|

BEATTIE, JAMES, LL.D.,

a distinguished poet, moralist, and miscellaneous writer, was born at

Laurencekirk, Kincardineshire, October 25th, 1735. His father,

who kept a little retain shop in that village, also rented a small farm in

the neighbourhood, in which his forefathers had lived for many generations.

He was the youngest son, and his father dying when he was yet a child, his

elder brother David, on whom, with his mother, the care of the family

devolved, placed him at the village school, where, as he soon began to write

verses, his companions bestowed on him the title of “The Poet.” In 1749 he

was removed to Marischal College, Aberdeen, where he obtained a bursary or

exhibition. He studied Greek under Dr. Thomas Blackwell, author of ‘The

Court of Augustus,’ and ‘An Inquiry into the Life and Writings of Homer,’

who was the first to encourage Beattie’s genius. He made great progress in

his studies, and acquired that accurate and classical knowledge for which he

was afterwards so eminent. In 1753 he obtained the degree of A.M., and

having completed his course of study, he was appointed in August of that

year schoolmaster and parish clerk to the parish of Fordoun, at the foot of

the Grampians, six miles from his native village. It is related of him that

he loved at this time to wander in the fields during the night, and watch

the appearance of the doming dawn, feeding his young dreams of poesy “in

lone sequestered spots.” His early productions, inserted in the Scottish

Magazine, gained him some local reputation; and he attracted the favourable

notice of Mr. Garden, advocate, afterwards Lord Gardenstone, then sheriff of

Kincardineshire, Lord Monboddo, and others in the neighbourhood, who invited

him to their houses, and with whom he ever after maintained a friendly

intercourse. He had at one time an intention of entering the church; and in

consequence attended the divinity class at Marischal College; but

circumstances led him to change his views. In 1757, a vacancy occurred in

the grammar school of Aberdeen, and Beattie was induced to become a

candidate for the situation, but did not succeed. He acquitted himself so

well, however, that on a second vacancy in June 1758, he was elected one of

the masters of that school. In 1760 he published at London a volume of poems

and translations, which, though it met with a favourable reception, he

endeavoured at a future period, when his fame was established, to buy up and

suppress. Some of these will be found in the Appendix to Sir William Forbes’

Life of Beattie. By the influence of the earl of Errol and others of his

friends, he was the same year appointed professor of moral philosophy and

logic at Marischal college. Among his brother professors in the Aberdeen

universities at that time were such men of genius and learning as Dr.

Campbell, Dr. Reid, and Dr. Gregory. In 1762 he wrote his ‘Essay on Poetry,’

which was published in 1776, with others of his prose works. In 1765 he

published an unsuccessful poem on “The Judgment of Paris,’ in quarto. He

afterwards reprinted it in a new edition of his poetical works which

appeared in 1766. On the 28th June 1767 he married Mary, daughter

of Dr. James Dunn, the Rector of the grammar school at Aberdeen, his union

with whom was not happy, in consequence of a hereditary disposition to

madness on her part, which made its appearance a few years after the

marriage, and which subsequently caused her to be put in confinement.

In 1770 appeared

the work which first brought Dr. Beattie prominently into notice, viz, ‘An

Essay on the Nature and Immutability of Truth, in opposition to Sophistry

and Scepticism;’ written with the avowed purpose of confuting the pernicious

doctrines advanced by Hume and his supporters, which at that time were very

prevalent. His motives for engaging in this task are fully explained in a

long letter to Dr. Blacklock, which will be found in Forbes’ account of his

Life and Writings. The design, he says, “is to overthrow scepticism, and

establish conviction in its place, a conviction not in the least favourable

to bigotry or prejudice, far less to a persecuting spirit, but such a

conviction as produces firmness of mind, and stability of principle, in

consistence with moderation, candour, and liberal inquiry.” This work was so

popular, that in four years five large editions were sold, and it was

translated into several foreign languages. The “Essay on Truth,’ which Hume

and his friends treated as a violent personal attack, was intended to be

continued; but general ill health, and an inveterate disinclination to

severe study, prevented him from completing his design. In the same year he

published anonymously the First Book of ‘The Minstrel, or the Progress of

Genius,’ 4to, which he had commences writing in 1766. This poem was at once

highly successful. It was particularly praised by Gray the poet, who wrote

him a letter of criticism which is preserved in Forbes’ Life of Beattie.

Shortly afterwards he visited London, and was flatteringly received by Lord

Littleton, Dr. Johnson, and other ornaments of the literary society of the

metropolis. In 1773 he renewed his visit; and owing to the most powerful

influence exerted on his behalf, he obtained a pension of £200 a-year, on

account of his ‘Essay on Truth.’ George III. received him with distinguished

favour, and honoured him with an hour’s interview in the royal closet, when

the queen also was present. Among other marks of respect, the university of

Oxford conferred on him the degree of LL.D. at the same time with Sir Joshua

Reynolds. That great artist having requested him to sit for his portrait,

presented him with the celebrated painting containing the allegorical

Triumph of Truth over Sophistry, Scepticism, and Infidelity. He was also

pressed to enter the Church of England by the Archbishop of York and the

bishop of London, which he declined, on the ground chiefly lest the

opponents of revealed religion should assert that he was actuated by motives

of self-interest. One prelate offered him a living worth nearly £500 a-year;

which also he refused, “partly,” he says, “because it might be construed

into a want of principle, if, at the age of 38, I were to quit, with no

other apparent motive than that of bettering my circumstances, that

church of which I have hitherto been a member.” In 1774 appeared the Second

Book of the ‘Minstrel,’ which has become one of the standard poems in our

language. A vacancy having occurred in the chair of natural and experimental

philosophy in Edinburgh, he was advised by several of his friends to become

a candidate; but this he declined, preferring to remain in Aberdeen. In 1777

he brought out by subscription a new edition of his ‘Essay on Truth,’ to

which were added some miscellaneous dissertations on “Poetry and Music,’

“Laughter and Ludicrous Composition,’ and ‘The Utility of Classical

Learning.’ In 1783 he published “Dissertations, Moral and Critical,’ 4to,

and in 1786 “Evidences of the Christian Religion,’ 2 vols. 12mo. In 1790 he

edited an edition of Addison’s papers, which appeared at Edinburgh that

year. The same year he published the first volume of his “Elements of Moral

Science;’ the second followed in 1793. To the latter volume was appended

some remarks against the continuance of the slave-trade. Long before the

abolition of that iniquitous traffic was mooted in parliament. Dr. Beattie

had introduced the subject into his academical course, with the express hope

that the lessons of humanity which he taught would be useful to such of his

pupils as might thereafter proceed to the West Indies. His last production

was ‘An Account of the Life, Character, and Writings of his eldest Son,

James Hay Beattie,’ an amiable and promising young man, his assistant in the

professorship, who died in 1790, at the age of 22 (see next article). This

great affliction was followed in 1796 by the equally premature death of his

youngest son Montague, in his 19th year. These bereavements, with

the melancholy fate of his wife, quite broke his heart. Looking at the

corpse of his boy, he said, “I am now done with this world;” and although he

performed the duties of his chair till a short time previous to his death,

he never again applied to study; he enjoyed no society or amusement; even

music, of which he had been passionately fond, lost its charms for him, and

he answered few letters from his friends. Yet ye would sometimes express

resignation to his childless condition. “How could I have borne,” he would

feelingly say, “to see their elegant minds mangled with madness!” He had

been all his life subject to headaches, which sometimes interrupted his

studies; but now his spirits and his constitution were entirely gone. – In

April 1799 he was struck with palsy, and, after some paralytic strokes, he

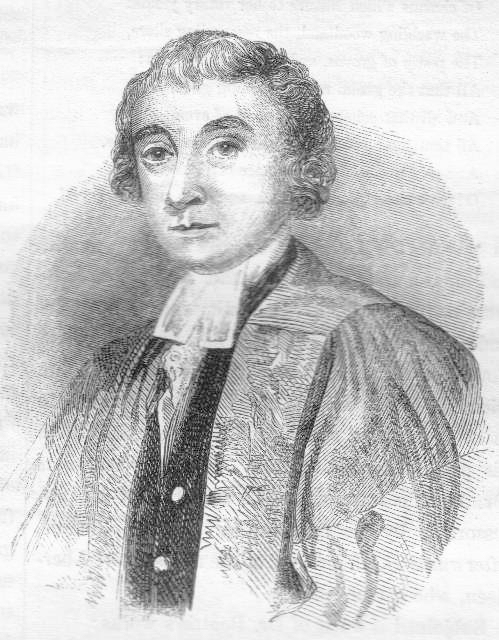

died at Aberdeen, August 18, 1803. Subjoined is a portrait of Dr. Beattie

from the painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds:

Dr.

Beattie’s metaphysical writings are clear, lively, and attractive, but not

profound, and the “Essay on Truth,’ once so much read and admired, has now

fallen into comparative neglect, from its merits having been much overrated

at the time it appeared. His poem of the “Minstrel,’ his ‘Odes to Retirement

and Hope,’ and his ‘Hermit,’ will perpetuate his name as one of the most

popular and pleasing poets of the eighteenth century, when his philosophical

productions are no longer read. “Of all his poetical works,” says Sir

William Forbes, “the Minstrel is beyond all question the best, whether we

consider the plan or the execution. The language is extremely elegant, the

versification harmonious; it exhibits the richest poetic imagery, with a

delightful flow of the most sublime, delicate, and pathetic sentiment. It

breathes the spirit of the purest virtue, the soundest philosophy, and the

most exquisite taste. In a word, it is at once highly conceived and

admirably finished.” The descriptions of natural scenery in this fine poem

are not exceeded in beauty by those of any of his contemporaries. The

following stanza was declared by Gray to be “true poetry:”

O! How can’st thou renounce the boundless store

Of charms which Nature to her votary yields?

The warbling woodland, the resounding shore,

The pomp of groves, and garniture of fields;

All that the genial ray of morning gilds,

And all that echoes to the song of even,

All that the mountain’s sheltering bosom shields,

And all the dread magnificence of Heaven;

O! How canst thou renounce, and hope to be forgiven!

In

private life Dr. Beattie was a man of amiable and unassuming manners; and a

warm attachment to the principles of morality and religion pervades all his

writings. His life, by Sir William Forbes of Pitsligo, baronet, an old and

intimate friend of his, which appeared in two volumes 4to in 1806, contains

some interesting selections from his private correspondence. In his latter

years Dr. Beattie was assisted in the duties of his professorship by his

relation, Mr. George Glennie, afterwards D.D., and one of the ministers of

Aberdeen, who succeeded him.

Subjoined

is a list of Dr. Beattie’s works:

Original Poems and Translations. Lond. and Edin. 1761. Consisting partly of

originals, and partly of pieces formerly printed in the Scots Magazine.

The

Judgment of Paris; a Poem. 1765, 8vo.

A

new edition of his Poems. Second edition. 1766, 8vo. To this edition he

added a Poem of the Talk of Erecting a Monument to Churchill, in

Westminster-Hall, and by Sir William Forbes, to have been first published

separately, and without a name.

Essay on the Nature and Immutability of Truth, in opposition to Sophistry

and Scepticism. 1770, 8vo. Edin. 1771, 8vo. 1772, 1773. Lond. 1774, 8vo.

1776.

The

Minstrel, or the Progress of Genius; a Poem. Book i. Edin. 1771, 4to. Book

ii. Edin. 1774, 4to. Published together, with a few juvenile poems. 1777, 2

vols. 12mo. Edin. 1803, 4to. A new edition, with the Life of the Author by

Alex. Chalmers, Esq. 1805, 8vo. Book iii, being a continuation of the

Minstrel, appeared in1807, 4to.

Essays on Poetry and Music, as they affect the mind; on Laughter and

Ludicrous Composition; on the Utility of Classical Learning. Edin. 1776,

8vo. Loun. 1779, 8vo.

Dissertations, Moral and Critical, on Memory and Imagination; on Dreaming;

the Theory of Language; on Fable and Romance; on the Attachments of Kindred;

and Illustrations on Sublimity. Lond. 1783, 4to.

Evidences of the Christian Religion briefly and plainly stated. Lond. 1786,

2 vols, 8vo.

The

Theory of Language; in two parts.

Elements of Moral Science. Vol. i. 1790, 8vo; including Psychology, or

Perceptive Faculties and Active Powers; and Natural Theology; with two

Appendices on the Incorporeal Nature, and on the Immortality of the Soul.

Second volume. Lond. 1793, 8vo. Containing Ethics, Economics. Politics, and

Logic.

Remarks on some Passages on the Sixth Book of the Æneid. Trans. Roy. Soc.

Edin. 1790, 2d vol. This is, in fact, a dissertation on the Mythology of the

Romans, as poetically described by Virgil, in the episode of the descent of

Æneas into hell.

BEATTIE,

JAMES HAY,

son of the preceding, was born at Aberdeen, November 6, 1768. “He had

reached his fifth or sixth year,” says his father, “knew the alphabet, and

could read a little; but had received no particular information with respect

to the Author of his being; because I thought he could not yet understand

such information; and because I had learnt from my own experience, that to

be made to repeat words not understood, is extremely detrimental to the

faculties of a young mind. In a corner of a little garden, without informing

any person of the circumstance, I wrote in the mould with my finger the

three initial letters of his name; and sowing garden cresses in the furrows,

covered up the seed, and smoothed the ground. Ten days after, he came

running up to me, and with astonishment in his countenance, told me that his

name was growing in the garden. I smiled at the report, and seemed inclined

to disregard it; but he insisted on my going to see what had happened. Yes,

said I, carelessly, I see it is so; but there is nothing in this worth

notice; it is mere chance, and I went away. He followed me, and taking hold

of my coat, said, with some earnestness, It could not be mere chance, for

somebody must have contrived matters to as to produce it. So you think, I

said, that what appears so regular as the letters of your name cannot be by

chance? Yes, said he, with firmness, I think so. Look at yourself, I

replied, and consider your hand and fingers, your legs and feet, and other

limbs; are they not regular in their appearance, and useful to you? He said

they were. Came you, then, hither, said I, by chance? No, he answered, that

cannot be; something must have made me. And who is that something? I asked.

He said, he did not know. I had now gained the point I aimed at, and saw

that his reason taught him, though he could not so express it, that what

begins to be must have a cause, and that what is formed with regularity must

have an intelligent cause. I therefore told him the name of the Great Being

who made him and all the world; concerning whose adorable nature I gave him

such information as I thought he could in some measure comprehend. The

lesson affected him greatly, and he never forgot either it or the

circumstance that introduced it.” The first rules of morality taught him by

his father were to speak truth and keep a secret, and “I never found,” he

says, “that in a single instance he transgressed either.” Having received

the rudiments of his education at the grammar school of Aberdeen, he was

entered at the age of 13, a student in the Marischal College, and was

admitted to the degree of M.A. in 1786. In June 1787 when he was not quite

nineteen, on the recommendation of the Senatus Academicus of Marischal

College, he was appointed by the king assistant professor and successor to

his father in the chair of moral philosophy and logic. In this character, it

is stated, he gave universal satisfaction, though so young. He was so deeply

impressed with the importance of religion, as always to carry about with him

a pocket Bible and the Greek New Testament. He studied music as a science,

and performed well on the organ and violin, and contrived to build an organ

for himself. He early began to write poetry, and had he been spared, he

would no doubt have produced something worthy of his name. But his days were

numbered. In the night of the 30th November 1789, he was suddenly

seized with fever; before morning a perspiration ensued, which freed him

from all immediate danger, but left him weak and languid. Though he lived

for a year thereafter, his health rapidly declined, and he was never again

able to engage much in study. He died November 19, 1790, in the 22d year of

his age. Over his grave, in the churchyard of St. Nicholas, Aberdeen, his

afflicted father erected a monument to his memory, and, as already stated in

the life of Dr. Beattie, his writings in prose and verse were published by

the latter in 1799, with a memoir of the author. “His life,” says Dr.

Beattie in a letter to the Duchess of Gordon, giving an account of his

death, “was one uninterrupted exercise of piety, benevolence, filial

affection, and indeed every virtue which it was in his power to practise.”

He was an excellent classical scholar, and his talents were considered of

the highest order by all who had an opportunity of knowing him.

BEATTIE,

GEORGE,

author of ‘John o’Arnha’,’ was born in the parish of St. Cyrus, county of

Kincardine in 1785. His parents were respectable, and he received a liberal

education. In 1807 he commenced business as a writer in Montrose. His

abilities soon brought him into notice. He had a strong turn for poetry,

some pieces of which have been published. In September 1823 a disappointment

in love brought on a depression of spirits, under the influence of which he

deprived himself of life, in the church-yard of St. Cyrus, where a tombstone

has been erected to his memory, with an appropriate inscription. The fifth

edition of ‘John o’Arnha’,’ a humorous and satirical poem, somewhat in the

style of ‘Tam o’Shanter,’ appeared at Montrose in 1826, to which was added

‘The Murderit Mynstrell,’ and other poems. The opening lines of ‘The

Murderit Mynstrell,’ which is in the old Scottish dialect, are very fine; –

How

sweitlie shonne the morning sunne

Upon the bonnie Ha’-house o’Dun:

Siccan a bien and lovelie abode

Micht syle the pilgrime aff his roade;

But the awneris’ hearte was harde as stane,

And his Ladye’s was harder still, I weene.

They neur gaue amous to the poore,

And they turnit the wretchit frae thair doure;

Quhile the strainger, as he passit thair yett,

Was by the wardowre and tykkes besett.

Oh! There livit there ame bonnie Maye,

Mylde and sweit as the morning raye,

Or the gloamin of ane summeris daye;

Hir haire was faire, hir eyne were blue,

And the dymples o’luve playit round hir sweit mou;

Hir waiste was sae jimp, hir anckel sae sma,

Hir bosome as quhyte as the new-driven snawe

Sprent o’er the twinne mountains of sweit Caterhunne,

Beamand mylde in the rayes of a wynterie sunne.

Quhair the myde of a fute has niver bein,

And not a cloud in the life is sein;

Quhen the wynd is slamb’ring in its cave,

And the barke is sleeping on the wave,

And the breast of the ocean is as still

As the morning mist upon Morven Hill.

Oh sair did scho rue, baith nighte and daye,

Hir hap was to be this Ladye’s Maye.

|