|

ALEXANDER I.,

king of Scotland, surnamed the Fierce, from his vigour and impetuous

character, has hitherto been represented as the fifth son of Malcohn III.,

surnamed Canmore, or great head, by Margaret, daughter of Edward, nephew

of Edward the Confessor, king of England, but it is now admitted that

Ethelred, who had been believed to be the third, was the youngest son of

that marriage, and consequently Alexander was not the fifth but the fourth

son of Malcolm and Margaret. It is also placed beyond a doubt that by a

previous marriage with Ingibiorge, the widow of Thorfin, a powerful

Norwegian earl,—who for thirty years, during the reigns of Alexander’s

father Malcolm and his predecessor Macbeth, ruled over all Scotland north

of the Grampians, and part of the present county of Forfar,—Malcolm had

two sons, Duncan, afterwards king of Scotland, and Malcolm, both of whom

were alive at the time of his death, so that Alexander was in reality the

sixth of the sons of Malcolm Canmore. (See life of Duncan, king of

Scotland, post.) There is no earlier instance in Scottish history

of the name of Alexander having been borne by king or noble, although it

afterwards became one of the most common and familiar Christian names in

Scotland. Lord Hailes has supposed that it was bestowed in honour of Pope

Alexander II. If so, it was given to him after the death of that pontiff,

which occurred in the year 1073, as no calculation from family or other

events can place the birth of Alexander, of which the precise date is

unknown, earlier than about the year 1078.

Alexander was

educated with great care, not only in letters but in religious principles,

and the solemn injunctions of his excellent mother, on her death-bed, to

Turgot, prior of Durham, her confessor and biographer, which have

descended to us in his interesting memoir of that good queen, prove how

great was her solicitude in the latter respect in regard to all her

children. Alexander partook of those vicissitudes of the family, after the

death of his father, which are detailed in the lives of his uncle Donald

Bane and of his brothers Duncan and Edgar, and which serve to exhibit, in

a strong light, the peculiarities of the law of succession to the throne

among the Celtic or Pictish races of that age, and they no doubt

contributed to form and give a direction to his character and future

government, when he became king.

On the death of

his brother Edgar, 8th January 1107, Alexander succeeded to the throne,

but not to the enjoyment of the same extent of possessions as his

predecessor. For the conquest of the western portion of the ancient

principality of Cumbria—a region extending between the Roman walls

of Agricola and Antoninus—having sometime previous been effected, by David

his younger brother, with an army of Norman chivalry from England, the

government of the province was also bestowed upon him, and Edgar, on his

death-bed, bequeathed him all those extensive lands in those regions held

by him and Malcolm his father which formed the subject of that homage

rendered to the Norman conqueror and his son William Rufus so frequently

referred to in English history. (Lord Hailes’ Quotations from

English contemporary writers, compared with the narrative of the

inquisition into the lands of the see of Glasgow, and existing charters of

that epoch.) All Scottish historians, from the fourteenth until within the

present century, have concurred in stating that the province of Cumbria

corresponded exactly in territory with the present English county of

Cumberland, but charters, and Saxon as well as earlier Scottish writers,

when correctly understood, leave it beyond doubt that the portion of

country so called comprehended the district extending from the Clyde to

the Solway, and included all the present Scottish counties of Ayr,

Galloway, Wigton, Kirkcudbright, and Dumfries, with perhaps part of

Cumberland; the district of Lothian, comprising the three counties which

still bear that name; and the shires of Renfrew and Lanark, with part of

Lennox now Dumbartonshire. Such distributions of the royal possessions

amongst the members of their family were not uncommon with the monarchs of

that age.

Whatever were

the motives that led to this disjunction from the Scottish crown, it

proved a fortunate arrangement for the nation. By the subsequent death of

Alexander without issue, and the consequent succession of David to the

northern throne, the danger of contention between rival farniiies for

these possessions, and of their permanent separation from the ancient

kingdom, was averted, and a united kingdom was afterwards formed, able,

with more or less success, to withstand the powerful neighbouring southern

state; which, if it had continued disjoined, would most probably have

fallen to it by piecemeal a comparatively easy prey. While, on the one

hand, the happy genius of David for government, and for attracting towards

himself the love and affection of all classes of people committed to his

care, enabled him to introduce amongst them order and civilization, and to

combine Saxon law with Norman refinement, as well as the still higher

blessing of religious instruction, and while his amiable qualities and the

accident of his birth endeared through him the family of Malcolm to the

Saxon race, so that nearly four hundred years afterwards an English writer

resident in Scotland thus commemorates one of them:

"Our soverane of

Scotland

Quhilk sall be lord and ledar

Oer broad Brettane all quhair

As saint Mergarettes air;"

(Duke of the Howlat, st. xxix, printed for the Bannatyne

Club.)

the sterner rule of

Alexander was made available to keep under the dissatisfied feelings of

the warlike tribes of the north, not less averse to that deviation from

the ancient rule of succession by which the descendants of Margaret were

placed on the throne, than jealous of the innovations of Saxon law and

Saxon settlements. It was not, however, to be expected that to this

disposition of lands Alexander would at once quietly accede. On the

contrary, he at first disputed its validity, and would willingly have

annulled it, had he not found that the powerful barons of the province in

question, and of the northern English counties, as Gospatrick, Baliol,

Bruce, Lindesay, Areskine, and others, whose descendants afterwards

occupied the first rank among the Scottish nobility, and by the aid of

whose arms his brother Edgar had been placed and sustained on the throne,

were entirely favourable to this arrangement. He therefore prudently

desisted from the attempt, and confined himself during the remainder of

his reign to the northern portion of the kingdom. (Speech of Walter

l’Espec at the battle of the Standard, in AEldred.) It has been

inferred by modern writers who have recognised the foregoing as the

territorial limits of Cumbria, that David held this government as a fief

in subordination to Alexander, but this does not appear to have been the

case. David seems to have regulated the affairs of his government as an

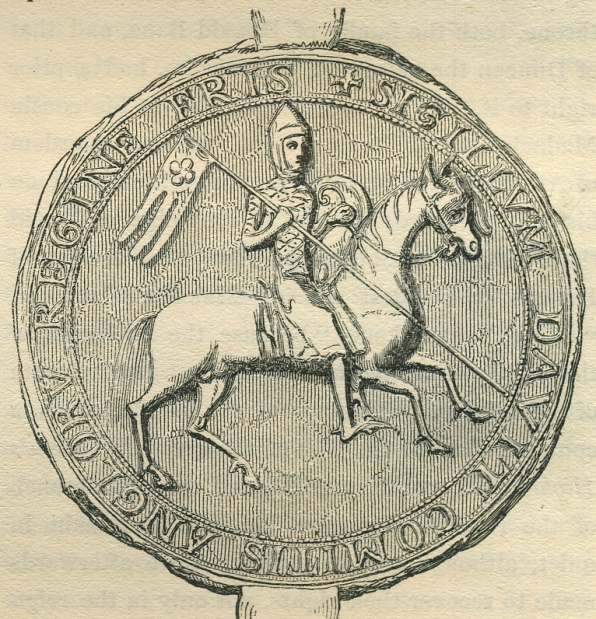

independent prince. The motto of his seal during his brother’s lifetime

bears that he styled himself ‘David, Comites Anglorum Regene Fratris,

(contracted into Fris); that is, David the count, brother of the Queen of

the English. At right is a representation of David’s seal.

Several

of his public instruments, too, after he ascended the throne, when

relating to matters affecting the southern districts, are addressed to the

"Francis et Anglicis," Normans and English, (Anderson’s Diplomata et

Numismata, No. 17, 1 and 2); and at a later period, or when referring

to matters of more importance, to the "Francis et Angilcis, et Scottis et

Galwensibus," that is, the Normans, English, Scotch, and Galwegians, which

latter style was uniformly adopted by his successor and grandson Malcolm

IV., (Idem, plates 19, 23, 25,) whilst the public instruments of

Alexander are simply addressed to the Scots and English, "Scottis et

Anglis" (Idem, page 9), showing that he only ruled over the

northern portion of the kingdom in which these nations lived in the

proportion of the order in which they are placed.

It

was fortunate both for Alexander and David, and for the tranquillity of

the government of the former, that during the entire period of his reign

an unbroken peace was maintained with England. The marriage of their

sister Matildis in 1100, during the life of their brother Edgar, with

Henry king of England the brother of William Rufus, greatly facilitated

this harmony, and it was further cemented by the union of Alexander with

Sybilla, natural daughter of that monarch. Such an alliance, says Lord

Hailes, was not held dishonourable in those days.

The people of the north were not reconciled to the sovereignty of the sons

of Malcolm. According to their notions of the law of succession to the

throne, both the family of Donald Bane, and that of Duncan the eldest son

of Malcolm, had a prior right to it. Edgar had bestowed upon his cousin

Madach, son of Donald Bane, the maormordom of Athol, erected by him into

an earldom, and on his death, towards the end of the reign of David the

First, it was obtained by Malcolm, the son of Duncan, the eldest son of

Malcolm Canmore, "either," says Skene, "because the exclusion of that

family from the throne could not deprive them of the original patrimony of

the family, or as a compensation for the loss of the crown," (Skene’s

Highlanders, vol. ii. p. 139,) and thus this branch of the rival

family were induced to remain in quiet, although various attempts were

afterwards made to recover their rights, not only in the reign of Malcolm

IV., but for nearly a hundred years after they were excluded from it.

The descendants of Donald Bane appear to have enjoyed another portion of

the hereditary possessions of the family in the person of Ladman his son,

and along with them some title which does not appear. Even the descendants

of Macbeth seem, in the person of Angus the son of the daughter of Lulach,

Macbeth’s nephew, to have got the possessions and ancient maormordom of

Moray erected into an earldom of that name. (Skene’s High-landers,

vol. ii. p. 162.) According to the Annals of Ulster about 1116, a

descendant of Malpedir, maormor of Moern or Garmoran, a district in

northern Inverness-shire, one of the supporters of Donald Bane, and who

had murdered Duncan, eldest son of Malcolm, in 1095, was in possession of

his father’s title and lands, and at the instigation of Ladman, in order

probably to revenge his death, he combined with Angus earl of Moray,

already referred to as of the family of Macbeth, to make an attempt to

seize upon the person of Alexander. At his baptism Alexander had a

donation made to him of the lands of Blairgowrie and Liff by his

godfather, Donald Bane, then probably maormor of Athol, and in the first

year of his reign he began to build a palace or residence in the vicinity;

but while engaged on this work the Highlanders of Moern (not Mearns, as

commonly supposed) and Moray penetrated stealthily from their northern

abodes to Invergowrie, where Alexander was, and surprised him by night.

Alexander escaped to the shore, and crossing over the Tay to Fife,

collected vassals, and followed them with surprising activity, through the

‘Monthe’ or Grampians, across the Spey and over the "Stockfurd into Ros."

Of this passage Wintoun says,

"He

tuk and slew thame or he past

Out of that land, that fewe he left

To take on hand swylk purpose eft."

And

again he adds,

"Fra

that day hys legys all

Oysid hym Alysandyr the Fers to call."

So

effectually, indeed, did he succeed in crushing the inhabitants of Moray

that they were compelled to put to death Ladman, the son of Donald Bane,

who had instigated them to the attempt on his life. (Skene’s

Highianders, vol. i. p. 130.) The story that on this occasion the

traitors obtained admission to the king’s bed-chamber, and that he slew

six of them with his own hand, is an invention of Boece, and like many

other of his fables has obtained currency in Scottish history. Sir James

Balfour, in his Annals (vol. 1. pp. 6, 7.), has the following passage on

this attempt against the king: "The rebells quho besett him in the night

had doubtesley killed him, had not Alexander Carrone priuly carried the

king save away, and by a small boate saived themselves to Fyffe, and the

south pairts of the kingdome, quher he raissed ane armey, and marched

against the forsaid rebells, quhome he totally ouerthrew and subdued; for

wich grate mercey and preseruatione, in a thankfull retributione to God,

he foundit the monastarey of Scone, and too it gaue lies first lands of

Liffe and Innergourey, in AE

1114. About this tyme K. Alexander the I. reuardit for hes faithfull

seruice Alexander Carrone, with the office of standart bearir of Scotland,

to him and hes heirs for euer. He was called Scrimshour, becausse with a

drauen suord, in a combat, he had strucke the hand from a courtier; wich

surname of Scrinscoure, hes posterity to this day have kept." The name

signifies a hardy fighter. See SCRIMGEOUR, surname of; also,

DUNDEE, earl of.

During

the remainder of the reign of Alexander, the Highlanders acquiesced in his

occupation of the throne, he being now, even according to the Celtic laws,

the legitimate heir of Malcolm Canmore.

The principal feature in Alexander’s reign was his successful resistance

to the efforts made by the English prelates to assert a supremacy over the

church in Scotland. In 1109 when he first had occasion to nominate a

bishop to the see of St. Andrews, to which place the primacy had been

removed from Dunkeld, Alexander, with the approbation of his clergy and

people, named Turgot, the monk of Durham already mentioned as the

confessor and biographer of his mother the pious Queen Margaret. The

consecration of Turgot was, however, long delayed. The archbishop of York

pretended a right of consecrating the bishops of St. Andrews, but at this

time Thomas, elected archbishop of York, had not himself received

consecration. In consequence of a report that the bishop of Durham,

concurring with the Scottish bishops and the bishop of the Orkneys,

proposed to consecrate Turgot, in presence of the archbishop elect of

York, Anselm, archbishop of Canterbury, in alarm, despatched a letter to

the latter, informing him that consecration could not be performed by an

archbishop elect or by any one acting under his authority, and requiring

him to proceed to Canterbury to receive consecration himself. The Scottish

clergy on their part contended that the archbishop of York had no right to

interfere in the consecration of a bishop to the see of St. Andrews. While

the two archbishops were engaged in mutual altercations concerning

canonical order and the privileges of their respective sees, Alexander

entered into a negotiation with the English king, and an immediate

decision of the controversy was evaded by an ambiguous acknowledgment by

all parties, which, confessing the independency of the Scottish church to

be at least doubtful, seemed to prepare the way for its complete

vindication at a future time. At the request of Alexander, Henry, the

English king, enjoined the archbishop of York to consecrate Turgot, bishop

of St. Andrews, "saving the authority of either church." In that form

Turgot received consecration accordingly.

In

the discharge of his episcopal functions Turgot met with obstacles, which

induced him to form a resolution to repair to Rome to obtain the opinion

of the pope for regulating his future con duct; a journey which his death

soon after pre vented him from carrying into effect. What the nature of

these obstacles were, we are not informed, but as he perceived that he had

lost that influence which he formerly enjoyed in the time of Queen

Margaret, his spirit sunk, and in a desponding mood he asked and obtained

permission to retire to his ancient cell at Durham, where he died, 31st

August 1115.

A new

bishop of St. Andrews was to be appointed, and to avoid any interference

on the part of the archbishop of York, Alexander, soon after the death of

Turgot, addressed a confidential letter to Ralph archbishop of Canterbury,

who had succeeded Anselm, asking his advice and assistance for enabling

him to provide a fit successor to Turgot. In this letter he observed,

"That the bishops of St. Andrews were wont to be consecrated only by the

Pope or by the archbishop of Canterbury." "The expression," says Lord

Hailes "is flattering and artful. Alexander meant to relieve his kingdom

from the pretensions of the one archbishop without acknowledging the

authority of the other. He therefore left the right of consecrating

doubtful between the Pope and the archbishop of Canterbury, while, at the

same time, he seemed to place them both on a level." Eadmer, a monk of

Canterbury, had been fixed upon by Alexander to fill the vacant see, but

not receiving any answer to his proposal from the archbishop of

Canterbury, the king allowed the see of St. Andrews, the chief bishopric

in his kingdom, to remain vacant for many years. At length, in 1120, he

despatched a special messenger to the archbishop of Canterbury, with a

letter requesting the archbishop ‘to set at liberty’ Eadmer the monk, that

he might be placed on the episcopal throne of St. Andrews. The archbishop

consented that Eadmer should have liberty to accept the bishopric, and

with that view he asked and obtained the approbation of the English king.

In a letter to Alexander he said, "I send you the person whom you require

altogether free," and concluded thus, "To prevent the

inconveniencies which I foresee and dread, I would counsel you immediately

to send him back to be consecrated by me." On his arrival in Scotland,

Eadmer received the bishopric of St. Andrews on the 29th of June 1120. The

election was made by the clergy and people, with the permission of the

king; but on this occasion Eadmer neither received the pastoral staff nor

the ring from the hands of Alexander, nor did he perform homage. Next day

Alexander held a secret conference with him respecting the mode of his

consecration, when the king expressed his aversion at his being

consecrated by the archbishop of York. Eadmer, on his part, declared that

the church of Canterbury had, by ancient right, a pre-eminence over all

Britain, and he humbly proposed to receive consecration from that

metropolitan see. He found, however, that Alexander was as much opposed to

the pretensions of Canterbury as he was to those of York, and that he had

determined to free the Scottish church from dependence on any foreign see

but that of Rome. At Eadmer’s proposal Alexander is described as having

started from his seat with much emotion, and broken off the conference. He

commanded the person, one William a monk of St. Edmundsbury, who had

presided in the bishopric since the death of Turgot, to resume his

functions. At the expiry of a month, the king, at the request of his

nobility, sent for Eadmer, and with difficulty obtained his consent to a

compromise, by which Eadmer was to receive the ring from Alexander, to

take the pastoral staff from off the altar, as if receiving it of the

Lord, and then to assume the charge of his diocese. While the king was

absent with his army quelling some insurrection in the north, as the

Highlanders of the district of Moray, particularly at this time, gave

considerable opposition to his government, Eadmer was received into the

see of St. Andrews by the queen, clergy, and people.

Finding, however, that his own sovereign Henry, who was then in Normandy,

had, at the solicitation of the archbishop of York, written to the

archbishop of Canterbury prohibiting him from consecrating Eadmer, and

that Alexander had also received three letters from him requiring him not

to permit the consecration, the new bishop of St. Andrews resolved to

repair to Canterbury for advice. On hearing of his resolution Alexander

sent for him, and said, "I received you altogether free from Canterbury;

while I live, I will not permit the bishop of St. Andrews to be subjected

to that see." "For your whole kingdom," answered Eadmer, "I would not

renounce the dignity of a monk of Canterbury." "Then," replied the king

passionately,. "I have done nothing in seeking a bishop out of

Canterbury." It seems to have been Alexander’s design by soliciting a

bishop from the province of Canterbury, to obtain one who would have no

partiality for the see of York, and whom he hoped to win over to support

the independency of the Scottish Church; but the zeal of Eadmer for

Canterbury disappointed his views. Eadmer himself has given an ample

account of the contest between him and Alexander; and Lord Hailes, in his

Annals of Scotland, has generally followed his statements. The bishop

complains that after the last interview with the king, the latter became

rigorous and unjust, and would never afford him a patient hearing. He

refused to allow Eadmer permission to visit Canterbury "for the counsel

and blessing (meaning no doubt consecration) of the archbishop,"

contending that the church of Scotland owed no subjection to Canterbury,

and that Eadmer himself had been freed from all subjection to it.

In

the anomalous and uncomfortable position in which he found himself, Eadmer

was induced to ask the advice of a friend in England, one Nicholas, whom

Lord Hailes conjectures to have been an ecclesiastical agent, whose

business it was to solicit causes at the court of Rome. This man advised

him to obtain consecration from the Pope, under favour of the Scottish

monarch, and in the meantime to be generous and hospitable to the Scots,

as the best means of rendering them tractable and courteous. He concluded

his letter thus:

"I

entreat you to let me have as many of the fairest pearls as you can

procure. In particular, I desire four of the largest sort. If you cannot

procure them otherwise, ask them in a present from the king, who, I know,

has a most abundant store"—a remarkable evidence of the wealth and

magnificence of the Scottish monarchs at this time.

Eadmer, in his perplexity, also asked the advice of John bishop of

Glasgow, and of two monks of Canterbury, and the answer which they sent to

him seems to have determined him upon resigning the see. It was in these

terms: "If, as a son of peace, you desire peace, you must seek it

elsewhere than in Scotland. As long as Alexander reigns, it will be vain

for you to expect any friendly intercourse with him, or quiet under his

government. We are thoroughly acquainted with his dispositions: it is his

will to be everything himself in his own kingdom. He is incensed against

you, although he knows no reason for his resentment; and he will never be

perfectly reconciled to you, although he should see reason for a

reconciliation. You must, therefore, either abandon this country, or, by

accommodating yourself to its usages, dishonour your character and hazard

your salvation. Should you choose to depart from among us, you will be

constrained to restore the ring, which you received from the hands of the

king, and the pastoral staff which you took from off the altar. Without

complying with these conditions you will not be permitted to depart,

unless you could make to yourself wings and fly away." Eadmer consented to

restore the ring to Alexander, but with regard to the pastoral staff, he

declared that he would replace it on the altar, whence he had taken it,

‘and leave it to be bestowed by Christ,’ and that since force had been

used against him, he would relinquish the bishopric, and not reclaim it

during the reign of Alexander, ‘unless by the advice of the Pope, the

convent of Canterbury, and the king of England.’ Having thus, in effect,

resigned his see, Eathner was suffered quietly to leave the kingdom. He

afterwards addressed a long epistle to Alexander, in which, after setting

forth his pretensions to the bishopric, he added, in a tone of submission

which would have better become him at an earlier period: "I mean not, in

any particular, to derogate from the freedom and independency of the

kingdom of Scotland. Should you continue in your former sentiments, Twill

desist from my opposition; for, with respect to the king of England, the

arch-bishop of Canterbury, and the sacerdotal benediction, I had notions,

which, as I have since learned, were erroneous. They will not separate me

from the service of God and your favour. In those things I will act

according to your inclinations, if you only permit me to enjoy the other

rights belonging to the see of St. Andrews." The archbishop of Canterbury,

too, wrote Alexander, requiring him to recall Eadmer to Scotland; but

Alexander would not listen either to the solicitations, though humbly

enough expressed, of the one, or the requisition, however peremptory, of

the other. He was resolved to uphold the independence of the Scottish

church; and the undaunted spirit with which he maintained it throughout

the whole contest, would have been equally displayed, as Lord Hailes

justly remarks, in defence of the independence of his kingdom, had England

ever attempted to call it in question during his reign.

In

January 1123, about a year before Alexander’s death, the pretensions of

the archbishop of York were renewed, on the king procuring an English monk

named Robert, who was prior of Scone, to be elected bishop of St. Andrews.

The latter, however, was not consecrated till the fourth year of the reign

of David I. about five years afterwards, when Thurstin, archbishop of

York, performed the ceremony, under reservation of the rights of the Scots

church.

While thus successful in his resistance to the claims of supremacy on the

part of the metropolitan sees of York and Canterbury, Alexander, as was

usual in those days, evinced his devotion to the church by the ample

donations which he made to it. He bestowed upon the see of St. Andrews the

famous tract of land called the Cursus Apri, or Boar’s Chase, of which it

is not possible now to assign the exact limits; but "so called," says

Boece, "from a boar of uncommon size, which, after having made prodigious

havoc of men and cattle, and having been frequently attacked by the

huntsmen unsuccessfully, and to the imminent peril of their lives, was at

last set upon by the whole country up in arms against him, and killed

while endeavouring to make his escape across this tract of ground." The

historian adds, that there were extant in his time manifest proofs of the

existence of this huge beast; its two tusks, each sixteen inches long and

four thick, being fixed with iron chains to the great altar of St.

Andrews, having been placed there by the above named Bishop Robert, who

obtained the grant of the boar chase from Alexander, although not

consecrated bishop at the time it was bestowed. The legend that this

extensive tract of land was conferred in 370 by Hungus or Hergustus, a

Pictish king, who is unknown to history, is a monkish fiction utterly

unworthy of attention.

In 1123,

having narrowly escaped shipwreck near the island of AEmona, now called

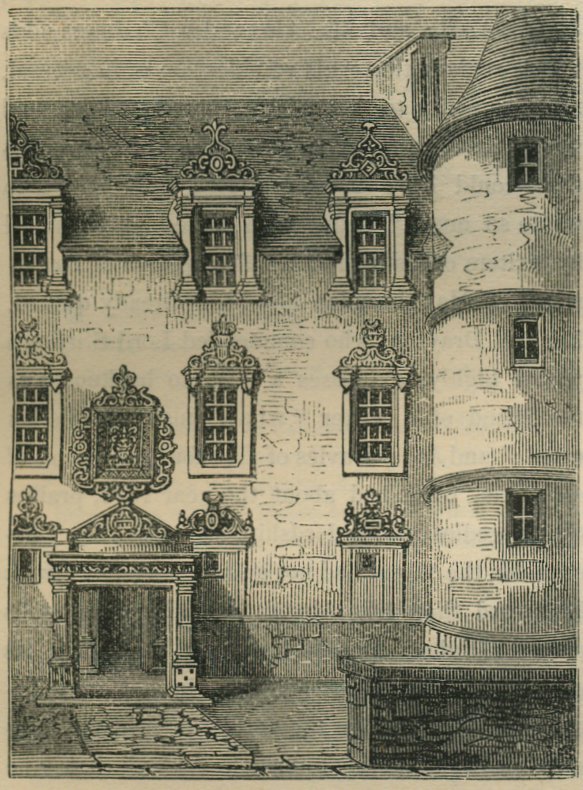

Inchcolm, in the Frith of Forth, Alexander built a monastery on that

island, of the ruins of which a woodcut is shown below.

The circumstances are thus related by Fordun:

"About

the year 1123, Alexander I. having some business of state which obliged

him to cross over at the Queen’s ferry, was overtaken by a terrible

tempest blowing from the south-west, which obliged the sailors to make for

this island, (AEmo na,) which they reached with the greatest difficulty.

Here they found a poor hermit, who lived a religious life according to the

rules of St. Columba, and performed service in a small chapel, supporting

himself by the milk of one cow, and the shelfish he could pick up on the

shore; nevertheless, on these small means he entertained the king and his

retinue for three days—the time which they were confined here by the wind.

During the storm, and whilst at sea and in the greatest danger, the king

made a vow that if St. Columba would bring him safe to that island, he

would there found a monastery to his honour, which should be an asylum and

relief to navigators. He was, moreover, farther moved to this foundation,

by having, from his childhood, entertained a particular veneration and

honour for that saint, derived from his parents, who were long married

without issue, until imploring the aid of St. Columba, their request was

most graciously granted." The monastery thus founded by Alexander was for

canons regular of St. Augustine, and was richly endowed by the grateful

and pious king its founder and patron. Being dedicated to St. Colm or

Columba, the island obtained the name thereafter of Inchcolm, which it

still retains. The king had previously brought a colony of canons regular

of St. Augustine from the monastery of St. Oswald at Nastley, near

Pontefract, in Yorkshire, and established them at Scone, the abbey of

which he had founded in 1114, and dedicated to the Holy Trinity and St.

Michael. This famous abbey, it is well known, enclosed the celebrated

coronation stone which was removed to England by Edward I., and is still

used at the coronation of the sovereigns of Great Britain at Westminster.

The abbey of Scone, also, thus founded by Alexander, witnessed the

crowning of the later Scoto-Saxon kings. By a royal charter he conferred

upon the monks of this abbey the right of holding their own court, and of

giving judgment either by combat, by iron, or by water; together with all

privileges pertaining to their court; including the right in all persons

resident within their territory, of refusing to answer except in their own

proper court. (Cartullary of Scone, p. 16.) This right of exclusive

jurisdiction was confirmed by four successive monarchs. In 1122, on the

death of his queen, Sybilla, who died suddenly at the castle of Loch Tay,

in Perthshire, on the 12th of June of that year, Alexander erected a

priory on a small island on Loch Tay, for the repose of his soul and that

of his consort. According to Spottiswood, this priory was a cell from the

monastery of Scone, and was founded by Queen Sybilla herself, but this is

evidently a mistake. Some very inconsiderable ruins of it still remain.

Alexander also granted various lands to the monastery of Dunfermline which

his father had founded, and is said to have finished the church. His queen

Sybilla also conferred lands on it.

Notwithstanding the rude condition of the inhabitants of Scotland at that

remote period, the personal state kept up by Alexander the First is

described as having been scarcely, if at all, inferior to that of his

brother-monarch of the richer country of England. It is well-known that in

the reign of his father, Malcolm Canmore, an unusual splendour was

introduced into the Scottish court by his Saxon consort, the good queen

Margaret, who not only encouraged the importation and use of rich

vestments from foreign countries, setting the example by being magnificent

in her own attire, but increased the number of attendants on the person of

the king, and caused him to be served at table on plate of gold and

silver. (Turgot’s Memoir of Queen Margaret.) Alexander I. seems to

have given to his public appearances, as sovereign, a degree of splendour

till then unknown in the northern end of the island. In his reign there

appears to have been a considerable intercourse between Scotland and the

East, as various oriental commodities and articles of Asiatic luxury were

imported into this country. It is related of this monarch, that, not

content with endowing the church of St. Andrews—which had been founded in

his reign by Turgot, its archbishop—with numerous lands, and conferring

upon it various immunities, as an additional evidence of his devotion to

the blessed apostle St. Andrew, after whom the see was called, he

commanded his favourite Arabian horse to be led up to the high altar, his

saddle and bridle being splendidly ornamented, while his housings were of

a rich cloth of velvet. The king’s body armour, of superb Turkish

manufacture, and studded with jewels, with his spear and his shield of

silver, were at the same time brought by a squire; and these, along with

the horse and his furniture, the king, in the presence of his prelates and

barons, solemnly devoted and presented to the church. The housings and

arms were shown in the days of the historian who has recorded the event.

(Extract from the Register of the Priory of St. Andrews, in Pinkerton’s

Dissertation, Appendix, vol. i. p. 464. Winton, vol. i. p. 286.

See also Tytler’s History of Scotland, vol. ii. p. 198.)

The rising commerce of the country in those early times was much aided and

advanced by the settlement, in the districts contiguous to the Borders, of

numbers of Flemish merchants, who, during the reign of Alexander,

gradually spread into Scotland, and at a later period, namely, in the

reign of David the First, were found in all the towns along the east

coast, and even in the western parts of the kingdom, wherever traffic

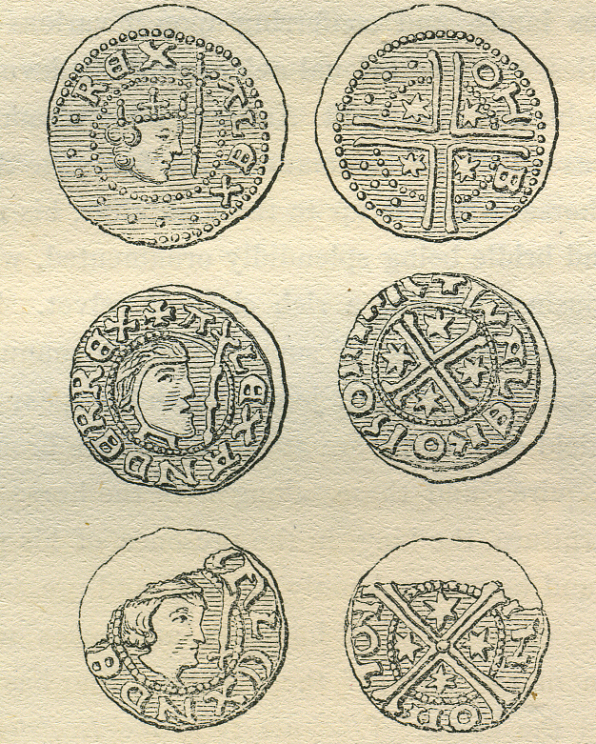

could be safely and profitably carried on. The money in circulation in

Scotland at that period appears to have been of silver only. Indeed, down

to the reign of Robert the Second, the gold coinage of England, then

current in Scotland, seems to have been the only gold money in use. Of the

early silver money of Scotland, the most ancient specimens yet found are

the pennies of Alexander the First, which are now extremely rare. They are

described as being of the same firmness, weight, and form as the

contemporary English coins of the same denomination, and down to the time

of Robert the First, the money of Scotland was precisely of the same value

and standard as that of England. (See Ruddiman’s Introduction to

Anderson’s Diplomata, pp. 54, 55.—Tytler’s history of Scotland,

vol. ii.. p. 264.] The annexed engraving of the silver pennies (left)

of Alexander I is from Anderson’s Numismata.

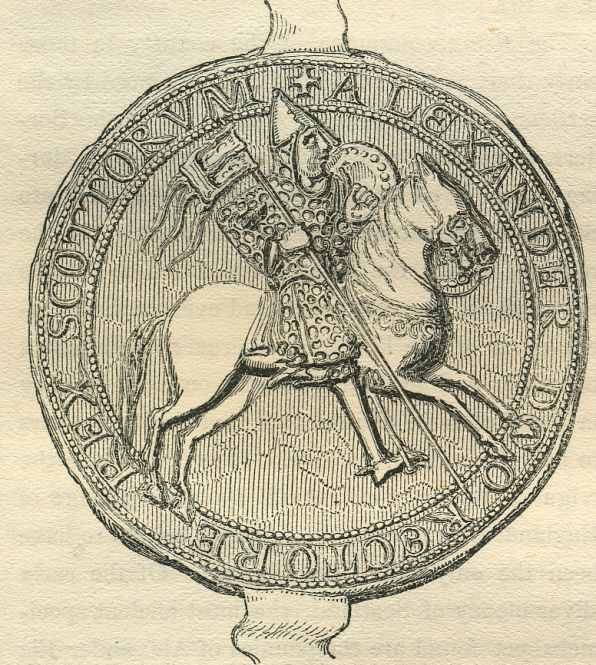

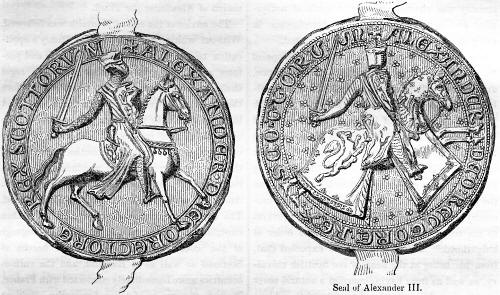

Annexed (at right) is a seal of Alexander I in which he is

represented fully cased in the armour of that period.

Here we find the scaled mail-coat composed of mascles, or lozenged pieces

of steel, sewed upon a tunic of leather, and reaching only to the mid

thigh. The hood is of one piece with the tunic, and covers the head, which

is protected with a conical steel cap, and a nasal; the sleeves are loose,

so as to show the linen tunic worn next the skin, and again appearing in

graceful folds above the knee; the lower leg and foot are protected by a

short boot, armed with a spur. The king holds in his right hand a spear,

to which a pennoncelle, or small flag, is attached, exactly similar to

that worn by Henry the First; the saddle is peaked before and behind; and

the horse on which he rides is ornamented by a rich fringe round the

chest, but altogether unarmed. (Seal in the Diplomata Scotice,

plate 7. Tytler’s History of Scotland vol. ii. p. 360.)

Alexander the First died at Stirling on the 27th of April 1124, in the

seventeenth year of his reign, and leaving no issue was succeeded by his

youngest brother, David. He was interred before the high altar at

Dunfermline, near to his father. During his reign, as during that of his

brother and predecessor Edgar, the laws, institutions, and forms of

government, except in the Gaelic portion of the kingdom, were purely

Saxon; and to this particular epoch in our nation’s history, may be traced

the earliest existence in Scotland of some of the great officers of state,

who after that period discharged some of the more important functions of

the government, as the chancellor, the constable, &c. The former was the

most intimate counsellor of the king, and generally the witness to his

charters, letters, and proclamations, and the latter, an office of

undoubted Norman origin, was the leader of the whole military power of the

kingdom. The first appearance in Scotland of the now ancient office of

sheriff is also referred to this reign, although the division of the

country into regular sheriffdoms did not take place till a much later

period. "During the reigns of Edgar and Alexander I.," says Skene, "the

whole of Scotland, with the exception of what had formed the kingdom of

Thorfinn (during the Norwegian conquest consisting of the Orkneys, the

Hebrides, and a large portion of the Highlands), exhibited the exact

counterpart of Saxon England, with its earls, thanes, and sheriffs, while

the rest of the country remained in the possession of the Gaelic Maormors,

who yielded so far to Saxon influence as to assume the Saxon title of

earl." (History of the Highianders, vol. i. p. 128.) The personal

character of Alexander was bold and energetic, and his disposition fiery

and impetuous. Strenu ous in maintaining his authority, he had, early in

his reign, applied himself to repressing the disorders and insurrections

which were continually breaking out in the Celtic portion of his

dominions, and his ardent temper and daring spirit contributed not a

little to his success in overawing the turbulent inhabitants of the north,

and reducing them to submission. The boldest chieftains are said to have

trembled in his presence, and the epithet of ‘Fierce’ attached to his name

seems to have arisen from the energy which he at all times displayed, and

which was necessary for reclaiming the Scots from that savage barbarism

into which they had relapsed under Donald Bane. Although terrible to the

rest of his people, Alexander is described by Aidred, as being humble and

courteous to the clergy, "not ignorant of letters," liberal even to

profusion, and kind and benevolent to the poor.—Hailes’ Annals of

Scotland, vol. i., and the authorities quoted in the preceding article.

ALEXANDER II.,

king of Scotland, the fourth in succession from the subject of the

foregoing memoir, to whom he stands in the relation of great grand-nephew,

was born at Haddington 24 Aug., 1198. He was the only legitimate son of

William surnamed the Lion, his predecessor on the throne. His mother,

Ermangarde, was daughter of Richard Viscount de Beaumont, a descendant

from Henry I. of England, through his mother, a natural daughter of that

monarch. He succeeded his father December 4, 1214, being then only sixteen

years of age, and was crowned at Scone on the 20th of the same month.

Some years before the death of William his father, that monarch had been

engaged in warlike demonstrations against England, followed, (in 1209,) by

a treaty of a singular character, of which the provisions have not yet

been clearly ascertained. It appears that during the troubles in which

John—the monarch who then sat upon the English throne—was involved, (in

consequence of disputes with the head of the church and the

dissatisfaction of his barons, which finally resulted in the concession by

him of Magna Charta,) William—conceiving the opportunity to be

favourable—took occasion to demand that the counties of Northumberland,

Cumberland, and Westmoreland, (which until about the middle of the reign

of Henry II. had constituted the county or province of Northumbria,

and under that designation had been held during the latter part of the

reign of his grandfather David I., by the eldest son of that

monarch, the father of William, as a fief of the English crown, but on the

death of that monarch had been resumed by Henry II.,) should be restored

to the Scottish nation. How far that claim—one of the vexed questions of

Scottish history—was founded in right, does not properly fall to be

considered in this biography, but will be treated of in that of Malcolm

IV., the brother of William, on whose accession these counties were

restored to Henry, and to which therefore we refer. We may, however,

remark,—unwilling as we are to yield to any one in the assertion of the

just rights of Scotland,— that there does not appear in the circumstances

any warrant for assuming—as William then did, and as Scottish writers have

hitherto done—that the intrusting of the government of these counties by

Stephen in February 1139 to Prince Henry, son of David—as an individual

lordship for which he rendered homage—can be construed into permanent

cession of their possession from the English to the Scottish crown. It may

more probably be inferred as done in guarantee of the fulfilment of the

solemn engagement then entered into with David by Stephen, that the crown

of England—usurped by him—should at his death descend to Henry,

grand-nephew of David,—son of the empress Matilda his sister’s daughter

the rightful heiress,—on whose behalf alone it was that that wise and

righteous prince had professed to take up arms. The retention in his own

hands by the English king, during the entire period of their government by

the heir to the Scottish throne, of the commanding strengths of

Bamborough, Norham, and Newcastle on Tyne, (the two former situated near

the Scottish border,) and the omission of all reference to the

circumstance of the supposed cession on the part of English historians,

gives additional probability to this aspect of the transaction. Its

resumption, therefore, on the fulfilment of that stipulation towards the

close of the reign of David, may in this view of the matter have involved

no injustice on the part of the English monarch, and appears to have been

peacefully acquiesced in by Malcolm, the then reigning king. In the

history of the two kingdoms of that period, however, it will frequently be

found that the occasion of distraction or civil contest on the part of

the one was frequently embraced, to press to an issue assumed or disputed

claims on the part of the other, and the fearful state of matters which

then obtained in England—placed as it was under a papal interdict, the

public services of religion suspended, the rites of interment withheld,

the prelates banished, and the nobles insulted—presented an opportunity

too tempting to be withstood by William, for making a demand which, if

yielded to, would at once aggrandize his kingdom, and avenge his long

captivity. Nor is there wanting, in the earlier history of that monarch

himself, more than one incident to illustrate the truth of the foregoing

remark.

In

order to understand the position of the parties, however, on the occasion

of the conclusion of this treaty, it is proper to observe that, according

to the English historians, John,—notwithstanding the dangerous situation

in which he stood, and the loss of reputation he had sustained by

acquiescing in the conquest of the English provinces in France,—appears,

on becoming aware of the military preparations of William, to have

manifested a degree of energy unusual to him, and to have resolved to do

some act that would give a lustre to his government. He is represented by

them as having been successful in his military enterprises in Scotland, as

also in others which he undertook against the Irish and Welsh. It was in

these circumstances, therefore, that by the treaty in question, the king

of Scotland bound himself to pay to John fifteen thousand merks (supposed

to be equivalent to one hundred and fifty thousand pounds sterling of our

present money) in two years, by four equal payments, "for procuring his

good will (benevolentia), and for fulfilling certain conventions

between them," contained in a charter which has not been preserved. For

the performance of this treaty William gave John hostages. He likewise

delivered his two daughters, Margaret and Isabella, to the king of England

to be educated at his court, and "that they might be provided by him in

suitable matches," but not to be considered as hostages. About thirty

years thereafter it was stated in the English parliament that the

conditions of the charter referred to were that the two Scottish

princesses should be married to king John’s two sons, and that the money,

together with a renunciation of his claim to the northern counties, was

given by William as their marriage portion. Hubert de Burgh, the

justiciary of England, who married the princess Margaret, positively

denied, however, all knowledge of any such condition as the former; while

some Scottish writers subsequently founded on its non-fulfilment a

supposed claim for the restitution of the latter. [See Life of William the

Lion, post.]

Shortly after Alexander came to the throne affairs in England became

involved in a still greater degree of confusion than before. John,

perfidious and perjured as tyrannical, had violated the provisions of

Magna Charta, set his barons at defiance, and threatened alike to crush

the liberties of the country and their power. In this emergency, they

decided to renounce their allegiance to him, and sent a deputation to

offer the crown of England to Louis, son of the king of France. At the

same time such of them as held possessions in the northern counties

applied to Alexander, and offered to put him in possession of these

districts as the consideration for his aiding them against their

oppressor. Although so young, Alexander was not unwilling to avail himself

of the proposal, and an agreement was accordingly entered into to that

effect. In accordance with this agreement, Alexander with an army marched

into Northumberland, and on the 18th of October 1215, he received the

homage of the barons of that county at Felton castle. The castle of Norham

was besieged by him for forty days, during which time Eustace de

Vesci,—one of the principal barons of the northern counties, who had made

himself conspicuous by his opposition to John,—gave him investiture of the

county of Northumberland by livery and sasine. The intelligence of these

negotiations, however, again stirred up John to unwonted activity, and he

resolved to crush the northern invasion before Louis should arrive in

England. Accordingly, immediately after Christmas, whilst a deep fall of

snow lay on the ground, at the head of a large force, consisting

principally of foreign mercenaries, he advanced into Yorkshire and

Northumberland, devastating the estates of the confederated barons, and

burning and slaying wherever he came. All the castles and towns they could

take were given to the flames, King John himself setting the example, as

he fired with his own hands in the morning the house in which he had

rested the preceding night.

On the

approach northward of John, Alexander raised the siege of Norham, and

retired within his own dominions. The English barons accompanied him, and

those of the northern counties did homage to Alexander at the abbey of

Melrose on the 15th January 1216. (Chonicle of Melrose, p. 190.]

John with his mixed and savage host of foreign soldiery followed, burning,

in their march, the towns of Werk, Morpeth, Alnwick, Mitford, and

Roxburgh. After storming Berwick they entered Scotland, torturing,

plundering, and massacring the inhabitants in their way. The towns of

Dunbar and Haddington were likewise burnt to the ground. John was

determined to have vengeance on Alexander for the assistance which he had

given to the patriotic barons who had taken up arms against him. "We will

smoke," he said, "the little red fox out of his covert." From this laconic

description of him we may infer that Alexander the Second was both

diminutive in stature and ruddy in complexion. John pursued his

devastating course as far as Edinburgh, but was soon obliged to withdraw

from a country which his troops had ravaged so completely that it no

longer afforded them subsistence. In his retreat, his forces burnt the

priory of Coldingham, which had been founded in the year 1098 by Edgar

king of Scotland, and the town of Berwick; John himself, as was his usual

practice, giving the example to his brutal soldiery by setting fire to the

house in which he had lodged.

For the priory of Coldingham thus ruthlessly consumed by John’s savage

followers, Alexander, like all the rest of the Scottish kings since the

time of Edgar its founder, had a great veneration. He had not only

confirmed the charters which his predecessors had granted to it, but

exempted the prior and his monks from a sum of twenty merks that they had

been in the custom of paying yearly to his exchequer, under the name of

wattinga,—a tax which appears to have been levied from the landholders

in Scotland for the purpose of erecting and maintaining in repair the

government fortresses. He also issued a writ to Robert de Bernham, the

mayor, and to the bailiffs of Berwick, enjoining them to allow free

passage to foreign merchants, when on their way to the priory to purchase

the wool and other commodities belonging to the monks, and prohibiting

every one from seizing any property, moveable or unmoveable, belonging to

the convent, within the barony or lordship of Coldingham, for debt on

forfeiture. Besides these immunities, he released "the twelfth village of

Coldinghamshire, or that in which the church is founded," from the aids

and military service which had formerly been exacted. It was not likely

therefore that he would allow John’s destructive march to pass without

taking dreadful reprisals.

Accordingly, in the month of February following this inroad, Alexander in

his turn wasted the western marches with fire and sword and penetrated

into Cumberland. Some of the undisciplined Scots, by which name the

monkish historians distinguish the Highlanders in his army, plundered and

burnt the abbey of Holmcultram, in revenge for the destruction of the

priory of Coldingham by the English. These reverend chroniclers relate

with apparent delight that two thousand of the Scots, on their way home

with their booty, were drowned in the flooded current of the river Eden,

as a judgment for their sacrilegious violation of a holy house. After a

temporary retreat into his own territories, Alexander invaded Cumberland a

second time, in the month of July, with all his army, except the

Highlanders, whom he had chastised and dismissed (Chron. Mel., p.

191), and on the 8th of August, he took possession of the city of

Carlisle. The castle, however, held out against him. He then marched

southwards quite through England to Dover, to join Louis, the son of the

king of France, who by this time had arrived in England. In his progress

Alexander assaulted Bernard castle, the seat of the Baliol family, then

held by a garrison for John. Eustace de Vesci, who had given him

investiture of Northumberland at Norham castle, was slain there. On

arriving at Dover he found Louis besieging the castle, and as the English

barons had done, he did homage to that prince for all his lands in

England, and particularly for the counties of Northumberland, Cumberland,

and Westmoreland, which were then granted to him by charter. (Rymer’s

Foedera, tom. ii. p. 217.) This he might very well do, for the French

prince Louis had not only been offered and had accepted the crown of

England, but actually had a claim to it in right of his wife. On this

occasion Louis, on his part, swore that he would not conclude a separate

peace, an oath which he was soon compelled to violate. On his return

homeward Alexander met with some obstruction in passing the Trent, the

bridge at Newark having been broken down by the army of King John, who

expired at the castle of Newark, 19th Oct. 1216.

Some time before this (May 15, 1213) John had been reduced to the unworthy

expedient of surrendering his dominions into the hands of the Pope, and of

consenting to hold them henceforward only as his vassal, as a means of

escaping from the consequences of the papal interdict, and threatened

excommunication. When compelled by his barons and clergy (June 19, 1215)

to sign the Great Charter, inwardly resolving to violate its provisions,

he, as one means of effecting this, laid a statement of the matter, with a

complaint of the violence imposed upon him, before his feudal lord, the

supreme pontiff, who issued a bull, absolving him from his oath, annulling

the charter, and prohibiting the barons from exacting the observance of

it, on pain of excommunication. Strange to say, the English primate

refused to obey the pope in publishing the sentence, and though suspended

on account of this proceeding, and a new and particular sentence of

excommunication was issued by name against the principal barons,—including

not only the French prince Louis, but Alexander and his whole army, and

the entire realm of Scotland,—the nobility and people, and even the

clergy, of both kingdoms adhered to the combination against him, and so

little zeal in the matter was manifested by the clergy of Scotland, that

nearly a twelvemonth elapsed before it was published there. (Chron.

Melrose, 192. Fordun, ix. 31.)

Although Alexander, as already stated, had taken the town of Carlisle, the

castle held out, and was besieged by him unsuccessfully. While engaged in

this siege, a portion of the army of Prince Louis was entirely defeated in

the streets of Lincoln, 19th May 1217, the count de Perche, its

commander-in-chief, being killed, and many of the chief commanders taken

prisoners. On the news of this defeat, Prince Louis, who was still

occupied with the siege of Dover, proceeded to London, where he learned

the further defeat of a fleet bringing him reinforcements from France, and

the general defection of the barons, as they had by this time become

suspicious of his intention. In the general turn which men’s dispositions

had taken, the excommunication denounced by the legate failed not now to

produce a mighty effect on them, and they were easily persuaded to

consider a cause as impious, which had hitherto been unfortunate, and for

which they had already entertained an insurmountable aversion. Seeing his

cause to be desperate, Louis now began to be anxious for the safety of his

person, and entered into a negotiation with the earl of Pembroke,

protector of the realm of England,—Henry the Third, the son and successor

of King John, being then a minor,—and a peace was concluded, Louis

stipulating for a full indemnity to the English of his party—with a

restitution of their honours and fortunes, together with the free and

equal enjoyment of those liberties which that wise noble had guaranteed in

the name of the prince to the rest of the nation—and formally renouncing

his pretensions to the crown of England. That Louis might be reconciled to

the holy see, he did penance by walking barefooted to the legate’s tent,

in presence of both armies. He then departed with all his foreign forces

to France.

On

receiving intelligence of these events, Alexander, who was then on his

march into England, made overtures of peace to the young king Henry III.,

and after some time spent in negotiation, a treaty was concluded between

them. He then yielded up the town of Carlisle to the English, and in an

interview which he had with King Henry at Northampton, he did homage to

him,—but for his English possessions only, as Scottish writers allege,—and

returned into Scotland. (Chron. Mel. 192, 194, 195. Fordun

ix. 31.)

Alexander now sought to be reconciled to the Pope, and having procured a

safe conduct from England, he proceeded to Tweedmouth, on the English side

of the Border, and there met the archbishop of York and the bishop of

Durham who had been delegated by the Pope’s legate for the purpose, and

received absolution from their hands, 1st December 1217, without being

called upon to perform the ignominious penance which generally preceded

absolution. Some days thereafter the delegates also removed the ban of

excommunication from Alexander’s mother, queen Ermengarde. The sentence

was also removed from the whole body of the Scottish nation, except the

prelates and the clergy, who had become obnoxious by reason of their

reluctance to publish the bull.

In

the spring of 1218, William, prior of Durham, and Waiter de Wisbech,

archdeacon of York, traversed Scotland, "from Berwick to Aberdeen," for

the purpose of absolving the Scottish clergy from the sentence of

excommunication. While upon this tour, on arriving at a town they summoned

the clergy to attend them, and having required them to swear allegiance to

the papal legate, and to make a candid confession of all matters

concerning which they were asked, they absolved them, standing barefoot

before the doors of their churches and abbeys. The commissioners were very

sumptuously entertained, and their favour was courted by large bribes of

money, and many presents. (Ridpath’s Border History, p. 127.) On

their return south they halted at the abbey of Lindores, where the prior

of Durham was nearly suffocated with smoke, a fire having broken out in

the chamber where he slept, through the carelessness and rioting of those

who had the charge of the wine, "his chamberman," as Balfour pithily says,

"being verey drunke." He died at Coldingham priory, which appears to have

been partially restored after its burning by King John in 1216. The

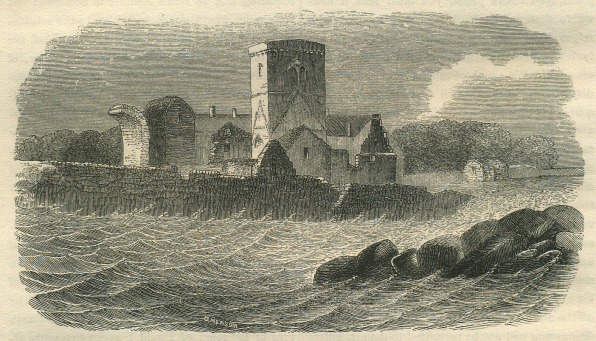

woodcut at right is of the ruins of this celebrated priory.

Against these proceedings the king appealed to Rome, while the clergy

themselves sent a deputation of three bishops to the Pope. A judgment was

obtained in their favour, which declared that the legate had exceeded his

powers, and not only was absolution granted by Pope Honorius, but the

liberties and privileges of the Scottish church were confirmed (Fordun

a Goodal, vol. ii. pp. 40, 42.) For this favour one of the causes

mentioned is the respect and obedience which Alexander had manifested to

the papal see. This concession on his part in a few years thereafter (in

1225) led to one of still greater importance. The Scottish clergy having

represented to the Pope, that from the want of a metropolitan they could

not hold a provincial council, he authorized them to hold a general

council of their own authority. Of this permission they were not slow to

take advantage, and having assembled under its sanction, they drew up a

distinct form of proceeding, by which the Scottish provincial councils

were in future to be held; instituted the office of Conservator Statutorum,

and continued to assemble frequent provincial councils, unfettered

by the intervention of any foreign superior.

By one article of the treaty of peace concluded in 1217 between Alexander

and Henry, it was stipulated that the king of Scotland should marry the

princess Joan, the eldest sister of the king of England; and their

nuptials, after some delays, occasioned by the detention of the princess

in France, were celebrated on the 25th of June 1221. The princess Joan, on

her marriage, was secured in a jointure of one thousand pounds of land

rent. (Faedera, tom. ii. p. 252.) Lord Hailes says, "The jointure

lands were Jedworth, Lessudden, Kinghorn, and Crail. Any deficiencies were

to be made good out of the castles and castellanys of Ayr, Rutherglen,

Lanark, and the rents of Clydesdale, Kinghorn and Crail were, at that

time, part of the jointure lands of the queen-dowager."

The peace with England and the marriage of Alexander to the English king’s

sister put a stop to all hostilities between the two nations for several

years, and introduced a friendly intercourse between the two royal

families, now so nearly related, which for a long time continued

uninterrupted. The king and queen of Scotland made frequent visits to the

court of England; where they were nobly entertained, and received many

valuable proofs of friendship from King Henry. The alliance with England

was still farther strengthened by the marriage of Alexander’s two sisters,

the princesses Margaret and Isabella, who had been sent to England in the

preceding reign, to English barons of great power and influence, namely,

Margaret, soon after her brother’s marriage in 1221, to the celebrated

Hubert de Burgh, justiciary of England, and Isabella, in 1225, to Roger

Bigot, eldest son of Hugh, Earl Bigot. (Fordun, ix. 32, 33.

Faedera, i. 227, 228, 374. Matth. Paris, 216.) For providing

portions for his sisters, Alexander, in 1224, levied an aid of ten

thousand pounds upon the nation. This grant is stated by some of our

Scottish writers, in the loose manner in which they are accustomed to

write of events which took place at that remote period, to have been

authorized by Alexander’s parliament; while, on the contrary, it was

imposed by the simple order of the king himself, without the slightest

appearance of a meeting of the three estates, or even of the council of

the king. Such a thing as a parliament was then unknown in Scotland. The

first meeting, indeed, of what may be termed one did not take place till

1289, fully sixty-five years later, when, after the death of Alexander

III., the estates of the kingdom, that is, the five guardians or regents,

ten bishops, twelve earls, twenty-three abbots, eleven priors, and

forty-eight barons, calling themselves the community of Scotland, although

no representatives of the burghs or of the people were among them, met at

Brigham, now Birgham, an obscure village in Berwickshire, to take into

consideration the proposal for a marriage between the prince of Wales, the

son of Edward the First of England, and the young queen Margaret of

Scotland, called "the Maiden of Norway." When Fordun (vol. ii. p. 34)

asserts that Alexander the Second, immediately after his coronation, held

his parliament in Edinburgh, in which he confirmed to the chancellor,

constable, and chamberlain the same high offices which they had filled at

his father’s death, the word parliament so used may be held only to mean

an assembly of the court, or the council of his nobles and great officers

of the crown, and not a parliament, or even convention of estates, in the

modern meaning of the word. (See Tytler’s History of Scotland, vol.

ii. sect. 3.)

Anciently the barons of the realm, with the crown vassals and higher

clergy, constituted the communitas regni, which formed the

parliament, as Mr. Skene terms it, of all Teutonic nations. To this body,

composed of Celtic, Norman, and Saxon dignitaries and landholders,

belonged the duty of counselling the monarch, and expressing the wants and

wishes of the nation, without the great mass of the people having either a

voice or a will in the matter, the principle of elective representation

being altogether unknown to them. But there was another and even a higher

body in the state, independent of the communitas, whose peculiar

privileges were only exercised on great and rare occasions, namely, when

there was a vacancy in the throne. This was the Septem Comites .Regni

Scoticae, "the seven earls of Scotland." Until very recently, the

existence of such a corporate body in the state seems to have been

entirely unknown. To Sir Francis Palgrave belongs the merit of having made

the discovery of a fact of so much importance to the right understanding

of the history of Scotland. It is proved, he says in his ‘Treasury

Documents illustrative of Scottish History,’ published in 1837, that

"there existed in the ancient kingdom of Scotland, a known and established

constitutional body denominated ‘the seven earls of Scotland,’ possessing

privileges of singular importance as a distinct estate in the realm,

severed equally from the other earls, and from the body of the baronage."

These seven earls as a body derived their functions from the old Celtic

constitution of the country, ancient Albania, or Scotland, north of the

friths of Forth and Clyde, being divided into seven great provinces or

governments. The Pictish names of these provinces were Flv, Cait, Fotla,

Fortrein, Circui, Ce, and Fidach, corresponding with, according to

Geraldus Cambrensis, Fife, Caithness, Atholl and Garmorin, Stratherne and

Menteth, Angus and Mearns, Moray and Ross, and Marr and Buchan. Three of

these were provinces of the Southern Picts, namely, Fife, Stratherne and

Menteth, and Angus and Mearns; the other four belonged to the northern

Picts. These seven provinces formed the kingdom of the Picts or Scotland

proper, previous to the ninth century. The Scottish conquest, in 843,

having added to it Dalriada, which afterwards became Argyle, and Caithness

having towards the end of the same century fallen into the hands of the

Norwegians, the former was after that period substituted for the latter,

and the earl of Argyle instead of the earl of Caithness was numbered among

"the seven earls." The Pictish nation consisted of a confederacy of

fourteen tribes spread over the seven provinces named, in each of which

one of the seven superior chiefs ruled under the Celtic name of maormor.

In the reign of Edgar they assumed the Saxon title of earl, and their

territories were exactly the same with the earldoms into which the north

of Scotland was afterwards divided.

In

the appendix to the first volume of Mr. Skene’s valuable ‘History of the

Highlanders,’ will be found a clear account of the ‘seven ancient

provinces of Scotland,’ over which the seven earls presided. It was the

privilege of these seven superior chiefs, by immemorial custom, as a

peculiar estate in the realm, to appoint a king, whenever there was a

vacancy, and to invest him with the royal authority, a right which they

appear to have exercised after the Pictish kingdom had ceased to exist.

Among the other documents preserved in the Treasury, illustrative of

Scottish history, which the researches of Sir Francis Palgrave have

brought to light, is a roll containing the appeal of the seven earls in

1290 to the authority and protection of Edward I. and the English crown,

against William Fraser, Bishop of St. Andrews, and John Comyn, Lord of

Badenoch, the Scottish regents, during the interregnum that succeeded the

death of the Maid of Norway, on the ground that the regents were

infringing or intending to infringe this their constitutional franchise;

which appeal, it is now understood, led to the famous summons of the

English monarch that the Scottish nobility and clergy should meet him at

Norham in the English territories, on the 10th of May 1291, to decide upon

the claims of the various competitors to the Scottish crown. Having given

this explanation, which will form a key to much of what would be otherwise

unintelligible or obscure in the early history of Scotland, we resume the

regular narrative.

The external tranquillity which Scotland enjoyed after the peace with

England and the marriage of Alexander to the sister of the English king,

allowed Alexander leisure to suppress some dangerous insurrections that

had broken out at home. In 1221, Somerled, a grandson of the celebrated

lord of the Isles of that name, possessed the whole district of Argyle,

which was then much more extensive than the modern Argyleshire, and having

that year risen in rebellion, the king collected an army in Lothian and

Galloway, and sailed for Argyle, intending to disembark his force, and

penetrate into the interior of the country, but his ships were driven back

by a tempest, and forced to take refuge in the Clyde. Alexander, however,

was not discouraged, but resolved to proceed into Argyle by land. With a

large army, which he had summoned from every quarter of his dominions, he

made himself master of the whole of the insurgent district, and compelled

Somerled to flee to the Isles, where, about eight years afterwards, he met

a violent death. Winton says,

"De

king that yhere Argyle wan

Dat rebell wes till hym befor than

For wythe hys Ost thare in wes he

And Athe’ tuk of thare Fewte,

Wythe thare serwys and their Homage

Dat of hym wald hald thare Herytage,

But of the Ethchetys of the lave

To the Lordies of that land he gave."

The estates of those who fled were bestowed on the principal men of the

king’s army as a reward for their having joined the expedition; but

wherever the former vassals of Somerled submitted and were received into

favour, they became crown vassals, and held their lands in chief of the

crown. The district in which the forfeited estates were, was farther

brought under the direct jurisdiction of the government, by being,

according to the invariable policy of Alexander II., erected into a

sheriffdom by the name of Argyle, the first sheriffdom bearing that name,

while the ancestor of the Campbells was made hereditary sheriff of the new

sheriffdom. (Skene’s History of the Highlanders, vol. ii. p. 46.)

The whole of the then northern Argyle, now part of Inverness-shire, was

bestowed on the earl of Ross, as a reward for the assistance which he had

rendered to the king on this and a former occasion.

Besides suppressing this insurrection in Argyle, Alexander was about the

same time called upon to punish some disturbances of an alarming kind

which had broken out in Caithness. In 1222, Adam bishop of Caithness was

cruelly burnt to death in his own palace. He had proved himself extremely

rigorous in enforcing the demand for tithes, leading the poor people’s

corn, as Balfour says, "too avariciously," and when the people of his

diocese had assembled to consider what was to be done under the

circumstances, one of them exclaimed, "short rede, good rede, slay we the

bishop," meaning, "Few words are best, let us kill the bishop." The

persons assembled unfortunately were too excited to pause or reflect—they

followed the cruel advice, thus rashly given, but too literally. Rushing

with eagerness to the bishop’s house, they furiously assaulted it, set it

on fire, and burnt the unhappy prelate in the flames of his own palace,

with a monk who attended him, named Serlo. Some of the bishop’s servants

applied to the earl of Orkney and Caithness to protect their master from

the fury of the mob; he answered that if the bishop came to him he would

be sure of protection, but did not offer to go to his assistance.

Alexander received intelligence of this cruel action when he was upon a

journey towards England. He immediately turned back, marched into

Caithness with an army, and put to death four hundred of those who had

been concerned in the murder of the bishop. The earl of Orkney who might

have prevented the catastrophe but did not, was believed to have favoured

the conspiracy, but him the king pardoned, as he had no actual hand in the

crime. He had to pay, however, a large sum of motley, and give up the

third part of his estate. Balfour says that in the following year, while

Alexander was keeping his birth-day at Forfar, the earl of Orkney with a

good sum of ready money redeemed the third part of his estate from the

king, but on his return home he was murdered in his own castle, which was

afterwards burnt, in imitation and revenge of the, bishop’s fate. This

event, however, according to the chronicle of Melrose (p. 201) quoted by

Lord Hailes, did not take place till 1231.

In

the life of Alexander I. allusion has been made to the peculiar law of

succession which prevailed amongst the Pictish, or Gaelic tribes. (See p.

54, ante.) This law of Tanistry, as it was called, provided that on

the death of a chief, the brother, or "he of the blood who was nearest,"

succeeded to the chiefship, to the exclusion of females and even sons, the

brother being considered one degree nearer the original founder or

patriarch of the race than the son, and if the person who ought to succeed

was under fourteen years of age,—the ancient Highland period of

majority,—his nearest male relation became chief, and continued so during

his life, the proper heir inheriting the chiefship only at his death. (Skene’s

History of the Highlanders, vol. i. pp. 160, 161.) The establishment

of such a law originated primarily, there cannot be a doubt, in the

natural anxiety to avoid minorities in a tribe or cIan, so that it might

always have a competent leader in war, a principle which, however much

opposed to the feudal notions of later times, flowed naturally from the

patriarchal constitution of society in the Highlands, being peculiarly

adapted to the circumstances of a people whose warlike habits and love of

military enterprise, as well as addiction to armed predatory expeditions,

demanded at all times a chief of full age and every way qualified to act

as their leader and commander.

As,

however, the Highlanders adhered strictly to succession in the male line

and according to the lineal descent from the common ancestor, or founder

of the tribe, any infraction of this rule was often productive of the most

serious outbreaks and insurrections. This was remarkably the case in the

old rnaormordom or province of Moray, which, at the period when Alexander

the Second ascended the throne, included not only what now forms the

counties of Elgin and Nairn, but a considerable part of Banffshire and

nearly the half of Inverness-shire. This was always one of the most re

bellious portions of the kingdom; and although the tribes of Moray, in

common with the rest of the Highlanders, recognised in Alexander I. and

his successor David I. the legitimate heirs of Malcolm Canmore, they were

never without a pretext for disturbing the country. After the suppression

of their attempt at insurrection early in the reign of the former, when

Angus referred to (p. 54) as of the family of Macbeth,—whom Skene with

reason supposes to be the same with Head or Heth, whose name with Comes

attached to it appears as witness in numerous charters of David I.

Head or Heth being the surname of the family,—was in in possession of the

earldom, they remained quiet till 1130, Alexander’s successor David I.

being then on the throne. In that year, an Angus earl of Moray,—either the

individual referred to above, who escaped confiscation by causing his

accomplice Ladman, younger son of Donald Bane, to be put to death, or a

descendant of the same name,—taking advantage of David’s absence at the

English court, broke out into rebellion, and after having obtained