhere,

And awcht to that, to rekyne clere,

Foundyd wes the Halyrwd hows,

Fra thine to be relygyows.’

Wyntoun.

He devised to that

abbacy “lands and acres in territories de Colstoun,” for prayers to be said

for “the soul of Alexander and the health of his son.” Thomas de Broun is

witness in a charter by Roger de Moubray to the predecessor of the lairds of

Moncrieff, in the time of King Alexander the Second.

The name of Ralph

de Broun appears in the Ragman Roll as that of one of the barons of Scotland

who swore fealty to Edward the First at Berwick, in 1296.

Richard de Broun,

keeper of the king’s peace in Cumberland, was forfeited in the Black

parliament in 1320.. He is styled an esquire, and was beheaded, with Sir

David de Brechin and two other knights, Sir Gilbert de Malherbe and Sir John

Logie, for being concerned in the conspiracy of de Soulis that year. (See

BRECHIN, lord of, ante.)

From King David

the Second, the family of Colstoun received a charter, “Johanni Broun filio

David Broun de Colstoun.”

William Broun,

baron of Colstoun, in the reign of James the First married Margaret de

Annand, co-heiress of the barony of Sauchie, descended from the ancient

lords of Annandale.

Sir William Broun

of Colston, warden of the west marches, commanded a party of Scots in a

battle fought on what was anciently a moor in the parish of Dornock,

Dumfries-shire, against a party of English, led by Sir Marmaduke Langdale

and Lord Crosby, when the English were defeated, and both their commanders

slain. So sanguinary was the conflict that, according to tradition, a

spring-well on the spot, still called Sword well, ran blood for three days.

Towards the end of

the fifteenth century William Broun of Colstoun was lord director of the

court of chancery in Scotland.

With other

Haddingtonshire barons, the Brouns of Colstoun appear to have favoured the

Homes, as on April 6, 1529, precepts of remission were granted to Mr.

William Broun, tutor of Colstoun, and four others, and to George Fawside of

that ilk, for their treasonably assisting George, Lord Home and the deceased

David Home of Wedderburn, his brothers and accomplices, being the king’s

rebels and at his horn.

George Broun of

Colstoun, who lived in the beginning of the seventeenth century, married

Jean Hay, second daughter of Lord Yester, ancestor of the Marquis of

Tweeddale. The dowry of this lady consisted of the famous “Colstoun pear,”

which Hugo de Gifford of Yester, her remote ancestor, famed for his

necromantic powers, described in Marmion, and who died in 1267, was supposed

to have invested with the extraordinary virtue of conferring unfailing

prosperity on the family which possessed it. Lord Yester, in giving away his

daughter, is said to have informed his son-in-law that good as the lass

might be her dowry was much better, because while she could only have value

in her own generation, the pear, so long as it continued in the family,

would cause it to flourish to the end of time. Accordingly, the pear has

been carefully preserved in a silver box, as a sacred palladium. About the

seventeenth century, the lady of one of the lairds of Colstoun, on becoming

pregnant, felt a longing for the forbidden fruit, and took a bite of it.

Another version of the story says that it was a maiden lady of the family

who, out of curiosity chose to try her teeth upon it. Very soon after, two

of the best farms on the estate were lost in some litigation, while the pear

itself straightway became stone-hard, and so remains to this day, with the

marks of the lady’s teeth indelibly imprinted on it. The origin of this

wondrous pear is, by another tradition, said to have been thus: – One of the

ancestors of the Colstoun family married a daughter of the above-named Hugo

of Yester, the renowned warlock of Gifford, and as the bridal party were

proceeding to the church, the wizard lord stopped beneath a pear tree, and

plucking one of the pears, handed it to his daughter, telling her that he

had no dowry to give her, but that as long as that gift was kept. good

fortune would never desert her or her descendants. Apart from the

superstition attached to it, this curious heirloom is certainly a most

wonderful vegetable curiosity, having existed for nearly six centuries.

George Broun,

baron of Colstoun, in the reign of Charles the First, married a daughter of

Sir David Murray of Stanhope, and had, with a younger son, George (ancestor

of the present baronet of Colstoun) to whom he granted by charter the barony

of Thornydyke, in Berwickshire, an elder son, Sir Patrick Broun of Colstoun,

who, in consequence of his eminent services and the fidelity of the ancient

family he represented, was created a knight and baronet of Nova Scotia, 16th

February 1686, with remainder of the title to his heirs male for ever. Sir

George Broun, the second baronet, his son, married a daughter of the first

earl of Cromarty, and died in 1718; leaving an only daughter, who inherited

the estate, while the baronetcy went to the heir male. The family thus

became split betwixt the heirs male and the heirs of line, the title

devolving upon the Thornydyke branch and the estates upon an heiress, who

married George Broun of Eastfield, from whom descended George Broun of

Colstoun judicially styled Lord Colstoun, who became a lord of session in

1756 and died in 1776; and the late Christian, countess of Dalhousie, only

child and heiress of Charles Broun, Esq. of Colstoun, and died 22d February

1839. The present marquis of Dalhousie (James Andrew Broun-Ramsay) in right

of his mother, is the representative of the elder branch.

Sir George Broun,

son of Alexander Broun of Thornydyke castle and Bassendean, Berwickshire,

and of a lady of the ancient house of Swinton of Swinton, succeeded his

cousin as third baronet, and dying without male issue, his brother, Sir

Alexander, became fourth baronet. He married Beatrice, daughter of Alexander

Swinton, Lord Meringston, and died in 1750. His son, Sir Alexander, fifth

baronet, having died in 1775, without male issue, the baronetcy devolved

upon his cousin, the Rev. Sir Alexander Broun, minister of Lochmaben, who

declined to take up the title. He married Robina, daughter of Colonel Hugh

M’Bride of Beadland, Ayrshire, and died in 1782. With several daughters he

had two sons, viz., James, who, in 1825, revived the title, and William, of

Newmains, who married and settled in the island of Guernsey, where his

descendants are still to be found.

Sir James, the

seventh baronet, left a family of four sons and two daughters at his death,

30th Nov. 1844. His eldest son, Sir Richard Broun, eighth

baronet, a knight commander of the order of St. John of Jerusalem, was

secretary of the Langue of that order in England, and also to the Committee

of Baronets for Privileges. He was also secretary of the Central

Agricultural Society, and the author of various works on heraldry,

colonization, railway extension, &c. Born in 1801, he died unmarried in Dec.

1858. Before succeeding to the baronetcy he endeavoured to establish the

right of the eldest sons of baronets to the title of knight, and in 1842

assumed the title of “Sir.” His brother Sir William, a solicitor in

Dumfries, became ninth baronet.

BROWN, JAMES,

an eminent linguist and traveller, the son of James Brown, M.D., was born at

Kelso, in the county fo Roxburgh, May 23, 1709. He was educated under the

Rev. Dr. Robert Friend at Westminster School, where he was well instructed

in the classics. In the end of 1722 he went with his father to

Constantinople; and having a great natural aptitude for the acquirement of

languages, he obtained a thorough knowledge of the Turkish and Italian, as

well as the modern Greek. In 1725 he returned home, and made himself master

of the Spanish language. About the year 1732 he first started the idea of a

London Directory, or list of principal traders in the metropolis, with their

addresses. Having laid the foundation of this useful work, he gave it to Mr.

Henry Kent, a printer in Finch Lane, Cornhill, who, continuing it yearly,

made a fortune by it.

In July 1741 he

entered into an agreement with twenty-four of the principal merchants of

London, members of the Russian Company, of which Sir John Thompson was then

governor, to go to Persia, to carry on a trade through Russia, as their

chief agent or factor. On 29th September of the same year he

sailed for Riga; whence he passed through Russia, and proceeding down the

Volga to Astracan, voyaged along the Caspian Sea to Reshd in Persia, where

he established a factory. He continued in that country nearly four years;

and, upon one occasion, went in state to the camp of Nadir Shah, better

known by the name of Kouli Khan, to deliver a letter to that chief from

George the Second. While he resided in Persia, he applied himself to the

study of the Persian language, and made such proficiency in it, that, after

his return home, he compiled a very copious Persian Dictionary and Grammar,

with many curious specimens of the Persian mode of writing, which he left

behind him in manuscript.

Dissatisfied with

the conduct of the Russian Company in London, and sensible of the dangers to

which the factory was constantly exposed frm the unsettled and tyrannical

nature of the Persian government, he resigned his charge, and returned to

England on Christmas-day 1746. In the following year the factory was

plundered of property to the amount of eighty thousand pounds sterling,

which led to a final termination of the Persian trade. The writer of his

obituary in the ‘Gentleman’s Magazine’ for December 1788, says, that he

possessed the strictest integrity, unaffected piety, and exalted but

unostentatious benevolence, with an even, placid, and cheerful temper. In

May 1787 he was visited with a slight paralytic stroke, but soon recovered

his wonted health and vigour. Four days before his death, he was attacked by

a much severer stroke, which deprived him, by degrees, of all his faculties,

and he expired without a groan, November 30, 1788, at his house at Stoke

Newington, Middlesex. Mr. Lysons, in his ‘Environs,’ vol. iii., states, that

Mr. Brown’s father, who died in 1733, published anonymously a translation of

two ‘Orations of Isocrates.’

BROWN, JOHN,

author of the ‘Self-Interpreting Bible,’ the son of a weaver, was born in

1722, in the small village of Carpow, county of Perth. His parents dying

before he was twelve years of age, it was with some difficulty that he

acquired his education. “I was left,” he says, “a poor orphan, and had

nothing to depend on but the providence of God.” He was but a very limited

time at school. “One month,” he says himself, “without his parents’

allowance, he bestowed upon Latin.” Nevertheless, by his own intense

application to study, before he was twenty years of age, he had obtained an

intimate knowledge of the Latin, Greek, and Hebrew languages, with the last

of which he was critically conversant. He was also acquainted with the

French, Italian, German, Arabic, Persian, Syriac, and Ethiopic. His great

acquisition of knowledge, without the assistance of a teacher, appeared so

wonderful to the ignorant country people, that a report was circulated far

and wide that young Brown had acquired his learning in a sinful way, that

is, by intercourse with Satan! In early youth he was employed as a shepherd.

He afterwards undertook the occupation of pedlar or travelling merchant. In

1747 he established himself in a school at Gairney Bridge, in the

neighbourhood of Kinross, a place celebrated as the spot where the Associate

Presbytery was first constituted. The same school was afterwards taught by

Michael Bruce the poet. Here Brown remained two years. He subsequently

taught for a year and a half another school at Spital, near Linton. Having

attached himself to the body who, in 1733, seceded from the Church of

Scotland, in 1748 he entered on the regular study of philosophy and divinity

in connection with the Associate Synod. In 1750 he was licensed to preach

the gospel by the Associate Presbytery of Edinburgh, at Dalkeith; and soon

after received a call from the Secession congregation at Stow, also one

nearly at the same time from Haddington. He chose the latter, and was

ordained pastor of the Haddington congregation 4th July 1751. In

1758 he published an ‘Essay towards an Easy Explication of the Catechisms,’

intended for the use of the young; and in 1765 his ‘Christian Journal,’ once

the most popular of all his works. In 1768 he was elected professor of

divinity under the Associate Synod. This situation he held for twenty years.

His ‘Self-Interpreting Bible,’ by which his name is best known, appeared in

two quarto volumes in 1778. Of this popular and useful work numerous

stereotyped editions have appeared both in Scotland and England, each having

very extensive circulation, and each successively improved in form or

arrangement. A recent one, with the additions of his grandson, J. B.

Patterson, surpasses all previous ones in form, type, and illustrations. His

piety and learning, and fame as an author, made his name extensively known,

not only in Scotland, but in England and America, and in 1784 he received a

pressing invitation from the Reformed Dutch Church in New York, to be their

tutor in divinity, which he declined. He died at Haddington June 19, 1787.

He was twice married, and had six sons and one daughter. The sons were: 1.

John, for many years Burgher minister at Whitburn, Linlithgowshire, a memoir

of whom is given below. 2. Ebenezer, Burgher minister at Inverkeithing,

whose apostolic look and person and mode of preaching, are mentioned as most

remarkable. 3. Thomas Brown, D.D., Burgher minister at Dalkeith, and author

of an octavo volume of sermons. 4. Samuel, merchant, Haddington, the founder

of itinerating libraries. He was the father of Dr. Samuel Brown, and eminent

chemist, who died young in 1856. 5. David, bookseller in Edinburgh. 6. Dr.

William Brown, of Duddingstone, long the secretary of the Scottish

Missionary Society, and the author of a ‘History of Missions,’ and of a

memoir of his father. The only daughter, Mrs. Patterson, was the mother of

two sons and a daughter. The elder son, the Rev. John Brown Patterson,

minister of Falkirk, styled by Lord Cockburn “Athenian Patterson,” died in

his early prime. He was the author of the memoir of his grandfather,

prefixed to Fullarton’s edition of his ‘Self-Interpreting Bible.’ The

younger son, Alexander Simpson Patterson, D.D., minister of Free

Hutchesontown Church, Glasgow, and the author of several theological works,

is editor of an edition published in 1858, of his brother’s fine

characteristic posthumous work on our Lord’s Farewell Discourse.

Mr. Brown’s

principal works are:

A Dictionary of

the Holy Bible, on the plan of Calmet, but chiefly adapted to common

readers. 2 vols. 8vo, Edin. 1769.

A General History

of the Christian Church; (a very useful compendium of church history, partly

on the plan of Mosheim, or perhaps, rather, of Lampe.) 2 vols. 12mo. Edin.

1771.

The

Self-Interpreting Bible. (This edition of the Bible is so called from its

marginal references, which are far more copious than in any other edition.

It has been frequently reprinted.) 2 vols. 4to, Edin. 1778.

A Compendious View

of Natural and Revealed Religion, in seven books. 8vo, Glasgow, 1782.

Harmony of

Scripture Prophecies, and History of their fulfilment. 8vo, Glasgow, 1784.

A Compendious

History of the British Churches. 2 vols. 12mo, 1784.

His other

publications are as follows:

A Help for the

Ignorant, being an Essay towards an Easy Explication of the Assembly’s

Shorter Catechism. 12mo, Edin. 1758.

A Brief

Dissertation on Christ’s Righteousness, showing to what extent it is imputed

to us in Justification. 12mo. Edin. 1759.

Two Short

Catechisms mutually connected; the questions of the former being generally

supposed and omitted in the latter. 12mo, Edin. 1764.

The Christian

Journal, or common incidents, spiritual instructors. 12mo, Edin. 1765.

A Historical

account of the Secession from the Church of Scotland. 8vo, Edin. 1766.

Eighth edition, 1802.

Letters on the

Constitution, Discipline, and Government of the Christian Church. 12mo,

Edin. 1767.

Sacred Tropology,

or a brief view of the figures and explanation of the metaphors contained in

Scripture. 12mo, Edin. 1768.

Religious

Steadfastness Recommended. A Sermon. 12mo, Edin. 1769.

The Psalms of

David in Metre, with notes exhibiting the connection, explaining the sense,

and for directing and animating the devotion. 12mo, Edin. 1775.

The Oracles of

Christ, and the Abominations of Antichrist, contrasted. 12mo, Glasgow, 1778.

The absurdity and

perfidy of all authoritative toleration of gross heresy, blasphemy,

idolatry, and popery in Britain. 12mo, Glasgow, 1780.

The fearful shame

and contempt of mere professed Christians, who neglect to raise up spiritual

children to Jesus Christ. Two Sermons. 12mo, Glasgow, 1780.

An Evangelical and

Practical View of the types and figures of the Old Testament dispensation.

12mo, Glasgow, 1781.

The Christian, the

Student, and the Pastor, exemplified in the lives of nine eminent ministers.

Edin. 1782.

The Young

Christian exemplified. 12mo, Glasgow, 1782.

The Necessity and

Advantage of Earnest Prayer for the Lord’s special direction in the choice

of pastors; with an appendix of free thoughts concerning the transportation

of ministers. Edin. 1783.

A Brief

Concordance to the Holy Scriptures. 18mo, Edin. 1783.

Practical Piety

exemplified in the lives of thirteen eminent Christians. 12mo, Glasgow,

1783.

Thoughts on the

Travelling of the Mail on the Lord’s Day. 12mo, 1785.

The Re-Exhibition

of the Testimony defended. 8vo, Glasgow.

Devout Breathings

of a Pious Soul; with additions and improvements. Edin.

The necessity,

seriousness, and sweetness of Practical Religion, in an awakening call, by

Samuel Corbyn; with four solemn addresses to sinners, young and old.

The following were

published after his death:

Select Remains:

with some account of his life. 12mo, London, 1789.

Posthumous Works.

12mo, Perth, 1797.

An Apology for a

more frequent administration of the Lord’s Supper; with answers to

objections. 12mo, Edin, 1804.

BROWN, JOHN,

a pious and useful divine, eldest son of the preceding, by his first wife,

Janet Thomson, daughter of Mr. John Thomson, merchant, Musselburgh, was born

at Haddington, 24th July, 1754. From his youth he gave decided

indications of piety. He was sent to the university of Edinburgh, when he

was scarcely fourteen years of age, and about the year 1772 he entered on

the study of divinity, under the superintendence of his father. He was

licensed to preach the gospel by the Associate presbytery of Burghers at

Edinburgh, 21st May 1776. Soon after, he received a call from the

Burgher congregation of Whitburn, Linlithgowshire, and was ordained to that

charge, 22d May 1777. During a long career of ministerial usefulness, he

maintained a high degree of popularity, his preaching being characterized by

the simplicity and seriousness of his manner, and by the highly evangelical

tone of his sentiments. He exerted himself in promoting the various

religious institutions of the day, and took a deep interest especially in

the spiritual improvement of the Highlanders of Perthshire.

When his strength

began to decline, his people gave a call to Mr. William Millar, to be his

colleague and successor, and he was accordingly ordained as such 15th

November 1831. After the ordination, Mr. Brown preached only eight Sabbaths.

He was seized with a severe paralytic attack, and after lingering for a few

weeks, he died 10th February 1832, in the 78th year of

his age, and 56th of his ministry.

Mr. Brown’s chief

works are:

Gospel Truth

accurately stated and illustrated by the Reb. Messrs. Hog, Boston, Erskines,

and others, occasioned by the republication of the marrow of Modern

Divinity. 12mo, 1817. New and greatly enlarged edition. Glasg. 1831.

Notes, Devotional

and Explanatory, on the Translations and Paraphrases generally used in the

Presbyterian Congregations in Scotland. Published with an edition of the

Psalms with his father’s notes, in Glasgow.

Memorials of the

Nonconformist Ministers of the Seventeenth Century, with an Introductory

Essay by William M’Gavin, Esq. Glasg. 1832. (This was the last literary work

of both the excellent men whose names appear on the title-page. Mr. Brown

died just before it went to press, and Mr. M’Gavin just as it was leaving

it.)

His other minor

works are:

Memoirs of the

Life and Character of the late Rev. James Hervey, A.M. 1806. Three editions.

A brief Account of

a Tour in the Highlands of Perthshire. 12mo, 1815. Memoirs of Private

Christians.

Christian

Experience; or the Spiritual Exercise of Eminent Christians in different

ages and places, stated in their own words. 18mo. 1825.

Descriptive List

of religious books in the English language fit for general use. 12mo, 1827.

Memoir of the Rev.

Thomas Bradbury. 18mo, 1831.

He also edited the

following:

The Evangelical

Preacher. a Select Collection of doctrinal and practical Sermons, chiefly of

English divines of the 18th century. 3 vols. 12mo, 1802-1806.

A Collection of

Religious Letters from books and MSS. 12mo. 1813.

A Collection of

Letters from printed books and MSS., suited to Children and Youth. 18mo.

1815.

Evangelical

Beauties of the late Rev. Hugh Binning, with an account of his Life. 32mo,

1828.

Evangelical

Beauties of Archbishop Leighton, 12mo. 1829.

After the death of

Mr. Brown, were published Letters on Sanctification, some of which had

previously appeared in the Christian Repository and Monitor, with a Memoir

of his Life by his son-in-law, the Rev. David Smith of Biggar.

BROWN, JOHN, D.D.,

an eminent divine, the son of the subject of the preceding memoir, was born

July 12, 1784, at the house of Burnhead, in the parish of Whitburn,

Linlithgowshire. Having, from early life, chosen the ministry as a

profession, in November 1797, he entered the university of Edinburgh, where

he studied for three sessions. In April 1800, when scarcely sixteen years of

age, he went to Elie, Fifeshire, as a teacher. In the following August, he

was examined by the Associate presbytery of Perth at Newburgh, and

subsequently entered the divinity hall of that body at Selkirk, under Dr.

George Lawson, who had succeeded his grandfather, in 1787, as professor of

divinity to the Secession church.

While pursuing his

studies for the ministry, Mr. Brown became, in April 1803, a private teacher

in Glasgow, and in February 1805 he was licensed at Falkirk to preach the

gospel by the Burgher presbytery of Stirling and Falkirk. He had very soon

calls to both Stirling and Biggar, and in September 1805, was appointed to

the latter place. In October of the same year he proceeded to London for

three months, to supply the pulpit of Dr. Waugh, Wells Street, one of the

originators of the London Missionary Society.

Mr. Brown was

ordained Burgher minister at Biggar, February 6, 1806. In 1817 he received a

call to become the minister of the Burgher church at North Leith but the

Associate Synod would not consent, at that time, to his removal from Biggar.

On the

translation, in 1821, of the Rev. Dr. James Hall from Rose Street chapel,

Edinburgh, which had been built for him, to a larger place of worship, also

erected for him, in Broughton Place of that city, Mr. Brown received a call

from the Rose Street congregation to be his successor. This call he

accepted. On May 1, 1822, he was translated by deed of Synod to that

congregation, and on June 4, was admitted pastor of Rose Street church.

Dr. Hall died

November 28, 1826, and, on the following Sabbath, Dr. Brown preached his

funeral sermon in Broughton Place church. Subsequently he received a call

from the congregation, but was continued in his own charge by the synod at

their meeting in May 1828. Having received a second call, he was translated

by the Synod to Broughton Place church, in April 1829, and admitted 20th

May following. On the institution of the professorship of Exegetical

Theology by the United Secession Synod in 1834, he was, in April that year,

appointed to that chair, which had been reorganized according to a plan of

which he was the author, and in which the fundamental importance of this

study, which has since impressed itself on all Scottish churches, was for

the first time recognised.

In the

religio-political controversies of the period, Dr. Brown not unfrequently

found himself involved, from his fervour in the cause of what he conceived

to be the truth. The first of these was on what was then called the

Apocrypha question. This controversy arose in consequence of the British and

Foreign Bible Society having permitted the Apocrypha to be inserted in the

Bible, and ultimately hinged upon its sincerity in professing to reject it

from their editions of that work. Dr. Andrew Thomson, minister of St.

George’s, Edinburgh stood forth as the assailant of the Society, his

principal opponents being Drs. Grey and Brown, and his chief supporter,

Robert Haldane.

The question as to

the lawfulness and expediency of the existing connexion between church and

State was the next. It was not a new one, but it now assumed a bolder and

more conspicuous aspect than it had ever before held, and excited an

extraordinary degree of ferment in the public mind, in consequence of an

attack made upon its lawfulness on more exclusively scripture grounds, by a

leading member of Dr. Brown’s denomination, Dr. Andrew Marshall, in a Sermon

published in May 1829. In this controversy Dr. Brown took a prominent and

consistent part. A voluntary church association having been formed in

Edinburgh, (Dr. Brown being one of the committee,) led, in February 1833, to

the formation of an association at Glasgow for promoting the interests of

the Church of Scotland, and thenceforth “the battle of Establishments” waxed

hotter and hotter. Voluntary church associations and Church Defence

associations were formed over the whole kingdom, and for several years

after, churchmen and dissenters no longer acted together as brethren, either

in religious societies or in the social intercourse of private life.

A more painful and

trying ordeal awaited Dr. Brown. In 1842, four ministers of Dr. Brown’s

denomination were expelled from the Synod, for holding views subversive of

the special reference of the atonement as held by their body. At the meeting

of Synod in October 1843, in consequence of the transmission of an overture

by the Presbytery of Paisley, the Synod requested the two senior professors,

Drs. Balmer and Brown, to express their sentiments on the doctrinal points,

regarding which differences from the views of the body were alleged to be

held by these ministers. This the professors accordingly did, much to the

satisfaction, with the conference that followed, of the Synod, as stated in

their finding on the occasion. Subsequently Dr. Marshall published a

pamphlet entitled ‘The Catholic Doctrine of Redemption Vindicated,’ in the

Appendix to which he threw out certain imputations against Drs. Brown and

Balmer, of which they complained to the Synod. A committee was appointed to

take Dr. Marshall’s statements into consideration, and also the published

speeches of the two professors. The result was that Dr. Marshall disavowed

the insinuation that they taught anything inconsistent with the standards of

the church, and he spontaneously intimated his purpose to suppress the

Appendix altogether. But the matter did not end here, as it was thought it

would, for Dr. Marshall returned to the charge.

At the meeting of

the Synod in May 1845, Dr. Brown, by the advice of his presbytery, presented

a complaint in reference to a pamphlet published, shortly before, by Dr.

Marshall, entitled, ‘Remarks on the Statements on certain doctrinal points

made before the United Secession Synod at their request by the two senior

Professors,’ in which he pronounced the doctrine enunciated by them to be

“subverting the very foundation of our hopes, entirely subverting the

doctrine of election, rendering the gospel little more than a solemn

mockery,” with more to the same effect; and he requested that the Synod

would either enter on the investigation of these charges “in due form,” or

release him from his professorial duties. The Synod, after finding that Dr.

Brown had acted with great propriety in bringing the matter before them,

expressed their satisfaction with the explanation which he had given in his

‘Statement’ and other wise, declaring also their entire confidence in his

soundness in the faith, and their trust that he would continue to discharge

his important functions with equal honour to himself and benefit to the

church. In regard to Dr. Marshall, they found that in his recently published

pamphlet he had reiterated serious charges, formerly brought forward on

insufficient grounds against Dr. Brown, in a still more offensive form, that

he ought to have brought the matter before the church courts in the only

competent way, and that he should therefore, be admonished at the bar of the

Synod. After this decision, Dr. Marshall intimated his intention of

bringing a libel against Dr. Brown, and another meeting of Synod was

appointed in July, that he might have the opportunity of producing his libel

before the next meeting of the Divinity Hall.

Accordingly, in

the following July, Dr. Marshall, assisted by Dr. Hay of Kinross, presented

a libel against Dr. Brown, being the first prosecution for heresy by libel

that had ever taken place in the Synod of the Secession church. The libel

contained five counts, and Dr. Brown was triumphantly acquitted on them all.

On the whole case the Synod unanimously adopted the following finding:

“The Synod finds

that there exists no ground even for suspicion that he holds, or has ever

held, any opinion on the points under review inconsistent with the Word of

God, or the subordinate standards of this church. The Synod, therefore,

dismisses the libel; and while it sincerely sympathizes with Dr. Brown in

the unpleasant and painful circumstances in which he has been placed, it

renews the expression of confidence in him given at last meeting, and

entertains the hope that the issue of this cause has been such as will, by

the blessing of God, restore peace and confidence throughout the church, and

terminate the unhappy controversy which has so long agitated it.”

During the whole

discussions in this unhappy case, Dr. Brown displayed great wisdom and

Christian temper, and his own congregation sympathized with him most

sincerely in the trying and painful circumstances in which he had been

placed. As a mark of their affection and sympathy, they met in the following

September, and presented him with a valuable testimonial.

One the death of

dr. Peddie, senior pastor of Bristo Street congregation, Edinburgh, 11th

October, 1845, Dr. Brown preached his funeral sermon to his congregation,

which was afterwards printed. In the movement for the union of the Secession

and Relief bodies, he took a warm part. After that work had been

accomplished, and the United Presbyterian Church formed in 1847, he devoted

his remaining efforts to expository comments on the Sacred Scriptures.

The duties of his

professorship Dr. Brown discharged with much enthusiasm and assiduity till

1857, when increasing infirmities rendered him unequal to the labours which

it imposed. His pulpit ministrations he was also compelled to relinquish at

the same time, but occasionally, when his health permitted, he would appear

in public to cheer and instruct his flock.

For some time he

suffered severely from internal pains, and it was supposed that his liver

was affected, but latterly he enjoyed a complete immunity from these. His

personal appearance, which was fine and dignified, was, previously to his

death, greatly changed, in reference to which he himself expressively said,”

The Master changes our countenance, and sends us away.”

Dr. Brown died at

his house, Arthur Lodge, Newington, Edinburgh, 13th October 1858,

in his 74th year. so high was the estimation in which he was

held, that he may be said to have had a public funeral. The Lord Provost and

magistrates of Edinburgh attended in their official robes. He was followed

to the grave, in the Lower Calton burying-ground, by his former

congregations of Biggar and Rose Street, as well as by his people of

Broughton Place church, and by ministers of all denominations. All felt that

a good man and “a prince in Israel” had been gathered to his rest. On the

Sunday succeeding his funeral, his colleague, Dr. Andrew Thomson, and Dr.

Harper, North Leith, preached funeral sermons in Broughton Place church. He

was twice married, first, to Jane Nimmo, daughter and sister of two eminent

physicians in Glasgow. she died in 1816; and, secondly, to Margaret Fisher

Crum, of the Thornliebank family, descended from Ebenezer Erskine and Mr.

Fisher, two of the five fathers of the Secession. He left three sons and as

many daughters. Two of his sons were educated for the medical profession;

Dr. John Brown of Edinburgh, and Dr. William Brown. The third son was but a

youth at the time of his father’s death.

The influence of

Dr. Brown in his own denomination was very great. But he was never an

ecclesiastical leader. in the generally understood sense of the term. He had

little turn for the platform, and he spoke but rarely in church courts. In

all public questions, however, he took a deep and enlightened interest, and

when he did express his opinions on any subject, it was with an authority

which showed that h had thoroughly considered it, and was familiar with all

its bearings. Both as a preacher and a lecturer, he was an evangelical of

the highest order, closely resembling the founders of his denomination in a

religious aspect, vigorous, pure, fervent, manly, and profoundly pathetic.

Deemed the ripest

Biblical scholar of his age, it was only late in life that he became a

theological writer. He had a magnificent library, probably the largest

clerical library in Scotland, except one. His Greek New Testaments, which he

commenced to hoard when he was fourteen, were, it is believed, unique in

number and in quality for a private library, and his Latin and French

theological authors, of the 16th century, were all but complete.

He had also a fine collection of classics, which he read to the last.

although he taught as a professor for a quarter of a century, his series of

commentaries, on which his name must chiefly rest, were published within the

last ten years of his life. The publication of more than ten octavo volumes

by a man considerably above sixty when he began, and several of these on

some of the most difficult Epistles of the New Testament, is certainly

something unusual in the history of literature.

Dr. Brown’s more

important works are:

Expository

Discourses on the First Epistle of the Apostle Peter. In three volumes. 8vo.

Discourses and

Sayings of our Lord Jesus Christ: Illustrated in a Series of Expositions. In

three volumes. Second edition; 8vo.

An Exposition of

our Lord’s Intercessory Prayer, with a Discourse on the Relation of our

Lord’s Intercession to the Conversion of the World. 8vo.

Sufferings and

Glories of the Messiah signified beforehand to David and Isaiah; An

Exposition of Psalm xviii. and Isaiah lii. 13; liii. 12. 8vo.

An Exposition of

the Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Galatians. 8vo.

He also published

the following as separate Sermons:

The Danger of

Opposing Christianity, and the Certainty of its final Triumph: A Sermon

preached before the Edinburgh Missionary Society, on Tuesday, 2d April,

1816. 8vo.

On the State of

Scotland, in reference to the Means of Religious Instruction: A Sermon

preached at the Opening of the Associate Synod, on Tuesday, 27th

April, 1819. 8vo.

On the Duty of

Pecuniary Contribution of Religious Purposes: A Sermon preached before the

London Missionary Society, on Thursday, May 10, 1821. Third edition. 18mo.

Sermon occasioned

by the Death of the Rev. James Hall, D.D., Edinburgh. 8vo. 1826.

The Abolition of

Death: a Sermon. Foolscap 8vo.

The Friendship of

Christ and his People Indissoluble: A Sermon on the Death of the Rev. John

Mitchell, D.D., Glasgow. 8vo.

Human Authority in

Religion condemned by Jesus Christ: An Expository Discourse. Foolscap 8vo.

The Christian

Ministry, and the Character and Destiny of its Occupants, Worthy and

Unworthy: A Sermon on the Death of the Rev. Robert Balmer, D.D., Berwick.

Second edition. 8vo.

Heaven: A Sermon

on the Death of the Rev. James Peddie, D.D., Edinburgh. 8vo.

The Present

Condition of them who are “Asleep in Christ:” A Sermon on the Death of the

Rev. Hugh Heugh, D.D., Glasgow. 8vo.

The Good Shepherd:

A Sermon. 24mo.

His smaller tracts

are as follows:

1. On the Bible

Society controversy.

Statement of the

Claims of the British and Foreign Bible Society on the Support of the

Christian Public: With an Appendix. 8vo.

Remarks on Certain

Statements by Alex. Haldane, Esq., in his “Memoir of Robert Haldane of

Auchingray, and his brother, James A. Haldane.” 8vo.

2. On the

Voluntary controversy.

The Law of Christ

respecting Civil Obedience, especially in the Payment of Tribute; with an

Appendix of Notes; to which are added Two Addresses on the Voluntary Church

Controversy. Second edition, 1838. Third edition. 8vo.

What ought the

Dissenters of Scotland to do in the present Crisis? Second edition, 8vo.

1840.

3. On the

Atonement charge.

Opinions on Faith,

Divine Influence, Human Inability, the Design and Effect of the Death of

Christ, Assurance, and the Sonship of Christ. Second edition, with

additional Notes. 12mo.

Statement made,

April 1, 1845, before the United Associate Presbytery of Edinburgh, on

asking their Advice. Second edition. 12mo.

Miscellaneous.

Strictures on Mr.

Yates’ Vindication of Unitarianism. 8vo.

Remarks on the

Plans and Publications of Robert Owen, Esq. of New Lanark. 8vo.

On Forgetfulness

of God. Second edition. 18mo.

The Christian

Pastor’s Manual; a Selection of Tracts on the Duties, Difficulties, and

Encouragements of the Christian Ministry. 12mo.

A Tribute to the

Memory of a very dear Christian Friend. Third edition. 18mo.

Discourses suited

to the administration of the Lord’s Supper. Second edition. 12mo.

Hints on the

Permanent Obligation and Frequent Observance of the Lord’s Supper. Second

edition. 12mo.

Hints on the

Nature and Influence of Christian Hope. Post 8vo.

The Mourner’s

Friend; or, Instruction and Consolation for the Bereaved, a Selection of

Tracts and Hymns. Second edition. 32mo.

The United

Secession Church Vindicated from the Charge, made by James A. Haldane, Esq.,

of Sanctioning Indiscriminate Admission to Communion. 1839, 8vo.

On the Means and

Manifestations of a Genuine Revival of Religion: an Address delivered before

the United Associate Presbytery of Edinburgh, on November 19, 1839. Second

edition. 12mo.

Hints to Students

of Divinity; an Address at the Opening of the United Secession Theological

Seminary, August 3, 1841. Foolscap 8vo.

Memorial of Mrs.

Margaret Fisher Brown. Foolscap 8vo.

Statement on

certain Doctrinal Points; made October 5th, 1843, before the

United Associate Synod, at their request. 12mo.

On the Equity and

Benignity of the Divine Law. 24mo.

Comfortable Words

for Christian Parents Bereaved of Little Children. Second edition. 18mo.

Barnabas, or the

Christianly Good Man: in Three Discourses. Second edition. Foolscap 8vo.

Memorials of the

Rev. James Fisher, Minister of the Associate (Burgher) Congregation,

Glasgow; Professor of Divinity to the Associate (Burgher) Synod; and one of

the Four Leaders of the Secession from the Established Church of Scotland:

In a Narrative of his Life and a Selection from his Writings Foolscap 8vo.

Hints on the

Lord’s Supper and Thoughts for the Lord’s Table. Foolscap 8vo.

The Dead in

Christ, their State Present and Future, with Reflections on the Death of a

very deal Christian Friend. 18mo.

He also edited the

following works, viz.:

Maclaurin’s Essays

and Sermons, with an Introductory Essay. Second edition. 12mo.

Henry’s

Communicant’s Companion, with an Introductory Essay. Second edition. 12mo.

Venn’s Complete

Duty of Man, with an Introductory Essay. Second edition. 12mo.

Theological

Tracts. Selected and Original. 3 vols. Foolscap 8vo.

Letters of Dr John Brown

With Letters from Ruskin, Thackery and Others, Edited by his son and D. W.

Forrest, D.D. and with biographical Introductions by Elizabeth T. M'Laren

(1907)

BROWN, JOHN, M.D.

the founder of the Brunonian system of medicine, was born in 1735 or 1736,

either in the village of Lintlaws or that of Preston, parish of Buncle,

Berwickshire. His parents, who were Seceders, were in the humblest condition

of life, his father’s occupation not being above that of a day-labourer.

Nevertheless they were anxious to give their son a decent and religious

education. It was a frequent expression of his father’s, “that he would gird

his belt the tighter to give his son John a good education.” He early

discovered uncommon quickness of apprehension, and he was sent to school to

learn English much sooner than the usual period. Before he was five years of

age, he had read through almost the whole of the Old Testament. When he was

little more than five years of age, he had the misfortune to lose his

father. His mother afterwards married a weaver, by whose assistance he was

enabled to continue at school, where he was distinguished for his unwearied

application, his facility in mastering the tasks assigned to him, and the

retentiveness of his memory. Before he was ten years of age, he had gone

through the routine of grammar education required previously to entering

college. But as his mother could not afford to put him to the university, he

was bound apprentice to a weaver. For this occupation he had a rooted

aversion, and Mr. Cruickshank kindly offered to allow him to attend the

school gratuitously. He therefore resumed his studies, with the view of

ultimately becoming a preacher of the Secession. In a short time he became

so necessary to his master, that he was occasionally deputed to instruct the

younger scholars.

At this period, we

are told, “he was of a religious turn, and was so strongly attached to the

sect of Seceders, or Whigs, as they are called in Scotland, in which he had

been bred, that he would have thought his salvation hazarded, if he had

attended the meetings of the established church. He aspired to be a preacher

of a purer religion.” A circumstance which happened abut his thirteenth year

had the effect of making him altogether relinquish the idea of becoming a

seceding minister. Having been persuaded, by some of his school-fellows, to

hear a sermon in the parish church of Dunse, he was in consequence summoned

to appear before the session of the congregation of Seceders to which he

belonged, to be rebuked for his conduct, but his pride got the better of his

attachment to the sect. He resolved not to submit to the censure of the

session, and in order to avoid a formal expulsion, he at once renounced

their authority, and professed himself a member of the established church.

He afterwards acted for some years as usher in Dunse school; and about the

age of twenty, was engaged as tutor to the son of a gentleman in the

neighbourhood. This situation he left in 1755, when he went to Edinburgh,

where, while he studied at the philosophy classes, he supported himself by

instructing his fellow-students in the Greek and Latin languages. He

afterwards attended the divinity hall, and had proceeded so far in his

theological studies as to be called upon to deliver, in the public hall, a

discourse upon a prescribed portion of scripture, the usual step preliminary

to being licensed to preach.

About this time,

on the recommendation of a friend, he was employed by a gentleman then

studying medicine to translate into Latin An inaugural dissertation. The

superior manner in which he executed his task gained him great reputation,

which induced him to turn his attention towards the study of medicine.

Shortly afterwards he retired to Dunse, and resumed his former occupation of

usher. At Martinmas 1759 he returned to Edinburgh, and a vacancy happening

in one of the classes of the High School, he became a candidate, but without

success. Being unable to pay the fees for the medical classes, at the

commencement of the college session in that year, he addressed an elegantly

composed Latin letter, first to Dr. Alexander Monro, then professor of

anatomy, and afterwards to the other medical professors in the university,

from whom he immediately received gratis tickets of admission to their

different courses of lectures.

For two or three

years he supported himself by teaching the classics; but he afterwards

devoted himself to that occupation which is known at the university by the

familiar name of “grinding,” that is, preparing the medical candidates for

their probationary examinations, which are all conducted in Latin. For

composing a thesis, he charged ten guineas; and for translating one into

Latin, his price was five. In 1761 he became a member of the Royal Medical

Society, where, in the discussion of medical theories, he had an opportunity

of displaying his talents to advantage. He enjoyed the particular favour of

the celebrated Cullen, who received him into his family as tutor to his

children, and treated him with every mark of confidence and esteem. He even

made him assistant in his lectures – Brown illustrating and explaining to

the pupils in the evening the lecture delivered by Dr. Cullen in the

morning. In 1765, under the patronage of that eminent professor, he opened a

boarding-house for students attending the university, the profits of which,

with those of his professional engagements, enabled him to marry a Miss

Lamond, the daughter of a respectable citizen of Edinburgh. In spite of all

his advantages, however, his total want of economy, and his taste for

company and convivial pleasures, reduced him, in the course of three or four

years, to a state of insolvency, and he was under the necessity of calling a

meeting of his creditors, and making a compromise with them.

With the view of

qualifying himself for an anatomical professorship in one of the infant

colleges of America, he at this time devoted himself to obtaining an

intimate knowledge of anatomy and botany; but Cullen, who found him useful

in conducting his Latin correspondence, persuaded him to relinquish the

design of leaving Scotland. Soon afterwards he became a candidate for the

vacant chair of the theory of medicine, and was again unsuccessful, Dr.

Gregory having been appointed. On this occasion, an anecdote got into

circulation, which, if true, reflects little credit on his heretofore friend

and patron, Dr. Cullen. Coming forward without recommendation, it was

reported, that when the magistrates, who are the patrons of the

professorships, asked who this unfriended candidate was, Cullen, so far from

giving him his support, observed, with a sarcastic smile, “Surely this can

never be our Jock!” Attributing his disappointment to the jealousy of

Cullen, Brown resolved to break off all connection with him. This he did

after his rejection on applying to become a member of the society which

published the Edinburgh Medical Essays, admission into which Cullen could

easily have procured him.

Shortly after this

he commenced giving lectures in Latin upon a new system of medicine, which

he had formed in opposition to Cullen’s theories, and employed the

manuscript of his ‘Elementa Medicinae,’ composed some time previously, as

his text-book. The novelty of his doctrines procured him at first a numerous

class of pupils; and the contest between his partisans and those of his

opponents was carried to the highest possible extreme. In the Royal Medical

Society, the debates among the students on the subject of the new system

were conducted with so much vehemence and intemperance, that they frequently

terminated in a duel between some of the parties. A law was in consequence

passed, by which it was enacted that any member who challenged another on

account of anything said in the public debates, should be expelled the

society. In the autumn of 1779, Brown took the degree of M.D. at the

university of St. Andrews, his rupture with the professors of Edinburgh

preventing him for applying for it from that university. Not only the

medical professors, but the medical practitioners, were opposed to his

system, and he was visited with much rancorous obloquy and misrepresentation

by his opponent Dr. Cullen and his abettors. The imprudence of his conduct

in private life, and his intemperate habits, gave his enemies a great

advantage over him. One of his pupils informed Dr. Beddoes “that he used,

before he began to read his lecture, to take fifty drops of laudanum in a

glass of whisky, repeating the dose four or five times during the lecture.

Between the effects of these stimulants and his voluntary exertions, he soon

waxed warm, and by degrees his imagination was exalted into phrensy.”

His design seems

to have been to simplify the science of medicine, and to render the

knowledge of it easily attainable. All general or universal diseases were

reduced by him to two great families or classes, the sthenic and the

asthenic; the former depending upon an excess of excitement, the latter upon

a deficiency of it. Apoplexy is an instance of the former, common fever of

the latter. The former were to be removed by debilitating, the latter by

stimulating medicines, of which the most powerful are wine, brandy, and

opium; the stimuli being applied gradually, and with much caution.

“Spasmodic and convulsive disorders, and even hemorrhages,” he says in his

preface to the ‘Elementa Medicinae,’ “were found to proceed from debility;

and wine and brandy, which had been thought hurtful in these diseases, he

found the most powerful of all remedies in removing them.” In order to

prejudice the minds of the public against the “Brunonian system,” as it was

called, his enemies spread a report that its author cured all

diseases with brandy and laudanum, the latter of which, till the proper use

of it was pointed out by Dr. Brown, had been employed by physicians very

sparingly in the cure of diseases.

In 1780 he

published his ‘Elementa Medicinae,’ which his opponents did not venture

openly to refute, but those students who were known to resort to Dr. Brown’s

lectures were marked out, and in their inaugural dissertations at the

college, any allusion to his work, or quotation from it, was absolutely

prohibited. “Had a candidate,” says Dr. Brown’s son in the life of his

father prefixed to his works, “been so bold as to affirm that opium acted as

a stimulant, and denied that its primary action was sedative; or had he

asserted that a catarrh, or a similar inflammatory complaint, was occasioned

by the action of heat, or of heating things, upon a body previously exposed

for some time to cold, and that it would give way to cold and antiphlogistic

regimen – facts which are now no longer controverted – he might have

continued to enjoy his new opinions, but would have been very unlikely to

attain the object he had in view in presenting himself for examination.” The

number of students attending his classes became in consequence very much

reduced.

In 1776 Dr Brown

had been elected president of the Royal Medical Society, and,

notwithstanding the violent opposition made to his system by the older

physicians, he was again chosen to the chair in 1780. In 1785 he instituted

the Mason Lodge called the “Roman Eagle,” with the design of preventing, as

far as possible, the rapid decline of the language and literature of the

ancient Romans. Several gentlemen of talent and reputation became members of

this society; and among others the celebrated Crosbie, at that time one of

the chief ornaments of the Scottish bar. His motives in instituting this

lodge have been variously represented, and one of his biographers has

asserted, it appears erroneously, that it was with the view of “gaining

proselytes to his new doctrine.” The obligation signed by the members of the

institution sufficiently points out the objects of the association. Upon

this occasion he received the compliments of all who wished well to polite

literature. At the meetings of the institution, at which nothing but Latin

was spoken Brown usually presided and addressed the members in the Latin

language with fluency, purity, and animation. In the same year in which he

founded the Roman Eagle Lodge, he published anonymously his English work,

entitled ‘Outlines,’ in which, under the character of a student, he points

out the fallacy of former systems of medicine, and farther illustrates the

principles of his own doctrine. His excesses had gradually brought him and

his system into discredit with the public; and at one time his pecuniary

difficulties were so great, that he was reduced to the necessity of

concluding a course of lectures in prison, where he had been confined for

debt. In this distressing situation, a one hundred pound note was secretly

conveyed to him from an unknown person, who was afterwards traced to be the

late generous and patriotic Lord Gardenstone.

His prospects and

circumstances becoming worse daily, in the year 1786 he quitted his native

country for London, hoping that his merit would be better rewarded in the

capital of the empire than it had been in Edinburgh. He was now in the

fifty-first year of his age, and had a wife and eight children dependent on

him, but his expectations of success were very sanguine. Soon after his

arrival he delivered three successive courses of lectures at the Devil

Tavern, Fleet Street, which, being attended only by a few hearers, added

little to his income. From Mr. Johnson, bookseller, of St. Paul’s

Churchyard, he received a small sum for the first edition of the translation

of his ‘Elementa Medicinae,’ We learn from his son’s memoir of his life,

that about this time, in consequence of a paltry intrigue, he was deprived

of the situation of physician to the king of Prussia, that monarch having

written to his ambassador in London to find him out, and send him over to

Berlin, and another person of the name of Brown, an apothecary, having gone

to Prussia without the ambassador’s knowledge. It is also said that, on a

previous occasion, the interference of his enemies prevented him from

obtaining the professorship of medicine in the university of Padua, where

his system had many adherents, as well as in Italy generally. In Germany,

too, it found much favour, being propagated with great zeal by Girtanner and

Weikard. Having furnished his house in Golden Square on credit, the broker

from whom he got his furniture in a few months threw him into the King’s

Bench prison, without any previous demand for the money due to him. During

his confinement he was applied to by a bookseller, named Murray, for a

nostrum or pill, for which the popularity of his name would ensure an

extensive sale. As he was only offered a trifle for the property of it, he

rejected the proposal. Soon after he was solicited by no less than five

persons to make up a secret or quack medicine, but as they could never come

to terms, he steadily refused all their entreaties. Their object was to take

advantage of his necessities, and without making him an adequate recompense,

to extort from him the possession of a nostrum, which would have been a

fertile source of gain to them, but a disgrace to him as a respectable

physician. By the friendly assistance of a countryman of the name of Miller,

and the liberality of the late Mr. Maddison, stock-broker, of Charing Cross,

he at length obtained his liberty, in the early part of the year 1788.

He now applied

himself with earnestness to execute different works which he had planned

while in prison. Besides the translation of his ‘Elementa Medicinae,’ which

he had published, he proposed among other works to being out a new edition

of his ‘Observations;’ a ‘Treatise on the Gout,’ for which he was to receive

£500 from a bookseller; also a treatise on ‘The Operation of Opium on the

Human Constitution;’ a new edition of the ‘Elementa,’ with additions; and a

‘Review of Medical Reviewers.’ His prospects were beginning to brighten and

his practice to increase, when a sudden stroke of apoplexy at once put a

period to his life. and to the illusive hopes of future prosperity which he

had been cherishing. He died October 7, 1788, in the 53d year of his age;

having the day preceding that of his death, delivered the introductory

lecture of a fourth course, at his house in Golden Square. He had taken, as

was his custom, a considerable quantity of laudanum before going to bed, and

he died in the course of the night. In 1795 Dr. Beddoes published an edition

of his ‘Elements of Medicine,’ for the benefit of his family, with a life of

the author. In 1804 his eldest son, Dr. William Cullen Brown, published his

works, with a memoir of his father, in 3 vols. 8vo. Dr. Brown’s system was

undoubtedly one of a great ingenuity, but although some of his conclusions

have proved useful in the improvement of medical science, his opinions,

never generally adopted in practice, have long ago been abandoned by the

profession. In ‘Kay’s Edinburgh Portraits,’ Dr. Brown figures as a very

prominent character. His works are:

Elementa Medicinae.

Edin. 1780, 8vo. Editio altera plurimum emendata et integrum demum opus

exhibens. Edin. 1787, 2 vols. 8vo. 1794, 8vo.

Observations on

the Principles of the Old System of Physic, exhibiting a Compound of the New

Doctrine, Containing a new account of the state of Medicine, from the

present times backward to the restoration of the genuine learning in the

wester parts of Europe. Edin. 1787, 8vo.

Elements of

Medicine, translated from the Elementa Medicinae Brunonis; with large Notes,

Illustrations, and Comments, by the author of the original work. Lond. 1788,

2 vols. 8vo. Of this a new edition was published by Dr Beddoes, revised and

corrected, with a Biographical Preface. Lond. 1795, 2 vols. 8vo.

BROWN, JOHN,

an ingenious artist and elegant scholar, the son of a goldsmith and

watchmaker, was born in 1752 at Edinburgh, and was early destined to the

profession of a painter. In 1771 he went to Italy, where for ten years he

improved himself in his art. At Rome he met with Sir William Young and Mr.

Townley, and accompanied them as a draftsman into Sicily. Of the antiquities

of this celebrated island he took several very fine views in pen and ink,

which were exquisitely finished, and preserved the appropriate character of

the buildings which he intended to represent. On his return to Edinburgh he

gained the esteem of many eminent persons by his elegant manners and

instructive conversation on various subjects, particularly on those of art

and music, of both of which his knowledge was very extensive and accurate.

He was particularly honoured by the notice of Lord Monboddo, who gave him a

general invitation to his table, and employed him in making drawings in

pencil for him.

In the year 1786

he went to London, where he was much employed as a painter of small

portraits with black lead pencil, which, besides being correctly drawn,

faithfully exhibited the features and character of the persons whom they

represented. After some stay in London, the weak state of his health, which

had become impaired by his close application, induced him to try the effects

of a sea voyage; and he returned to Edinburgh, to settle his father’s

affairs, who was then dead. On the passage from London he grew rapidly

worse, and was at the point of death when the ship arrived at Leith. With

much difficulty he was conveyed to Edinburgh, and placed in the bed of his

friend and brother-artist, Runciman, whose death occurred in 1784. Here

Brown died, September 5, 1787.

In 1789 his

‘Letters on the Poetry and Music of the Italian Opera,’ 12mo, with an

introduction by Lord Monboddo, to whom they were originally written, was

published for the benefit of Brown’s widow. His lordship, in the fourth

volume of ‘The Origin and Progress of Language,’ speaking of Mr. Brown,

says: “The account that I have given of the Italian language is taken from

one who resided above ten years in Italy; and who, besides understanding the

language perfectly, is more learned in the Italian arts of painting,

sculpture, music, and poetry, than any man I ever met with. His natural good

taste he has improved by the study of the monuments of ancient art to be

seen at Rome and Florence; and as beauty in all the arts is pretty much the

same, consisting of grandeur and simplicity, variety, decorum, and a

suitableness to the subject, I think he is a good judge of language, and of

writing, as well as of painting, sculpture, and music,” A well written

character in Latin, by an advocate in Edinburgh, is appended to the Letters.

Mr. Brown left behind him several very highly finished portraits in pencil,

and many exquisite sketches in pencil and pen and ink, which he had taken of

persons and places in Italy. The peculiar characteristics of his hand were

delicacy, correctness, and taste, and the leading features of his mind were

acuteness, liberality, and sensibility, joined to a character firm,

vigorous, and energetic. His last performances were two exquisite drawings,

one from Mr. Tonwley’s celebrated bust of Homer, and the other from a fine

original bust of Pope, supposed to have been the work of Rysbrack. From

these two drawings, two beautiful engravings were made by Mr. Bartolozzi and

his pupil Mr. Bovi. a portrait of Brown with Runciman, disputing about a

passage in Shakspeare’s Tempest, the joint production of these artists, is

in the gallery at Dryburgh Abbey.

BROWN, ROBERT,

styled of Markle, an eminent agricultural writer, was born in 1757 in the

village of East Linton, Haddingtonshire, where he entered into business; but

his natural genius led him to agricultural pursuits, which he followed with

singular success. He commenced his agricultural career at Westfortune, and

soon afterwards removed to Markle. He was intimately acquainted with the

late George Rennie of Phantassie, who chiefly confined his energies to the

practice of agriculture; while Mr. Brown gave his attention to the literary

department. His ‘Treatise on Rural Affairs,’ and his articles in the

Edinburgh ‘Farmer’s Magazine,’ which he conducted for fifteen years, evinced

the soundness of his practical knowledge, and the vigour of his intellectual

faculties. His best articles have been translated into the French and German

languages. He died February 14, 1831, at Drylawhill, East Lothian, in his 74th

year.

BROWN, THOMAS,

an eminent metaphysician, youngest son of the Rev. Samuel Brown, minister of

Kirkmabreck, in the stewartry of Kirkcudbright, and of Mary, daughter of

John Smith, Esq., Wigton, was born at the manse of that parish, January 9,

1778. His father dying when he was not much more than a year old, his mother

removed with her family to Edinburgh, where he was by her early taught the

first rudiments of his education. It is said that he acquired the whole

alphabet in one lesson, and everything else with the same readiness, so much

so, that he was able to read the Scriptures when between four and five years

of age. In his seventh year, he was sent to a brother of his mother residing

in London, by whom he was placed at a school, first at Camberwell, and

afterwards at Chiswick. In these and two other academies to which he was

subsequently transferred, he made great progress in classical literature. In

1792, upon the death of his uncle, Captain Smith, he returned to Edinburgh,

and entered as a student at the university of that city. In the summer of

1793, being on a visit to some friends in Liverpool, he was introduced to

Dr. Currie, the biographer of Burns, by whom his attention was first

directed to metaphysical subjects; Dr. Currie having presented him with Mr.

Dugald Stewart’s ‘Elements of the Philosophy of the human mind,’ then just

published. The winter after, young Brown attended Mr. Stewart’s moral

philosophy class, in the college of Edinburgh; and at the close of one of

the lectures he went forward to that celebrated philosopher, though

personally unknown to him, and modestly submitted some remarks which he had

written respecting one of his theories. Mr. Stewart, after listening to him

attentively, informed him, that he had received a letter from the

distinguished M. Prevost of Geneva, containing similar arguments to those

stated by the young student. This proved the commencement of a friendship,

which Dr. Brown continued to enjoy till his death.

At the age of

nineteen, he was a member of that association which included the names of

Brougham, Erskine, Jeffrey, Birkbeck, Logan, Leyden, Sydney, Smith, Reddie,

and others, who established the academy of physics at Edinburgh, the object

of which was, “the investigation of Nature, and the laws by which her

phenomena are regulated.” From this society originated the publication of

the “Edinburgh Review.’ Some articles in the early numbers of that work, and

particularly the leading article in the 2d number, upon Kant’s Philosophy,

were written by Dr. Brown. In 1798 he published ‘Observations on the

Zoonomia of Dr. Darwin,’ the greater part of which was written in his

eighteenth year, and which contains the germ of all his subsequent views in

regard to mind, and of those principles of philosophising by which he was

guided in his future inquiries. In 1799 he was a candidate for the chair of

Rhetoric, and on the death of Dr. Finlayson, for that of Logic, but in both

cases unsuccessfully. In 1803, after attending the usual medical course, he

took his degree of M.D.

In the same year

he published the first edition of his poems in two vols., written

principally while he was at college. His next publication was an Examination

of the Principles of Mr. Hume respecting Causation, which was caused by a

note in Mr. Leslie’s Essay on Heat; and the great merits of which caused it

to be noticed in a very flattering manner in the Edinburgh Review, in an

able article by Mr. Horner. Professor Stewart also spoke very highly in

favour of Dr. Brown’s Essay, and Sir James Mackintosh has pronounced it the

finest model in mental philosophy since Berkeley. In 1806 he brought out a

second edition of this treatise, considerably enlarged; and in 1818 the

third addition appeared, with many additions, under the title of ‘An Inquiry

into the Relation of Cause and Effect.’ Having commenced practice as a

physician in Edinburgh he entered, in 1806, into partnership with the late

Dr. Gregory. Mr. Stewart’s declining health requiring him occasionally to be

absent from his class, he applied to Dr. Brown to supply his place; and in

the winter of 1808-9, the latter officiated for a short time as Mr.

Stewart’s substitute. “The moral philosophy class at this period,” says his

biographer, Dr. Welsh, “presented a very striking aspect. It was not a crown

of youthful students led into transports of admiration by the ignorant

enthusiasm of the moment; distinguished members of the bench, of the bar,

and of the pulpit, were daily present to witness the powers of this rising

philosopher. Some of the most eminent of th professors were to be seen

mixing with the students, and Mr. Playfair, in particular, was present at

every lecture. The originality, and depth, and eloquence of the lectures,

had a very marked effect upon the young men attending the university, in

leading them to metaphysical speculations.” In the following winter, Dr.

Brown’s assistance was again rendered necessary; and in 1810, in consequence

of a wish expressed by Mr. Stewart to that effect, he was officially

conjoined with him in the professorship. In the summer of 1814 he concluded

his poem called the ‘Paradise of Coquettes,’ which he published anonymously

in London, and which met with a favourable reception. In the succeeding year

he brought out another volume of poetry under the name of ‘The Wanderer in

Norway.’ In 1816 he wrote hie ‘Bower of Spring,’ near Dunkeld in Perthshire.

In 1818 he published a poetical tale, entitled ‘Agnes.’ In the autumn of

1819, at his favourite retreat in the neighbourhood of Dunkeld, he commenced

his text book, a work which he had long meditated for the benefit of his

students. Towards the end of December of the same year his health began to

give way, and after the recess, he was in such a state of weakness as to be

unable for some time to resume his official duties. His ill health having

assumed an alarming aspect, he was advised by his physicians to proceed to

London, as he had, upon a former occasion, derived great benefit from a sea

voyage. Accompanied by his two sisters he hastened to the metropolis, with

the intention of going to a milder climate as soon as the season allowed,

and took lodgings at Brompton, where he died, April 2, 1820. His remains

were put into a leaden coffin, and removed to Kirkmabreck, where they were

laid, according to his own request, beside those of his parents; his mother,

whom he tenderly loved, having died in 1817.

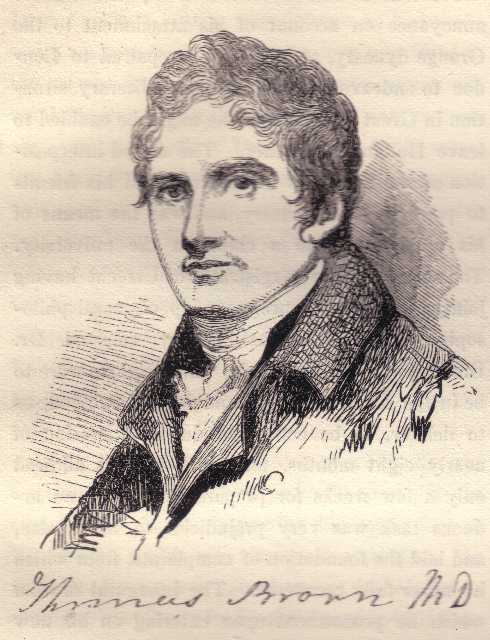

Dr. Brown was

rather above the middle height. A portrait of him by Watson, taken in 1806,

is said faithfully to preserve his likeness. The following woodcut of it is

from the engraving by W. Walker.

He was

distinguished for his gentleness, kindness and delicacy of mind, united with

great independence of spirit, a truly British love of liberty, and an ardent

desire for the diffusion of knowledge, virtue, and happiness among mankind.

All his habits were simple, temperate, studious, and domestic. As a

philosopher, he was remarkable for his power of analysing, and for that

comprehensive energy, which, to use his own words, “sees, through a long

train of thought, a distant conclusion, and separating, at every stage, the

essential from the accessory circumstances, and gathering and combining

analogies as it proceeds, arrives at length at a system of harmonious

truth.” As a poet, ‘Dr. Brown exhibited much taste and gracefulness, but his

poetry is not of a character ever to become popular. His lectures, which

were published after his death, in four volumes, 8vo, have passed through

several editions. An account of his life and writings was published by the

Rev. Dr. David Welsh, in one volume, 8vo, in 1825. His works are:

Observations on the Zoonomia of Erasmus Darwin, M.D. Edin. 1798, 8vo.

Poems, Edin. 1804, 2 vols. 12mo.

Observations on the Nature and Tendency of Mr. Hume’s Doctrine concerning

the Relation of Cause and Effect. Edin. 1806, 8vo. 3d edit., under the title

of An Enquiry into the Relation of Cause and Effect, 1818.

A

Short Criticism on the Terms of the Charges against Mr. Leslie, in the

Protest of the Ministers of Edinburgh. 1806, 8vo.

Examination of some Remarks in the Reply of Dr. John Inglis to Professor

Playfair. Edin, 1806, 8vo.

The

Paradise of Coquettes; a Poem. London, 1814, 8vo.

The

Wanderer in Norway; a Poem. London, 1815, 8vo.

The

War Fiend, 1816.

The

Bower of Spring, and other Poems, London, 8vo, 1817.

Agnes; a Poem. 1818, 8vo.

Emily; and other Poems. 2d edit. 1818, 8vo.

Lectures on the Philosophy of the Human Mind. 4 vols. 8vo. Edin. 1820.

System of the Philosophy of the Human Mind. 8vo. Edin. 1820.

BROWN,

WILLIAM LAWRENCE, D.D.,