BALIOL, or BALLIOL,

the name of a Norman baron, whose descendant was

declared king of Scotland in 1292. He was possessor of

Balleul, Harcourt, and other manors in Normandy, from

the former of which he derived his name. His son, Guy

de Baliol, came over to England with the Conqueror’s

son, William Rufus, who appointed him lord of the

forest of Teesdale and Marwood, and bestowed on him

the lands of Middleton and Biwell in Northumberland.

He had also lands in Yorkshire. His son, Bernard de

Baliol, built the strong castle on the Tees, in the

county of Durham, called Bernard Castle, and was

forced by David the First of Scotland, in 1135, to

swear fidelity to Matilda. Previous to the battle of

the Standard, in 1138, the English sent Robert de

Bruce and Bernard de Baliol to the Scottish army under

David the First, to endeavour to procure peace, but

the proposal was rejected with disdain, when Bruce

renounced the homage which he had performed to David

for a barony in Galloway, and Baliol also gave up the

fealty, sworn to Matilda three years before. Adhering

to the fortunes of King Stephen, Baliol was taken

prisoner at the battle of Lincoln, with that monarch,

2d February 1141. On the incursion into Northumberland

of the Scots in 1174, he was among the Yorkshire

barons who, with Robert de Stutteville, hastened to

the relief of Alnwick castle, then besieged by the

Scottish king. During their hurried march a dense fog

arose, and the more cautious advised a retreat, when

Baliol exclaimed, "You may retreat, but I

will go forward alone, and preserve my honour." In

consequence they all advanced, and the returning light

enabled them to descry the battlements of Alnwick

castle. William, the Scottish king, was then in the

fields with a slender train of sixty horsemen. At the

head of these, however, he instantly charged the new

comers, whose force was much larger. Being

overpowered, and unhorsed, he was made prisoner by

Baliol, and sent first to the castle of Richmond and

afterwards to Falaise in Normandy. (Hailes’ Annals,

vol. i. p. 115.) This feudal chief married Agnes

de Pinkeny. His son, Eustace de Baliol, was the father

of Hugh de Baliol, who, in 1216, was joined with

Philip de Hulcotes in defence of the northern borders,

and when Alexander the Second of Scotland had subdued

the whole of Northumberland, these two barons held out

stoutly all the fortresses upon the line of the Tees,

particularly that of Bernard castle, the seat of the

Baliol family, which was assaulted by Alexander, and

before which Eustace de Vesci, the husband of his

illegitimate sister, Margaret, was slain. Hugh de

Baliol’s eldest son, John de Baliol, was one of the

magnates of Henry the Third of England, whose cause he

strenuously supported in his struggles with his

barons. He was possessed of great wealth, having

thirty knights’ fees, equal to twelve thousand pounds

of modern money. He married Devorgilla, one of the

three daughters and co - heiresses of Allan, lord of

Galloway, by Margaret, eldest daughter of David, earl

of Huntingdon, and in right of his wife he had large

possessions in Scotland, and was one of the Regents

during the minority of Alexander III. In 1263 he laid

the foundation of one of the colleges at Oxford, which

was completed by his widow, and still bears his name.

He died in 1268. His son, John de Baliol, became

temporary king of Scotland, by the award of Edward the

First. Of this John de Baliol a notice is given below.

Alexander de Baliol, the brother of John, king

of Scots, being in the retinue of Antony Beck, the

celebrated bishop of Durham, in the expedition of

Edward the First to Flanders, was restored to all his

bother’s lands in Scotland in 1297, and on 26th

September 1300, he was summoned by writ to parliament

till the 3d November 1306, under the title of Baron

Baliol. He married Isabell, daughter and heiress of

Richard de Chilham, and widow of David de Strathbogie,

earl of Athol, by whom he obtained for life the castle

and manor of Chilliam in the county of Kent. Dying

without issue, the barony of Baliol in consequence

became extinct.

There were several collateral branches of the

name of Baliol in Scotland, whose names appear as

donors and witnesses in the cloister registers. In the

Ragman Roll, also, four or five of them are mentioned.

One of these, Alexander de Balliolo, Camerarius

Scotiae, was baron of Cavers in Teviotdale. As

chamberlain of Scotland he has a place in the Lives of

the Officers of State, (page 266.) The name of Baliol

is supposed, (Nesbit's Heraldry, vol. i. p.

178,) to have been changed to Baillie (see BAILLIE),

having become odious in Scotland.

BALIOL, JOHN,

some time king of Scotland, -was the son of John de

Baliol of Bernard castle, county of Durham, the

founder of Baliol college, Oxford, as already stated,

by his wife, the Lady Devorgilla, granddaughter of

David, earl of Huntingdon, and is supposed to have

been born about 1260. On the death, in 1290, of

Margaret the "Maiden of Norway," granddaughter of

Alexander the Third, no less than thirteen competitors

came forward for the vacant throne of Scotland. Of

these, John de Baliol and Robert de Bruce, lord of

Annandale, were the principal. Baliol claimed as being

great-grandson to the earl of Huntingdon, younger

brother of William the Lion, by his eldest daughter,

Margaret; and Bruce as grandson by his second

daughter, Isabella; that is, the former as direct

heir, and as nearest of right, and the latter as

nearest in blood and degree. According to the rules of

succession which are now established, the right of

Baliol was preferable; but the protest and appeal of

the seven earls of Scotland to Edward, brought to

light by Sir Francis Palgrave, shows that in that age

the order of succession was not ascertained with

precision, and that the prejudices of the people and

even the ancient laws of the kingdom favoured the

claims of Bruce, and to this circumstance the unhappy

results which followed may in a great measure be

attributed. The competitors agreed to refer their

claims to the arbitration of Edward the First of

England, who straightway asserted and extended his

claim of feudal superiority to an extent never

attempted by any of his predecessors. He met the

Scottish nobility and clergy at Norham on the 10th

May, 1291, and required them to recognise his title as

lord paramount. At their request he granted them a

term of three weeks in order that they might consult

together, at which period he required them to return a

definitive answer. In the meantime he had commanded

his barons to assemble at Norham with all their

forces, on the 3d June. On the 2d he gave audience to

the Scots in an open field, near Upsettlington, on the

north bank of the Tweed, opposite to the castle of

Norham, and within the territory of Scotland. At this

assembly eight of the competitors for the crown were

present, who all acknowledged Edward as lord paramount

of Scotland, and agreed to abide by his decision.

Bruce was among them, but Baliol was absent. The next

day Baliol appeared, and on being asked by the

chancellor of England whether he was willing to make

answer as the others had done, after an affected

pause, he pronounced his assent.

Edward, going beyond his mere claim as overlord

or superior of Scotland, now brought forward a right

of property in the kingdom, and demanded to be put in

possession of it, on the specious pretext that he

might deliver it to him to whom the crown was found

justly to belong. Even this strange demand was acceded

to, all the competitors agreeing that sasine of the

kingdom and its fortresses should be given to Edward.

On the 11th, therefore, the regents of Scotland made a

solemn surrender of the kingdom into Edward’s hands,

and the keepers of castles surrendered their castles.

The only demur was on the part of Gilbert de

Umfraville, earl of Angus, who would not give up the

castles of Dundee and Forfar, without a bond of

indemnification. (See ante, page 127.) Edward

immediately restored the custody of the kingdom to the

regents, Fraser, bishop of St. Andrews, Wishart,

bishop of Glasgow, John Comyn of Badenoch, and James,

the steward of Scotland. The final hearing of the

competition took place, on the 17th November 1292, in

the hall of the castle of Berwick-upon-Tweed, when

Edward confirmed the judgments of his commission and

parliament by giving judgment in his favour. On the

19th the crown was formally declared to belong to him,

and the next day he swore fealty for it to Edward at

Norham. On the 30th of the same month, Baliol was

crowned at Scone, and being immediately recalled to

England, was compelled to renew his homage to Edward

at Newcastle. In the course of a year, Baliol was four

times summoned to appear before Edward in the

parliament of England. Roused by the indignities

heaped upon him while there, he ventured to

remonstrate, and would consent to nothing which might

be construed into an acknowledgment of the

jurisdiction of the English parliament. Having, on the

23d October, 1295, concluded a treaty with Philip,

king of France, Baliol, who at times was not without

spirit, which, however, he wanted firmness to sustain,

solemnly renounced his allegiance to Edward, and

obtained the Pope’s absolution from the oaths which he

had taken. Edward received the intelligence of his

renunciation with contempt rather than with anger.

"The foolish traitor," said he to Baliol’s messenger,

"since he will not come to us, we will go to him."

With a large army he immediately marched towards

Scotland. In the meantime, a small party of Scots

crossed the borders, and plundered Northumberland and

Cumberland. They took the castle of Werk, and slew a

thousand of the English. King Edward, on the other

hand, having taken Berwick, put all the garrison and

inhabitants to the sword. The Scots army were defeated

at Dunbar, 28th April, 1296, and the castles of

Dunbar, Edinburgh, and Stirling falling into Edward’s

hands, Baliol was obliged to retire beyond the river

Tay. On July 10, 1296, in the churchyard of Stracathro,

near Montrose, in presence of Anthony Beck, bishop of

Durham and the English nobles, he surrendered his

crown and sovereignty into the hands of the English

monarch, and was divested of everything belonging to

the state and dignity of a king. He was thereafter,

with his son, sent to London, and imprisoned in the

Tower, where he remained till July 20, 1299, when, on

the intercession of the Pope, he and his son were

delivered up to his legate. "Thus ended," says Lord

Hailes, "the short and disastrous reign of John

Baliol, an ill-fated prince, censured for doing homage

to Edward, never applauded for asserting the national

independency. Yet, in his original offence he had the

example of Bruce; at his revolt he saw the rival

family combating under the banners of England. His

attempt to shake off a foreign yoke speaks him of a

high spirit, impatient of injuries. He erred in

enterprising beyond his strength; in the cause of

liberty it was a meritorious error. He confided in the

valour and unanimity of his subjects, and in the

assistance of France. The efforts of his subjects were

languid and discordant; and France beheld his ruin

with the indifference of an unconcerned spectator."

Baliol retired to his estates in France, where he died

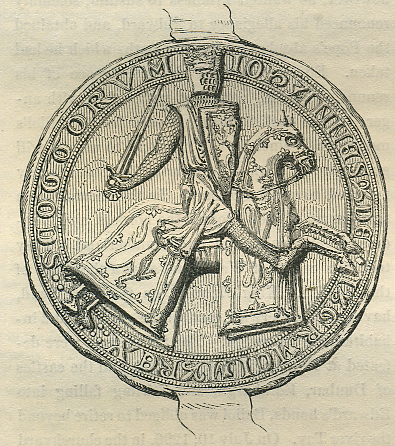

in 1314. At left is a cast

of the seal of John Baliol, while king of Scotland,

from Anderson’s Diplomata Scotiae.

During the subsequent contest in Scotland under

Wallace, the assertors of the national independence

maintained the rights of Baliol, and Wallace, so long

as he held authority, acted as governor of the kingdom

under him and in his name. To the unpopularity of the

family and of Baliol’s brother, who had taken part

with Edward, may in part be attributed the partial

support which the great patriot received in his

struggle. For the rest of his life, John Baliol

resided as a private man in France, without

interfering in the affairs of Scotland. Some writers

say that he lived till he was blind, which must have

been the effect of some disease and not of old age, as

he could not have been, at the time of his death,

above fifty-five years old at the utmost. He married

Isabel, daughter of John de Warren, earl of Surrey.

The Scots affixed the contemptuous epithet of Toom

Tabard (empty jacket) to Baliol, their temporary

king.—Dalrymple’s Annals of Scotland, vol. i.

BALIOL, EDWARD,

eldest son of the preceding, succeeded, on the death

of his father, to his estates in France, where he

resided in a private manner for several years. In 1824

he was invited over by Edward the Second of England,

to be brought forward as a rival to Robert the Bruce,

and in 1327, at the request of Edward the Third, he

again visited England with the same object. His first

active appearance on the scene was on the following

occasion: Some of the Anglo-Norman barons possessed

estates in Scotland, which were forfeited during the

war with England. By the treaty of Northampton in

1328, whereby the independence of Scotland was

secured, their estates in that country were restored

to the English barons. Two of these, Thomas Lord Wake,

and Henry de Beaumont, having in vain endeavoured to

procure possession, joined Baliol, when, after the

death of Bruce, he resolved to attempt the recovery of

what he considered his birthright. In Caxton’s

Chronicle it is stated, that in 1331, having taken the

part of an English servant of his who had killed a

Frenchman, Baliol was himself imprisoned in France,

and only released on the intercession of the Lord de

Beaumont, who advised him to come over to England, and

set up his claim to the Scottish crown. King Edward

did not openly countenance the enterprise. With three

hundred men at arms, and a few foot soldiers, Baliol

and his adherents sailed from Ravenspur on the Humber,

then a port of some importance, but overwhelmed by the

sea some centuries since, and landing at Kinghorn,

August 6, 1332, defeated the earl of Fife, who

endeavoured to oppose them. The army of Baliol,

increased to three thousand men, marched to Forteviot,

near Perth, where they encamped with the river Earn in

front. On the opposite bank lay the regent of the

kingdom, the earl of Mar, with upwards of thirty

thousand men, on Dupplin Moor. At midnight, the

English force forded the Earn, and attacking the

sleeping Scots, slew thirteen thousand of them,

including the earls of Mar and Moray. Baliol then

hastened to Perth, where he was unsuccessfully

besieged by the earl of March, whose force he

dispersed. On the 24th of September, 1332, Edward

Baliol was crowned king at Scone. On the 10th of

February 1333, he held a parliament at Edinburgh,

consisting of what are known as the disinherited

barons, with seven bishops, including both William of

Dunkeld, and it is said Maurice of Dunblane, the abbot

of Inchaffray, who there agreed to the humiliating

conditions proposed by Edward the Third. His good

fortune now forsook him. On the 16th December, within

three months after, he was surprised in his encampment

at Annan by the young earl of Moray, the second son of

Randolph, the late regent, Archibald Douglas, brother

of the good lord James, Simon Fraser, and others of

the heroes of the old war of Scotland’s independence,

and his army being overpowered, and his brother Henry,

with many of his chief adherents, slain, he escaped

nearly naked and almost alone to England. Having on

the 23d of November preceding sworn feudal service to

the English monarch, the latter marched an army across

the borders to his assistance, and the defeat of the

Scots at Halidon Hill, July 19, 1333, again enabled

Baliol to usurp for a brief space the nominal

sovereignty of Scotland. At right is a cast of the

seal of Edward Baliol from Anderson's Diplomata

Scotiae.

He now renewed his homage to Edward III., and

ceded to him the town and county of Berwick, with the

counties of Roxburgh, Selkirk, Peebles, Dumfries, and

the Lothians, in return for the aid he had rendered

him. In 1334 he was again compelled to fly to England.

In July 1335 he was restored by the arms of the

English monarch. In 1338, being by the regent, Robert

Stewart, closely pressed at Perth, where this restless

intruder, supported by the English interest, held his

nominal court, he again became a fugitive. After this

he made several attempts to be re-established on the

throne, but the nation never acknowledged him; their

allegiance being rendered to David the Second, infant

son of Robert the Bruce. At last, worn out by constant

fighting and disappointment, in 1356 he sold his claim

to the sovereignty, and his family estates, to Edward

the Third, for five thousand merks, and a yearly

pension of two thousand pounds sterling, with which he

retired into obscurity, and died childless at

Doncaster in 1363. With him ended the line of Baliol.—Tytlers’s History of Scotland.

Baliol from the Dictionary of

National Biography