|

BREADALBANE

(properly BROADALBIN), earl and marquis of, the former a title in the

peerage of Scotland, and the latter in that of Great Britain, possessed by a

branch of the noble family of Campbell. Sir Colin Campbell, the ancestor of

the Breadalbane family, and the first of the house of Glenurchy, was the

third son of Duncan, first Lord Campbell of Lochow, progenitor of the dukes

of Argyle, by Marjory Stewart, daughter of Robert, duke of Albany, regent of

Scotland. In an old manuscript, preserved in Taymouth castle, named ‘the

Black Book of Taymouth,’ (printed by the Bannatyne Club, 1853), containing a

genealogical account of the Glenurchy family, it is stated that “Duncan

Campbell, commonly callit Duncan in Aa, knight of Lochow (Lineallie

descendit of a valiant man, surnamit Campbell, quha cam to Scotland in King

Malcolm Kandmoir his time, about the year of God 1067, of quhom came the

house of Lochow,) flourisched in King David Bruce his dayes. The foresaid

Duncan in Aa had to wyffe Margarit Stewart, dochter to Duke Murdoch [a

mistake evidently for Robert], on whom he begat twa sones, the elder callit

Archibald, the other namit Colin, wha was first laird of Glenurchay.” That

estate was settled on him by his father. It had come into the Campbell

family, in the reign of King David the Second, by the marriage of Margaret

Glenurchy with John Campbell; and was at one time the property of the

warlike clan MacGregor, who were gradually expelled from the territory by

the rival clan, Campbell. Sir Colin was born about 1400. He was one of the

knights of Rhodes, afterwards designed of Malta. The family manuscript,

already quoted, says that “throch his valiant actis and manheid he was maid

knicht in the Isle of Rhodes, quhilk standeth in the Carpathian sea near to

Caria, and countrie of Asia the less, and he was three sundrie tymes in

Rome.? After the murder of James the First in 1437, he actively pursued the

regicides, and brought to justice two of the inferior assassins, named

Chalmers and Colquhoun, for which service King James the Third afterwards

bestowed upon him the barony of Lawers. He was appointed guardian of his

nephew, Colin, first earl of Argyle, during his minority, and concluded a

marriage between him and the sister of his own second wife, one of the three

daughters and co-heiresses of the Lord of Lorn. In 1440 he built the castle

of Kilchurn on a projecting rocky elevation at the east end of Lochawe,

under the shadow of the majestic Ben Cruachan, where – now a picturesque

ruin, –

............................................ “grey and stern

Stands, like a spirit of the past, lone old Kilchurn.”

According to tradition

Kilchurn (properly Coalchuirn) castle was first erected by his lady, and not

by himself, he being absent on a crusade at the time, and for seven years

the principal portion of the rents of his lands are said to have been

expended on its erection. An old legend connected with this castle states

that once while at Rome, having been a long time from home, Sir Colin had a

singular dream, for the interpretation of which he applied to a monk, who

advised him instantly to return to Scotland, as a very serious domestic

calamity could only be averted by his presence in his own castle. He

hastened immediately to Scotland, and arrived at a place called Succoth,

where dwelt an old woman who had been his nurse. In the disguise of a

beggar, he craved food and shelter for the night, and was admitted to the

poor woman’s fireside. From a scar on his arm she recognised him, and

immediately informed him of what was about to happen at the castle. It

appeared that for a long period no tidings had been received of or from him,

and a report had been spread that he had fallen in battle in the Holy Land.

This information surprised Sir Colin, as he had repeatedly sent messengers

with intelligence to his lady, and he at once suspected treachery. His

suspicions were well founded. A neighbouring baron, named M’Corquadale, had

intercepted and murdered all his messengers, and having succeeded in

convincing the lady of the death of her husband, he had prevailed upon her

to consent to marry him, the next day being that fixed for their nuptials.

Early in the morning Sir Colin, still in the disguise of a beggar, set out

for his castle of Kilchurn; he crossed the drawbridge, and undiscovered

entered the gates of the castle, which on this joyous occasion were open to

all comers. As he stood in the courtyard one of the servants of the castle

accosted him, and asked him what he wanted. “To have my hunger satisfied and

my thirst quenched,” was his reply. Food and liquor were immediately placed

before him. Of the former he partook, but he refused the latter, except from

the hand of the lady herself. On being informed of this, she approached, and

handed him a cup of wine. Sir Colin drank to her health, and dropping a ring

into the empty cup returned it to her. On examining the ring, she recognised

it at once as her own gift to her husband on his departure. Rushing towards

him she threw herself into his arms. The baron M’Corquadale was allowed to

depart in safety, but was afterwards attached and overcome by Sir Colin’s

son and successor, who is said to have taken possession of his castle and

lands. Sir Colin died before June 10, 1478, as on that day the lords

auditors gave a dectreet in a civil suit against “Duncain Cambell, son and

air of unquhile Sir Colin Cambell of Glenurquha, knight.” He was interred in

Argyleshire, and not as Douglas says at Finlarig, at the north-west end of

Lochtay, which afterwards became the burial place of the family. He was four

times married. Nisbet, giving as his authority the contract of marriage

still extant in the archives of the Breadalbane family, says, that his first

wife was Lady Mary Stewart, one of the daughters of Duncan, earl of Lennox,

and that she died soon after the marriage without issue, but he has

evidently mistaken the lady’s name, as the three daughters of Duncan, the

last earl of Lennox, executed in 1425, none of whom were named Mary, were

all married in 1392, eight years before Sir Colin Campbell was born, and

there never was another earl of Lennox named Duncan. His second wife was

Lady Margaret Stewart, the second of the three daughters and co-heiresses of

John Lord Lorn, with whom he got a third of that lordship, still possessed

by the family, and thenceforward quartered the galley of Lorn with his

paternal achievement. Of this lady there is a portrait by Jamesone in the

Breadalbane collection at Taymouth, an engraving of which is given in

Pinkerton’s Scottish gallery. By her he had a son, Sir Duncan, who succeeded

him. His third wife was Margaret, daughter of Robert Robertson of Strowan,

by whom he had a son and a daughter. John, the son, according to Nisbet, [Heraldry,

v. ii. p. 212,] was educated for the church, and on the demise of Angus,

bishop of the Isles, was preferred to that see. In 1506 he was joined in

commission frm the crown with David, bishop of Argyle, and James Redheugh,

burgess of Stirling, comptroller to the king, to set in tack the crown lands

of Bute. He died in 1509. Douglas, however, thinks the existence of this

John doubtful. [Peerage, v. i. p. 234.] Keith [Cat. of Scottish

Bishops, p. 305] leaves the surname blank, and says that John, bishop of

the Isles, was a privy councillor to King James the Fourth, and from that

prince, with consent of the Pope, he got, in 1507, the abbacy of Icolmkill

annexed in all time coming to the episcopal see of the Isles. The daughter,

Margaret, married first Archibald Napier of Merchiston, and secondly John

Dickson, Ross Herald. Sir Collin’s fourth wife was Margaret, daughter of

Luke Stirling of Keir, by whom he had a son, John, ancestor of the earls of

Loudon [see LOUDON, earl of], and a daughter, Mariot, married to William

Stewart of Baldoran.

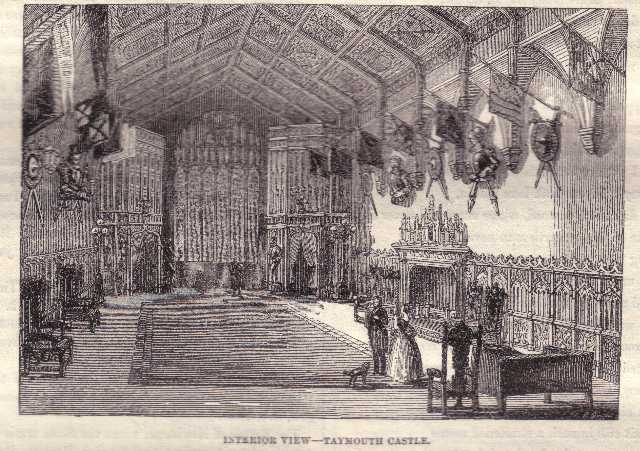

Interior view -

Taymouth Castle

Sir

Duncan Campbell, the eldest son, obtained the office of bailiary of the

king’s lands of Discher, Foyer, and Glenlyon, 3d September 1498, for which

office, being a hereditary one, his descendant, the second earl of

Breadalbane, received, on the abolition of the heritable jurisdictions in

Scotland, in 1747, the sum of one thousand pounds, in full of his claim for

six thousand. Sir Duncan also got charters of the king’s lands of the port

of Lochtay, &c., 5th March 1492; also of the lands of Glenlyon, 7th

September 1502; of Finlarig, 22d April 1503, and of other lands in

Perthshire in May 1508 and September 1511. He fell at the battle of Flodden.

He was twice married. First, in 1479, to Lady Margaret Douglas, fourth

daughter of George fourth earl of Angus, by whom nothing is known. The

daughter married Toshach of Monyvaird in Perthshire. The second wife was

Margaret, daughter of Moncrieff of Moncrieff in the same county, by whom he

had a son, John, styled by Douglas bishop of the Isles, )Keith states that

the John Campbell who was bishop of the Isles in 1558 and 1560 was a son of

Campbell of Calder in Nairnshire,) and two daughters, Catharine, married to

William Murray of Tullibardin, and Annabella, who in 1533 became the wife of

Alexander Napier of Merchiston.

Sir

colin, the eldest son, the third laird of Glenurchy, was of great use in

assisting his cousin, the celebrated Gavin Douglas, to obtain possession of

the see of Dunkeld to which he had been nominated in 1515, in opposition to

Andrew Stewart, his own brother-in-law, who having procured himself to be

chosen bishop by the chapter, had garrisoned the palace and the steeple of

the cathedral with his servants. This Sir Colin is mentioned as having

“bigget the chapel of Finlarig to be ane burial for himself and posteritie.”

He married Lady Marjory Stewart, sixth daughter of John earl of Athol,

brother uterine of King James the Second, and had three sons, viz., Sir

Duncan, Sir John, and Sir Colin, who all succeeded to the estate. The last

of them, Dir Colin, became laird of Glenurchy in 1550, and according to the

“Black Book of Taymouth,” he “conquessit” (that is, acquired) “the

superiority of M’Nabb his heill landis.” He was among the first to join the

Reformation, and sat in the parliament of 1560, when the Protestant

doctrines received the sanction of the law. In 1573 he was one of the

commissioners for settling a firm and lasting government in the church. In

the “Black Book of Taymouth,” he is represented to have been “ane great

justiciar all his tyme, throch the quhilk he sustenit the deidly feid of the

Clangregor ane lang space; and besides that he causit execute to the death

many notable lymarris, he behiddit the laird of Macgregor himself at

Kandmoir, in presence of the Erle of Athol, the justice-clerk, and sundrie

other nobilmen.” In 1580 he built the castle of Balloch, in Perthshire, one

wing of which still continues attached to Taymouth Castle, the splendid

mansion of the Marquis of Breadalbane. He also built Edinample, another seat

of the family. Sir Colin died in 1583. By his wife, Catherine, second

daughter of William, second lord Ruthven, he had four sons and four

daughters. Archibald, the fourth son, got part of the barony of Monzie by

his marriage with Margaret, daughter and heiress of Andrew Toshach of Monzie,

but had no issue. Beatrix, the eldest daughter, married Sir John Campbell of

Lawers; Margaret, the second, married, in 1574, James, seventh earl of

Glencairn, and had issue; Mary, the third, married John, sixth earl of

Menteith, with issue; and Elizabeth, the youngest, became the wife of Sir

John Campbell of Ardkinglass.

Sir

Duncan Campbell of Glenorchy, the eldest son, was named by King James the

Sixth, 18th May 1590, one of the barons to assist at the

coronation of his queen, Anne of Denmark, when he was knighted. On the death

of Colin, sixth earl of Argyle, in 1584, he had been nominated by that

nobleman’s will, one of the six guardians of the young earl, then a minor,

the others being Dougal Campbell of Auchinbreck, John Campbell of Calder,

Sir James Campbell of Ardkinglass, comptroller to the king, father of the

above-named Sir John, Archibank Campbell of Lochnell, and Neill Campbell,

bishop of Argyle. The guardians soon split into rival factions, Glenorchy,

Auchinbreck, and Lochnell, who was the nearest heir to the earldom, being on

the one side, and Calder, Ardkinglass, and the bishop on the other. The

influence of the three latter preponderated, but jealousies soon broke out

between Ardkinglass and Calder, and on the death of the former in 1591, his

feelings of hostility were transmitted to his son and successor, Sir John,

who being of a weak and vacillating disposition, was easily induced by his

brother-in-law Glenurchy to enter into his plans. The principal

administration of the affairs of the earldom now centered in Calder. He was

supported by many of the nobility connected with the family of Argyle, and

particularly by the earl of Murray, commonly called the “bonnie earl,” who

was murdered in his own house of Donnibirsel in Fife, in February 1592, by a

party of the Gordons, under the command of the earl of Huntly. In the same

month John Campbell of Calder was assassinated in Lorn. Both crimes, by a

late discovery, appear to have been the result of the same conspiracy, in

which Glenurchy and other barons and chiefs in the West Highlands were

involved, and one object of which was the death of the young earl of Argyle,

as well as that of the “bonnie earl of Murray.” Gregory expressly charges

Sir Duncan Campbell of Glenurchy with being the principal mover in the

branch of the plot which led to the murder of Calder. “Glenurchy,” he says,

“knowing the feelings of personal animosity cherished by Ardkinglass against

Calder, easily prevailed upon the former to agree to the assassination of

their common enemy, with whom Glenurchy himself had now an additional cause

of quarrel, arising from the protection given by Calder to some of the

Clangregor who were at feud with Glenurchy. After various unsuccessful

attempts, Ardkinglass procured, through the agency of John Oig Campbell of

Cabrachan, a brother of Lochnell, the services of a man named M’Ellar, by

whom Calder was assassinated with a hackbut, supplied by Ardkinglass, the

fatal shot being fired at night through one of the windows of the house of

Knepoch in Lorn, when Calder fell, pierced through the heart with three

bullets. Owing to his hereditary feud with Calder, Ardkinglass was generally

suspected, and being, in consequence, threatened with the vengeance of the

young earl of Argyle, Glenurchy ventured to communicate to him the plan for

getting rid of the earl and his brother, and for assisting Lochnell to seize

the earldom. Ardkinglass refused, although repeatedly urged, to become a

party to any designs against the life of the earl, proposing to make his

peace with Argyle, by disclosing the full extent of the plot. The inferior

agents, John Oig Campbell and M’Ellar, were both executed; nor could all the

influence of Calder’s relations or friends obtain the punishment of any of

the higher parties. Glenurchy was allowed to clear himself of all concern in

the plots attributed to him, by his own unsupported and extrajudicial denial

in writing. He offered to abide his trial, which, he well knew, the

chancellor, Thirlestane, and the earl of Huntly were deeply interested in

preventing.” [History of the Western Highlands and Isles, pp.

250-253.]

In

1617 Sir Duncan had the office of heritable keeper of the forest of Mamlorn,

Bendaskerlie, &c., conferred upon him. He afterwards obtained from King

Charles the First the sheriffship of Perthshire for life. He was created a

baronet of Nova Scotia by patent, bearing date 30th May 1625.

Although represented as an ambitious and grasping character, he is said to

have been the first who attempted to civilize the people on his extensive

estates. He not only set them the example of planting timber trees, fencing

pieces of ground for gardens, and manuring their lands, but assisted and

encouraged them in their labours. One of his regulations of police for the

estate was “that no man shall in any public house drink more than a chopin

of ale with his neighbour’s wife, in the absence of her husband, upon the

penalty of ten pounds, and sitting twenty-four hours in the stocks, toties

quoties.” [New Scot. Account, vol. x. p. 464.] According to the

‘Black Book of Taymouth,’ “in the zeir of God 1627, he causit big ane brig

over the watter of Lochay, to the great contentment and will of the

countrie.” He died in June 1631. He was twice married, first, in 1574, to

Lady Jean Stewart, second daughter of John earl of Athol, lord high

chancellor of Scotland, by whom he had seven sons and three daughters.

Archibald Campbell of Monzie, the fifth son, was ancestor of the Campbells

of Monzie, Lochlane, and Finnah, in Perthshire. Jean, the eldest daughter,

married Sir John Campbell of Calder, and had issue; Anne, the second,

married Sir Patrick Ogilvy of Inchmartine, and was mother of the second earl

of Findlater; Margaret, the third, married Sir Alexander Menzies of Weem.

His second wife was Elizabeth, only daughter of Patrick fifth Lord Sinclair,

by whom he had a son, Patrick, on whom his father settled the lands of

Edinample, and a daughter, Jean, married to John earl of Athol, and had

issue.

His

second son, Robert, was engaged in 1610 in the Fight or Skirmish of

Bintioch, also known as ‘the Chase of Ranefray,’ against the M’Gregors. The

fight appears to have taken place at Bintioch, and the chase or pursuit to

have reached as far as Ranefray. The transaction is thus narrated in ‘the

Book of Taymouth:’ “Attoure, Robert Campbell, second sone to the Laird (of

Glenurquhey) Sir Duncan, persewing ane great number of them (the Clan

Gregor) through the countrie, in end overtuik them in Ranefray, in the Brae

of Glenurchy; quhair he slew Duncan Abrok Makgregor, with his son Gregor in

Ardchyllie, Dougall Makgregor M’Coulchier in Glengyle, with his son Duncan,

Charles Makgregor (M’) Cane in Bracklie, quha was principallis in that band;

and twenty utheris of their compleises slain in the chaiss.” A contemporary

historian, Sir Robert Gordon, in his ‘History of the Earldom of Sutherland,’

(p. 247), says of this affair, that “here (meaning at Bintioch) Robert

Campbell, the laird of Glen-Vrquhie his sone, accompanied with some of the

Clanchamron, Clanab (M’Nabs), and Clanroland, to the number of two hundred

chosen men, faught against three score of the Clangregar; in which conflict

tuo of the Clangregar were slain, to wit, Duncan Aberigh, one of the

chieftanes, and his son Duncan. Seavon gentlemen of the Campbell’s syd wer

killed ther, though they seemed to have the victorie.” The same Robert

Campbell, styled of Glenfalloch, in January 1611, besieged a garrison of the

Clan Gregor in the small island of Varnak, near the western extremity of

Loch Katrine, on its north shore, opposite Portnellan, but he was obliged to

abandon the siege, owing, as stated in ‘the Book of Taymouth,’ to a storm of

snow. In July 1612 several of the Clan Gregor were hanged at the

Borough-muir of Edinburgh for the slaughter of a bowman of the laird of

Glenurchy and eight other persons, and several other crimes, consisting of

fire-raising, theft, and intercommuning with their proscribed clansmen.

Sir

Colin Campbell, the eldest son of Sir Duncan, born about 1577, succeeded as

eighth laird of Glenurchy. Little is known of this Sir Colin, save what is

highly to his honour, namely his patronage of George Jamesone, the

celebrated portrait painter. The family manuscript which records the

genealogy of the house of Glenurchy contains the following entries, written

in 1635: – “Item, the said Sir Coline Camppell gave unto George Jamesone,

painter in Edinburgh, for King Robert and King David Bruysses, kings of

Scotland, and Charles I. king of Great Brittane, France and Ireland, and his

majesties quein, and for nine more of the queins of Scotland, their

portraits, quhilks are set up in the hall of Balloch, (new Taymouth) the sum

of tua hundreth thrie scor punds. – Mair, the said Sir Coline gave to the

said George Jamesone for the knight of Lochow’s lady, and the first countess

of Argylle, and six of the ladys of Glenurquhay, their portraits, and the

said Sir Coline his own portrait, quhilks are set up in the chalmer of deas

(principal presence room) of Balloch, ane hundreth four scoire punds.” The

family tree of the house of Glenorchy, eight feet long by five broad,

described by Pennant, was also painted by Jamesone. In a corner is inscribed

“The genealogie of the House of Glenurquhie, quhairof is descendit sundrie

nobil and worthie houses, 1635, Jameson faciebat.” Sir Colin married

Lady Juliana Campbell, eldest daughter of Hugh first Lord Loudon, but had no

issue. He died 6th September 1640, aged 63. In Pinkerton’s

Scottish Gallery are portraits of Sir Colin at the age of 56, and of Lady

Juliana, his spouse, at the age of 52, both taken from the original

paintings in the Breadalbane collection at Taymouth Castle.

He

was succeeded by his brother, Sir Robert, at first styled of Glenfalloch,

and afterwards of Glenurchy. “In the year of God 1644 and 1645, the laird of

Glenurquhay his whole landis and esteat, betwixt the foord of Lyon and point

of Lismore, were burnt and destroyit be James Graham, some time erle of

Montrose, and Alex. M’Donald, son to Col. M’Donald in Colesue, with their

associattis. The tenants their whole cattle were taken away be their

enemies; and their cornes, houses, plenishing, and whole insight weir burnt;

and the said Sir Robert pressing to get the inhabitants repairit, wairit £48

Scots upon the bigging of every cuple in his landis, and als wairit seed

cornes, upon his own charges, to the most of his inhabitants. The occasion

of this malice against Sir Robert, and his friends and countrie people, was,

because the said Sir Robert joinit in covenant with the kirk and kingdom of

Scotland, in maintaining the trew religion, the kingis majestie, his

authoritie, and laws, and libertie of the kingdom of Scotland; and because

the said Sir Robert altogether refusit to assist the said James Graham and

Alex. M’Donald, their malicious doings in the kingdom of Scotland. So that

the laird of Glenurquhay and his countrie people, their loss within

Perthshire and within Argyleshire, exceeds the soume of 1,200,000 merks.”

Sir Robert married Isabel, daughter of Sir Lachlan Macintosh, of Torecastle,

captain of the clan Chattan, and had five sons and nine daughters. William,

the third son, was ancestor of the Campbells of Glenfalloch, the

representative of whom is now the heir presumptive to the Scottish titles of

earl of Breadalbane, &c. Alexander, the fourth son, got from his father the

lands of Lochdochart in 1648, and was ancestor of the Campbells of

Lochdochart. Duncan, the fifth son, possessed Auchlyne, and from him

descended the now deceased James Goodlet Campbell of Auchlyne, who by his

wife, a sister of Logan of Logan, had a son, Hugh Campbell, merchant in

Glasgow. Margaret, the eldest daughter, married to John Cameron of Lochiel,

was the mother of Sir Ewen Cameron; Mary, the second daughter, married James

Campbell of Ardkinglass; Jean, the third, became the wife of Duncan Stewart

of Appin; Isabel, the fourth, of Robert Irvine of Fedderet, son of Sir

Alexander Irvine of Drum, and Julian, the fifth, of John Maclean of

Lochbury. The other daughters were the wives respectively of Robertson of

Jude, Robertson of Faskally, Toshach of Monyvaird, and Campbell of Glenlyon.

The

eldest son, Sir John Campbell of Glenurchy, married first, Lady Mary Graham,

eldest daughter of William, earl of Strathern, Menteath, and Airth, and had

a son, Sir John, first earl of Breadalbane, and a daughter, Agnes, who

became the wife of Sir Alexander Menzies of Weem, baronet. Sir John married,

secondly, Christian, daughter of John Muschet of Craighead in Menteith, by

whom he had several daughters, of whom are descended the Campbells of

Stonefield, Airds, and Ardchattan. Isabel, one of them, was married to John

Macnachtane, and Anne, another, to Robert Macnab of Macnab, whom she

survived, and died at Lochdochart 6th September 1765.

Sir

John Campbell of Glenurchy, first earl of Breadalbane, only son of Sir John,

was born about 1635. He gave great assistance to the forces collected in the

Highlands for Charles the Second in 1653, under the command of General

Middleton, He subsequently used his utmost endeavours with General Monk to

declare for a free parliament, as the most effectual way to bring about his

majesty’s restoration. He served in parliament for the shire of Argyle.

Being a principal creditor of George, sixth earl of Caithness, [see

CAITHNESS, earl of,] whose debts are said to have exceeded a million of

marks, that nobleman, on 8th October 1672, made a disposition of

his whole estates, heritable jurisdictions, and titles of honour, after his

death, in favour of Sir John Campbell of Glenurchy, the latter taking on

himself the burden of his lordship’s debts, and he was, in consequence, duly

infefted in the lands and earldom of Caithness, 27th February

1673. The earl of Caithness died in May 1676, when Sir John Campbell

obtained a patent creating him earl of Caithness, dated at Whitehall, 28th

June 1677. But George Sinclair of Keiss, the heir male of the last earl,

being found by parliament entitled to that dignity, Sir John Campbell

obtained another patent, 13th August 1681, creating him instead,

earl of Breadalbane and Holland, Viscount of Tay and Paintland, Lord

Glenurchy, Benederaloch, Ormelie, and Weik, with the precedency of the

former patent, and remainder to whichever of his sons by his first wife he

might designate in writing, and ultimately to his heirs male whatsoever. On

the accession of James the seventh, the earl was sworn a privy councillor.

At the Revolution he adhered to the Prince of Orange, and after the battle

of Killiecrankie and the attempted reduction of the Highlands by the forces

of the new government, he was empowered to enter into a negotiation with the

Jacobite chiefs to induce them to submit to King William, and a sum of

fifteen thousand pounds sterling was placed at his disposal for the purpose

by his majesty. This negotiation was for a time interrupted, principally at

the instigation of Mackian or Alexander Macdonald of Glencoe, between whom

and the earl a difference had arisen respecting certain claims which his

lordship had against Glencoe’s tenants for plundering his lands, and for

which the earl insisted for compensation and for retention out of Glencoe’s

share of the money with which he had been intrusted by the government to

distribute among the chiefs. The failure of the negotiation was extremely

irritating to the earl, who threatened Glencoe with his vengeance. Following

up this threat, he entered into a correspondence with Secretary Dalrymple,

the master of Stair, and between them, it is understood, a plan was

concerted for cutting off the chief and his people. Whether the “mauing

scheme” of the earl, to which Dalrymple alludes in one of his letters,

refers to a plan for the extirpation of the tribe, is a question which must

ever remain doubtful; but there is reason to believe that if he did not

suggest, he was at least privy to the foul massacre of that unfortunate

chief and his people, an event which has stamped an infamy upon the

government of King William, which nothing can efface.

“The hand that mingled in the meal,

At midnight drew the felon steel,

And gave the host’s kind breast to feel

Meed for his hospitality!

The friendly hearth which warmed that hand,

At midnight armed it with the brand,

That bade destruction’s flames expand

Their red and fearful blazonry.

There woman’s shriek was heard in vain,

Nor infancy’s unpitied plain,

More than the warrior’s groan, could gain

Respite from ruthless butchery!

The winter wind that whistled shrill,

The snows that night that cloaked the hill,

Though wild and pitiless, had still

Far more than Southern clemency.”

On

the 29th April 1695, upwards of three years after the massacre, a

commission was issued to inquire into it. The commissioners appear to have

discovered no evidence to implicate the earl of Breadalbane, but merely say,

in reference to him, that it “was plainly deponed” before them, that, some

days after the slaughter, a person waited upon Glencoe’s sons, and

represented to them that he was sent by Campbell of Balcalden, the earl’s

chamberlain or steward, and authorized to say that, if they would declare,

under their hands, that his lordship had no concern in the massacre, they

might be assured the earl would procure their “remission and restitution.”

While, however, the Commissioners were engaged in the inquiry they

ascertained that, in his negotiations with the Highland chiefs, the earl had

acted in such a way as to lay himself open to a charge of high treason, in

consequence of which discovery, he was, 10th June 1695, committed

prisoner to the castle of Edinburgh; but he was soon released from

confinement, as it turned out that he had professed himself a Jacobite, that

he might the more readily execute the commission with which he had been

intrusted, and that King William himself was a party to this contrivance.

When the earl of Nottingham, on the part of the English government, wrote to

Lord Breadalbane to account for the money he had received for the Jacobite

chiefs, the latter returned this laconic answer; “My lord, the Highlands are

quiet, the money is spent, and this is the best way of accounting among

friends.” When the treaty of union was under discussion, his lordship kept

aloof, and did not even attend parliament. At the general election of 1713,

he was chosen one of the sixteen Scots representative peers, being then

seventy-eight years old. At the breaking out of the rebellion of 1715, he

sent five hundred of his clan to join the standard of the Pretender, and he

was one of the suspected persons, with his second son, Lord Glenorchy,

summoned to appear at Edinburgh within a certain specified period, to give

bail for their allegiance to the government., but no farther notice was

taken of his conduct. The earl died in 1716, in his 81st year.

Macky [Memoirs, p. 199] erroneously styles him Marquis of

Breadalbane, and says, “It is odds if he live long enough but he is a duke.

He is of a fair complexion, and has the gravity of a Spaniard, is as cunning

as a fox, wise as a serpent, and as slippery as an eel.” His lordship

married, first, at London, 17th December 1657, Lady Mary Rich,

third daughter of Henry first earl of Holland, who was executed for his

loyalty to Charles the First, 9th March 1649. The marriage is

thus entered in the register of the parish of St. Andrews, Baynard Castle: –

“Mr. John Campbell of Glanorchy, in the county of Perth, in the

nation of Scotland, Esqr., was married to the Lady Mary Rich.” By

this lady he had two sons, Duncan, styled Lord Ormelie, who survived his

father, but was passed over in the succession, and John, in his father’s

lifetime styled Lord Glenorchy, who became second earl of Breadalbane. He

married, secondly, 7th April 1678, Lady Mary Campbell, third

daughter of Archibald, Marquis of Argyle, dowager of George, sixth earl of

Caithness, and by her had a son, Hon. Colin Campbell of Ardmaddie, who died

in 1708, aged 29. By a third wife he had a daughter, Lady Mary, married to

Archibald Cockburn of Langton.

John

Campbell, Lord Glenorchy, the second son, born 19th November

1662, was by his father nominated to succeed him as second earl of

Breadalbane, in terms of the patent conferring the title. In 1721, at the

keenly contested election for a representative of the Scots peerage, in room

of the Marquis of Annandale deceased, his right to the peerage was impugned

on the part of his elder brother, on the ground that any disposition or

nomination from his father to the honours and dignity of earl of Breadalbane

“could not convey the honours, nor could the crown effectually grant a

peerage to any person and such heir as he should name, such patent being

inconsistent with the nature of a peerage, and not agreeable to law, and

also without precedent.” [Robertson’s Proceedings, p. 88.] These

objections were overruled. At the general election of 1736 his lordship was

chosen one of the sixteen representative peers, and in 1741 was rechosen. He

was lord-lieutenant of the county of Perth. He died at Holyroodhouse, 23d

February 1752, in his ninetieth year. He married, first, Lady Frances

Cavendish, second of the five daughters of Henry, second duke of Newcastle.

She died, without issue, 4th February 1690, in her thirtieth

year. He married, secondly, 23d May 1695, Henrietta, second daughter of Sir

Edward Villiers, knight, sister of the first earl of Jersey, and of

Elizabeth, countess of Orkney, the witty but plain-looking mistress of King

William the Third. By his second wife he had a son, John, third earl, and

two daughters, Lady Charlotte and Lady Henrietta, who both died unmarried.

John, third earl, burn in 1696, was educated at the university of Oxford,

and when very young he exhibited an unusual degree of talent as well as

progress in his studies. In 1718, at the age of twenty-two, he was sent as

envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to the court of Denmark. He

was invested with the order of the Bath at its revival, in 1725. At the

general election of 1727 he was chosen member of parliament for the borough

of Saltash in England, and in 1734 was re-elected. In December 1731, he was

appointed ambassador to Russia. In 1741 he was chosen to represent Oxford in

Parliament, and spoke frequently in the House of commons in support of Sir

Robert Walpole’s measures. On 14th May 1741, he was appointed one

of the lords of the admiralty, but was removed from that board, 19th

March 1742, on the dissolution of the Walpole administration. In January

1746 he was nominated master of his majesty’s jewel office. In February 1752

he succeeded his father, and was elected a representative peer, 9th

July of that year, in the room of the earl of Dunmore, deceased. In 1761, he

was appointed lord chief justice in eyre of all the royal forests south of

the Trent, and he held that office till October 1765. He was constituted

vice-admiral of Scotland, 26th October 1776. He died at

Holyroodhouse, 26th January 1782, in his 86th year. He

married, first, in 1721, Lady Amabella Grey, eldest daughter and coheir of

Henry duke of Kent, K.G., and by her – who died at Copenhagen in March 1727

– he had a son, Henry, whose death took place a few weeks after his mother,

and a daughter, Lady Jemima Campbell, born 9th October 1723, who

succeeded her grandfather, the duke of Kent, as Baroness Lucas of Crudwell

and Marchioness de Grey, 6th June 1740. This lady married, 22d

May of that year, Philip, second earl of Hardwicke, and by him had two

daughters. The eldest, Lady Amabella Yorke, who married Lord Polwarth, son

of the third earl of Marchmont, succeeded her mother as Baroness Lucas in

1797, the title of Marchioness de Grey then becoming extinct. Lord

Breadalbane married, secondly, 23d January 1730, Arabella, third daughter

and heiress of John Pershall, by Charlotte, daughter of Thomas Lord

Colepepper, by whom he had two sons: George, born in January 1733, died at

Moffat in April 1744, in the twelfth year of his age; and John, Lord

Glenorchy, born in London 26th September 1738, died in the

lifetime of his father, and without surviving issue, at Barnton, in the

county of Edinburgh, an estate he had recently purchased, 14th

November 1771, in the 34th year of his age. He married at London,

26th September 1761, Willielma, second and posthumous daughter

and coheir of William Maxwell of Preston, a branch of the Nithsdale family,

and had a son, who died in his infancy. Of this lady, the celebrated Lady

Glenorchy, a memoir is given under the head of CAMPBELL, Willielma.

The

male line of the first peer having become extinct in 1782, on the death of

the third earl, the clause in the patent in favour of heirs general

transferred the peerage, and the vast estates belonging to it, to his

kinsman, John Campbell, born in 1762, eldest son of Colin Campbell of

Carwhin, descended from Colin Campbell of Mochaster, (who died in October

1688), second son of Sir Robert Campbell of Glenurchy. The mother of the

fourth earl and first marquis of Breadalbane, was Elizabeth, daughter of

Archibald Campbell of Stonefield, sheriff of Argyleshire, and sister of John

Campbell, judicially styled Lord Stonefield, a lord of session and

justiciary. He was educated at Westminster school; and afterwards resided

for some time at Lausanne in Switzerland. In 1784, he was elected one of the

sixteen representative peers of Scotland, and was rechosen at all the

subsequent elections, until he was created a peer of the United Kingdom in

November 1806, by the title of Baron Breadalbane of Taymouth in the county

of Perth, to himself and the heirs male of his body. In 1793 he raised a

forcible regiment, called the Breadalbane Fencibles, for the service of

government. It was afterwards increased to four battalions. One of these was

in July 1795 enrolled, as the 116th regiment, in the regular

service, his lordship being constituted its colonel. He was one of the state

counsellors of the prince of Wales for Scotland, and ranked as major-general

in the army from 25th October 1809. In 1831, at the coronation of

William the Fourth, he was created a marquis of the United Kingdom, under

the title of marquis of Breadalbane and earl of Ormelie. In public affairs

he did not take a prominent or ostentatious part, his attention being

chiefly devoted to the improvement of his extensive estates, great portions

of which, being unfitted for cultivation, he laid out in plantations. In

1805, he received the gold medal of the Society of Arts, for his success in

planting forty-four acres of waste land, in the parish of Kenmore, with

Scotch and larch firs, a species of rather precarious growth, and adapted

only to peculiar soils. In the magnificent improvements at Taymouth, his

lordship displayed much taste; and the park has been frequently described as

one of the most extensive and beautiful in the kingdom.

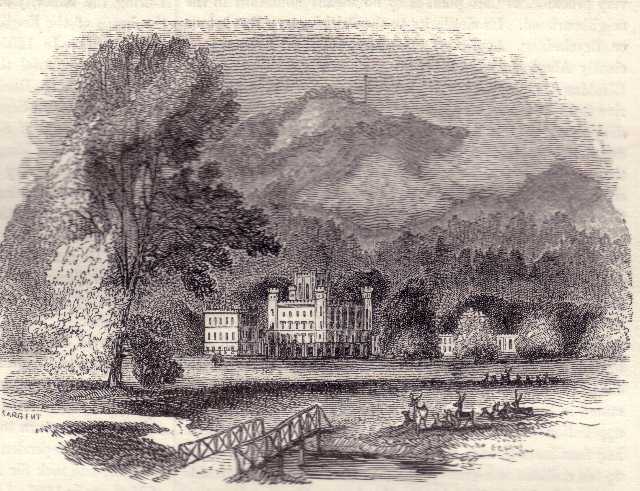

View of Taymouth

Castle

He

married, 2 September, 1793, Mary Turner, eldest daughter and coheiress of

David Gavin, Esq. of Langton, in the county of Berwick, by Lady Elizabeth

Maitland, eldest surviving daughter of James, seventh earl of Lauderdale,

and by her had two daughters and one son. The elder daughter, Lady Elizabeth

Maitland Campbell, married in 1831, Sir John Pringle of Stitchell, baronet,

and the younger, Lady Mary Campbell, became in 1819 the wife of Richard,

marquis of Chandos, who in 1839 became duke of Buckingham. The marquis died,

after a short illness, at Taymouth castle, on 29th march 1834,

aged seventy-two. The whole of his personal estate, exceeding, it is said,

£300,000, was directed by his will to accumulate for twenty years, at the

end of which period it was to be laid out on estates to be added to the

entailed property, but his settlement was partly set aside by the marquis of

Chandos in right of his wife, who obtained an affirmance by the House of

Peers of the decision of the Court of Session, declaring that the

marchioness and her husband, in her right, were entitled to demand

legitim.

The

marquis’ only son, John Campbell, earl of Ormelie, born at Dundee, 26th

October 1796, succeeded, on the death of his father, to the titles and

estates. He married, 23d November 1821, Eliza, eldest daughter of George

Baillie, Esq. of Jerviswood, without issue. He represented Perthshire in the

parliament of 1832. In 1838 he was made a knight of the Thistle, and in 1841

was elected Lord Rector of the university of Glasgow. In 1848 he was

appointed Lord-chamberlain, and sworn a member of the privy council. He is

president of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. The father of his

marchioness made a fortune in the Netherlands, and returning to Scotland,

purchased, in 1758, the beautiful estate of Langton, the ancient seat of the

Cockburns, in Berwickshire. The heir presumptive to the Scotch titles of

Breadalbane is William John Lamb Campbell of Glenfalloch, Perthshire, born

in 1790, the descendant and representative of the first earl’s uncle. |