BAILLIE,

a

surname supposed to have been originally the same as

Baliol. In the account of the Baillies of Lamington

inserted in the appendix to Nisbet’s Heraldry, it is

stated that Mr. Alexander Baillie of Castlecarry, a

learned antiquarian, was of opinion that the family of

Lamington were a branch of the illustrious house of the

Baliols, who were lords of Galloway, and kings of

Scotland. (See BALIOL, surname of.) An uncle of King John

Baliol, named Sir Alexander Baliol of Cavers, was great

chamberlain of Scotland in the reign of his nephew, in

1292. By Isabel, his wife, the daughter and heiress of

Richard de Chillam, the widow of David de Strath— bogie,

earl of Athol, he had two sons, Alexander and William

Baliol. Alexander the eldest, after the abdication of his

cousin, King John, joined the Scottish party, for which he

was, by order of King Edward, imprisoned in the tower of

London, but upon security given by his father and two

gentlemen of the house of Lindsay, he was enlarged. (Rymer.)

His other son, William, had the lands of Penston and

Carnbroe, in the barony of Bothwell, Lanarkshire, the

oldest of the possessions of the Baillies of Lamington.

After the abdication of his cousin, he also joined the

Scottish party, which rendered him so obnoxious to King

Edward, that by act of the parliament of England, he was,

in 1297, fined in four years’ rent of his estate. From

Robert the Bruce he got a charter of the lands of Penston.

He gave in pure alms to the monks of Newbattle

licentiam formandi stagnum in terra de Carnbrue. The

lands of Carnbroc continued in the same family till they

were given over to a younger son, the ancestor of the

Baliols or Baillies of the house of Carphin.

In the list of captives taken with David the Second at the

battle of Durham in 1346, occurs William Baillie

(Rymer), the first time that the name is found thus

written, or Englished, as it is expressed. After his

release this William Baillie was, in 1357, knighted by

David the Second, who granted him a charter, dated 27th

January 1368, of the barony of Lamington, which has

remained in the possession of his descendants till the

present time. Lamington had previously belonged to a

family of the name of Braidfoot. It is traditionally

stated that the celebrated Sir William Wallace acquired

the estate of Lamington by marrying Marion Braidfoot, the

heiress of that family, and that it passed to Sir William

Baillie on his marriage with the eldest daughter and

heiress of Wallace. The statement, however, is incorrect.

Sir William Wallace left no legitimate offspring, but his

natural daughter is said to have married Sir William

Baillie of Hoprig, the progenitor of the Baillies of

Lamington.

This Sir William Baillie of Hoprig and Lamington had two

sons, William his heir, and Alexander, who, according to

Baillie of Castlecarry, was the first of the family of

Carphin. From him descended also, besides the Baillies of

Parbroth, the Baillies of Park, Jerviston, Dunrogal,

Carnbroe, Castle-carry, and Provand. The first of the

latter family was Sir William Baillie of Provand, the

cousin of the then laird of Lamington. In 1557, he was

appointed to the then benefice of Lamington, being the

first incumbent of it after the Reformation. At that

period a certain proportion of the Lords of Council and

Session were chosen from among the clergy, and in 1566 he

was called to the bench, when he took the title of Lord

Provand. He was lord president of the court of session

from 1565 till his death in 1595. lIe left a daughter,

Elizabeth, his sole heiress, who married Sir Robert

Hamilton of Goslingtoun and Silvertonhill.

Of the house of Carphin was Mr. Cuthhert Baillie, who was

rector of Cumnock, commendator of Glenluce, and lord high

treasurer of Scotland in 1512, in the reign of James the

Fourth. (Lives of the Lord High Treasurers.)

The

eldest son of the above mentioned Sir William Baillie of

Hoprig and Lamington, is designed Willielmus Baillie of

Hoprig, in a charter from his cousin, "Joannes de

Hamilton, Dominus de Cadiow," ancestor of the dukes of

Hamilton, of the lands of Hyndshaw and Watston, dated 4th

February 1895. He married Isabella, daughter of Sir

William Seton of that ilk, ancestor of the earls of

Wintoun, by whom he had Sir William, his son and heir, who

was one of the hostages sent to England for James the

First, in exchange for David Leslie of Leslie, in 1432.

(Rymer.)

The

latter Sir William Baillie of Hoprig and Lamington,

married Catharine, daughter of the above mentioned Sir

John Hamilton of Cadzow.

His son and successor, also named Sir William Baillie, was

in 1484, one of the conservators of the peace with

England, on the part of Scotland, then concluded at

Nottingham, and in the year following he was witness to a

charter of the lands of Cambusnethan, granted by John Lord

Somerville to John Somerville, his son, by Mary Baillie

his wife, daughter of this Sir William Baillie of

Lamington. His son and brother were also witnesses to the

same charter. He had two other daughters; Margaret

married to John earl of Sutherland, and had issue, and

Marion to John Lord Lindsay of the Byres, ancestor to the

earls of Crawford.

Sir William Baillie of Hoprig and Lamington, his son, in

1492, had a charter under the great seal to him and Marion

Home his wife, in conjunct fee and infeftment. This lady

was the daughter of Sir Patrick Home of Polwarth,

comptroller of Scotland in the reign of James the Fourth,

and ancestor of the earls of Marchmont, by whom he bad Sir

William Baillie, his son and heir, and John Baillie, of

whom descended the Baillies of St. John’s Kirk,

Lanarkshire, of whom are come the Baillies of Jerviswood

and Walston.

Sir William Baillie, the eldest son, married his cousin

Elizabeth, daughter and one of the heirs of line of John

Lord Lindsay of the Byres, by whom he had Sir William his

son and heir, and a daughter, Janet, married to Sir David

Hamilton of Preston.

Sir William Baillie of Lamington, his son and successor,

was made principal master of the wardrobe to Queen Mary,

by a gift under the privy seal, 24th January 1542. He

married Janet Hamilton, daughter of James first earl of

Arran, and duke of Chatelherault, by whom he had Sir

William Baillie, his successor, and a younger son, of whom

descended the Baillies of Bagbie and Hardington, and their

cadets. His son, Sir William Baillie, was a steady

adherent of Mary, queen of Scots, and fought for her at

the battle of Langside for which he was afterwards

forfeited, He married Margaret, daughter of John Lord

Maxwell, widow of Archibald, earl of Angus, by whom he had

one daughter, Margaret, married to her cousin, Edward

Maxwell, commendator of Dundrennan, third son of Lord

Herries of Terregles, on whom and his children by his

daughter, he settled the estate, the heir of entail to

assume the name of Baillie, a special act of parliament

being procured for the purpose. Subsequently he had a son

by a Mrs. Home, whom, on his wife’s death, he married,

hoping thereby to legitimatize his son. He also

endeavoured to reduce the settlement which he had made of

his estates, so that this son, named William, might

succeed; but it being proved that he was born while his

father’s first wife was alive, he was not able to break

the settlement. The young man went over to Germany, and

entered into the service of the renowned Gustavus Adolphus,

king of Sweden, in which he attained to the rank of

major-general. When the troubles began in Scotland, in

1638, he was, with other Scotch general officers in the

Swedish service, called home by the Covenanters, to

command their army. From the minutes of the parliament

1641, it appears that he made some faint efforts to reduce

the settlement of the estate of Lamington, but in vain.

(Nesbit’s Heraldry, Appendix, vol. ii. p. 138.) He

served as lieutenant-general against the marquis of

Montrose, by whom he was defeated at Alford and Kilsyth,

in 1645. General Baillie married Janet, daughter of Sir

William Bruce of Glenhouse, by Janet his wife, daughter

and heiress of John Baillie of Letham, with whom he got

the estate of Letham, in Stirlingshire. His eldest son

James married Joanna, the daughter and heiress of entail

of the first Lord Forrester of Corstorphine, and in her

right became in 1679 second Lord Forrester. General

Baillie's second son William, married Lilies, another of

the daughters of the first Lord Forrester, by whom he had

William, who subsequently succeeded as Lord Forrester.

(See FORRESTER, lord.)

Mr. Maxwell, who assumed the name of Baillie, grandson and

heir of entail of the laird of Lamington, succeeded to the

estate on the death of Sir William Baillie, and was

knighted by James the Sixth.

Female heirs have often held this estate, but in

accordance with the entail, the name of Baillie descends

with it.

Vice-admiral Sir Thomas John Cochrane, K.C.B., son of

admiral the Hon. Sir Alexander Forrester Cochrane, G.C.B.,

9th son of the 8th earl of Dundonald, by his first wife,

Matilda Wishart Ross, daughter of Lieut.-Gen. Sir Charles

Ross of Balnagown castle, baronet, had, with other issue,

Alexander Baillie Cochrane, Esq. of Lamington, born in

November 1816, married Annabella Mary Elizabeth, daughter

of A. K. Drummond, Esq. of Cadlands, Hunts; issue, two

daughters.

BAILLIE of Jerviswoode,

the name of an ancient family, now possessors of the

earldom of Haddington. Charles, Lord Binning, eldest son

of the sixth earl of Haddington, having married Rachel,

youngest daughter and at length sole heiress of George

Baillie of Jerviswoode and Mellerstain, their second son,

the Hon. George Hamilton, on inheriting the estates of his

maternal grandfather, assumed the surname and arms of

Baillie, and died at Mellerstain, 16th April, 1797, aged

74. His eldest son, George Baillie, Esq. of Mellerstain

and Jerviswoode, was father, with other issue, of George

Baillie Hamilton, who succeeded in 1858, as tenth earl of

Haddington (see that title, and pages 177 and 179 of this

volume).

The

BAILLIES of Dochfour, Dunain,

and others of the name in Inverness-shire, are descended

from a son of the laird of Lamington, whose gallantry at

the battle of Brechin, fought on the 18th of May 1452,

between the earls of Crawford and Huntly, was rewarded by

the latter, on whose side he was, with part of the

Castle—lands of Inverness.

In

Ross-shire are the Baillies of Tarradale and Redcastle.

BAILLIE of Polkemmet,

originally Paukommot, the name of an ancient family in

Linlithgowshire. One of its modern possessors, William

Baillie, advocate, the eldest son of Thomas Baillie,

writer to the signet, was raised to the bench in 1792,

when he took the title of Lord Polkemmet. His son, Sir

William Baillie, was in 1823, created a baronet.

The surname of Baillie, in some instances, may have been

derived from the word Bailiff, or the term bailie, which

latter is in Scotland applied to a magistrate of a burgh.

BAILLIE, ROBERT,

a learned Presbyterian minister, was born at Glasgow in

1599. his father, described as a citizen, was a son of

Baillie of Jerviston, of the family of Carphin, descended

from the Baillies of Lamington, while his mother was

related to the Gibsons of Durie. He was educated at the

university of his native city, where he took the degree of

A.M. Having studied divinity, in due time he was ordained

by Archbishop Law of Glasgow. Becoming tutor to the son of

the earl of Eglinton, that nobleman presented him to the

living of Kilwinning, in Ayrshire. In 1626 he was admitted

a regent at Glasgow college. About the same time he

appears to have prosecuted the study of the oriental

languages, and was anxious to promote similar studies in

the university. In 1629 he delivered an oration In

Laudem Linguae Hebraeae. In 1633 he declined the offer

of a living in Edinburgh. The attempt of Archbishop Laud

to introduce the Common Prayer into Scotland met with his

firm opposition; and, though episcopally ordained, he

joined the presbyterians, and was in 1638 elected, by the

presbytery of Irvine, their representative at the Assembly

held at Glasgow that year. In 1639, as chaplain to Lord

Eglinton’s regiment, he was with the army of the

Covenanters, encamped on Dunse Law, under Alexander

Leslie; on which occasion he appears to have caught some

portion of the military ardour which then prevailed in the

cause of liberty and religion. "It would have done you

good," he remarks in one of his letters, "to have cast

your eyes athort our brave and rich hills as oft as I did,

with great contentment and joy; for I was there among the

rest, being chosen preacher by the gentlemen of our shire,

who came late with Lord Eglinton. I furnished to half a

dozen of good fellows, muskets and pikes, and to my boy a

broadsword. I carried myself, as the fashion was, a sword,

arid a couple of Dutch pistols at my saddle; but, I

promise, for the offence of no man, except a robber in the

way; for it was our part alone to pray and preach for the

encouragement of our countrymen, which I did to my power,

most chearfully." (Baillie's Letters, vol. i. p.

174.) He afterwards states,

"Our sojours grew in experience of arms, in courage, in

favour, daily. Every one encouraged another. The sight of

the nobles, and their beloved pastors, daily raised their

hearts. The good sermons and prayers, morning and even,

under the roof of heaven, to which their drums did call

them for bells; the remonstrances very frequent of the

goodness of their cause; of their conduct hitherto, by a

hand clearly divine; also Lesly’s skill and prudence and

fortune, made them all as resolute for battle as could be

wished. We were feared that emulation among our nobles

might have done harm, when they should be met in the

field; but such was the wisdom and authority of that old,

little, crooked soldier, that all, with an incredible

submission, from the beginning to the end, gave over

themselves to be guided by him, as if he had been great

Solyman..... . . Had you lent your ear in the morning, or

especially at even, and heard in the tents the sound of

some singing psalms, some praying, and some reading

Scripture, ye would have been refreshed. True, there was

swearing, and cursing, and brawling, in some quarters,

whereat we were grieved; but we hoped, if our camp had

been a little settled, to have gotten some way for these

misorders; for all of any fashion did regret, and all

promised to do their best endeavours for helping all

abuses. For myself, I never found my mind in better temper

than it was all that time since I came from home, till my

head was again homeward; for I was as a man who had taken

my leave from the world, and was resolved to die in that

service without return." (Ibid. p. 211.) The treaty

of Berwick, negotiated with Charles in person, produced a

temporary cessation of hostilities.

In 1640, when the Covenanters again appeared in arms,

Mr. Baillie joined them, and towards the end of that

year, he was sent to London, with other commissioners, to

prefer charges against Laud, for the innovations which

that prelate had obtruded on the Church of Scotland. He

had previously published ‘The Canterburian’s

Self-Conviction;’ and he also wrote various other

controversial pamphlets. In 1642 he was, along with Mr.

David Dickson, appointed joint professor of divinity at

Glasgow, where he took the degree of D.D., and was

employed chiefly in teaching the oriental languages, in

which he was much skilled. In January 1651, on the removal

of his colleague to the university of Edinburgh, he

obtained the sole professorship. So great was the

estimation in which he was held, that he had at one time

the choice of the divinity chair in the four Scottish

universities. In 1643 he was elected a member of the

Assembly of Divines at Westminster, an interesting account

of the proceedings at which he has given in his

Correspondence. He was a leading member of all the General

Assemblies from 1638 to 1653, excepting only those held

while he was with the divines at Westminster. In 1649 he

was sent to Holland as a commissioner from the Church, for

the purpose of inviting over Charles the Second, under the

limitations of the Covenant. After the Restoration, on the

23d January 1661, he was admitted principal of the

university of Glasgow. He was afterwards offered a

bishoprie, which he refused. When the new archbishop of

Glasgow, Andrew Fairfoul, arrived at his metropolitan

seat, he did not fail to pay his respects to the learned

principal. Baillie admits that "he preached on the Sunday,

soberly and well." "The chancellor, my noble kind

scholar," he afterwards states, "brought all in to see me

in my chamber, where I gave them sack and ale, the best of

the town. The bishop was very courteous to me. I excused

my not using of his styles, and professed my utter

difference from his way, yet behoved to intreat his favour

for our affairs of the college, wherein he promised

liberally. What he will perform time will try."

(Letters, vol. ii. p. 461.) According to another

account, the archbishop visited him during his illness,

and was accosted in the following terms: "Mr. Andrew, I

will not call you my lord, King Charles would have made me

one of these lords; but I do not find in the New

Testament that Christ has any lords in his house." In

other respects he is said to have treated the prelate very

courteously. Mr. Baillie died in July 1662, at the age of

sixty-three. He was the author of several publications, in

Latin and English, one of which, entitled ‘Opus Historicum

et Chronologicum,’ published at Amsterdam in 1663, and

reprinted in 1668, is mentioned in terms of praise by

Spottiswood. Excerpts from his ‘Letters and Journals,’ in

2 volumes octavo, were published at Edinburgh in 1755.

These contain some valuable and curious details of the

history of those times. The Letters and Journals

themselves are preserved entire in the archives of the

Church of Scotland, and in the university of Glasgow. Many

of these letters are addressed to the author’s

cousin-german, William Spang, minister of the Scottish

staple at Campvere, and afterwards of the English

congregation at Middelburg in Zeeland. Mr. Baillie

understood no fewer than thirteen languages, among which

were Hebrew, Chaldee, Syriac, Samaritan, Arabic, and

Ethiopic.

Mr.

Baillie was twice married. His first wife was Lilias

Fleming, of the family of Cardarroch, in the parish of

Cadder, near Glasgow. Of this marriage there were several

children, but only five survived him. His eldest son,

Henry, studied for the church, but never got a living, His

posterity inherited the estate of Carnbroe, which some

years ago was sold by General Baillie. The first wife died

in June 1653, and in October 1656, he married Mrs. Wilkie,

a widow, the daughter of Dr. Strang, the former principal

of Glasgow university. By this lady he had a daughter,

Margaret, who became the wife of Walkinshaw of

Barrowfield, and grandmother of the celebrated Henry Home,

Lord Kames. Miss Clementina Walkinshaw, the mistress of

Prince Charles Stuart, was also a descendant of Mr.

Baillie’s daughter.

Mr. Wodrow extols Baillie as a prodigy of erudition, and

commends his Latin style as suitable to the Augustan age.

In foreign countries, says Irving, he appears to have

enjoyed some degree of celebrity, and is mentioned by

Saldenus as a chronologer of established reputation.

Although amiable and modest in private life, in his

controversial writings he displayed much of the

characteristic violence of the times.

The following is a list of Mr. Baillie’s works:

Operis

Historici et Chronologici libri duo, cum Tribus Diatribus

Theologicis. 1. De Haereticorum Autocatacrisi. 2.

An

Quicquid in Deo eat, Dens sit. 3. De Praedestinatione.

Amst.

1663, fol. These three Dissertations printed separately.

Amst.

1664, 8vo.

A

Defence of the Reformation of the Church of &otland,

against Mr. Maxwell, Bishop of Ross.

An

Antidote against Arminianism. Lond. 1641, 8vo. 1652, 8vo.

The

Unlawfulness and Danger of a Limited Prelacie and

Episcopacie. Lond. 1641, 4to.

A

Parallel or briefe comparison of the Liturgie with the

Masse-Book, the Brevisrie, the Ceremoniall, and other

Roish Ritualls. Loud. 1641, 1642, 1646, 1661, 4to.

Queries anent the Service Booke.

A

Treatise on Scotch Episcopacy.

Ladensium Awnszavazeaf;, the Canterburian’s Self-Con

viction; or an evident Demonstration of the avowed

Arminianisme, Poperie, and Tyrannie of that Faction, by

their owne confessions: with a Postscript to the Personat

Jesuite, Lysimachus Nicanor. Loud. 1641. 4to.

Satan

the Leader in chief to all who resist the Reparation of

Sion; as it was cleared in a Sermon to the Honourable

House of Commons at their late Solemn Fast, Febr. 28,

1643, 4to.

Errours and Induration are the great sins and the great

Judgments of the time; preached in a Sermon before the

Right Honourable the House of Peers in the Abbey Church at

Westminster, July 30, 1645, the day of the monthely Fast.

Lond. 1645, 4to.

An

Historical Vindication of the Government of the Church of

Scotland, from the manifold base Calumnies which the most

malignant of the Prelats did invent of old, and now lately

have been published with great industry in two pamphlets

at London; the one intituled Issachara Burden, &c. written

and published at Oxford by John Maxwell, a Scottish

Prelate, &c. Lond. 1646, 4to.

A

Dissuasive from the Errours of the Time; wherein the

Tenets of the Principail Sects, especially of the

Indcpendents, are drawn together in one Map, &c. Lond.

1645, 4to. 1646, 4to. 1655, 4to.

Anabaptism, the true Fountaine of Independency, Brownisme,

Antinomy, Familisme, &c. in a Second Part of the

Dissuasive from the Errours of the Time. Lond. 1647, 4to.

A

Review of Dr. Bramble, late Bishop of Londonderry, his

Faire Warning against the Scotes Disciplin. Delf. 1649,

4to. Baillie’s Review was reprinted at Edinburgh; and

having been translated into Dutch, it was published at

Utrecht.

A

Scotch Antidote against the English Infection of

Arminianism. Lond. 1652, 12mo.

Appendix practica ad Joannis Buxtorfii Epitomen

Grammaticae Hebraeae. Edin. 1653, 8vo.

A

Reply to the Modest Inquirer. Perhaps relating to the

dispute between the Resolutioners and Protesters.

Catechesis Elenctica Errorum qui hodie vexant Ecclesiam.

Lond. 1654, 12mo.

The

Dissuasive from the Errours of the Time, Vindicated from

the Exceptions of Mr. Cotton and Mr. Tombes. Lond.

1655, 4to.

Letters and Journals, containing an Impartial Account of

Public Transactions, Civil, Ecclesiastical, and Military,

in England and Scotland, from the beginning of the Civil

Wars, in 1637, to the year 1662. With an Account of the

Author’s Life prefixed, and a Glossary annexed, by Robert

Aitken. Edin. 1775, 2 vols. 8vo. The same edited from the

author’s MS. by David Laing, Esq. Edin. 1841-2. 8 vols.

8vo.

BAILLIE, ROBERT,

of Jerviswood, a distinguished patriot of the reign of

Charles the Second, sometimes called the Scottish Sydney,

was the son of George Baillie of St. John’s Kirk,

Lanarkshire, a cadet of the Lamington family, who had

become proprietor of the estate of Jerviswood in the same

county. From his known attachment to the cause of civil

and religious liberty, he had long been an object of

suspicion and dislike to the tyrannical government which

then ruled in Scotland. The following circumstances first

brought upon him the persecution of the council. In June

1676, the Reverend Mr. Kirkton, a non-conformist minister,

who had married the sister of Mr. Baillie, was illegally

arrested on the High Street of Edinburgh by one Carstairs,

an informer employed by Archbishop Sharp; and, not having

a warrant, he endeavoured to extort money from his

prisoner before he would let him go. Baillie being sent

for by his brother-in-law, hastened to his relief, and

succeeded in rescuing him. Kirkton had been inveigled by

Carstairs into a mean-looking house near the common

prison, and on Mr. Baillie with several other persons

coining to the house, they found the door locked in the

inside. Baillie called to Carstairs to open, when Kirkton,

encouraged by the voices of friends, desired Carstair’s,

who after his capture had in vain attempted to procure a

warrant, either to set him free, or to produce a warrant

for his detention. Instead of complying with either

request, Carstairs drew a pocket pistol and a struggle

ensued between Kirkton and him for its possession. Those

without hearing the noise and cries of murder, burst open

the door, and found Kirkton on the floor and Carstairs

sitting on him. Mr. Baillie drew his sword, and commanded

him to rise, asking at the same time if he had any warrant

to apprehend Mr. Kirkton. Carstairs said he had a warrant

for conducting him to prison, but he refused to produce

it, saying he was not bound to show it. Mr. Baillie

declared that if he saw any warrant against his friend, he

would assist in carrying it into execution. He offered no

violence whatever to Car-stairs, but only threatened to

sue him for the illegal arrest of his brother-in-law. He

then, with Mr. Kirkton and his friends, left the house.

Upon the complaint of Carstairs, who had procured an

antedated warrant, signed by nine of the privy council,

Mr. Baillie was called before the council, and by the

influence of Sharp fined in six thousand merks, (£318;

Wodrow says the fine was £500 sterling;) to be imprisoned

till paid. After being four months in he was liberated, on

payment of half the fine to Carstairs. The above mentioned

Mr. Kirkton wrote a memoir of the church during his own

times, from which Wodrow the historian derived much

valuable assistance.

In the year 1683, seeing no prospect of relief from the

tyranny of the government at home, Mr. Baillie and some

other gentlemen commenced a negotiation with the patentees

of South Carolina, with the vIew of emigrating with their

families to that colony; in this following the example of

Cromwell, Hampden, and others previous to the commencement

of the Civil wars; but in both instances the attempt was

frustrated, and in Mr. Baillie’s case fatally for himself.

About the same time that this negotiation was begun, he

and several of his co-patriots had entered into a

correspondence with the heads of the Protestant party in

England; and, on the invitation of the latter, he and five

others repaired to London, to consult with the duke of

Monmouth, Sydney, Russell, and their friends, as to the

plans to be adopted to obtain a change of measures in the

government. On the discovery of the Rye-House Plot, with

which he had no connection, Mr. Baillie and several of his

friends were arrested, and sent down to be tried in

Scotland. The hope of a pardon being held out to him, on

condition of his giving the government some information,

he replied, " They who can make such a proposal to me,

neither know me nor my country." Lord John

Russell observes. " It is to the honour of Scotland, that

if witnesses came forward voluntarily to accuse their

associates, as had been done in England." He had married,

early in life, a sister of Sir Archibald Johnston of

Warriston, who was executed in June, 1633, and during his

confinement previous to trial, Mr. Baillie was not

permitted to have the society of his lady, although she

offered to go into irons, as an assurance against any

attempt of facilitating his escape. He was accused of

having entered into a conspiracy to raise rebellion, and

of being concerned in the Rye-House Plot. As his

prosecutors could find no evidence against him, he was

ordered to free himself by oath, which he refused, and was

in consequence fined six thousand pounds sterling. His

persecutors were not satisfied even with this, for he was

still kept shut up in prison, and denied all attendance

and assistance, which had such an effect upon his health,

as to reduce him almost to the last extremity. Bishop

Burnet, in his History of his own Times,' tells us that

the ministers of state were most earnestly set on

Baillie's destruction, though he was now in so languishing

a condition, that if his death would have satisfied the

malice of the court, it seemed to be very near. He adds,

that "all the while he was in prison, he seemed so

composed and cheerful, that his behaviour looked like the

reviving of the spirit of the noblest of the old Greeks or

Romans, or rather of the primitive Christians, and first

martyrs in those best days of the church."

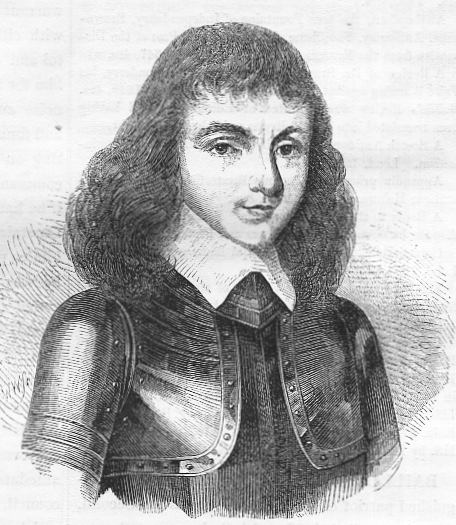

The woodcut at right is taken from an early portrait of

Mr. Baillie, painted in 1660. The original miniature is in

possession of George Baillie, Esq., of Jerviswood and

Mellerstain.

On the 23d December 1684 Mr. Baillie was arraigned

before the high court of justiciary on the capital charge,

when he appeared in a dying condition. He was carried to

the bar in his nightgown, attended by his sister, the wife

of Mr. Ker of Graden, who sustained him with cordials ;

and not being able to stand he was obliged to sit. He

solemnly denied having been accessary to any conspiracy

against the king's or his brother's life, or of being an

enemy to the monarchy. Every expedient being resorted to,

to insure his conviction, he was found guilty on the

morning of December 24th, and condemned to be hanged that

afternoon at the market-cross of Edinburgh, his head to be

fixed on the Netherbow Port, and his body to be quartered,

the quarters to be exhibited on the gaols of Jedburgh,

Lanark, Ayr, and Glasgow. On hearing his sentence he said,

"My lords, the time is short, the sentence is sharp, but I

thank my God who hath made me as fit to die as you are to

live." He was attended to the scaffold by his faithful and

affectionate sister. He was so weak that he required to be

assisted in mounting the ladder. As soon as he was up he

said, "My faint zeal for the Protestant religion hath

brought me to this ;" but the drums interrupted him. He

had prepared a speech to be delivered on the scaffold, but

was prevented. "Thus," says Bishop Burnet, "a learned and

worthy gentleman, after twenty months' hard usage, was

brought to such a death, in a way so full, in all the

steps of it, of the spirit and practice of the courts of

the Inquisition, that one is tempted to think that the

methods taken in it were suggested by one well studied, if

not practised in them." Dr. Owen, who was acquainted with

Baillie, writing to a friend in Scotland before his death,

said of him, "You have truly men of great spirit among you

; there is, for a gentleman, Mr. Baillie of Jerviswood, a

person of the greatest abilities I ever almost met with."

Mr. Baillie's family was for the time completely ruined by

his forfeiture. His son George, after his execution, was

obliged to take refuge in Holland. He afterwards returned

with the prince of Orange, in 1688, when he was restored

to his estates. He married Grizel, the daughter of Sir

Patrick Hume of Polwarth.

George Baillie, Esq. of Jerviswoode and Mellerstain, (born

in 1763, died in 1841,) nephew of the seventh earl of

Haddington, had issue, 1. George Baillie Hamilton, who

succeeded his cousin as tenth earl of Haddington, (see

page 174 of this volume ;) 2. Eliza, born in 1803, married

the second marquis of Breadalbane ; 3. Charles Baillie,

born in 1804, lord-advocate 1858, a lord of session 1859,

under the title of Lord Jerviswoode, married, with issue ;

4. Robert, major in the army ; 5. Rev. John, a canon of

York ; 6. Captain Thomas, R.N. ; 7. Mary, married George

John James, Lord Haddo, eldest son of George, fourth earl

of Aberdeen, with issue; 8. Georgina, married in 1835,

Lord Polwarth, with issue, died in 1859 ; 9. Catherine

Charlotte, married in 1840, fourth earl of Ashburnham,

with issue; 10. Grisel, born in 1822.

Evan Baillie, an eminent merchant of Bristol, born

in Inverness-shire in 1742, died at Dochfour in that

county, in June 1835, left two sons, Colonel Hugh Baillie

of Redcastle and Tarradale, Ross-shire, and James Evan

Baillie, Esq. of Culduthel and Glenelg.

BAILLIE, JOHN, of Leys,

a distinguished East Indian officer, born in

Inverness-shire in 1773, appointed a cadet on the Bengal

establishment in 1790. He received the commission of

ensign in March 1793, and of lieutenant in November 1794.

In 1797 he was employed by Lord Teignmouth to translate

from the Arabic language an important work on the

Mohammedan law, compiled by Sir William Jones. On the

first formation of the college of Fort-William, about

1800, he was appointed professor of the Arabic and Persian

languages, and of the Mohammedan law in that institution.

Soon after the commencement of the war with the

confederated Mahratta chieftains in 1803, he offered his

services as a volunteer in the field, and proceeded to

join the army then employed in the siege of Agra. His

captain's commission is dated 30th September 1803. The

precarious situation of affairs in the province of

Bundlecund requiring the superintendence of an officer,

qualified to conduct various important and difficult

negotiations, on which depended the establishment of the

British authority in that province, he was appointed by

the commander-in-chief to the arduous and responsible

office of political agent. It was necessary to occupy a

considerable tract of hostile country, in the name of the

Peishwa ; to suppress a combination of refractory chiefs,

and to conciliate others ; to superintend the operations,

both of the British troops and of their native auxiliaries

; and to establish the British civil power and the

collection of revenue, in this province, which was not

only menaced with foreign invasion, but disturbed with

internal commotion. All these objects were, by the zeal

and activity of Captain Baillie, accomplished within three

months. In a letter to the court of directors, it was

stated as the opinion of the governor-general in council,

that on occasion of the invasion of the province by the

troops of Ameer Khan, in May and June 1804, " the British

authority in Bundlecund was alone preserved by his

fortitude, ability, and influence." His services were

continued in the capacity of a member of the commission

appointed in July 1804, for the administration of the

affairs of Bundlecund; and excepting the short interval of

the last five months of 1805, which he spent at the

presidency, he continued engaged in this important service

until the summer of 1807. He thus effected the peaceable

transfer to the British dominions of a territory yielding

an annual revenue of eighteen lacs of rupees, (£225,000

sterling,) with the sacrifice only of a jaghire, of little

more than one lac of rupees per annum. In July 1807, on

the death of Colonel Collins, he was appointed resident at

Lucknow, where he remained till the end of 1815, and in

June 1818, he was placed on the retired list. He was

promoted to the rank of major in the Bengal army in

January 1811, and to that of lieutenant-colonel in July

1815. After his return to England, he was, in 1820,

elected M.P. for Hedon, for which he sat during two

parliaments, until the dissolution of 1830. In that year

he was returned for the Inverness burghs, and re-elected

in 1831 and 1832. He had been chosen a director of the

East India Company on the 28th of May 1823. He died in

London, on the 20th April 1833, aged sixty.—Annual

Obituary.

BAILLIE, MATTHEW, M.D.,

a distinguished anatomist and the first physician of his

time, was born October 27, 1761, in the manse of Shotts,

Lanarkshire, He was the son of the Rev. James Baillie, D.D.,

then minister of that parish, subsequently of Bothwell, on

the Clyde, in the same county, and afterwards professor of

divinity in the university of Glasgow, a descendant, it is

supposed, of the family of Baillie of Jerviswood. On his

mother's side he was also related to eminent individuals,

Dr. William Hunter and Mr. John Hunter, the anatomists,

being her brothers ; while his own sister was the highly

gifted and celebrated Joanna Baillie. In 1773 he was sent

to Glasgow college, where he studied for five years, and

so greatly distinguished himself, that in 1778 he was

removed, on Snell's foundation, to Baliol college, Oxford.

In 1688, Mr. John Snell, with a view to support episcopacy

in Scotland, devised to trustees the estate of Uffton,

near Leamington, in Warwickshire, for educating in that

college, Scots students from the university of Glasgow.

This fund now affords one hundred and thirty- two pounds

per annum to each of ten exhibitions, and one of these it

was young Baillie's good fortune, in consequence of his

great attainments, to secure. At the university of Oxford

he took his degrees in arts and medicine. In 1780, while

still keeping his terms at Oxford, he became the pupil of

his uncles, and when in London he resided with Dr. William

Hunter, who, childless himself, seems to have adopted him

as a son, and to have fixed upon him as his successor in

the lecture-room, in which, at this period, he sometimes

assisted. Easy in his manners, and open in his

communications, he soon became a favourite with the

students, and greatly relieved Dr. Hunter of the arduous

task of teaching in his latter years. The sudden death of

the latter, in March 1783, soon left him, in conjunction

with Mr. Cruickshank, his late uncle's assistant, to

support the reputation of the anatomical theatre, in Great

Windmill Street, which had been founded by his uncle.

[Memoirs of Eminent Physicians and Surgeons. London, 1818,

p. 37.]

Dr. Baillie began his duties as an anatomical

teacher in 1784, and he continued to lecture, with the

highest reputation, till 1799. In 1787 he was elected

physician to St. George's Hospital. In 1790, having

previously taken his degree of M.D. at Oxford, he was

admitted a fellow of the Royal college of Physicians. He

was also elected a fellow of the Royal Society, to whose

Transactions he had contributed two anatomical papers. He

was also chosen president of the new medical society. The

subject of morbid anatomy seems to have early attracted

his attention, and the valuable museum of his uncle, to

which lie had so full access, opened to him an ample field

for its investigation. Before his time, no regular system

or method of arrangement had been pursued by anatomical

writers, which could render this study useful. By a nice

and accurate observation of the morbid appearances of

every part of the body, and the peculiar circumstances

which in life distinguish them, he was enabled to place in

a comprehensive and clear compass, an extensive and

valuable mass of information, before his time in a

confused and undigested state. In 1795 he published his

valuable work, which acquired for him a European fame,

entitled 'The Morbid Anatomy of some of the most important

parts of the Human Body,' which he subsequently enlarged,

and which was translated into French and German, and has

gone through innumerable editions. In 1799 be commenced

the publication of A Series of Engravings to illustrate

some parts of Morbid Anatomy,' from drawings by Mr. Clift,

the conservator of the Hunterian Museum in

Lincoln's-Inn-Fields; which splendid and useful work was

completed in 1802.

In 1800 Dr. Baillie resigned his office in St.

George's Hospital, and thenceforward devoted himself to

general practice as a physician, in which he was so

successful that he was known in one year to have received

ten thousand pounds in fees. His work on the Morbid

Anatomy of the Human Body had placed his character high as

a pathognomic physician, and every difficult case in high

life came under his review. So fixed was his reputation in

public opinion, that even his leaving London for a period

of some months at a time made no alteration in the request

for him at his return—not usually the case with the

general run of his professional brethren. Besides

publishing 'An Anatomical Description of the Gravid

Uterus,' he contributed many important papers to the

Philosophical Transactions and medical collections of the

day. Having been called in to attend the duke of

Gloucester, whose malady however proved past cure, his

mode of treatment gave so much satisfaction to the family

of his royal highness, that it is thought to have paved

the way for his being commanded to join in consultation

the court physicians, in the case of George the Third,

during his mental aberration, and he continued a principal

director of the royal treatment during the protracted

illness of the king. Amid the mingled hopes and fears

which agitated the nation for so long a time, Dr. Baillie,

from the known candour of his nature, was looked up to

with confidence as one whose opinion could be relied upon.

The air of a court, so apt to change the sentiments, and

cause the individual to turn with every political gale,

was considered incapable of bending the stubbornness of

his tried integrity; and it is even said that his opinion

differed often from that of his more politic colleagues.

[Memoirs of Eminent Physicians and Surgeons, p. 40.] His

conduct seems to have given such high satisfaction that on

the first vacancy in 1810, he was appointed one of the

physicians to the king, with the offer of a baronetcy,

which he declined.

Dr. Baillie died on 23d September 1823, leaving to

the London College of Physicians the whole of his

extensive and valuable collection of preparations, with

six hundred pounds to keep it in order. He had married

early in life Sophia, sister of Lord Denman, late lord

chief justice of the court of Queen's Bench, by whom he

had one son and one daughter. His estate of Duntisbourne

in Gloucestershire went to his son. He left large sums to

medical institutions and public charities. While yet a

young man, his uncle William having had an unfortunate

misunderstanding with his brother John Hunter, left at his

death the small family estate of Longcalderwood in

Lanarkshire, to his nephew, in prejudice of his own

brother, to whom Dr. Baillie restored it, as being of

right his surviving uncle's.

The portrait of Dr. Baillie (left) is from a rare print.

The leading features of Dr. Baillie's character were

openness and candour. He never flattered the prejudices of

his patients, or pretended to a knowledge which he did not

possess. He knew well the ravages and consequences of

disease, and how difficult it is to rectify derangements

of structure when once permanently formed. In money

matters his liberality was remarkable. He has often been

known to return fees where he conceived the patient could

not afford them, and also to refuse a larger sum than what

he considered was his due.

Shortly after his death an elegant tribute to his

memory was delivered to the students of anatomy and

surgery in Great Windmill Street, London, by his eminent

successor in that lecture-school, Sir Charles Bell: " You,

who are just entering on your studies," he said, " cannot

be aware of the importance of one man to the character of

a profession, the members of which extend over the

civilized world. You cannot yet estimate the thousand

chances there are against a man rising to the degree of

eminence which Dr. Baillie attained; nor know how slender

the hope of seeing his place supplied in our day. It was

under this roof that Dr. Baillie formed himself, and here

the profession learned to appreciate him. He had no desire

to get rid of the national peculiarities of language; or,

if he had, he did not perfectly succeed. Not only did the

language of his native land linger on his tongue, but its

recollections clung to his heart; and to the last, amidst

the splendour of his professional life, and the seductions

of a court, he took a hearty interest in the happiness and

the eminence of his original country. But there was a

native sense and strength of mind which more than

compensated for the want of the polish and purity of

English pronunciation. He possessed the valuable talent of

making an abstruse and difficult subject plain; his

prelections were remarkable for that lucid order and

clearness of expression which proceed from a perfect

conception of the subject; and he never permitted any

vanity of display to turn him from his great object of

conveying information in the simplest and most

intelligible way, and so as to be most useful to his

pupils. It is to be regretted that his associate in the

lectureship made his duties here unpleasant to him, and I

have his own authority for saying that, but for this, he

would have continued to lecture for some years longer. Dr.

Baillie presented his collection of morbid specimens to

the College of Physicians, with a sum of money to be

expended in keeping them in order, and it is rather

remarkable that Dr. Hunter, his brother, and his nephew,

should have left to their country such noble memorials as

these. In the college of Glasgow may be seen the princely

collection of Dr. Hunter; the college of surgeons have

assumed new dignity, surrounded by the collection of Mr.

Hunter—more like the successive works of many men enjoying

royal patronage or national support, than the work of a

private surgeon; and lastly, Dr. Baillie has given to the

College of Physicians, at least, that foundation for a

museum of morbid anatomy, which we hope to see completed

by the activity of the members of that body. Dr. Baillie's

success was creditable to the time. It may be said of him,

as it was said of his uncle John, every time I hear of his

increasing eminence it appears to me like the fulfilling

of poetical justice, so well has he deserved success by

his labours for the advantage of humanity.' Yet I cannot

say that there was not in his manner sufficient reason for

his popularity. Those who have introduced him to families

from the country must have observed in them a degree of

surprise on first meeting the physician of the court.

There was no assumption of character or warmth of interest

exhibited. He appeared what he really was—one come to be a

dispassionate observer, and to do that duty for which he

was called. But then, when he had to deliver his opinion,

and more especially when he had to communicate with the

family, there was a clearness in his statement, a

reasonableness in all he said, and a convincing simplicity

in his manner that had the most soothing and happy

influence on minds, excited and almost irritated by

suffering and the apprehension of impending misfortune.

After so many years spent in the cultivation of the most

severe science—for surely anatomy and pathology may be so

considered—and in the performance of professional duties

on the largest scale, —for he was consulted not only by

those who personally knew him, but by individuals of all

nations,—he had, of late years, betaken himself to other

studies, as a pastime and recreation. He attended more to

the general progress of science. He took particular

pleasure in mineralogy; and even from the natural history

of the articles of the Pharmacopoeia he appears to have

derived a new source of gratification. By a certain

difficulty which he put in the way of those who wished to

consult him, and by seeing them only in company with other

medical attendants, he procured for himself, in the latter

part of his life, that leisure which his health required,

and which suited the maturity of his reputation; while he

intentionally left the field of practice open to new

aspirants. When you add to what I have said of the

celebrity of the uncles William and John Hunter, the

example of Dr. Baillie, and farther consider the eminence

of his sister Joanna Baillie, excelled by none of her sex

in any age, you must conclude with me that the family has

exhibited a singular extent and variety of talent. Dr.

Baillie's age was not great, if measured by length of

years; he had not completed his sixty-third year, but his

life was long in usefulness. lie lived long enough to

complete the model of a professional life. In the studies

of youth; in the serious and manly occupations of the

middle period of life; in the upright, humane, and

honourable character of a physician ; and above all in

that dignified conduct which became a man mature in years

and honours, he has left a finished example to his

profession." [Annual Register for 1823.]

Dr. Baillie would never allow any likeness of

himself to be published. He sat to Hoppner for his

portrait, in order to make a present of it to his sisters,

but finding that this picture had been put into the hands

of an engraver, he interfered to prevent its being used by

him, as he exceedingly disliked the idea of seeing his

face in the print-shop windows. The engraving, however,

was already completed, and his sense of justice would not

allow him to deprive the engraver of the fruits of his

labour. He therefore purchased the copperplate, and

permitted only a few copies to be taken from it, which

were presented to friends. His collected medical works

were published in 1825, with a memoir of his life by James

Wardrop, surgeon.

The following is a list of Dr. Baillie's works :

The Morbid Anatomy of some of the most Important Parts of

the Human Body. Lond. 1793, 8vo. Appendix to the first

edition of the Morbid Anatomy. Loud. 1798, 8vo. 2d edit.

corrected and greatly enlarged. 1797, 8vo. 7th edit. 1807.

A Series of Engravings, tending to illustrate the Morbid

Anatomy of some of the most Important Parts of the Human

Body. Fascic. lx. Loud. 1799, 1802, royal 4to. 2d edit.

1812.

Anatomical Description of the Gravid Uterus.

Case of a Boy, seven years of age, who had Hydrocephalus,

in whom some of the Bones of the Skull, once firmly

united, were, in the progress of the disease, separated to

a considerable distance from each other. Med. Trans. iv.

p. 1813.

Of some Uncommon Symptoms which occurred in a Case of

Hydrocephalus Internus. Ib. p. 9.

Upon a Strong Pulsation of the Aorta, in the Epigastric

Region. Ib. p. 271.

Upon a Case of Stricture of the Rectum, produced by a

Spasmodic Contraction of the Internal and External Spineta

of the Anus. Med. Trans. v. p. 136. 1815.

Some Observations respecting the Green Jaundice. Ib. p.

143.

class=Section8>

Some Observations on a Particular Species of Purging. Ib.

p. 166.

The Want of a Pericordium in the Human Body. Trans. Med.

et Chic. p. 91. 1793.

Of Uncommon Appearances of Disease in the Blood Vessels.

Ib. p. 119.

Of a Remarkable Deviation from the Natural Structure, in

the Urinary Bladder and Organs of Generation of a Male.

Trans. Med. et Chir. p. 189. 1793.

A Case of Emphysema not proceeding from Local Injury. Ib.

p. 292.

An Account of a Case of Diabetes, with an Examination of

the Appearances after Death. Ib. p. 170. 1800.

An Account of a Singular Disease in the Great Intestines.

Ib. p. 144.

An Account of the Case of a Man who had no Evacuation in

his Bowels for nearly fifteen weeks before his death. Ib.

p. 179.

Of a Remarkable Transposition of the Viscera. Phil. Trans.

Abr. xii. 483. 1788.

Of a Particular Structure in the Human Ovarium. Ib. 535.

1789.

BAILLIE, JOANNA,

an eminent poetess and acknowledged improver of English

poetic diction, sister of Dr. Matthew Baillie, the subject

of the preceding memoir, was born in 1762. Her birthplace

was the manse of Bothwell, a parish on the banks of the

Clyde, in the Lower ward of Lanarkshire, of which her

father, the Rev. James Baillie, D.D., afterwards professor

of divinity in the university of Glasgow, was at that time

minister. She was the younger of his two daughters. Within

earshot of the rippling of the broad waters of the Clyde,

she spent her early days. That river, confined within

lofty banks, makes a fine sweep round the magnificent

ruins of Bothwell Castle, and forms the semicircular

declivity called Bothwell Bank, that " blooms so fair,"

celebrated in ancient song ; "meet nurse for a poetic

child." In the immediate vicinity is " Bothwell Brig,"

where the Covenanters were defeated in June 1679.

"Where Bothwell Bridge connects the margin steep,

And Clyde below runs silent, strong, and deep,

The hardy peasant, by oppression driven

To battle, deem'd his cause the cause of Heaven ;

Unskill'd in arms, with useless courage stood,

While gentle Monmouth grieved to shed his blood."

After her father's death, her mother, who was a daughter

of Mr. Hunter of Longcalderwood, a small estate in the

parish of East Kilbride, in the same county, went there to

reside, with her two daughters, Agnes and Joanna, but when

the latter was about twenty years of age, Mrs. Baillie

removed with them to London, to be near her son, Dr.

Mathew Baillie, and her two brothers, Dr. William Hunter

and Mr. John Hunter, the eminent anatomists. In London or

the neighbourhood Miss Baillie resided for the remainder

of her life, she and her sister having for many years kept

house together at Hampstead. The incidents of her life are

few, being confined almost exclusively to the publication

of her works. Her earliest pieces appeared anonymously.

Her name first became known by her dramas on the Passions.

The first volume was published in 1798, under the title of

‘A Series of Plays, in which it is attempted to delineate

the stronger passions of the mind, each passion being the

subject of a tragedy and a comedy.’ In a long introductory

discourse on the subject of the drama, she explains her

principal purpose to be to make each play subservient to

the development of some one particular passion. "Let," she

says, "one simple trait of the human heart, one expression

of passion, genuine and true to nature, be introduced, and

it will stand forth alone in the boldness of reality,

whilst the false and unnatural around it fades away upon

every side, like the rising exhalations of the morning."

In thus, however, restricting her dramas to the

illustration of only one passion in each, she excluded

herself from the varied range of character which is

necessary to the acting drama, and circumscribed the

proper business of the piece; hence, her dramas are more

adapted for perusal than for representation. Nevertheless,

their merits were instantly acknowledged, and a second

edition of this her first volume was called for in a few

months. In 1802, she published a second volume of her

plays. In 1804 she produced a volume of miscellaneous

dramas, and the third volume of her plays on the Passions

appeared in 1812. All these raised her name to a proud

pre-eminence in the world of literature, and she was

considered one of the most highly gifted of British

poetesses.

Like Byron, however, Miss Baillie early came under

the censure of the Edinburgh Review, but she turned a deaf

ear to its upbraidings, and halted not in the path which

she had traced out for herself, at its bidding. Byron’s

spirit was aroused, and he retaliated in the most bitter

satire in the English language; Miss Baillie placed the

unjust judgment quietly aside, and silently went on her

way rejoicing. On the appearance of her second volume of

Plays, a very unfavourable opinion was expressed of them

in the fourth number of the Edinburgh Review, namely that

for July 1803, and her theory of the unity of passion

unequivocally condemned. In the thirty-eighth number, that

for February 1812, when the third volume had appeared, the

reviewer was still more severe. Her views were styled

"narrow and peculiar," and her scheme "singularly perverse

and fantastic." Miss Bail-lie’s plan of producing twin

dramas, a tragedy and a comedy, on each of the passions,

was thoroughly disapproved of by Mr. Jeffrey, who appeared

to think that her genius was rather lyrical than dramatic.

In his estimation her dramas combined the faults of the

French and English schools, the poverty of incident and

uniformity of the one with the irregularity and homeliness

of the other, her plots were improbable, and her language

a bad imitation of that of the elder dramatists. In this

verdict the literary public have not agreed, and the

bitter feeling in which the review was written, as in the

still more memorable case of Byron, tended to defeat its

own purpose. It was well remarked by one of the impartial

critics of Miss Baillie’s writings, that in her honourable

pursuit of fame, she did not "bow the knee to the

idolatries of the day ;" but strong in the confidence of

native genius, she held her undeviating course, with

nature for her instructress and virtue for her guide.

Amongst those who, from their first appearance, had

expressed an enthusiastic admiration of her plays on the

Passions, was Mr. (afterwards Sir) Walter Scott, who, when

in London in 1806, was introduced to Miss Baillie by Mr.

Sotheby, the translator of Oberon. The acquaintance thus

begun soon ripened into affectionate intimacy, and for

many years they maintained a close epistolary

correspondence with each other. Between these two eminent

individuals, there were in fact many striking points of

resemblance. They had the same lyrical fire and

enthusiasm, the same love of legendary lore, and the same

attachment to the manners and customs, to the hills and

woods of their native Scotland. Many of Scott’s letters to

her are inserted in Lockhart’s Life of the great novelist.

During a visit which Miss Baillie paid to Scotland

in the year 1808, she resided for a week or two with Mr.

Scott at Edinburgh. While in Glasgow, previous to her

proceeding to that city, she had sought out Mr. John

Struthers, the author of the Poor Man’s Sabbath, then a

working shoemaker, a native of the parish of East

Kilbride, whom she had known in his early years. Mr.

Struthers, in the memoirs of his own life (published with

his poems in 2 vols. in 1850), thus commemorates this

event. "In the year 1808 the author had the high honour

and the singular pleasure of being visited at his own

house in the Gorbals of Glasgow by Joanna Baillie, then on

a visit to her native Scotland, who had known him so

intimately in his childhood. He has not forgotten, and

never can forget, how the sharp and clear tones of her

sweet voice thrilled through his heart, when at the outer

door she, inquiring for him, pronounced his name—far less

could he forget the divine glow of benevolent pleasure

that lighted up her thin and pale, but finely expressive

face, when, still holding him by the hand she had been

cordially shaking, she looked around his small, but clean

apartment, gazed upon his fair wife and his then lovely

children, and exclaimed that he was surely the most happy

of poets." Through Miss Baillie’s recommendation, Mr.

Scott brought Mr. Struthers’ ‘Poor Man’s Sabbath’ under

the notice of Mr. Constable, the eminent publisher, who

was induced to bring out a third edition of that excellent

poem, consisting of a thousand copies, for which he paid

the worthy author thirty pounds, with two dozen copies of

the work for himself.

In 1810, ‘The Family Legend,’ a tragedy by Miss

Baillie, founded on a Highland tradition, was brought out

at the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh. That theatre was then

under the management of Mr. Henry Siddons, the son of the

great Mrs. Siddons, who had married Miss Murray, the

sister of Mr. William Henry Murray, his successor as

manager and lessee, and the granddaughter of Murray of

Broughton, the secretary of the Pretender during the

rebellion of 1745. The Family Legend of Joanna Baillie was

the first new play produced by Mr. Siddons, and Scott took

a great interest in its representation. We learn from

Lockhart’s Life of Scott that he was consulted in all the

minutiae of the costume, attended every rehearsal, and

supplied the prologue. The epilogue was written by Henry

Mackenzie. In a letter to the authoress, dated January

30th, 1810, Scott thus communicates the result:

"MY DEAR MISS BAILLIE,—You have only to imagine all that

you could wish to give success to a play, and your

conceptions will still fall short of the complete and

decided triumph of the Family Legend. The house was

crowded to a most extraordinary degree; many people had

come from your native capital of the west; everything that

pretended to distinction, whether from rank or literature,

was in the boxes, and in the pit such an aggregate mass of

humanity, as I have seldom if ever witnessed in the same

space. It was quite obvious from the beginning, that the

cause was to be very fairly tried before the public, and

that if anything went wrong, no effort, even of your

numerous and zealous friends, could have had much

influence in guiding or restraining the general feeling.

Some good-natured persons had been kind enough to

propagate reports of a strong opposition, which, though I

considered them as totally groundless, did not by any

means lessen the extreme anxiety with which I waited the

rise of the curtain. But in a short time I saw there was

no ground whatever for apprehension, and yet I sat the

whole time shaking for fear a scene-shifter, or a

carpenter, or some of the subaltern actors, should make

some blunder, and interrupt the feeling of deep and

general interest which soon seized on the whole pit, box,

and gallery, as Mr. Bayes has it. The scene on the rock

struck the utmost possible effect into the audience, and

you heard nothing but sobs on all sides. The banquet-scene

was equally impressive, and so was the combat. Of the

greater scenes, that between Lorn and Helen in the castle

of Maclean, that between Helen and her lover, and the

examination of Maclean himself in Argyle’s castle, were

applauded to the very echo. Siddons announced the play

‘for the rest of the week,’ which was received not

only with a thunder of applause, but with cheering and

throwing up of hats and handkerchiefs. Mrs. Siddons

supported her part incomparably, although just recovered

from the indisposition mentioned in my last. Siddons

himself played Lorn very well indeed, and moved and looked

with great spirit. A Mr. Terry, who promises to be a fine

performer, went through the part of the Old Earl with

great taste and effect. For the rest I cannot say much,

excepting that from highest to lowest they were most

accurately perfect in their parts, and did their very

best. Malcolm de Gray was tolerable but stickish—

Maclean came off decently—but the conspirators were sad

hounds. You are, my dear Miss Baillie, too much of a

democrat in your writings; you allow life, soul, and

spirit to these inferior creatures of the drama, and

expect they will be the better of it. Now it was obvious

to me, that the poor monsters, whose mouths are only of

use to spout the vapid blank verse which your modern

playwright puts into the part of the confident and

subaltern villain of his piece, did not know what to make

of the energetic and poetical diction which even these

subordinate departments abound with in the Legend. As the

play greatly exceeded the usual length (lasting till

half-past ten) we intend, when it is repeated to-night, to

omit some of the passages where the weight necessarily

fell on the weakest of our host, although we may hereby

injure the detail of the plot. The scenery was very good,

and the rock, without appearance of pantomime, was so

contrived as to place Mrs. Siddons in a very precarious

situation to all appearance. The dresses were more tawdry

than I should have judged proper, but expensive and showy.

I have got my brother John’s Highland recruiting party to

reinforce the garrison of Inverary, and as they mustered

beneath the porch of the castle, and seemed to fill the

court-yard behind, the combat scene had really the

appearance of reality. Siddons has been most attentive,

anxious, assiduous, and docile, and had drilled his troops

so well that the prompter’s aid was unnecessary, and I do

not believe he gave a single hint the whole night; nor

were there any false or ridiculous accents or gestures

even among the underlings, though God knows they fell

often far short of the true spirit. Mrs. Siddons spoke the

epilogue extremely well: the prologue, which I will send

you in its revised state, was also very well received.

Mrs. Scott sends her kindest compliments of

congratulation; she had a party of thirty friends in one

small box, which she was obliged to watch like a clucking

hen till she had gathered her whole flock, for the crowd

was insufferable. I am going to see the Legend to-night,

when I shall enjoy it quietly, for last night I was so

much interested in its reception that I cannot say I was

at leisure to attend to the feelings arising from the

representation itself. People are dying to read it. If you

think of suffering a single edition to be printed to

gratify their curiosity, I will take care of it. But I do

not advise this, because until printed no other theatres

can have it before you give leave. My kind respects attend

Miss Agnes Baillie, and believe me ever your obliged and

faithful servant, WALTER SCOTT."

The Family Legend had a run of fourteen nights, and

was soon after printed and published by James and John

Ballantyne. (Lockhart’s Life of Scott, pp.

186, 187.) It was afterwards brought out on the London

stage, and the authoress upon one occasion when, in the

year 1815, it was performed at one of the London theatres,

was accompanied to the theatre by Lord Byron and Mr. and

Mrs. Scott, who were then in London, to witness the

representation.

In 1823 she published a ‘Collection of Poetical

Miscellanies,’ which was well received. It contained, with

some pieces of her own, Scott’s dramatic sketch of

Macduff’s Cross, besides several poems by Mrs. Hemans,

some jeux d’esprits by the late Catherine Fanshawe,

and a ballad entitled Polydore, originally published in

the Edinburgh Annual Register for 1810, and written by Mr.

William Howison, author of an ‘Essay on the Sentiments of

Attraction, Adaptation, and Variety.’

In 1836, Miss Baillie published three more voliimes

of plays, all illustrative of her favourite theory. "Even

in advanced age," says a writer in the North American

Review for October 1835, "we see Miss Baillie still

tracing the fiery streams of passion to their

sources,—searching into the hidden things of that dark

mystery, the heart,— and arranging her startling

revelations in the imposing garb of rich and classical

poetry." Among the host of her dramatic writings are the

tragedies of Count Basil, and de Montfort. Sir Walter

Scott has eulogised "Basil’s love and Montfort’s hate," as

something like a revival of the inspired strain of

Shakspeare.

De Montfort was brought out on the London stage by

John Philip Kemble, in 1801, soon after its publication.

The great Mrs. Siddons performed the part of Lady Jane,

and both her acting in the piece as well as that of her

brother, Mr. Kernble, was so powerful that it ought to

have sustained the play had there been any stage vitality

in it. At that period it was acted for eleven nights. It

was then laid aside till 1821, when it was again produced,

to exhibit Kean in the principal character; but that great

actor declared that though a fine poem, it would never be

an acting play. Mr. Campbell, in his life of Mrs. Siddons,

records this remark, and makes the following very just

observations: Miss Baillie "brought to the drama a

wonderful union of many precious requisites for a perfect

tragic writer: deep feeling, a picturesque imagination,

and, except where theory and system misled her, a correct

taste, that made her diction equally remote from the

stiffness of the French, and the flaccid flatness of the

German school; a better stage style than any that we have

heard since the time of Shakspeare, or, at least, since

that of his immediate disciples. But to compose a tragedy

that shall at once delight the lovers of poetry and the

populace is a prize in the lottery of fame, which has

literally been only once drawn during the whole of the

last century, and that was by the author of Douglas. If

Joanna Baillie had known the stage practically, she would

never have attached the importance which she does to the

development of single passions in single tragedies; and

she would have invented more stirring incidents to justify

the passion of her characters, and to give them that air

of fatality which, though peculiarly predominant in the

Greek drama, will also be found to a certain extent, in

all successful tragedies. Instead of this, she contrives

to make all the passions of her main characters proceed

from the wilful natures of the beings themselves. Their

feelings are not precipitated by circumstances, like the

stream down a declivity, that leaps from rock to rock; but

for want of incident, they seem often like water on a

level, without a propelling impulse." (Life of Mrs.

Siddons, vol. ii. p. 254.) The style of her dramas,

however, is regular and vigorous; her plots, though

simple, exhibit both originality and carefulness of

construction; and altogether her plays display a deep and

thorough knowledge of the workings of the human heart. At

right is a portrait of Joanna Baillie from a painting by

Sir W. Newton.

As an authoress, the leading feature of her ge nius

was simple greatness. She had no airs, artifice, or

pretension. Profound subtlety, a deep penetration into

character, and a wonderful fertility of invention, mark

all her dramas. Her touches of natural descrIption, the

wild legendary grandeur which at times floats around her,

the candour, charity, and womanliness of her nature, and

the strong yet delicate imagery in which she enshrines her

thoughts, with her sound morality and the simplicity and

force of her language, impart a pleasing charm to her

writings, and distinguish them from those of all her

contemporaries.

Besides her dramas, Miss Baillie was the authoress

of various poems and songs, on miscellaneous subjects,

which were collected and published in one volume in 1841.

These are, in general, remarkable for their truth and

feeling and harmony of diction, qualities in which she was

surpassed by few modern poets. Among the best of her poems

are, one entitled "The Kitten," which first appeared in an

early volume of the Edinburgh Annual Register, and the

Birthday address to her sister, Miss Agnes Baillie, both

of which have been often quoted. The latter is equal, if

not in some respects superior, to the fine lines of

Cowper, written "On receiving his Mother’s Picture." The

most popular of her songs are, "The Gowan Glitters on the

Sward ;" " Welcome Bat and Owlet Gray ;" "Good Night, Good

Night ;" "It fell on a Morning ;" which originally

appeared in the collection of Scotch songs called ‘The

Harp of Caledonia,’ edited by John Struthers, and

published in Glasgow in 1821; ; "Woo'd and Married and a’

;" and" Hooly and Fairly." The two latter were written for

Mr. George Thomson’s celebrated collection of Scotch

melodies, as was also " When white was my o’erlay as foam

o’ the linn," a new version of "Todlin Hame." Her Scotch

songs, distinguished by their simplicity, their quiet

pawky humour, and pastoral tenderness, are known by heart

by all Scotsmen.

Miss Baillie passed the greater portion of her life

in retirement, and in her latter years in strict

seclusion, at her villa at Hampstead, where she died on

the 23d February 1851, in her eighty-ninth year, retaining

all her faculties to the last.

Her sister, who was also a poetess, and to whom she

was much attached, always resided with her. The following

lines are from the beginning of an ‘Address to her Sister

Agnes, on her Birthday:’

"Dear Agnes, gleamed with joy and dashed with tears,

O’er us have glided almost sixty years,

Since we on Bothwell’s bonny braes were

By those whose eyes long closed in death have been,

Two tiny imps, who scarcely stooped to gather

The slender harebell on the purple heather;

No taller than the foxglove’s spiky stem,

That dew of morning studs with silver gem.

Then every butterfly that crossed our view

With joyful shout was greeted as it flew;

And moth, and ladybird, and beetle bright,

In sheeny gold, were each a wondrous sight.

Then as we paddled barefoot, side by side,

Among the sunny shallows of the Clyde,