|

ALLAN,

a name meaning, in the British, Alan, swift like a greyhound; in

the Saxon, Alwin, winning all; and in the Celtic, Aluinn,

when applied to mental qualities or conduct, illustrious. The primary

meaning of the word, however, is sparkling or beautiful, and it is on that

account the name of several rivers, particularly one in Perthshire, which

waters the fertile district of Strathallan. It is the opinion of Chalmers

that the Alauna of Ptolemy and of Richard of Westminster, (in his

Itinera Romana, a work referable to the second century,) was situated

on the Allan, about a mile above its confluence with the Forth, so that

the name has an ancient as well as a classical origin. The popular song of

‘On the banks of Allan Water,’ is supposed to refer to a smaller stream of

the same name, a tributary of the Teviot. Allan is also not unfrequently a

Christian name in Scotland, as Allan Ramsay.

ALLAN, DAVID,

an eminent historical painter, the son of David Allan, shoremaster at

Alloa, was born there on 13th February 1744. His mother, Janet Gullan, a

native of Dunfermline, died a few days after his birth, and it is related

of him that, when a baby, his mouth was so small that no nurse in his

native place could give him suck, and a countrywoman being found, after

some inquiry, a few miles from the town, whose breast he could take, he

was, one very cold day, after being wrapped up in a basket, amidst cotton,

to keep him warm, sent off to her under the charge of a man on horseback.

On the road the horse stumbled, the man fell off, and the little Allan

being thrown out of the basket, among the snow which then covered the

ground, received a severe cut on his head. While yet a mere child of

little more than eighteen months old, he experienced another narrow escape

from a premature death. The servant girl who had the care of him, while

out with him in her arms one day in the autumn of 1745, thoughtlessly ran

in front of some loaded cannons, at the very moment that they were fired

by way of experiment, but she and the child were providentially not

touched.

Like that of

many other great painters, his genius for designing was discovered by

accident. Being when a boy kept at home from school, on account of a burnt

foot, his father seeing him one day doing nothing, reproved him for his

idleness, and giving him a bit of chalk, told him to draw something with

it on the floor. He accordingly attempted to delineate figures of houses,

animals, &c., and was so well pleased with his own success, and so fond of

the amusement, that the chalk was seldom afterwards out of his hand. His

sense of the ludicrous was great, and he could not always resist the

propensity to satire. Having when about ten years of age drawn a

caricature on his slate of his schoolmaster, a conceited old dominie,

who used to strut about the school attired in a tartan nightcap and

long tartan gown, and circulated it among the boys, it fell into the hands

of the object of it, who straightway complained to Allan’s father, and he

was in consequence withdrawn from his school. On being questioned by his

father as to how he had the impudence to insult his master in such a way,

he answered, "I only made it like him, and it was all for fun." In one

account of his life it is stated that the first rude efforts of his genius

were formed merely by a knife, and displayed a degree of taste and skill

far above his years; and these having attracted the notice of Mr. Stewart,

then collector of the customs at Alloa, that gentleman, when at Glasgow,

mentioned the merits of young Allan to Mr. Foulis, the celebrated printer,

and he was sent, on the 25th of February 1755, when eleven years of age,

to the Messrs. Foulis’ academy of painting and engraving at Glasgow, where

he remained seven years. In the year 1764 some of his performances

attracted the notice of Lord Cathcart of Shaw Park, near Alloa. At the

expense of his lordship, Mr. Abercromby of Tullibody, and other persons of

fortune in Clackmannanshire, to whom his talents had recommended him,

among whom were Lady Frances Erskine of Mar, and Lady Charlotte Erskine,

he afterwards proceeded to Italy, and studied for sixteen years at Rome.

In 1775, he received the gold medal given by the academy of St. Luke, in

that city, for the best specimen of historical composition; the subject

being ‘The Origin of Painting, or the Corinthian Maid drawing the Shadow

of her Lover;’ an admirable engraving of which was executed at Rome by

Dom. Cunego in 1776, and of which copies were published by him in February

1777, after his return to London. Mr. Allan presented the medal received

by him for this painting to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, on the

7th January 1783, and an account of it was published in their

transactions, vol. ii. pp. 75, 76. The only other Scotsman who had ever

received the gold medal of St. Luke’s academy was Mr. Gavin Hamilton.

After a residence of two years in London, he returned to Edinburgh, in

1779, and, on the death of Alexander Runciman in 1786, was appointed

director and master of the academy established by the board of trustees

for manufactures and improvements in Scotland. In 1788 he published an

edition of the Gentle Shepherd, with characteristic etchings. In

‘Observations on the Plot and Scenery of the Gentle Shepherd,’ from

Abernethy and Walker’s edition (Edinburgh: 1808), reprinted in edition of

A. Fullarton & Co., 1848 (vol. ii. p. 25.), the following passage occurs:

"In 1786, an unexpected visit was paid at New Hall house, (the romantic

seat of Mr. John Forbes, advocate, situated in the parish of Penicuick,

Edinburghshire, the scenery round which is supposed to have been that of

the Gentle Shepherd,) by Mr. David Allan, painter in Edinburgh,

accompanied by a friend, both of whom were unknown to the family. His

object was to collect scenes and figures, where Ramsay had copied his, for

a new edition of the pastoral. Mr. Allan was an intelligent Scottish

antiquarian, and well acquainted with everything connected with the poetry

and literature of his country. His excellent quarto edition was published

in 1788, with aquatinta plates, in the true spirit and humour of Ramsay.

Four of the scenes at New Hall are made use of with some figures collected

there; and in his dedication to Hamilton of Murdiston in Lanarkshire, the

celebrated historical painter, he writes, ‘I have studied the same

characters’ (as those of Ramsay), ‘from the same spot, and I find that he

has drawn faithfully, and with taste, from nature. This likewise has been

my model of imitation, and while I attempted, in these sketches, to

express the ideas of the poet, I have endeavoured to preserve the costume

as nearly as possible, by an exact delineation of such scenes and persons

as he actually had in his eye." Mr. Allan published also, some time after,

a collection of the most humorous old Scottish songs, with similar

drawings ; these publications, with his illustrations of the Cottar’s

Saturday Night, the Stool of Repentance, the Scottish Wedding, the

Highland Dance, and other sketches of rustic character, all etched by

himself in aquatinta, procured for him the title of the Scottish Hogarth.

One of his subjects, representing a poor man receiving charity from the

hand of a young woman, is here copied.

As

an instance of simple character and feeling without caricature, it gives a

tolerably good idea of his natural manner, and illustrates the particular

locality of Edinburgh of that epoch, where its scene is laid. It, as well

as the view of the General Assembly, which appears in another part of this

volume, was also etched by himself. He likewise etched and published

various subjects drawn when in Italy, exhibiting the peculiarities of the

people, and especially the devotional extravagances of the church of Rome

of that time, which appear to have excIted his sense of the ludicrous.

Besides these he published four engravings, done in aquatinta by Paul

Sandby, from drawings made by himself when at Rome, where, in a vein of

quiet drollery, he holds up to ridicule the festivities of that city in

connection with the sports of the carnival. Several of the figures were

portraits of persons well known to the English who visited Rome during his

stay there, and their truthfulness gave much satisfaction at the time.

His personal appearance was not in his favour. "His figure," says the

author of his life in Brown’s Scenery edition of the Gentle Shepherd,

1808, "was a bad resemblance of his humorous precursor of the English

metropolis. He was under the middle size; of a slender, feeble make; with

a long, sharp, lean, white, coarse face, much pitted by the small pox, and

fair hair. His large prominent eyes, of a light colour, looked weak, near-

sighted, and not very animated. His nose was long and high, his mouth

wide, and both ill-shaped. His whole exterior to strangers appeared

unengaging, trifling and mean. His deportment was timid and obsequious.

The prejudices naturally excited by these external disadvantages at

introduction, were soon, however, dispelled on acquaintance; and, as he

became easy and pleased, gradually yielded to agreeable sensations; till

they insensibly vanished, and were not only overlooked, but, from the

effect of contrast, even heightened the attractions by which they were so

unexpectedly followed. When in company he esteemed, and which suited his

taste, as restraint wore off, his eye imperceptibly became active., bright

and penetrating; his manner and address quick, lively, and interesting —

always kind, polite, and respectful; his conversation open and gay,

humorous without satire, and playfully replete with benevolence,

observation, and anecdote." He resided in Dickson’s close, High street,

Edinburgh, where he received private pupils in his art. One of the most

celebrated of his pupils was the late Mr. H. W. Williams, commonly called

Grecian Williams. "The satiric humour and drollery," says Mr. Wilson, in

his Memorials of Edinburgh. (vol. ii. rage 40), "of his well-known ‘rebuke

scene’ in a country church, and the lively expression and spirit of the

‘General Assembly,’ and others of his own etchings, amply justify the

character he enjoyed among his contemporaries as a truthful and humorous

delineator of nature." "As a painter," says the author of his life already

quoted; "at least in his own country, he neither excelled in drawing,

composition, colouring, nor effect. Like Hogarth, too, beauty, grace, and

grandeur, either of individual outline and form, or of style, constitute

no part of his merit. He was no Corregio, Raphael, or Michael Angelo. He

painted portraits, as well as Hogarth, below the size of life; but they

are recommended by nothing save a strong homely resemblance. As an artist

and a man of genius, his characteristic talent lay in expression,

in the imitation of nature with truth and humour, especially in the

representation of ludicrous scenes in low life. His vigilant eye was ever

on the watch for every eccentric figure, every motley group, or ridiculous

incident, out of which his pencil or his needle could draw innocent

entertainment and mirth." He died at Edinburgh on the 6th of August 1796,

in the 53d year of his age, and was interred in the High Calton

burying-ground. He had married in 1788 Shirley Welsh, the youngest

daughter of Thomas Welsh, a carver and gilder in Edinburgh. He had five

children, three of whom died in infancy. His surviving son, David, went

out as a cadet to India in 1806. He also left a daughter named

Barbara.—Brown’s Scenery edition of the Gentle Shepherd, appendix.

ALLAN,

ROBERT,

a minor poet, some of whose lyrics and songs have long been popular in

Scotland, was born at Kilbarchan, in Renfrewshire, 4th November, 1774. He

was a handloom weaver, and all his life in humble circumstances. To

relieve the tedium of his occupation he occasionally had recourse to

poetry. In 1836, a volume of his poems was published by subscription, but

made no great impression. The principal poem in the volume, entitled ‘An

Address to the Robin,’ is written in the Scottish dialect. His most

popular pieces are ‘The bonny built wherry;’ ‘The Covenanter’s Lament;’

‘Woman’s wark will ne’er be dune;’ ‘Hand awa’ frae me, Donald;’ and the

ballad ‘O speed, Lord Nithsdale.’ He had a numerous family, all of whom

were married except his youngest son, a portrait painter of great promise,

who emigrated to the United States. Desirous of joining his son, Allan

sailed for New York, where he arrived 1st June 1841, but died there on the

7th, six days after his arrival, from the effects of a cold caught on the

banks of Newfoundland. He is represented as having been a most

single-hearted and unaffected being, and much of the simplicity of his

character is reflected in his poems.

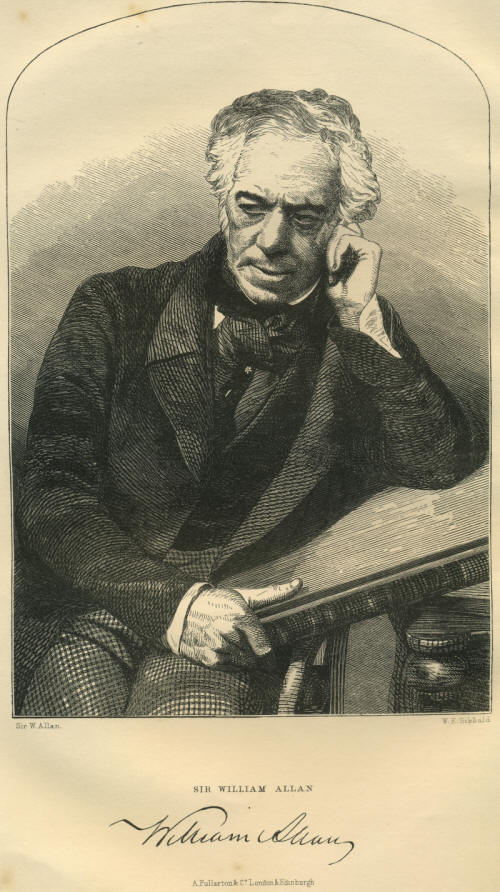

ALLAN,

SIR WILLIAM,

an eminent historical painter, was born at Edinburgh,

in 1782,

of humble parentage, his father being one of the doorkeepers of the Court

of Exchequer. He was educated partly at the High School of his native

city, under William Nicol, the friend of Burns, and served his

apprenticeship to a coach-painter, George Sanders the celebrated

miniature-painter being in the same employment. All his spare hours were

devoted to drawing. He studied for several years at the Trustees’ Academy,

having Wilkie as a fellow-student. These two great painters began drawing

from the same example, and thus continued for months, using the same copy,

and sitting on the same form. The friendship thus commenced in their youth

increased with their years, and ceased but with the life of Wilkie, who

died nine years before him. One of his first pieces engraved was ‘Flora

parting with Ascanius,’ in Home’s ‘Adventures of the young Ascanius,’

1804. After the close of his studies in Edinburgh, Allan removed to

London, and was admitted to the school of the Royal Academy, where he

remained some time. Not ultimately finding professional employment in

London, he determined upon proceeding to Russia, to try whether

encouragement could not be obtained in that country, and that he might

study the rude and picturesque aspects there presented, and find suitable

and striking materials for his pencil. Hastily communicating his intention

to his friends in Scotland, with one or two letters of introduction to

some of his countrymen at St. Petersburg, he embarked in 1805 in a vessel

bound for Riga. Owing to adverse winds the ship, almost a wreck, was

driven into Memel in Prussia, where, though ignorant of the German

language, he took up his abode at an inn, and at once commenced

portrait-painting. He began with the portrait of the Danish consul, to

whom he had been introduced by the captain of the vessel. Having, in this

way, recruited his nearly empty purse, he proceeded overland to St.

Petersburg, encountering on the road various romantic incidents, and

passing through a great portion of the Russian army on their way to the

battle of Austerlitz. On his arrival at the Russian capital, he was

introduced to many valuable friends, through the kindness of Sir Alexander

Crichton, then physician to the Imperial family; and was soon enabled to

pursue his art diligently, and successfully. Having attained a knowledge

of the Russian language, he travelled into the interior, and remained for

several years in the Ukraine, making excursions at various times to

Turkey, Tartary, the shores of the Black Sea, the Sea of Azoph, and the

banks of the Kuban, amongst Cossacks, Circassians, Turks, and Tartars;

visiting their huts and tents, studying their history, character, and

costume, and forming a collection of their arms and armour, for his future

labours in art, as he had resolved to devote his great powers to

historical painting.

In 1812,

Mr. Allan began to think of returning to Scotland, but was prevented by

the French invasion of Russia of that year. The whole country was thrown

into confusion and alarm by the Emperor Napoleon’s advance to Moscow, and

thus was Allan forced to remain, when he witnessed not a few heart -

rending miseries incident to that eventful period. In 1814, however, he

was enabled to set out on his return home, and, after a lapse of ten

years, he once more trod the streets of Edinburgh. His improvement had

been so rapid and so remarkable, that the most eminent of his countrymen

in literature and art visited, and were in daily intercourse with, the

young and enterprising artist, and he numbered among his friends Scott,

Wilson, Lockhart, and other distinguished literati of the day in

Edinburgh, which city he resolved to make his future residence. His first

efforts, after his return, were directed to embodying on the canvass, some

of those romantic and striking scenes which had been suggested by his

travels and adventures in the strange countries he had visited. His

‘Circassian Captives,’ a work full of novel and original matter,

character, and expression, and remarkable for the completeness of its

design, and the masterly arrangement of its parts, was exhibited at

Somerset House, London, in 1815, and immediately made his name generally

known. To this great picture succeeded ‘Tartar Banditti;’ ‘Haslan Gheray

crossing the Kuban;’ ‘A Jewish Wedding in Poland;’ and ‘Prisoners Conveyed

to Siberia by Cossacks,’ which, with many others, he brought together, and

exhibited in Edinburgh, along with the armour and costumes he had

collected in his travels. The exhibition proved highly attractive, and the

artist rose higher in the estimation of his countrymen. His picture of

‘The Circassians’ was purchased by Sir Walter Scott, John Wilson, the

poet, his brother, James, the naturalist, Lockhart, and a number of the

artist’s other friends, and it was resolved to raffle it in Edinburgh. In

a letter to the Duke of Buccleuch, dated 15th April, 1819, Sir Walter

Scott, who took a great interest in Allan, thus gives an account of the

circumstance, and of the artist himself ;—" A hundred persons subscribed

ten guineas apiece to raffle for his fine picture of the Circassian chief

selling slaves to the Turkish pacha—a beautiful and highly poetical

picture. There was another small picture added by way of second prize,

and, what is curious enough, the only two peers on the list, Lord Wemyss

and Lord Fife, both got prizes. Allan has made a sketch, which I shall

take to town with me when I can go, in hopes Lord Stafford, or some other

picture-buyer, may fancy it, and order a picture. The subject is the

murder of Archbishop Sharpe on Magus Moor, prodigiously well treated. The

savage ferocity of the assassins, crowding on one another to strike at the

old prelate on his knees, contrasted with the old man’s figure, and that

of his daughter endeavouring to interpose for his protection, and withheld

by a ruffian of milder mood than his fellows—the dogged, fanatical

severity of Rathillet’s countenance, who remained on horseback,

witnessing, with stern fanaticism, the murder he did not choose to be

active in, lest it should be said that he struck out of private

revenge—are all amazingly well combined." The picture which Allan executed

from the sketch here described by Sir Walter Scott, was worthy of his

genius. It was afterwards engraved, and is well known. The painting itself

is in the possession of Mr. Lockhart, of Milton-Lockhart. Sir Walter

added:—" Constable (the eminent publisher) has offered Allan three hundred

pounds to make sketches for an edition of the ‘Tales of my Landlord,’ and

other novels of that cycle, and says he will give him the same sum next

year, so, from being pinched enough, this very deserving artist suddenly

finds himself at his ease. He was long at Odessa with the Duke of

Richelieu, and is a very entertaining person."

During the visit of the Grand Duke Nicholas, afterwards Czar of Russia, to

Edinburgh, about this time, he purchased several of Allan’s pictures; one,

the ‘Siberian Exiles,’ and another, ‘Haslan Cheray,’ both already

mentioned. Allan’s works were now readily bought. His most affecting

picture, ‘The Press-Gang,’ was purchased by Mr. Horrocks of Tillyheeran;

his ‘Knox admonishing Mary, Queen of Scots,’ a work full of character, by

Mr. Trotter of Ballendean; and his ‘Death of the Regent Moray,’ by the

then duke of Bedford. A serious malady in his eyes, which was a source of

suffering for several years, caused a cessation from all professional

labours. A change of climate being advised by his physician, he went to

Italy, and after spending a winter at Rome, he proceeded to Naples, and

thence made a journey to Constantinople. He afterwards, with restored

health, visited Morocco, Greece, Spain, and the wild range of country from

Gibraltar to Persia, and from Persia to the Baltic, for the purpose of

studying the scenery and manners of the various nations through which he

passed. These he faithfully embodied on his canvass, and among his

greatest pictures in this style may be noticed, ‘The Discovery of the Cup

in the Sack of Benjamin;’ ‘The Polish Captives;’ ‘The Slave Market at

Constantinople,’ which was purchased by Alexander Hill, Esq.,

print-publisher; ‘Tartar Banditti Dividing their Spoil;’ ‘The Moorish

Love-Letter;’ ‘Byron in the Fisherman’s Hut, after Swimming the

Hellespont,’ which was bought by his friend Robert Nasmyth, Esq., who was

also the purchaser of his whole-length cabinet portraits of ‘Scott and

Burns.’ The eastern pieces named were executed after his return to

Edinburgh, with numerous others, descriptive of oriental scenery, persons,

and manners. The history of his own land also furnished him with subjects

for his powerful and graphic pencil. Besides ‘The Murder of Archbishop

Sharpe,’ and ‘The Death of the Regent Moray,’ he devoted his genius to

many other scenes illustrative of our Scottish annals, so fruitful in

remarkable and striking events. His painting of Mary and Rizzio is one of

the best of these historic pictures.

In

his famous picture of ‘The Ettrick Shepherd’s House-heating,’ executed in

1819, he introduced a portrait of his friend Sir Walter Scott, who had

always a great regard for him. His figure of ‘The Author of Waverley in

his Study,’ done shortly before Sir Walter’s death, is considered one of

his most successful efforts in this department of art. He also finished an

admirable painting of Sir Walter’s eldest son, when cornet of dragoons,

holding his horse, which hangs over the mantelpiece of the great library

at Abbotsford. He was there during the last melancholy scenes of Scott’s

life. Mr. Lockhart says, "Perceiving, towards the close of August 1832,

that, the end was near, and thinking it very likely that Abbotsford might

soon undergo many changes, and myself, at all events, never see it again,

I felt a desire to have some image preserved of the interior apartments as

occupied by their founder, and invited from Edinburgh, for that purpose,

Sir Walter’s dear friend, William Allan, whose presence, I well knew,

would, even under the circumstances of that time, be nowise troublesome to

any of the family, but the contrary in all respects. Mr. Allan willingly

complied, and executed a series of beautiful drawings. He also shared our

watchings, and witnessed all but the last moments."

In

1834 he visited Spain, with the object of collecting fresh materials for

the subjects of his art. He sailed for Cadiz and Gibraltar, proceeded into

West Barbary, and crossing again into Spain, travelled over the greater

part of Andalusia, intending to go on to Madrid, but was recalled to

Scotland, by news from home.

In

1835 Mr. Allan was elected a member of the Royal Academy, and in 1838 he

was chosen president of the Royal Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture,

and Architecture, on the death and in the room of Mr. Watson, the original

president. In 1841, on the death of Sir David Wilkie, he was appointed her

Majesty’s limner for Scotland, and in the following year he was knighted.

He was an honorary member of the Academies of New York and Philadelphia.

Having long intended to paint a picture of the Battle of Waterloo, he

several times visited France and Belgium to make sketches of the memorable

field, and to collect the requisite materials for his purpose. The view he

chose was from the French side, Napoleon and his staff being the

foreground figures. This picture was, in 1843, exhibited at the Royal

Academy, London, and purchased by the Duke of Wellington, who expressed

his high satisfaction at the truthfulness of the arrangement and detail in

his work. He was subsequently induced, by the success of the first, to

paint another great picture of Waterloo, from the British side, with the

view of entering the lists of the West minster Hall competition of 1846.

This piece also gained the approbation of the Duke of Wellington, and was

much praised by the public, but though voted for by W. Etty, R.A., one of

the best judges in the committee, as worthy of public reward, it was not

judged deserving of a prize.

In

1844 Allan revisited Russia, and had an opportunity of again seeing his

early patron, the Emperor Nicholas. While there he painted a picture of

‘Peter the Great teaching his subjects the art of shipbuilding,’ which is

now in the winter palace of St. Petersburgh.

After his return to his native city, he continued his professional

labours, with the enthusiasm that ever marked his character. His last

energies were expended on a national piece, and one commemorative of the

most remarkable event in the history of Scotland’s independence, namely,

‘The Battle of Bannockburn,’ on the same extensive scale as his latter

picture of Waterloo. On this picture he worked with as much diligence as

his weakened condition would admit, for already his last illness was upon

him. So eager was he to complete the work in time for the ensuing

exhibition of the Royal Academy, that, it is stated, he had his bed

carried into his painting room that he might sleep near his work. When the

pencil at length fell from his hand he was too far gone in illness to be

removed, and he died in his painting room, in front of his latest picture.

He was never married, his niece having kept house for him.

Sir William died at his residence, 72 Great King Street, Edinburgh, on the

23d February, 1850, in the 69th year of his age. He had for

many

years been afflicted with chronic disease of the windwipe, and had

latterly become much enfeebled. His genius as an artist was of the highest

order, and he possessed singularly unassuming manners and an amiable

disposition. As an instance of his kindly feeling, it may be stated that

on a few of the scholars of Mr. John Robertson, the first teacher in

Gillespie’s hospital, Edinburgh, who had been educated in that institution

under his charge, wishing to have the portrait taken of their old master,

two of them waited on Sir William Allan to ascertain if his engagements

would permit him to do it, and on what terms, when, appreciating their

motives, he at once generously agreed to paint Mr. Robertson’s portrait

without remuneration, and it is now in the hall of the hospital. Sir

William was much esteemed, not only by his brother artists, but by an

extensive circle of friends. A picture of his commemorative of the Ettrick

Shepherd’s birthday, at Hogg’s house at Altrive, after a day’s sport in

trouting and rambling on the mountains, contains nineteen portraits of the

Shepherd’s intimate friends and his own, in rural costumes, among whom,

besides Hogg and himself, are Sir Walter Scott; his son-in-law John Gibson

Lockhart; the two Ballantynes, James and John; Professor Wilson and his

brother James; Captain Thomas Hamilton, author of ‘Cyril Thornton;’

Alexander Nasmyth, the celebrated landscape painter; David Brydges;

Constable the publisher; James Russell, the comedian; and James Bruce,

piper to Sir Walter Scott; a list of names calculated to make the painting

interesting, although not among the most finished of the artist’s

performances. It is now the property of Mrs. Gott of Armsly House.

Sir William Allan was for a long period the only resident historical

painter of his country, and for seventeen years master of the Trustees’

academy, at Edinburgh, where he and Wilkie first began their career. His

excellence as a painter consisted in his dramatic power of portraying a

story, and his general skill in composition, rather than in character or

in colour. He will be remembered in the history of Scottish art by the

impulse which he gave to historical composition; while his name will

always be endeared to the admirers of Sir Walter Scott by the strong

partiality which the latter evinced on all occasions for his friend

"Willie Allan." With the office of limner to the queen for Scotland, which

Allan received in 1842, the honour of knighthood is always conveyed to its

holder. A small salary also accompanies it. The office was revived by

George the Fourth, and given to Sir Henry Raeburn, and at Raeburn’s death

it was conferred on Sir David Wilkie, who was succeeded by Sir William

Allan. At the death of the latter, Sir James Watson Gordon, R.A.,

president and trustee of the Royal Scottish Academy, was appointed in his

place. A portrait of Sir William Allan is given separately. Besides Wilkie,

John Burnet the engraver, Alexander Fraser the painter, and others eminent

in art, were his fellow students at the Trustees’ Academy, Edinburgh. When

he first went to London, Opie, the Cornish painter, was then at the height

of his reputation, and in the first picture which Allan sent to the Royal

Academy, he imitated Opie’s style, so far as colour went, with something

like servility. This picture, called ‘A Gipsy and Ass,’ was exhibited in

1805. His ‘Russian Peasants Keeping Holiday,’ was exhibited in 1809.

Besides the pictures above mentioned, he also painted the following :—‘

Circassian Prince on Horseback selling two boys of his own nation to a

Cossack chief of the Black Sea ;‘ ‘ Circassian Chief selling to a Turkish

Pasha Captives of a neighbouring tribe taken in war;’ ‘The parting between

Prince Charles Stuart and Flora Macdonald at Portree;’ and ‘Jeanie Deans’

first interview with her father after her return from London.’

The

name Allan from the Dictionary of National Biography

David Allan

Peter Allan |